South Street

Essay

Along its east-west course, South Street has been a space where different types of Philadelphians—white and Black, poor and wealthy, parochial and urbane, straight and gay—have met and mingled. From its early days as a theater district, it evolved through various incarnations: from a locus for African American life to a center for immigrant-owned garment shops; from a depopulating backwater slated for destruction to a booming destination for hip consumers. Throughout its rich history, South Street’s diversity and vibrancy have been its main attractions.

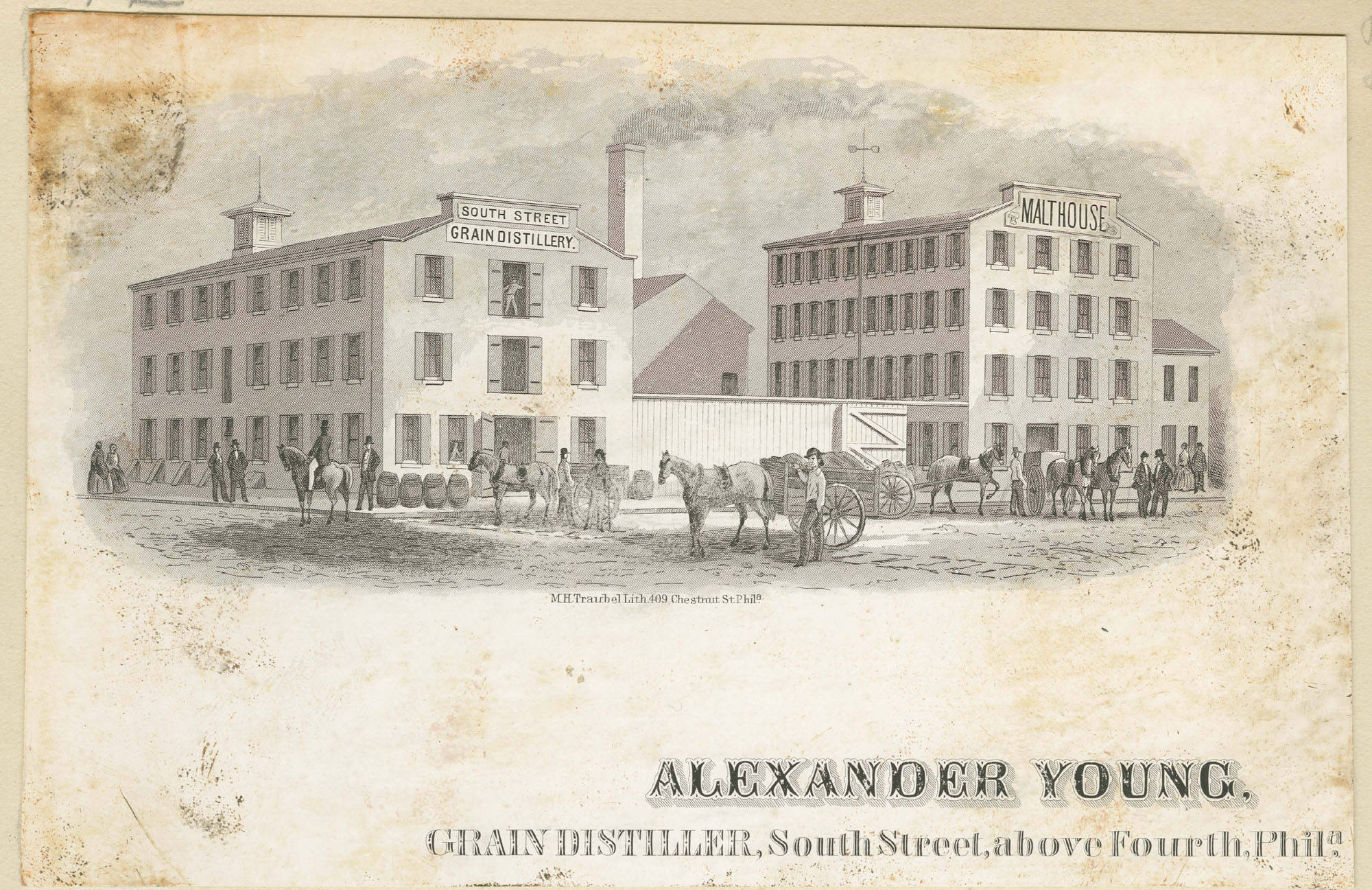

South Street (then known as Cedar Street) formed the original southern boundary of William Penn’s 1682 plan for Philadelphia. In the eighteenth century, it was a liminal space between an increasingly cosmopolitan central city and rural townships to the south. Farmers came to hawk their wares at the New Market, which stood on today’s Headhouse Square at Second and South Streets. Southwark Theatre—Philadelphia’s first—was built on the southern side of the street, since Quaker doctrine forbade live performances within Philadelphia proper. Indeed, over the next three hundred years, South Street would continue to attract those who sought to live beyond the reach of Quaker-influenced city governance.

