Streetcar Suburbs

Essay

Beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century, Philadelphia’s growing streetcar network facilitated the movement of upper and middle class Philadelphians to residential districts outside of the urban core. New streetcar-centric suburban developments combined the allure of pastoral living with fast access to work and commerce in central Philadelphia. In this way, streetcar suburbs represented a paradox: While their chief attraction was their seemingly natural setting, their existence depended on the Philadelphia’s industrialization, which expanded the ranks of the city’s middle class while also making central Philadelphia a less desirable place to live.

Previously, most of Philadelphia’s elites had lived in the center of the city, with poorer residents inhabiting the periphery. The mid-nineteenth century influx of working-class immigrants, however, forced well-heeled Philadelphians to rethink that arrangement. The arrival of Irish and German immigrants led to overcrowding, crime, disease, and social unrest; the city was wracked by anti-Catholic riots during the 1840s. For the middle classes, moving to the city’s fringes provided a buffer from such disorder—a comfortable distance from what they believed were undesirable nonnative populations.

The era of industrialization also changed the middle classes’ perception of the city. As the industrializing city grew increasingly packed and polluted, there arose a newfound appreciation for picturesque natural landscapes. For those who worked in the commercial heart of the city, the rural fringe promised a refuge—a private residential sphere for the bourgeois family. In the 1840s, influential landscape architect and author Andrew Jackson Downing (1815-52) popularized the connection between country houses and moral behavior among his middle-class readership. While elites had long built manors in Philadelphia’s rural hinterland, after the Civil War the middle class—factory managers and businessmen who worked in finance or retail—now aspired to spacious pastoral housing of their own.

Building Middle-Class Havens

That said, the suburban lifestyle would have been impossible without the advent of an efficient means to transport the middle class to and from the central city. While horse-drawn omnibuses operated from the 1830s, they were slow and inefficient. At mid-century, Philadelphia remained a “walking city.” In 1850, the average worker lived within six-tenths of a mile of his or her job. By the late 1850s, however, the advent of faster horse-powered streetcars running on rails greatly increased the distance commuters were able to travel. Too expensive for the working classes to afford, streetcar ridership was restricted to the growing ranks of middle-class commuters. As they extended their tendrils outward, streetcar lines made possible the creation of class-segregated residential districts at the urban fringe.

In the 1850s, speculators began to erect suburban-style housing for middle-class buyers in West Philadelphia—which, as of 1854, had been consolidated into Philadelphia proper. Early developers sought to emulate the style of the elite country houses that already dotted the area. Hamilton Terrace, a row of Gothic Revival and Italianate twin houses on South Forty-First Street between Baltimore and Chester Avenues, was one of the first developments. Architect Samuel Sloan (1815-84) gave Hamilton Terrace features that evoked upper-class country homes: front and rear lawns, porches, and ample tree cover. Sloan also designed nearby Woodland Terrace, a development of semidetached houses built in 1861. Woodland Terrace’s charter protected its character as a residential refuge, mandating that “no slaughterhouse, skin dressing house or engine house, blacksmith shop or carpenter shop, glue, soap, candle or starch manufactory or any other offensive occupation be erected” in the area.

