Automobile Suburbs

By Carolyn T. Adams | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

In the twentieth century the internal combustion engine brought massive change to the region, as households and industrial producers increasingly relied on automobiles and trucks to conduct daily business. Philadelphia and Camden factory owners moved their plants to cheaper locations in nearby suburbs, especially those near highways. Assisted by the Federal Housing Administration and the Veterans Administration, residents of Philadelphia and Camden also moved to the suburbs, where the family car expanded housing choices beyond the towns served by streetcars and rail lines. While the advantages conferred by the new suburban lifestyle were obvious, few people fully appreciated the social challenges that the automobile would create.

Early twentieth-century developers built one of the first auto-centered residential neighborhoods just inside the Philadelphia city limit. Later designated on the National Register of Historic Places as the “Cobbs Creek Automobile Suburb District,” this community sat adjacent to the newly created automobile parkway along Cobbs Creek, which formed part of Philadelphia’s western boundary. The neighborhood’s rows of two- and three-story houses, constructed mostly in the first quarter of the twentieth century, accommodated the family automobile with rear alleys and rear basement garages. Once Henry Ford introduced assembly line production in 1914, he began selling automobiles at prices that middle-class households could afford. Car ownership increased dramatically during the 1920s, accelerating middle-class suburbanization in both Pennsylvania and New Jersey. The Delaware River Bridge, which opened in 1926 (later known as the Benjamin Franklin Bridge), forged an easy connection between the two states.

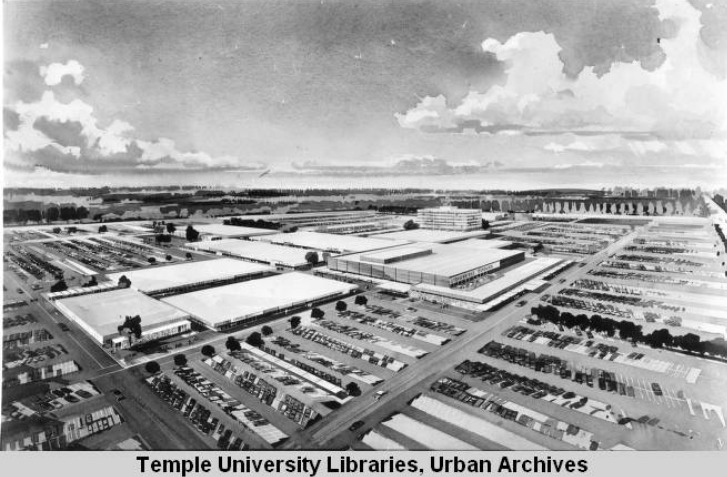

Some of the earliest suburbs in the region became hubs of the much-larger suburban wave following World War II. An example is the community of Delaware Township in Camden County, which was subsequently renamed Cherry Hill. There, white-collar professionals sought a suburban lifestyle at mid-twentieth century. To serve this affluent population, developers started construction on the Cherry Hill Mall in 1960, opening it a year later as the first enclosed shopping mall on the East Coast.

Manufacturing Moves to the Suburbs

Not only did stores and services follow the central city populations migrating outward to the suburbs. Manufacturing firms as well left older urban industrial districts for the green fields beyond the city limits. The owners of industrial plants in Philadelphia, Camden, and Chester played an early role in shaping twentieth century suburbs. The federally funded interstate highway system launched in the 1950s made it convenient for them to move their plants out of nineteenth-century industrial districts to cheap land at the edge of the city. There they replaced their multistory operations with one-story plants that accommodated continuous-flow production processes. They favored locations near highway on-ramps, where they could dramatically reduce the time it took truck drivers to deliver raw materials and pick up finished goods. Since suburban plants were typically more automated than older urban factories, owners could also save money on labor. For example, RCA, long a mainstay of Camden’s industrial economy, moved a significant part of its offices and laboratories to Cherry Hill in 1964. Camden’s combined losses of retail and manufacturing employment to Cherry Hill were so significant that by 1965, Cherry Hill’s assessed property value surpassed that of Camden, deepening the economic challenge facing that aging city. This pattern of industrial flight to the suburbs undermined the economic stability of all the older manufacturing districts in the Greater Philadelphia region.