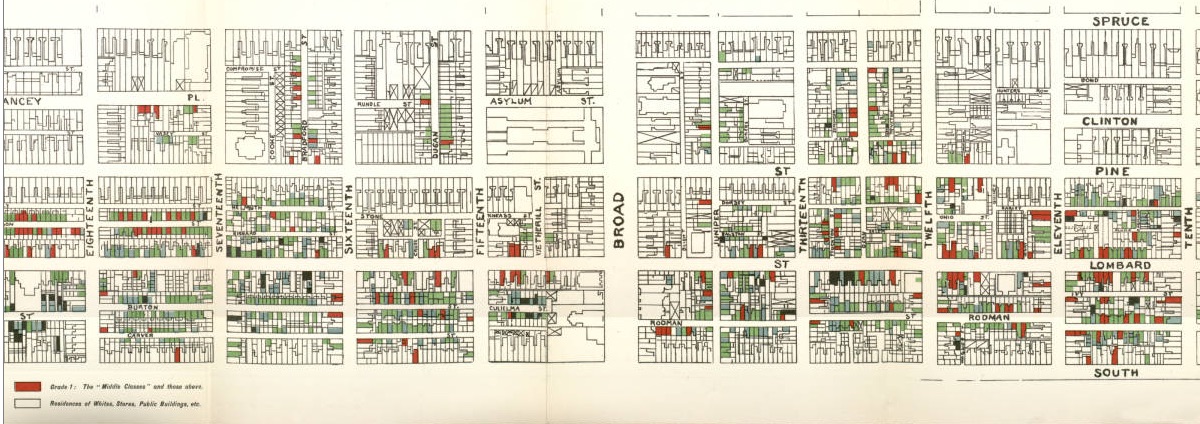

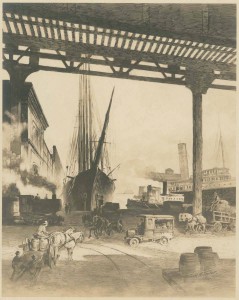

By the early 1800s, South Street was becoming the epicenter of the city’s Black community. Freed slaves clustered near the Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church—the first AME church in America—just north of South Street. After emancipation, Philadelphia’s Black community grew steadily as migrants came north, boosting its numbers from 31,699 in 1870 to 84,459 by 1910. With that growth, Black settlement extended westward to the Schuylkill River along the South Street corridor. Sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) documented life in this densely packed neighborhood in his seminal 1899 study, The Philadelphia Negro. Meanwhile, the western blocks of South Street became a bustling African American shopping and entertainment strip. Black-owned restaurants were especially numerous. Walking down South Street, a recently arrived migrant from North Carolina remembered being met with strange and wonderful odors, the smell of coffee mingling with “spices and the strange, dank odor of the river.”

