Subways and Elevated Lines

By John Hepp | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Philadelphia’s subway and elevated network consists of four lines that connect with other transportation options to serve much of the region. Although the network is relatively simple compared with systems in other cities, its history is complex. It took over eight decades to plan and to build, and its construction required a variety of public-private partnerships. More recently, public agencies have worked to update and to modernize the network.

Agitation for a rapid transit system for Philadelphia began shortly after the Centennial Exhibition of 1876, although a contemporary history of the fair proclaimed Philadelphia’s horse-drawn street railways constituted “the best system of street transportation in the Union.” In the 1880s and 1890s, those who wanted better transit often allied themselves with other boosters who sought a “New Philadelphia,” and both groups agreed that this should include separating home from work for more Philadelphians by developing rapid transit. Philadelphia and the region experimented with a variety of transportation alternatives at this time, including new steam railway stations in Center City approached by elevated tracks, cable and steam-powered streetcars, and eventually electric trolleys. The extensive electric trolley network provided the city with effective short distance transportation, and the steam railroad commuter trains gave the region expensive but high-speed, longer distance service.

Despite all these changes, Philadelphia still faced a rapid transit crisis in 1900. The city was growing fast and lacked adequate high-speed, inexpensive mass transportation to accommodate the growing demands for commuting, shopping, and enjoying parks and other places of recreation. Looking at other cities, Philadelphians could see two possible solutions. London had pioneered the steam-powered subway in 1862 and opened a more practical electrically powered line in 1890. New York City offered the competing vision: it had used steam-powered elevated trains since 1871. Subways were more expensive to construct but less disruptive on the physical environment after they were built while the cheaper elevated railways were both unsightly and noisy.

Rapid Transit Arrives

After decades of debate, in 1901 Pennsylvania approved a rapid transit ordinance for Philadelphia that allowed for both subway and elevated lines. Franchises were quickly granted, but in the best tradition of machine politics (in this case it was the Matthew Quay (1833-1904) machine in Harrisburg), this rapid movement was more about political retribution than urban transit. The William L. Elkins (1832-1903)-Peter A. B. Widener (1834-1915) syndicate, owners of the near-monopoly trolley company in Philadelphia, had not supported Quay’s candidacy in the previous election. The franchises went to political allies of Quay, who eventually transferred them all (at high cost) to the Elkins-Widener group that then raced to complete the lines within five years, as required by the franchises.

Philadelphia Rapid Transit (the final name of the Elkins-Widener property in the city and commonly known as the PRT) promptly started construction on the Market Street line but had trouble raising money because of its large debt from previous transit projects. Eventually in 1907, the PRT and the city negotiated an agreement that gave the city limited oversight of the PRT in exchange for regulatory and subway route changes (including transferring the franchises for the remaining lines to the city). The PRT first began operating the subway-surface cars between Fifteenth Street and the Schuylkill River in 1905. Regular subway-elevated service began on March 4, 1907, between the Fifteenth Street and Sixty-Ninth Street stations (although not all stations on the elevated portion of the route west of the Schuylkill were open initially). This subway service was extended to Second Street station on August 3, 1908, and a little over a month later the elevated loop that served the ferry termini on Delaware Avenue opened.

This initial line served four important purposes and was a model for future transit development. It dramatically reduced trolley congestion on the streets of Center City. It also allowed the department stores, theatres, and offices of Center City to reach a larger market. It encouraged the residential development of West Philadelphia beyond about Fortieth Street and connected with crosstown trolley lines throughout West Philadelphia, opening even more land for development. Finally, it helped establish patterns in suburban development by turning Upper Darby (where the Market Street line interchanged with suburban transportation lines) into a key commercial and transit node.

After the completion of the Market Street line, the city took the lead role in rapid transit planning and funding in the region until the 1960s. It established a Bureau of City Transit in 1912 that created a master transportation plan for Philadelphia. Although most of the proposed lines were never built, this report provided the blueprint for twentieth-century developments.