Lower taxes and municipal incentive packages helped lure industries to the suburbs. The historic fragmentation of the region’s land area into hundreds of separate municipalities led to competition among townships for business investment. Relying mostly on automobiles and trucks, businesses gained the freedom to distribute themselves broadly across the suburban landscape rather than clustering. By the dawn of the twenty-first century, early manufacturing suburbs had lost ground to newer locations. or example, lower Bucks County began losing its industrial job base as companies chose locations in upper Bucks County.

Households Pursue the Suburban Dream

Federal funds for building highways in metropolitan areas constituted only part of the national government’s spur to suburban growth following World War II. In addition, the G.I. Bill of 1944 provided low-interest loans to veterans for buying single family homes, fueling the exodus from older residential neighborhoods in Philadelphia, Camden, Wilmington, and Chester City. In 1940 the city of Philadelphia contained 57 percent of the total population living in nine counties that the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission defined as the Greater Philadelphia region. By the year 2000 that figure had plummeted to 28 percent.

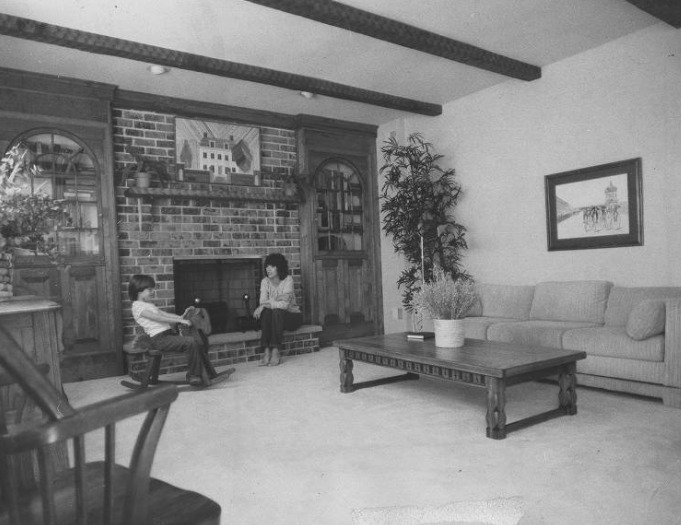

houses, as is shown in this photograph of a Bucks County split-level home in 1973. (Special Collections Research Center, Temple University Libraries)

The suburbs built beyond the city limits at mid-twentieth century featured one-story or split-level houses, each home surrounded on all sides by its own grassy yard. Typically, builders offered a limited number of house plans and architectural styles, most of which offered either a side garage or a carport, building the automobile into the culture of the families who bought them. That move of the automobile from back alley to the front yard of the home signified the growing importance of the car in suburban life. New suburbs typically arranged homes along slow-speed, curvilinear streets just wide enough for emergency vehicles to turn around. Surrounding these residential enclaves, shopping malls, drive-through restaurants, and drive-in movie theaters lined suburban highways to serve the car-owning population. By the late 1950s these services began to cluster in early shopping centers surrounded by massive parking lots.

Highway intersections in the suburbs often determined the locations of early shopping malls. In 1966 the Baltimore-based Rouse Company built Plymouth Meeting Mall near the interchange where the Pennsylvania Turnpike (I-276) crossed the Northeast Extension/Blue Route (I-476). Developers strategically located the King of Prussia Mall where the Schuylkill Expressway intersected with the Pennsylvania Turnpike. The 1960s also saw the building of the Moorestown Mall near the intersection of Interstate 295 and N.J. Route 73. Satisfying so many household needs, these and numerous other shopping centers gave suburban homeowners fewer reasons to drive into Philadelphia, Camden, or Wilmington.

