Vietnam War

Essay

The Vietnam War, like the Great War, World War II, and Korean War before it, had a significant impact on the Philadelphia region. During the height of open American involvement in the war from 1965 to 1968, thousands from the area were drafted or volunteered for the armed forces, and hundreds lost their lives. Other citizens participated in antiwar or peace protests. While the war created employment in defense industries, it limited economic opportunity in other ways, especially in the postwar period. Among the most lasting of the war’s impacts, the region gained a more diverse population from an influx of political and economic migrants from war-torn countries in Southeast Asia.

In the early 1960s, few people were fully informed about the events that had transpired in Vietnam since the end of World War II. The United States had been involved in the region for decades, initially supporting France with billions of dollars of aid against anticolonial Vietnamese nationals. After the departure of the French in the mid-1950s, the United States remained in the region and supported anti-communist forces there as part of the larger Cold War against the Soviet Union, lending support to the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) while opposing the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam).

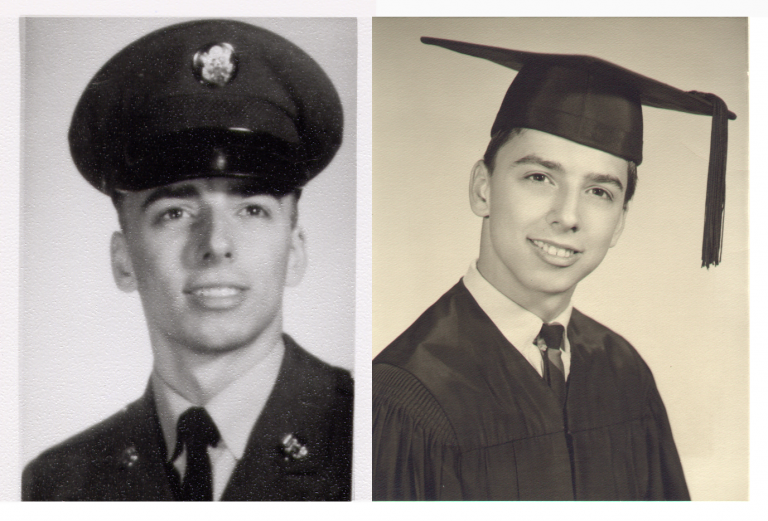

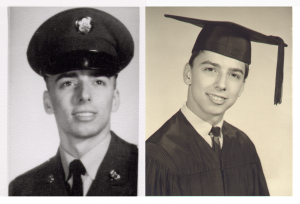

Young men from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware became drawn into the Vietnam War in large numbers between 1962 and 1968 as American troop levels in South Vietnam escalated from 10,000 to nearly 550,000, the vast majority added after the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident. By the end of the war in 1975, when the North Vietnamese captured Saigon and the United States withdrew its last contingent of regular military forces, more than 3,100 Pennsylvanians had been killed as a result of the conflict. Of these, 646 (20 percent of all the Keystone State’s war dead) came from the city of Philadelphia alone. Philadelphia’s Edison High School lost sixty-six alumni, more than any other high school in the United States. The city of Camden and Camden County accounted for nearly 6 percent of New Jersey’s nearly 1,500 killed, while Wilmington and New Castle County accounted for 68 percent of 122 men from Delaware who perished.