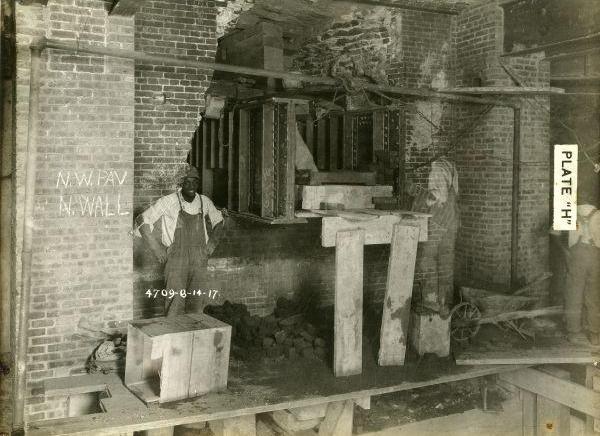

El Extends to Frankford

The city first built an elevated extension of the Market Street line to Frankford in Northeast Philadelphia and began construction at the same time on the City Hall station of the proposed Broad Street subway and a Center City subway loop. In 1917, although work continued on the Frankford elevated, it halted on the other lines. The city also purchased the cars necessary to operate the extension and leased both the cars and the line to the PRT, which began operation in 1922. The final two stations in Frankford became transportation hubs that allowed for the development of Northeast Philadelphia. The city next started work on the Broad Street subway. The PRT opened this line between Olney and City Hall in 1928 and two years later extended it to South Street. A branch under Ridge Avenue to Eighth and Market streets opened in 1932.

During the Great Depression subway construction slowed and the only contraction in the system’s history occurred. Although the tunnels for the Broad Street line to Snyder Avenue in South Philadelphia were completed in 1933, the line did not open until 1938 because of funding issues. The tunnels for the Locust Street line, started in 1917, were completed by 1931, but it did not open until after the war. The Delaware River Joint Commission (now the DRPA) opened a line over what is now the Benjamin Franklin Bridge between Eighth and Market streets in Philadelphia and Broadway in Camden in 1936, operated by the PRT. In 1939, the PRT abandoned the elevated structure on Delaware Avenue due to declining ridership on the ferries because of the bridge.

Since World War II, only five modifications to this system were completed. In 1953, the long-delayed Locust Street subway began operation as part of the Broad Street and Camden systems. The Market Street subway was extended westward under the Schuylkill River to a new portal after the Fortieth Street station, and the corresponding section of the elevated was abandoned in 1955. The next year, the Broad Street line was extended one stop northward to a park and ride facility at Fern Rock. The most significant change to the system occurred in the 1960s when the underutilized Locust Street line was transferred to the DRPA, which combined it with the Camden line and extended it to Lindenwold, New Jersey (on the route of a lightly used railroad commuter line serving Camden). This Port Authority Transit Corporation (PATCO) line opened in 1969 and featured air-conditioned and computer-operated trains. It helped to further economic development in South Jersey and to maintain Eighth and Market Streets (where it connects with the Market-Frankford subway) as a major transportation and shopping hub in the city. Most of its suburban stations were provided with large parking lots and local bus connections. Finally, in 1973, the Broad Street line was extended southward to Pattison Avenue (now AT&T station) to serve the sports complex.

John Hepp is associate professor of history at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where he teaches American urban and cultural history with an emphasis on the period 1800 to 1940. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- SEPTA considers restoring late-night subway service (WHYY, February 21, 2014)

- SEPTA budget draws praise, no boos, at Philly public hearing (WHYY, April 22, 2014)

- Broad Street subway service for night owls begins (WHYY, June 13, 2014)

- SEPTA transit police testing wearable camera technology (WHYY, July 16, 2014)

- SEPTA extending trial of late night weekend service on El and Broad Street Line (WHYY, August 6, 2014)

- Local man wins protections for iconic cast-iron subway entrances (PlanPhilly via WHYY, March 13, 2019)