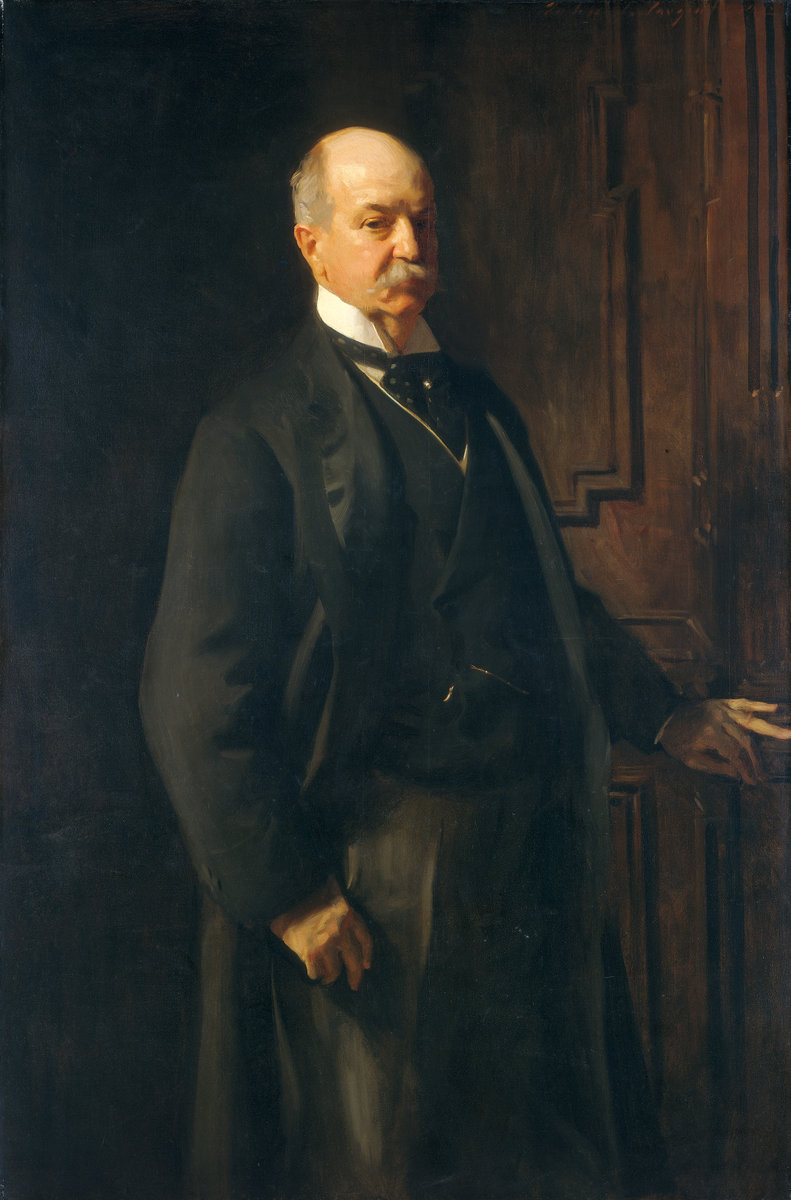

Development accelerated as streetcar operators joined in the speculative real estate market. In the 1880s, investors Peter A. B. Widener (1834-1915) and William Elkins (1832-1903) joined forces to consolidate control over the city’s street railway franchises. Their Philadelphia Traction Company ran new lines along the path of their property holdings, enabling them to capitalize by building new suburban-style developments. In the 1890s, they laid trolley lines on Springfield and Chester Avenues, sparking new construction in the Squirrel Hill and Kingsessing neighborhoods in Southwest Philadelphia.

Country-House Amenities in the City

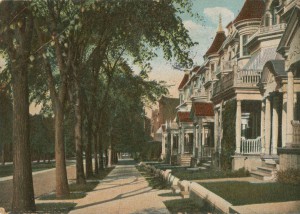

West Philadelphia grew denser as builders synthesized the country-house style with the density of urban row houses. While they retained their front porches and lawns, they began to build attached rows of Queen Anne and Colonial Revival-style houses in neighborhoods like Cedar Park. Developers advertised their communities’ urban-style amenities—sewers, gas lines, and, later, electricity—along with their pastoral setting. As housing became denser and more affordable, the population of West Philadelphia swelled from under 24,000 in 1860 to about 200,000 in 1910. By the 1890s, development pushed past Forty-Second Street. Commercial corridors sprang up to serve these farther-flung suburban areas. Shops soon dotted stretches of Lancaster Avenue, Fifty-Second, and Sixtieth Streets in West Philadelphia. Streetcar ridership flourished as more people moved farther from the city center: 99 million passengers rode the Philadelphia streetcars annually by 1880.

As the areas around Philadelphia and Camden developed, streetcar-led construction extended farther from their city centers. Streetcars linked growing communities in Delaware County—Lansdowne, Media, Collingdale, Glenolden, and Sharon Hill—to the urban streetcar network via a hub in Darby. Montgomery County’s expanding network of suburban streetcar lines converged in Norristown, northwest of Philadelphia along the Schuylkill River. In southern New Jersey, streetcar routes radiated out from Camden’s industrializing core. By the early 1900s, new lines eased travel between Camden and the nearby suburbs of Merchantville, Collingswood, and Haddonfield, complementing their existing railroad links to Philadelphia. Well-heeled buyers moved out to suburban Chestnut Hill in Philadelphia’s northwest, commuting downtown via the Germantown Avenue streetcar (and multiple railroad lines). To ensure that Chestnut Hill would remain uniformly white and middle class, area developers employed restrictive covenants that barred industrial or commercial uses, along with Black and Jewish residents. Residents included the renowned father of scientific management, Frederick W. Taylor (1856-1915), who conducted his time-efficiency studies at North Philadelphia’s Midvale Steel plant.