Anti-War Activism

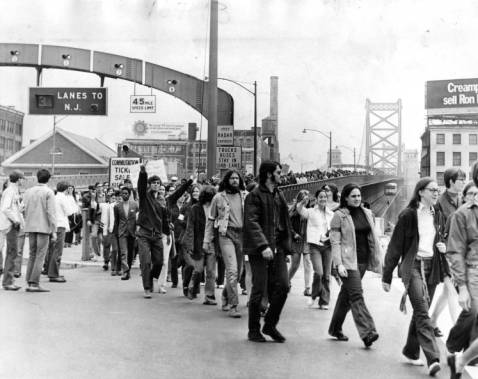

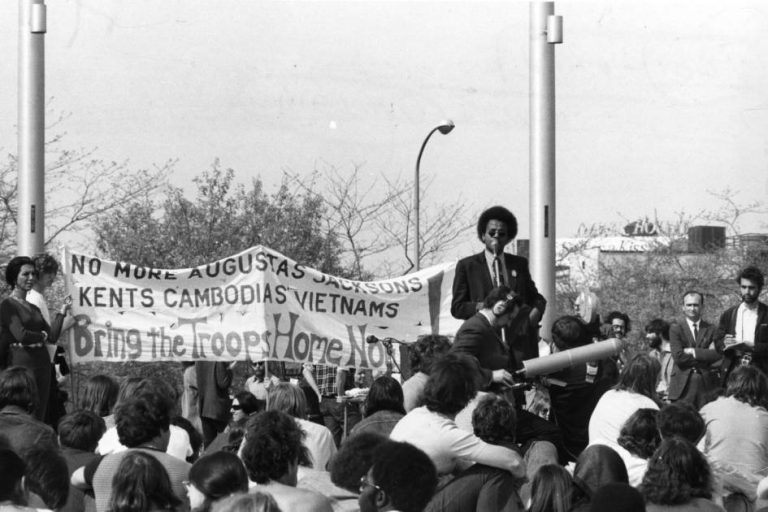

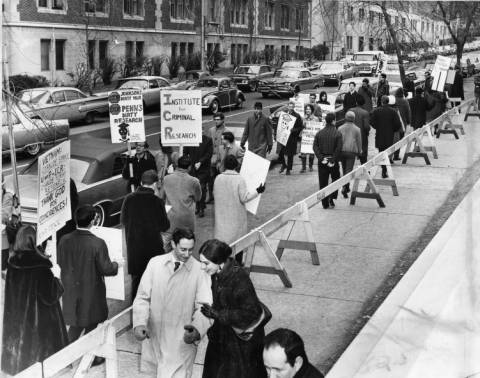

The enormous manpower needs and the increased “credibility gap” between the federal government’s rationale for the war versus the realities conveyed through television and soldiers’ accounts led to the development of what one scholar has called the “largest and most effective antiwar movement in American history.” While not limited to college students, anti-war activism in the Philadelphia region drew strength from increased enrollments on many of the region’s campuses, due in part to the awarding of educational deferments for the draft. In 1966, students and faculty at the Quaker-founded colleges of Haverford, Bryn Mawr, and Swarthmore Colleges went on an extended hunger strike to protest American involvement in the conflict, an action eventually joined by students at Friends Select High School. By 1967, mass demonstrations, teach-ins, petitions, and civil disobedience spread beyond locations and groups traditionally associated with pacifism, extending to Temple University, the University of Pennsylvania, and other campuses. As a result of nearly two years of campus protests and debates, Penn’s Board of Trustees overwhelmingly decided to cancel its chemical and biological warfare contracts with the Pentagon.

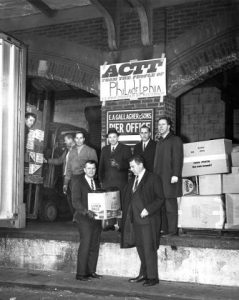

As in other metropolitan areas across the country, most people were not directly involved in fighting the war, but they experienced its impact and divisiveness nonetheless. Debates about the Vietnam War and American involvement took many forms on college campuses, at federal facilities, and in public spaces. Philadelphians demonstrated in support of the war as well as against it. The Liberty Bell and Independence Hall, symbols of American democracy, became contested sites for demonstrations by those who supported the war as a crucial element of the Cold War against Communism as well as those who believed the war immoral or simply a waste of taxpayer money. In this heated political climate, acts of open defiance toward the American government occurred, such as the “Camden 28” raid of one of the city’s draft boards and the theft of classified documents from an FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania.

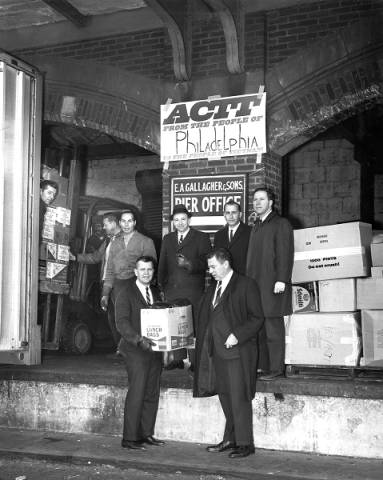

When young men were drafted or enlisted, their absence from the workforce opened opportunities for others. Philadelphians benefited by working in defense industries such as local shipyards, arsenals, and private companies that supplied material and weapons to the military. In 1968, economists estimated that without the Vietnam War, local employment in federal government agencies related to the war effort would have dropped 10.2 percent, amounting to thousands of people, and total federal expenditures in the Philadelphia region would have dropped 42.3 percent, amounting to nearly $2.5 billion.

After the war, the region and the nation as a whole experienced starkly negative economic impacts. Because the Vietnam War and the Great Society domestic programs of President Lyndon B. Johnson (1908-73) had been financed simultaneously without any significant increases in taxes, the ensuing effects of runaway double-digit inflation and mounting federal debt ravaged the economy. Although veterans had opportunities for education through the G.I. Bill, the poor state of the American economy compounded with declining industry in the region meant that many would not have the same economic opportunities as previous generations of veterans.

