Black Power

Essay

Black Power, a movement significant to the Black freedom struggle in Philadelphia, came to prominence in the 1960s and 1970s through the combined efforts of local and national organizations including the Church of the Advocate, the Black Panther Party, the Black United Liberation front, and MOVE. Before and after Stokely Carmichael (1941-98) of the national Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) invoked the term Black Power in 1966, African American activists in the Philadelphia region fought for economic equality, educational equity, improved living conditions, and an end to police brutality.

Many advocates of Black Power had ties to the civil rights movement, but during the 1960s they diverged from its nonviolent stance and emphasized Black identity and empowerment through anti-poverty programs, self-defense, and diasporic connections with other oppressed people. Black Power stressed that Black people should be in control of Black communities. In Philadelphia, early Black Power initiatives included projects to raise awareness of African and African American history and culture, including the Freedom Library on Ridge Avenue in North Philadelphia, opened in 1964 by John Churchville (b. 1941). Churchville and other activists who gathered at Freedom Library formed Philadelphia’s first Black Power political organization, the Black People’s Unity Movement (BPUM), in 1965. An organization by the same name formed in Camden, New Jersey, in 1967.

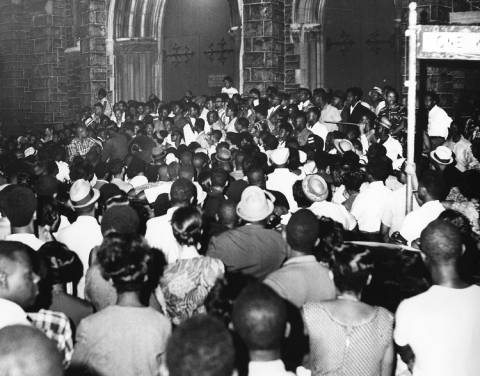

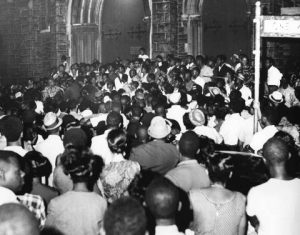

In North Central Philadelphia, the Church of the Advocate, with a congregation becoming increasingly African American as whites moved out of the city, became an important center of Black Power. Under the leadership of Father Paul Washington (1921-2002), one of the Freedom Library activists, the church and BPUM hosted a Black Unity Rally in February 1966 that drew a capacity crowd to hear civil rights leader Julian Bond (1940-2015). Black Power rallies followed in locations around the city during the summer, including two attended by Stokely Carmichael (1941-98). In 1968, the Church and BPUM also hosted the Third National Conference on Black Power, attended by two thousand people and leading to the creation of the Advocate Community Development Corporation and a Black activist newspaper, Voice of Umoja.

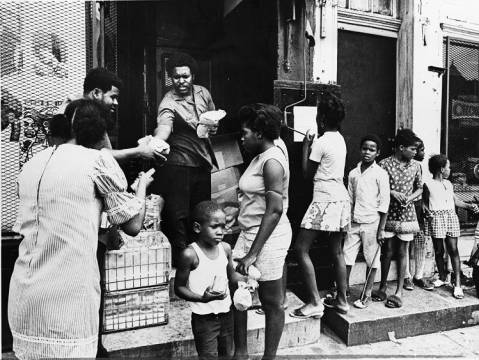

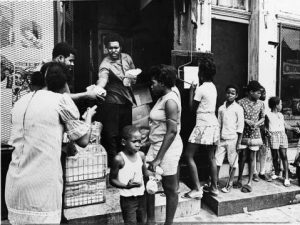

Church of the Advocate members included Reggie Schell (1941-2012), who in 1969 became the defense minister (leader) of the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panther Party. The Black Panthers originally formed in 1966 in Oakland, California, to patrol and protect African American neighborhoods from police brutality. In Philadelphia, under Schell’s leadership the local chapter expanded from its base in North Philadelphia to become influential throughout the city through a “Free Food for Survival” program, education programs, rallies, and other political events. The Black Power movement also spread to the region’s college campuses, where sit-ins called for Black faculty and Black studies programs, and to high schools. Activism focused especially on control of the Philadelphia public schools. When Black students from a dozen Philadelphia high schools marched on a Philadelphia Board of Education meeting on November 17, 1967, with demands including Black history classes taught by Black teachers, many wore Black Power buttons.