Civic Leaders Accommodate the Automobile

Recognizing the threat posed by this tide of suburbanization, Philadelphia leaders focused on auto-friendly projects that would maintain the centrality of downtown as the center of a region that increasingly relied on cars and trucks. To make it easy for drivers to access downtown from any point on the suburban fringe, downtown planners designed a loop of expressways around the city. First came the Pennsylvania Turnpike, crossing the region from west to east across the northern suburbs. On the western side of the central city, the Schuylkill Expressway opened in 1958, connecting the city to King of Prussia, which became one of the largest suburban shopping and office complexes in the United States. Across the city on its eastern edge, construction crews in 1966 began building I-95 among the Delaware River to connect the city with northern suburbs in Bucks County and Mercer County. In 1959 engineers opened a depressed expressway across the north edge of downtown with limited access between Twenty-first Street and Seventeenth Street. Then in 1991 they extended the eastern portion of that Vine Street Expressway all the way to the Delaware River at the city’s eastern edge.

Ultimately, however, those efforts by Philadelphia planners could not stem the rise of the suburbs. Growing segments of the suburban workforce both lived and worked outside the city limits. The automobile enabled businesses to disperse along major auto routes, rather than clustering in a handful of edge cities. That dispersed pattern of employment produced increasing traffic flows from suburb-to-suburb, breaking the spoke-and-wheel pattern that had marked earlier commuting by streetcar and rail.

While the negative impacts on the city are well-known and documented, urban analysts have paid less attention to the consequences for the inner suburbs. Mass auto ownership reduced their competitive advantage, which had been based on their easy access to downtown Philadelphia via mass transportation. Even families in suburbs served by the extensive regional rail service acquired cars because the entire suburban landscape was developed to require automobiles in everyday life for travel to schools, churches, shopping and services of all kinds.

The Automobile Enables Sprawl

Rather than locating most services, entertainment, and employment in town centers where they could be reached on foot, the automobile encouraged real estate developers to spread out those everyday destinations. Admittedly, some stores, restaurants, and services were clustered in strip malls or enclosed shopping malls, but almost all accommodated the automobile. Both commercial and residential developers sought large tracts of suburban land on which to build— a practice that worked against a consistent pattern of outward expansion. Builders constantly leapfrogged over already-developed areas in order to acquire cheaper land that was not near already-developed territory. The resulting pattern created broadly scattered subdivisions and commercial and industrial development. That scattering reinforced the necessity of car travel as a requirement of life in the suburbs.

The one consistent element in all suburban plans was parking space for autos and trucks. Not just shopping centers, but also schools, hospitals, medical centers, and office complexes provided free parking as a matter of course. Often zoning boards required developers to assure at least one space per employee, and the easy availability of free parking led commuters to drive alone to work. The absence of sidewalks in many suburban commercial and office districts, along with the prospect of crossing massive asphalt parking lots, discouraged both walking and transit use in the suburbs.

In 2001 a civic coalition including the Pennsylvania Economy League, 10,000 Friends of Pennsylvania, The Reinvestment Fund, and the William Penn Foundation sounded an alarm about the impacts of sprawl in metropolitan Philadelphia. Between 1970 and 1990, population in the nine-county area served by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) had barely increased from 5.12 million to 5.18 million, slightly more than 1 percent. Yet in those same twenty years, total developed land had expanded by 30 percent, which amounted to paving over one additional acre every hour.

The Automobile Contributes to Pollution

The spread of massive suburban parking lots especially affected water quantity and quality. Paving over land that could otherwise filter rainwater reduced the amount of water recharging suburban aquifers, which often serve as primary sources of drinking water. Stormwater draining off paved areas heightened the potential for flooding. And the proliferation of impervious parking surfaces in suburban locations increased the quantity of contaminants being washed into local streams, rivers, and lakes by stormwater runoff.

Even more threatening than the automobile’s impact on water quality was the air pollution generated by auto exhaust. Philadelphia’s embrace of the automobile in the 1950s and 1960s blinded some civic leaders to this threat. A 1969 DVRPC transportation analysis (projecting the region’s needs and conditions in 1985) drew blistering criticism from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency for its heavy emphasis on accommodating automobiles at the expense of public transportation and environmental quality. Specifically, the federal agency criticized the DVRPC for planning to spend three times as much money on limited access roads as on mass transit. To dramatize their criticism, the EPA representatives staged their news conference on an incomplete section of the I-95 highway.