At the start of the twentieth century, non-elites began to move out to suburban districts within (and eventually outside) of city limits. Electrification of the city’s streetcars in 1892 and completion of the Market Street Elevated line in 1907 lowered transit costs, making it possible for some workers and upwardly-mobile immigrants to afford a daily commute. In West Philadelphia, the demand for housing led to the construction of four- and five-story apartment buildings in areas formerly devoted to single-family homes; it also sparked development in the outlying neighborhoods of Wynnewood and Overbrook. In North Philadelphia, developers built homes in Olney and Oak Lane to accommodate the growing ranks of successful Germans and Irish (and later Jews) who sought refuge from central Philadelphia’s industrial neighborhoods. Across the river in southern New Jersey, streetcar electrification lowered the costs of commuting into Camden, allowing shopkeepers and clerical works to move to nearby towns. Developers’ advertisements enticed former immigrants to move to neighborhoods like Strawberry Mansion, an enclave on the edge of Fairmount Park. One broker’s 1913 Yiddish-language ad for the neighborhood promised residents “fresh air” and a “beautiful country landscape”—the same sort of pastoral features that had originally drawn the middle class to West Philadelphia’s first streetcar suburbs.

The Automobile Affects Development

With the advent of the automobile after World War I, suburban construction no longer needed to follow transit routes. In West Philadelphia, developers began to target areas not serviced by streetcar lines. The Garden Court district, built during the 1920s, was among the first to incorporate rear garages on the homes’ basement level. In the following decades—particularly in the years after World War II—auto-centric suburban development exploded in areas outside of Philadelphia’s city limits.

Government policies that helped to underwrite automobile suburbs also accelerated the transformation of older streetcar suburbs into lower-class neighborhoods. Middle-class residents of inner suburbs took advantage of favorable government-backed mortgages to buy new houses outside the city. Meanwhile, African Americans migrating to Philadelphia were subject to residential restrictions that pushed them into neighborhoods—Mantua, Parkside, Strawberry Mansion—that the white middle class was abandoning. Landlords took advantage of the situation by dividing historic single-family homes into multiple apartments. Owners failed to invest in upkeep, and many early suburban-style houses began to deteriorate. Federal agencies like the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation hastened disinvestment when they deemed aging and racially-transitioning streetcar suburbs unworthy of mortgage financing.

In the final decades of the twentieth century, however, streetcar suburbs began to experience a limited resurgence. New immigrants flocked to areas like Cedar Park and Upper Darby for their affordable housing and access to jobs downtown. Middle-class returnees were also attracted by the supply of inexpensive historic houses. Streetcar suburbs offered amenities that automobile suburbs lacked: density, walkability, defined commercial corridors, and, most importantly, easy access to public transit. By the beginning of the twenty-first century, middle-class residents filled many of Philadelphia’s earliest streetcar suburbs, and the most architecturally distinctive area of West Philadelphia received designation as a historic district. Once again, streetcar suburbs came to embody the ideal intersection of urban convenience and bucolic refuge.

Dylan Gottlieb is a Ph.D. candidate at Princeton University, where he works on recent American urban history. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Is Chestnut Hill a hot place for the arts? (WHYY, May 20, 2012)

- Clinic in Olney expands with 'wraparound service' to accommodate newly insured (WHYY, September 13, 2013)

- Selling gentrification to neighbors of the old West Philadelphia High School building (WHYY, June 19, 2014)

- New stores line Kings Highway in Haddonfield (WHYY, January 23, 2015)

- At Norristown theater, 'In the Blood' explores world of the homeless (WHYY, May 5, 2015)

Links

- Back From The Brink In Kingsessing (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Widener Mansion (PhillyHistory Blog)

- West Philadelphia Community History Center (University of Pennsylvania)

- West Philadelphia: A Suburb in a City (PhillyHistory Blog)

- New ‘renaissance school' hailed as big step forward for Camden kids (NJSpotlight.com)