Wave of European Immigration

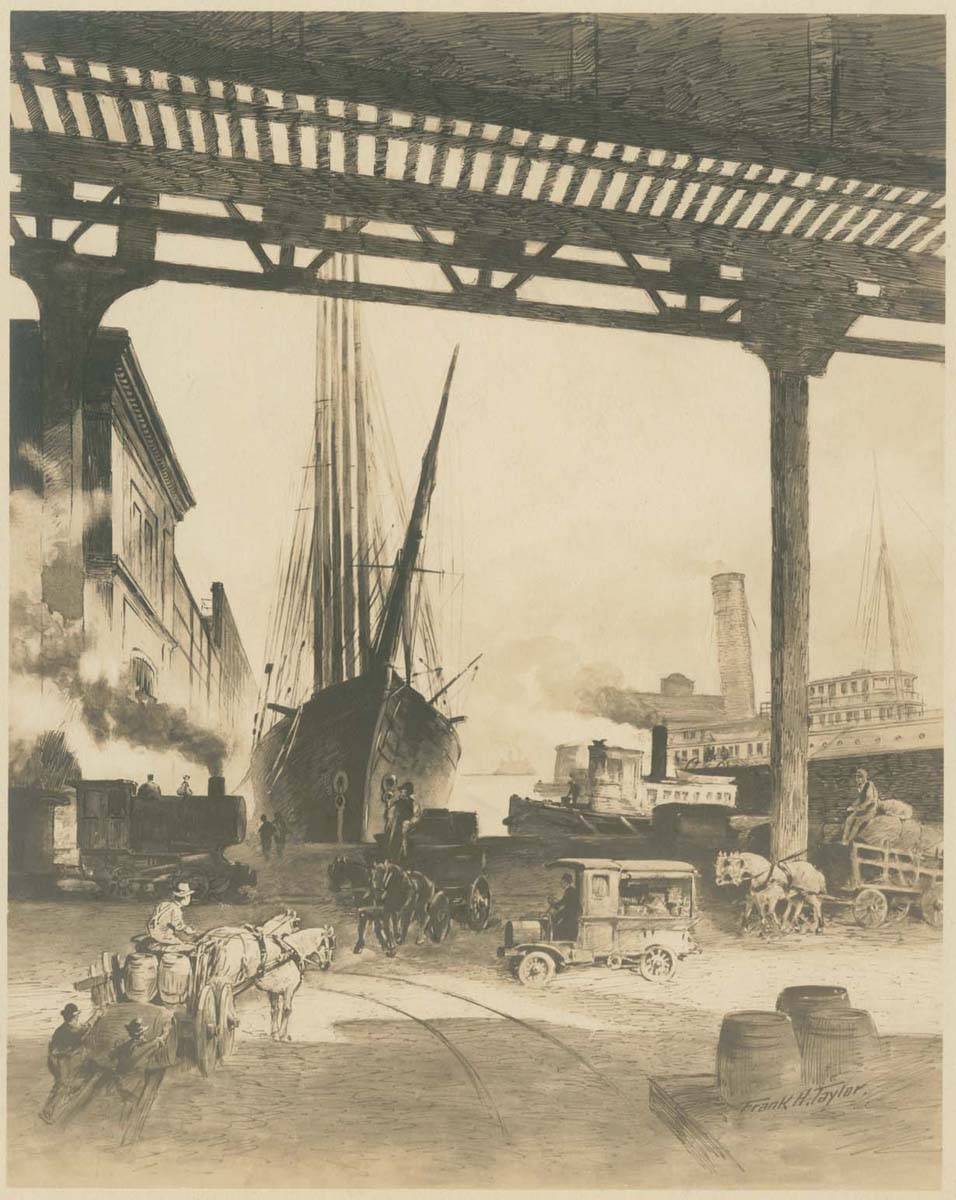

Beginning in the 1830s, African Americans were joined by an increasing number of European immigrants. Droves of Irish came to the area in search of work on the waterfront. In the 1870s, the Pennsylvania Railroad built the Washington Avenue Immigration Station on a pier just south of South Street. Over the next forty-five years, hundreds of thousands of Italians, Poles, and eastern European Jews streamed through the station. Between 1870 and 1910, the number of Philadelphia’s Russian-born Jews rose from fewer than 100 to nearly 91,000. Arrivals listing Italian origins skyrocketed from 500 to 45,000. Many of those immigrants settled just north of the Immigration Station in row houses on or near South Street itself.

By the early twentieth century, South Street had evolved into a commercial corridor with multiple identities. The Shambles, an open-air food market, bustled just north of Second and South Streets. Garment workshops, warehouses, and stores dominated South Street’s eastern stretch, from the Delaware River to Sixth Street, along with adjacent Fabric Row on Fourth Street. These Jewish-owned shops were a less-expensive alternative to Center City’s department stores, and South Street bustled with shoppers looking for bargains. West of Broad Street, the area around South Street was populated by African Americans—some pushed westward by waves of European immigration, others recent migrants from the South. From 1900 to 1920, the number of Blacks living on the blocks around western South Street rose from 9,000 to 12,241. In this area, African American restaurants, churches, and cabarets thrived. In the 1910s, several Black-owned theaters opened on the western stretch of South Street. In the 1920s, Gibson’s Standard Theater hosted famous performers like the vaudeville entertainer Billy Higgins (1888-1937).

In the decades that followed, South Street’s reputation for commerce and entertainment only grew. In 1963, the R&B group The Orlons christened South Street the “hippest street in town,” an homage to the Black hipsters who flocked to South Street’s nightclubs and cruised their cars up and down the strip. Throughout this era, popular novels like William Gardner Smith’s South Street (1954) depicted it as a contact zone—a place where different ethnicities and social classes interacted. South Street was the space where the black community rubbed up against white ethnics and where the working and middle classes met. All of that intermingling translated into excitement. As one of Smith’s characters remarked, “There was life in the air of South Street.”