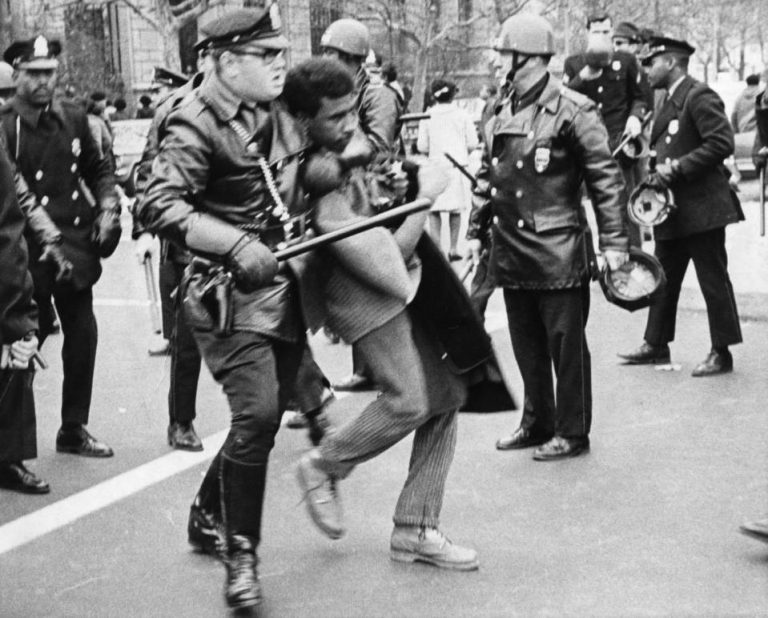

The rising tide of Black activism and militancy so alarmed the Philadelphia Police Department that even the students marching on the school board were met with nightstick-wielding officers, commanded by then-commissioner and future mayor Frank Rizzo (1920-91). Police raided homes of Black Power activists and offices of organizations, and many local activists were followed by FBI agents from COINTELPRO, a counterintelligence program that aimed to infiltrate U.S. political organizations, including the Black Panther Party. (COINTELPRO was discovered in 1971, when activists raided the Media, Pennsylvania, office of the FBI.)

On August 31, 1970, shortly before a Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention held at Temple University and following a shooting of a white police officer by an African American man, Philadelphia police raided three Black Panther Party headquarters, including one near the campus on Columbia Avenue. The raids became internationally known for their brutality and visibility. Panther members were held at gunpoint and many were publicly strip-searched before being taken to the police station. The bail for the Panthers was set at $100,000, but it was posted by the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of the Society of Friends. The raids, ordered by Rizzo, did much to unite the NAACP and other stalwarts of the nonviolent civil rights movement with the Panthers. Although not entirely aligned politically, many Philadelphia activists united in their opposition to police brutality.

Despite the raids, the Revolutionary People’s Constitutional Convention took place as scheduled at Temple University’s McGonigle Hall in September 1970. The convention drew fourteen thousand participants, including Black Panther Party leaders from across the country, to hear speakers including Huey Newton (1942-89). Activists gathered to draft a new constitution and attend workshops at the event, which the Black Panther Party declared successful. Many attendees, primarily women, felt differently and critiqued the masculinity and misogyny apparent in many of the activities. Still, the convention was one of the largest gatherings of radical activists in the United States.

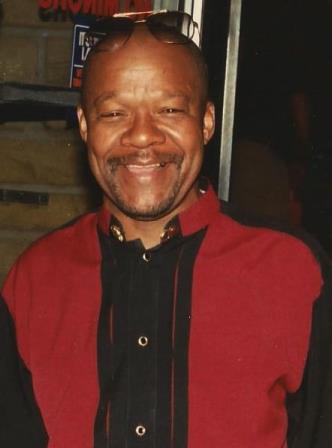

Although the Black Panther Party declined in influence in the early 1970s, many activists turned their interests toward diasporic connections and global injustice. Black Power activists in Philadelphia, for example, founded the Philadelphia Coalition to Stop Rhodesian and South African Imports to protest apartheid in South Africa. By the early 1970s, the Philadelphia chapter of the Black Panther Party disbanded but Reggie Schell and other local Panthers started the Black United Liberation Front, which continued much of their activism.

The legacy of the Black Power activism lived on among other Philadelphia organizations and individuals. Black Power activism changed Philadelphia-area politics by making issues important to African Americans central to local governance and, eventually, by electing movement veterans to office. W. Wilson Goode (b. 1938), a West Philadelphia community organizer, became managing director of Philadelphia and then the first of three African American mayors, serving from 1984 to 1992. Other veterans of the Black Power movement gained seats in the Pennsylvania General Assembly.

Although many have cited the disbanding of the Black Panther Party and the pursuit of prominent Black Power activists by law enforcement as a failure of the movement, the Black Power movement left an important legacy in Philadelphia and across the country. The Church of the Advocate in North Philadelphia remained active in community-centered actions and social justice work, hosting a daily soup kitchen and youth programming. Prominent Philadelphia Black Panthers included Mumia Abu-Jamal (b. 1954), who joined the Black Panther Party at fourteen and became the local chapter’s “lieutenant of Information.” His incarceration for the 1981 murder of Philadelphia Police Officer Daniel Faulkner (1955-81) and assertions of an unfair trial prompted global activism on his behalf. While imprisoned, Abu-Jamal became a vocal writer and activist for the rights of incarcerated people. Activists also pursued the release of jailed members of MOVE, the black nationalist and anarcho-primitivist organization famously bombed by Philadelphia police in a 1985 standoff at a MOVE compound in West Philadelphia.

In both city government and radical activism across Philadelphia, the teachings and legacy of Black Power in Philadelphia remained prevalent. The Black Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s created the space for continued activism and political presence for African Americans in Philadelphia.

Holly Genovese is a Ph.D. student in history and Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Temple University. Her interests are in incarceration, public history, and Black Power. She is Contributing Editor at Auntie Bellum Magazine and a contributor at Book Riot, Rabble Lit, and the Us Society for Intellectual Historians blog. Her writing has been featured in Bustle, The Establishment, and Scalawag Magazine. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Oral History Interview with John Churchville (Library of Congress)

- The Reverend Paul Washington (Archives of the Episcopal Church)

- Photograph of Police Raid at Black Panther Headquarters, August 1970 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Africana Age: Rethinking the Black Power Movement (New York Public Library)

- Revolutionary Movements Then and Now: Black Power and Black Lives Matter (National Archives)

- Black Power (National Archives)

- Historic Marker for '85 MOVE bomb site (The Philadelphia Tribune)