Sports Fans

Essay

In the sports world, Philadelphia fans gained a reputation for enthusiasm as they passionately supported winners and losers, publicly booed, and privately cheered. Many sports fans across the country gained their only understanding of residents of Greater Philadelphia from the region’s sports fans, and out-of-town sportswriters often pointed to select incidents as evidence that Philadelphia fans were out of control. Although a negative image persisted as a powerful force in the media, Philadelphians’ behavior was not measurably worse than that of fans in other cities.

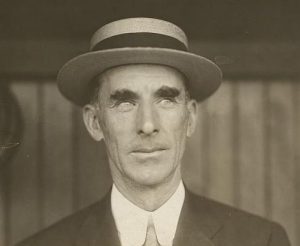

Philadelphia’s passionate sports fans first made their mark in the early twentieth century at Shibe Park, the North Philadelphia home of Major League Baseball’s Philadelphia A’s. Sometimes, A’s manager and team co-owner Connie Mack (1862-1956) took issue with fans. In September 1927, Mack got police to arrest a heckling fan, Harry Donnelly, for disturbing the peace. Mack charged that Donnelly’s heckling had ruined the confidence of many A’s players. Noted hecklers (and brothers) Bull and Eddie Kessler sat on opposite sides of Shibe Park and yelled back and forth at each other and the A’s. In the 1930s, Mack unsuccessfully tried to bribe them with free passes if they would just cheer for the A’s.

One of the best known and most notorious incidents involving Philadelphia fans occurred in 1968 at snowy Franklin Field (the University of Pennsylvania’s football stadium, then also the home of the National Football League’s Eagles). At the end of a season in which the Eagles lost most of their games–but were not bad enough to receive the first pick in the 1969 draft–Eagles management decided to use Santa Claus to entertain the crowd. After the Santa Claus the Eagles hired did not show up, desperate team executives scanned the crowd before finding 20-year-old Frank Olivo (1948-2015), who had come to the game in a Santa suit. Olivo, however, did not look much like Santa Claus; he was thin and wiry. Olivo-as-Santa again disappointed Eagles fans, just as they had been with the team’s play all season, and they reacted as Philadelphia fans might be expected to react when they are disappointed. They booed—a lot. Because there was snow on the ground, they also threw snowballs at Santa Claus. Virtually any time in later years when an issue arose with Philadelphia fans’ behavior, commentators referred back to this incident.

The 700 Level

Eagles fans’ reputation followed them to Veterans Stadium (opened in 1971, closed in 2003), particularly in the stadium’s upper reaches, the 700 level. Fans in that section were often accused of cheering opponents’ injuries but also credited with creating a tremendous home-field advantage for the Eagles. The memory of the 700 level lived on in a popular Philadelphia sports blog, The 700 Level, and Eagles fans at Lincoln Financial Field (opened in 2003) continued to cheer on their team with the same passion as their predecessors.

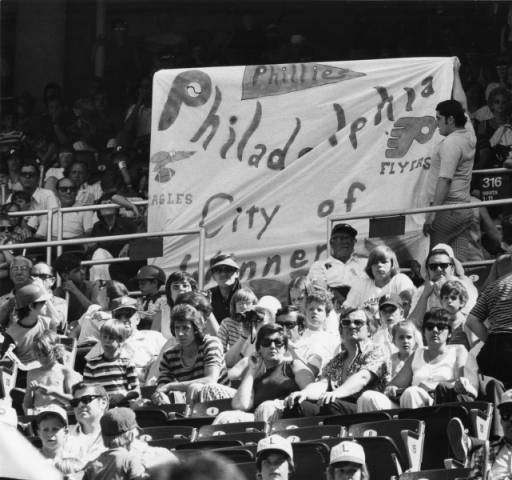

Philadelphia fans invented their own traditions and came to embrace others started by team management. At basketball games in the Big 5 (a long-standing round-robin among five area colleges), fans tossed streamers on the court after the home team’s first successful basket. Big 5 games also became known for sometimes insensitive and explicit “roll outs,” or large signs made by student fans, that often denigrated opposing schools. These traditions, while rare in the twenty-first century, were still occasionally practiced. On a more positive note, in 1969 an executive of the National Hockey League’s Flyers tried to excite the crowd by playing a recording of Kate Smith singing “God Bless America” instead of the Star Spangled Banner. The Flyers won the game and “God Bless America,” sometimes sung live in the Spectrum by Smith herself, became a tradition and a good luck charm that Flyers fans looked forward to. Baseball fans also embraced and enthusiastically joined in the antics of the Phillie Phanatic, a team-created mascot introduced in 1978, including his habit of putting a “hex” on the opposing pitcher late in the game in an attempt to aid the Phillies.

When Philadelphia’s major professional teams won league championships (including the Flyers in 1974 and 1975, the Phillies in 1980 and 2008, and the National Basketball Association’s 76ers in 1983), the city celebrated with parades down Broad Street from City Hall to the Sports Complex, home of Philadelphia’s four major professional sports teams. Although a common way to celebrate championships, the fans lining the parade route give such revelry a uniquely Philadelphia flavor. From the corporate offices of Center City through the multiethnic and multiracial neighborhoods of South Philadelphia, a wide swath of residents of Greater Philadelphia came out to support their teams. In 1980, one of those residents was Jamie Moyer (b. 1962), a student at Souderton High School. Twenty-eight years later, Moyer again attended a victory parade, but this time as a member of the World Champion Phillies. Moyer was the rare person to experience both sides of such a monumental event in Philadelphia sports history.

A Charitable Side, Too

Despite their harsh reputations, Philadelphia fans have embraced the less fortunate among them. For example, Harry “Yo-Yo” Shifren (1908-79) was often homeless and unable to hold a steady job, but he frequented Big 5 basketball and Phillies games. Unable to afford admission, he successfully solicited tickets from fans and members of the media. At Big 5 games, Shifren made his presence known by dancing on the court and by comically missing underhanded free throws at half time. He was such an important element of the experience at Phillies games that the team gave him a lifetime pass in 1974. When Shifren died in poverty, the Phillies paid for his funeral.

Two incidents in April 2016 highlighted the continued passionate support of Philadelphia fans for their teams. Despite the antipathy between alumni and supporters of Big 5 schools, many Philadelphians temporarily discarded their partisanship and joined together to cheer on Villanova University in the National Collegiate Athletic Association men’s basketball tournament. Later, thousands of Philadelphians gathered at City Hall to celebrate the victorious Wildcats. In contrast, however, one of the Flyers’ playoff games that month was marred by displeased fans throwing memorial bracelets onto the ice in response to poor play by the home team. The bracelets had been given out in honor of recently deceased Ed Snider (1933-2016), team founder and president. This incident, casting a negative light, nonetheless demonstrated how much Philadelphia fans cared about their teams.

While not always directed positively, Philadelphia sports fans’ passion has been undeniable. Many American sports fans, and fans all over the world, get their only impression of the people of Philadelphia from passionate Philadelphia sports fans. Understanding the history of those sports fans sheds light on how non-Philadelphians think about residents of the Greater Philadelphia area.

Seth S. Tannenbaum is a lifelong Philadelphian and a doctoral candidate in American history at Temple University. His research has appeared in the Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and American Culture, 2013-2014. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University