Avenue of the Arts

Essay

The Avenue of the Arts is the appellation for a section of Broad Street—from Washington Avenue in South Philadelphia to Glenwood Avenue in North Philadelphia—devoted to arts and entertainment facilities. The Avenue was conceived in 1993 by a coalition of public and private entities to attract visitors to Center City. Amid a decline in manufacturing, promoting entertainment amenities seemed like a sure way to revive moribund commercial areas and increase tax revenues. Rebranding Broad Street as a performing arts destination was part of the city’s broader push to bring suburbanites and tourists to downtown Philadelphia.

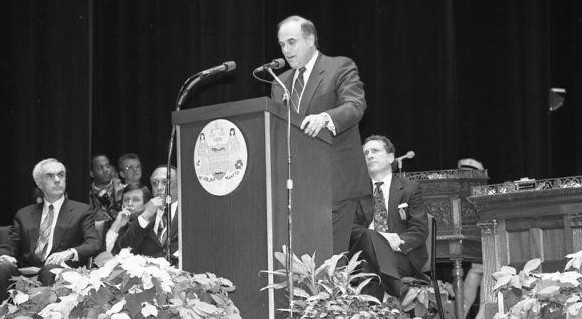

In the 1980s, South Broad Street was in the midst of a long decline. Massive nineteenth-century office buildings that had once housed banks and law firms sat empty, their tenants fleeing to newer skyscrapers and suburban office parks. Few street-level businesses remained. When he was elected, Mayor Edward Rendell (b. 1944) found South Broad Street almost entirely barren. “On a Saturday night in 1991,” he remembered, “you could walk the mile from City Hall to Washington Avenue and you wouldn’t have seen 100 people.” Although a handful of arts-focused institutions persisted—the University of the Arts, the Shubert Theatre, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts—they suffered from the broader decline in Broad Street’s fortunes.

Upon entering office in 1992, Rendell searched for a project that would help to revitalize the city—improving its image, spurring real estate development, and encouraging tourism. South Broad Street, which already had two redevelopment plans in motion, seemed ideal. Since 1977, the Old Philadelphia Development Corporation (OPDC) had tried to revitalize Broad Street by capitalizing on its existing arts facilities. OPDC created the Avenue of the Arts Council (and later, Academy Center Inc.) to direct its activities on Broad Street and raise funds for a new orchestra facility to replace the undersized Academy of Music. And in 1989, the William Penn Foundation had launched the South Broad Street Cultural Corridor plan, which aimed to bring several smaller arts venues to the area.

A Coalition Tries Again

In order to unify renewal efforts, Rendell took control of the nonprofit Avenue of the Arts Inc. (AAI) in 1993. The AAI brought together a coalition of pro-growth forces, including the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC), philanthropic foundations, local businesses, and real estate developers. Its board also included Rendell’s wife, Judge Marjorie O. Rendell (b. 1947). The AAI attracted funding from the state, philanthropist Walter H. Annenberg (1908–2002), and dozens of local corporations.

Initially, AAI focused its efforts on the blocks of South Broad Street between City Hall and South Street. It devoted $3.7 million to open the ArtsBank, a venue in a renovated bank building (completed in 1994); $2.4 million towards the Clef Club jazz hall and archive (completed in 1995); $6.1 million to build the 300-seat Wilma Theater (completed in 1996); and $24 million to convert the vacant Ridgeway Library building into the Philadelphia High School for Creative and Performing Arts (completed in 1997). AAI also poured money into streetscape improvements, installing new signage, sidewalks, and lampposts. In its first decade, AAI invested $378 million in the Avenue, with $75 million of that total coming from the state and $30 million from the city.

Meanwhile, negotiations continued over the Philadelphia Orchestra’s new home. In 1998, architect Rafael Viñoly (b. 1944) announced designs for a $203 million, 2,500-seat concert hall on South Broad Street. In 2000, the facility was renamed the Kimmel Center after philanthropist Sidney Kimmel (b. 1928), who donated $15 million towards its construction. The Kimmel Center finally opened to mixed reviews in 2001, $100 million dollars over its initial budget.

