Face Shield

By Jeffrey Ray

Essay

Plexiglas face shield with embedded bullet, c. 1960s. (Philadelphia History Museum Collection, transfer from Fire Arms Identification Unit, Philadelphia Police Department, 1991, Photograph by Sara Hawken)

Plexiglas face shield with embedded bullet, c. 1960s. (Philadelphia History Museum Collection, transfer from Fire Arms Identification Unit, Philadelphia Police Department, 1991, Photograph by Sara Hawken)

This face shield for a police helmet is made of Plexiglas. Whenever it has been on exhibit at the Philadelphia History Museum, it has attracted the attention of visitors, especially boys. Especially fascinating is the bullet that can be seen lodged in the center of the shield. Fired from a gun at close range in a test for the Philadelphia Police Department, the bullet stopped just millimeters from breaking through the inside of the mask. The bullet hit the Plexiglas, which is just under a half of an inch thick, started to melt the plastic, and then expanded and began to break apart. Other, thinner versions of the mask were tested, and they either shattered on impact or managed to slow bullets that melted the Plexi.

This mask came to the Philadelphia History Museum in 1991 from the Firearms Identification Unit of the Philadelphia Police Department, but it is also part of the region’s history of industrial innovation. Plexiglas is a trade or brand name for a clear acrylic plastic developed in the 1930s by the Rohm and Haas Company, based in Philadelphia. Described by company president Otto Rohm (1876-1939) as “organic glass,” Plexiglas is thermoplastic, meaning that it can be heated and then molded or formed into many shapes. It can be worked using readily available tools such as drills and saws. Plexiglas, along with other acrylic plastics such as Lucite and Perspex, had a great impact on everyday life and specialized manufacturing during the second half of the twentieth century

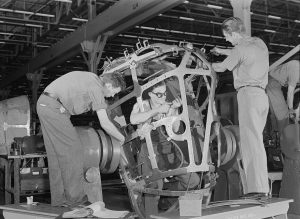

Rohm and Haas began developing its clear acrylic plastics in the early 1930s at the company’s facilities in Darmstadt, Germany, and in Bristol, Pennsylvania, just north of Philadelphia. Production of sheets of Plexiglas began in Darmstadt in 1934 and at the Bristol facility in 1936. While it is one thing to develop a new material, it is quite another find uses for it. Early uses for Plexiglas were in spectacles, display cases, and lighting fixtures. Plexiglas got a big boost at the 1939 New York World’s Fair, where many products using Plexiglas were displayed. The General Motors pavilion at the fair had an illuminated sign made of Plexiglas and inside a Pontiac with a Plexiglas body allowed visitors to see the automobile’s inner workings.

By far the biggest market for Plexiglas was with the military. In 1938 Rohm and Haas sold almost half a million dollars’ worth of Plexiglas, 80 percent of it for use in military aircraft. Sales soared after the start of World War II, as the military used Plexiglas in bombardier and gunner enclosures, gunner turrets, in side windows and in the tail assemblies of thousands of planes. By 1944, Rohm and Haas sales of Plexiglas reached $22 million, virtually all of it from the military.

After the Second World War, sales of Plexiglas fell drastically (in 1947, its largest market came from manufacturers in need of clear covers for juke boxes). The company returned to promoting the pre-war uses of Plexiglas in spectacles, light fixtures, and architecture. A major breakthrough for the future came when Dr. Stanton Kelton Jr. (1915-93), a member of the Plexiglas production laboratory, found a dye for Plexiglas molding powder that would not fade with exposure to light. Plexiglas molding powder became the industry standard in the production of tail lights for American automobiles.

Colored Plexiglas also spelled the end of neon signs and altered the urban landscape in the United States and around the world. Before World War II, a sign could be illuminated in one of two ways: by shining a light directly on it or by using neon-filled glass tubes to outline or trace design elements. With the advent of colored sheets of Plexiglas, it became possible to make signs using layers of the colored plastic, and they could be lit internally. Sales of Plexiglas for signs took off in 1948 after Underwriters Laboratories (an independent testing company that cities and insurance companies rely on) developed standards for the use of Plexiglas in signs.

The object pictured on this page represents an experiment with Plexiglas that did not quite work out. Dating from the late 1960s, when the Philadelphia Police Department sought greater protection for officers facing angry crowds during street demonstrations, it is a Plexiglas face shield for a police helmet. Police helmets already used Plexiglas face shields, but the city of Philadelphia approached the Rohm and Haas Company to see if it could help develop something that could stop a bullet fired at close range. The Department tested a number of face shields of increasing thickness, and this one finally stopped a bullet. Face shields like this one were never used, however, because they proved impractical in another way: weighing just over three and one half pounds, they were too heavy for officers to carry along with their other equipment. Although the experiment failed, it foreshadowed the subsequent use of Plexiglas and other clear plastics as “bandit barriers” to deter robberies of banks and stores.

When the first sheets of clear Plexiglas rolled off the machines in Darmstadt and Bristol, no one knew what its uses would be. Was anyone thinking about jukeboxes in the 1930s, much less bombardier enclosures or millions of back-lit signs? The many uses of Plexiglas developed by Rohm and Haas demonstrated innovation in technology, a hallmark of Philadelphia industry. The region’s innovators have included such industrialists as saw manufacturer Henry Disston (1898-78), hat-maker John B. Stetson (1830-96), and radio builder A. Atwater Kent (1873-1949). As they built companies that employed thousands of Philadelphians in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, like the maker of Plexiglas they each used creative intelligence and technology to develop products that met contemporary needs.

Text by Jeffrey Ray, Senior Curator of the Philadelphia History Museum for 29 years and now retired. He keeps himself busy teaching at the University of the Arts, Drexel University, and St. Joseph’s University.

Click here to watch a Rohm and Haas film, “Looking Ahead Through Plexiglas” (1947, via YouTube).