The Expressway Threat

At the same time, however, South Street was beginning to experience the forces that contributed to its mid-century decline. The biggest blow came with the city’s announcement in the 1950s that it planned to bulldoze South Street and neighboring Bainbridge Street to make way for the eight-lane Crosstown Expressway. Real estate values along South Street plummeted. Vacancy rates soared as businesses and homeowners fled to other commercial districts. After years of traffic studies and funding delays, in 1966 the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation notified South Street’s remaining residents—many of whom were Black and impoverished—that their houses would finally be razed. In response, African American neighborhood leaders George T. Dukes (1931-2008) and Alice Liscomb (1916-2003) mobilized to oppose the planned highway, forming the Citizens Committee to Preserve and Develop the Crosstown Community.

Meanwhile, South Street’s eastern blocks were undergoing a limited revival. In 1964, the avant-garde Theatre of the Living Arts (TLA) opened on the 300 block of South Street. The TLA was an immediate hit. From 1964 to 1969, it sold over 250,000 tickets. The TLA also became a magnet for artists and elements of a burgeoning counterculture as they settled on nearby blocks to give South Street a bohemian air. As galleries and cafes began to spring up around the TLA, South Street was once again becoming a locus of creative energy—an entertainment destination for consumers from all over the region.

In the late 1960s, new residents joined with the existing community to continue fighting the planned Crosstown Expressway. In 1968, this coalition asked the architectural firm of Venturi and Rauch to conduct a study that would demonstrate South Street’s enduring vitality. Denise Scott Brown (b. 1931), the study’s lead author, argued that the city should preserve South Street’s valuable mix of low-cost shops and vernacular architecture. In 1970, a city-hired consultant agreed: The expressway no longer made fiscal or architectural sense. While various planners tried to revive the expressway during the 1970s, it met continued (and ultimately successful) resistance from neighborhood residents.

The Residents Prevail

As the threat of the expressway faded during the 1970s, South Street’s eastern half grew into a lively commercial district. Hip restaurants like the Black Banana and Lickety Split joined feminist bookstores, natural foods stores, and a growing number of galleries. South Street also began to attract many gays and lesbians. In 1973, Giovanni’s Room bookstore opened at 232 South Street. The shop became a center for Philadelphia’s gay community, hosting poetry readings and community meetings.

South Street’s resurgence accelerated in the 1980s and 1990s as newspapers and magazines broadcast the allure of the South Street scene to a broader metropolitan readership. Weekend arts festivals and outdoor concerts drew visitors from all over Greater Philadelphia. The Odunde Festival, a celebration of African and African American culture, was held yearly on the western blocks of South Street. Upscale businesses that catered to increasingly wealthy residents of Bella Vista and Queen Village (neighborhoods to the immediate south of South Street) sprung up. They were joined by edgier storefronts—tattoo parlors, punk-themed record stores, and sex shops—that catered to a youth market. As in decades past, South Street emerged as a heterogeneous commercial corridor, its sidewalks thronged with a diverse range of shoppers.

In the early 2010s, however, the tenuous racial peace that had reigned on South Street was threatened. Hundreds of teenagers, many of them Black, massed on South Street in what city officials called “flash mobs.” There were reports of violence and vandalism; police arrested a handful of youths and enacted a strict curfew. Some media outlets blamed the incidents on social networking, others on poverty and disaffection. Still others claimed that they were simply organized dance parties. Whatever the case, the so-called “flash mobs” demonstrated that racialized fears lurked under South Street’s veneer of diversity. As the western strip of South Street rapidly gentrified in the 2010s—transitioning from majority-Black to majority-white in just a few years—it remained to be seen if the street could retain the peaceable cosmopolitanism that had been its hallmark.

Dylan Gottlieb is a Ph.D. student at Princeton University, where he works on recent American urban history. His latest publication is “ ‘Closer to Heaven’: Race and Diversity in Suburban America,” which was published in the Journal of Urban History. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Odunde Festival draws thousands to a celebration of African culture (WHYY, June 10, 2014)

- Former South St. mecca for artists now hosting dance classes (WHYY, December 1, 2014)

- As summer heat hits Philadelphia, Odunde festival brings South Street to life (WHYY, June 12, 2017)

- 2 dead, 11 injured after shooting on South Street in Philadelphia (6abc via WHYY, June 5, 2022)

Links

- South Street Headhouse District

- South Street West Business Association

- South Street (USHistory.org)

- The South Street Story (WHYY via YouTube)

- American Bandstand: Doing the South Street and More (Bandstand's Best via YouTube

- Hippest Street In Town, Circa 1766 (HiddenCity.org)

- Race and Class in DuBois' Seventh Ward

- Collapse of the South Street Bridge (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Philadelphia's Magic Gardens

- A Royal Loss On South Street (Hidden City Philadelphia, February 24, 2017)