Postwar Impact

In addition to the challenges of a deindustrializing economy, the smooth reintegration of Vietnam veterans was further complicated by postwar health and addiction issues. These included the debilitating effects of exposure to the toxic herbicide “Agent Orange” (the Veterans Administration presumes that anyone who served in Vietnam between January 9, 1962, and May 7, 1975, was exposed and therefore eligible for benefits), drug abuse, homelessness, and post-traumatic stress disorder.

America’s longest war in the twentieth century also led to one of the most dramatic and visible demographic changes in the region’s history. Although not always welcomed—a study by the Philadelphia Commission on Human Relations revealed that the new arrivals were disproportionately victims of interracial violence in the late 1980s—a surge in refugees in the aftermath of the Vietnam War led significant numbers of Southeast Asian migrants to resettle in the region. This influx, combined with post-1965 American immigration policy that emphasized family reunification and encouraged chain migration, made Philadelphia home to one of the largest Vietnamese communities and the second-largest Cambodian community in the United States.

By the arrival of the twenty-first century, the Vietnamese were the largest foreign-born population in Philadelphia, numbering nearly 12,000. South Philadelphia and Elmwood, neighborhoods known for migrants from European countries in previous times, became spaces where these newcomers resided and congregated. Vietnamese refugees, especially those who could speak Chinese, initially frequented Chinatown and proved a boon to shop owners there, but by the twenty-first century they had carved out a neighborhood that became colloquially known as “Little Saigon” in South Philadelphia. By 2015, the combined Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington Metropolitan Statistical Area had a population of 34,507 Vietnamese, with the outskirts of the city of Philadelphia and nearby towns like Pennsauken, Egg Harbor, and Atlantic City home to their highest concentrations; Camden County had become home to 4,260 Vietnamese, the largest number in any county of New Jersey. The influx of these new Americans from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos introduced a polyglot of cultures, foodways, and traditions into the already diverse region, reinvigorating the region just as previous generations of immigrants before them.

For decades afterward, the impact of the Vietnam War could be seen, and remembered, across the region. Penn’s Landing became home to the largest memorial for Philadelphia’s war dead, but equally poignant plaques and spaces honored individuals who served and perished. The statewide New Jersey Vietnam Veterans’ Memorial was erected in Holmdel, New Jersey, for the same purposes. Veterans Memorial Park in downtown Dover, Delaware, added several Vietnam memorials in addition to those for servicemen lost in other conflicts. Edison High School built a memorial to its alumni, just as many other smaller organizations did after direct American military involvement ceased. Nearly a half century after the end of the Vietnam War, the legacy of the conflict could also be seen in the faces of the Southeast Asian migrants and their children who made the city of Philadelphia and its environs their home.

Nicholas Trajano Molnar is Assistant Professor of History at the Community College of Philadelphia and author of American Mestizos, the Philippines, and the Malleability of Race, 1898-1961 (University of Missouri Press, 2017). Previously, he served as Assistant Director of the Rutgers Oral History Archives. Trajano Molnar serves as the Digital Humanities Officer of the Immigration and Ethnic History Society and coordinates the “Philly Stories” Student Oral History Archive. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Bucks County Vietnam vet reaches for the U.S. Senate (WHYY, April 16, 2012)

- Hundreds honor troops at N.J. Vietnam Veterans Memorial (WHYY, November 11, 2013)

- Philly's only Vietnam-era Medal of Honor recipient still touching lives 45 years after death (NewsWorks, February 12, 2013

- 45 years later, Delaware family accepts personal belongings of U.S. soldier lost in Vietnam (NewsWorks, May 30, 2013)

- Vietnam War vets build Bell 'Huey' Helicopter for Philly exhibit (WHYY, May 31, 2013)

- Veterans, family gather for ceremony renaming VA Center after West Oak Lane war hero (WHYY, May 4, 2015)

- Sen. Carper reflects on trip to Vietnam with Pres. Obama (WHYY, May 27, 2016)

Links

- Philadelphia Vietnam Veterans Memorial at Penn's Landing

- Charles "Chicky" Gibelterra Jr. (Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund)

- Asian Immigrant Populations in Philadelphia (GlobalPhiladelphia.org)

- In South Philly, Subtly Staking Territory (Philadelphia's Vietnamese Population) (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- “Even Princeton”: Vietnam and a Culture of Student Activism, 1967-1972 (Princeton University)