Subsequent trends confirmed the EPA’s fears about the impacts of auto transportation on the region’s air quality. From 1990 to 2019, the amount of greenhouse gas emissions produced by autos and trucks in the Philadelphia metropolitan area increased faster than the population grew, according to Boston University’s Database of Road Transportation Emissions. Among the neighborhoods burdened with the most auto-related pollution were Old City, Northern Liberties, Callowhill, and Chinatown — all areas adjacent to the Vine Street Expressway, which community leaders in Chinatown had fought bitterly. Suspecting the massive expressway project would damage their district, they had demanded unsuccessfully that the submerged road be capped, at least in their vicinity.

Not only inside the city, but also in the suburbs, dependence on the automobile endangered air quality at the turn of the twenty-first century. The single largest contributor to ozone was automobiles on congested roads. Lower Bucks County consistently recorded some of the highest smog levels in Pennsylvania, increasing the risk of cardiovascular disease and strokes. In some years, the two Bristol census tracts bordered by I-95, the Pennsylvania Turnpike, and Route 3 recorded the highest asthma rates in the United States, exceeding 10 percent of adults. Advocates for cleaner air proposed that employers in Lower Bucks County allow employees to work from home on days with poor air quality, or organize ride-sharing, and reduce the company’s use of motor vehicles.

Automobile Culture and Social Separation

Among the most important long-term effects of the automobile culture was to enable social separation of residents by income and race in the Philadelphia suburbs. As the suburban job base ranged across long distances (instead of concentrating in industrial districts like those within the central city), commuters needed daily access to an automobile. That requirement prevented many lower-income Philadelphians from living in the suburbs.

Since the car made it possible to live at significant distances from workplaces, the fortunate families who could afford suburban homes enjoyed the freedom to select their neighborhood based on factors other than the journey-to-work, newcomers made choices based on the price of housing, the kinds of services and amenities that different communities provided, and the kinds of people they preferred as neighbors.

In some suburbs, trends toward income, racial, and ethnic separation were reinforced by restrictive covenants, sales, rental or financing opportunities, and real estate agents who steered African American buyers away from all-white neighborhoods. Suburban residents engaged in such practices not only to live among compatible neighbors, but also to preserve the value of their houses. The resulting pattern separated the suburban population into homogeneous enclaves. By the 1970s, the social mixing of residents that had been common in earlier streetcar suburbs had become distinctly uncommon in suburbs. Inner suburbs had become home to many working-class and immigrant households. In contrast, the greatest number of middle-class suburbs were arrayed at the outer edges of the metropolitan area, where land prices were affordable. The suburban towns with the highest household incomes in the region clustered in Pennsylvania at mid-distance between downtown Philadelphia and the region’s edge, where land prices had risen historically in older suburbs served by commuter railroads.

Recovering Walkable Townscapes

At the opening of the twenty-first century, suburban planners faced changing consumer preferences that affected suburban planning. The dominance of shopping malls as retailing centers had begun to erode in competition with online shopping. Several of the region’s largest malls had suffered serious declines. At the same time, young adults appeared less committed to auto ownership than their parents’ generation and more inclined to favor walkable environments for recreation, shopping, and entertainment. To accommodate the growing interest in walkable communities, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 2014 began publishing a “National Walkability Index” because walkability had emerged as an important factor in real estate markets across the nation.

The Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission encouraged redevelopment of walkable suburban centers with its Classic Towns initiative carried on between 2008 and 2018. That program encouraged and publicized a group of suburbs working to encourage pedestrian traffic by investing in walkable commercial districts. Typically, their Main Street improvements included historic preservation of stores, office buildings, restaurants, bars and movie theaters, plus the addition of street trees and other greenery, historic lighting fixtures, and benches for sitting.

Some of those walkable suburbs served as county seats (for example, Doylestown and West Chester), while others developed lively town centers around regional rail stops (for example, Ambler and Collingswood). Such town-based initiatives, while they certainly could not eliminate the place of the automobile, could at least signal the end of its overwhelming dominance in suburban life.

Carolyn T. Adams is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and associate editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Information in this essay was current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History