Extending to North Broad

In 1995, AAI announced that it planned to extend the Avenue of the Arts onto North Broad Street, promising to devote $60.6 million to the disinvested corridor. The AAI initiative specifically targeted African American cultural institutions, including the Freedom and Uptown Theaters and the historic Blue Horizon boxing gym. While the northern portion of the Avenue received far less investment than South Broad Street, several new residential projects opened in the 2000s, including the AAI-supported Lofts at 640 Broad Street and the Avenue North buildings. In 2011, the Pennsylvania Ballet broke ground on its new rehearsal facility, the Louise Reed Center for Dance, on North Broad Street near Callowhill Street.

By the 2000s, the Avenue of the Arts had proven to be a financial success. In 2012, the Greater Philadelphia Cultural Alliance reported that jobs created by arts and culture institutions in Philadelphia generated over $490 million dollars in wages. The Avenue of the Arts itself, one 2007 study claimed, generated $150 million in earnings for its approximately 6,000 employees. Ex-Mayor Rendell marveled that “when you walk around [the Avenue] on a Thursday night, you see thousands of people on the street. It’s not yet complete, but it’s come a long way.” Those thousands of visitors spent approximately $84 million per year at restaurants and hotels along the avenue. Still, the Avenue was not an unqualified triumph. Tax proceeds from performing arts venues along the Avenue remained modest, totaling only $10 million in 2006, in part due to tax abatements and incentives the city had offered to attract businesses and developers. Once initial subsidies from the William Penn Foundation ended in 1997, the Arts Bank was forced to close. The Kimmel Center’s tenants, including the Opera Company of Philadelphia and the Pennsylvania Ballet, struggled to pay rent at the new facility. The Philadelphia Orchestra flirted with bankruptcy due to budget shortfalls and low attendance.

In the 2000s, AAI began to encourage residential construction that capitalized on the Avenue’s arts-related cachet. AAI’s partner, PIDC, held design competitions for several empty lots on Broad Street. Developer Carl Dranoff (b. 1948) won the rights to build Symphony House, a 31-story luxury condominium building at Broad and Pine Streets, in 2002. Its ground floor housed the 365-seat Suzanne Roberts Theatre, the new home for the Philadelphia Theatre Company. PIDC also granted Dranoff permission to build two other mixed-use buildings on South Broad Street, the 777 at Broad and Fitzwater Streets and SouthStar Lofts at Broad and South Streets.

These projects pointed towards the Avenue of the Arts’ future as a mixed-use corridor. As retirees and young people moved back to Center City, the Avenue added businesses to serve them. The historic buildings on South Broad Street never attracted many new offices, but they began to fill with other tenants—hotels, restaurants, retail shops, and apartments. At the same time, the University of the Arts expanded its own footprint along South Broad Street, with classrooms, galleries, and a performing arts theater. Organizations like Wells Fargo and the Union League opened small museums or increased their exhibit spaces, enhancing the appeal of the Avenue of the Arts as a destination area. Drawing tourists and regional visitors for shows, performances, and exhibits, and other entertainment, the Avenue of the Arts initiative sparked widespread residential and commercial development along Broad Street.

Dylan Gottlieb, a Ph.D. candidate at Princeton University, works on recent American urban history. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Uptown Theater revival (WHYY, April 25, 2011)

- Troupe movement: Pennsylvania Ballet relocating to N. Broad space (WHYY, October 10, 2011)

- Kimmel’s Volver puts Garces' culinary life center stage on Avenue of the Arts (WHYY, February 11, 2014)

- PAFA celebrates alum David Lynch with 'Unified Field' (WHYY, September 11, 2014)

- The Prince Music Theater's template became the norm (WHYY, October 29, 2014)

- Nézet-Séguin leads Philadelphia Orchestra into a new season (WHYY, October 1, 2015)

- Philadelphia Orchestra will bring to light music from City of Light as part of next season (WHYY, January 19, 2016)

- A tale of two Broad Streets: How Avenue of the Arts splintered (WHYY, June 20, 2016)

- Boyz II Men Boulevard is more than a street name for Philadelphia natives (WHYY, June 25, 2017)

- Restored to former glory, The Met opens on North Broad Street (WHYY, December 3, 2018)

- Philly's Avenue of the Arts to spend $100 million greenifying South Broad Street (WHYY, July 9, 2024)

Links

- It Wasn't Always the Avenue of the Arts (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Lost on Broad Street (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Dranoff's Broad Street Skyscraper: It's Official Now (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Freedom Theater Historical Marker (ExplorePaHistory.org)

- Edwin Forrest: A Legend of American Theater (PhillyHistory Blog)