China Trade

Essay

First pursued by the city’s merchants after the American Revolution, the China trade linked Philadelphians to the rest of the world through commerce. Alongside merchants in New York, Boston, and Salem, Philadelphians were pioneers in the trade, risking their ships and capital in new long-distance sailing routes that crisscrossed the globe to generate the silver coin and exotic commodities needed to make purchases in China. In exchange, the China trade provided Philadelphia and its hinterlands with teas, porcelains, silks, and spices, filling cupboards while boosting activity in shipbuilding, insurance, and banking. The global contacts the China trade provided defined Philadelphia as a cosmopolitan commercial center in the early American republic.

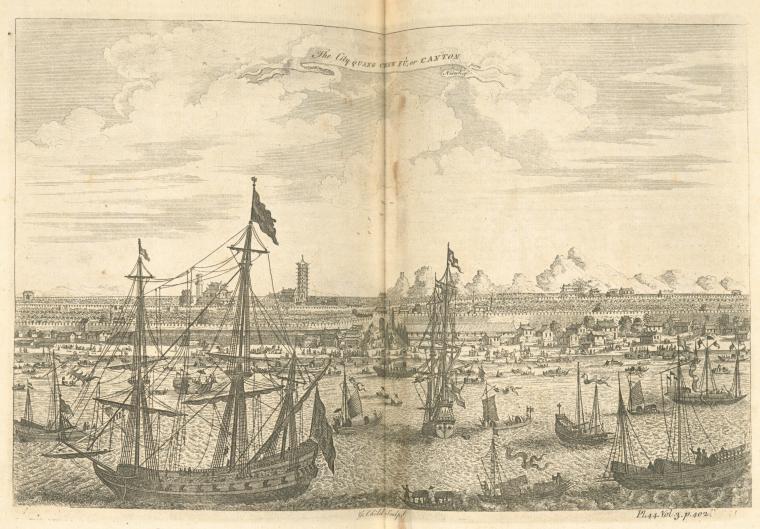

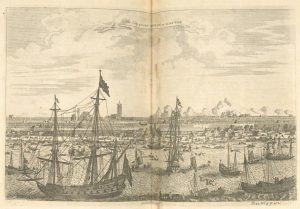

The China trade was a complex system of commercial circuits linking economies in the Atlantic world to those of what early Americans called the East Indies—the wide zone between the Cape of Good Hope and Cape Horn, encompassing China, India, Southeast Asia, and the Pacific islands. The traffic centered on Canton (Guangzhou), the biggest city of the Pearl River Delta and the only Chinese-controlled port open to Western traders. Beginning in the seventeenth century, Canton became the most important market for teas and Chinese manufactured goods. Lacking commodities in demand in Asia, westerners paid for their purchases in silver—usually Spanish dollars minted from New World silver mines—and accepted stringent regulations, including limiting their trading partners to a special guild of merchants, the Cohong, setting a specific season for all business, and confining them to rented factories (buildings that combined warehouses, offices, and living quarters) beyond the city’s walls.

Colonial Philadelphians, like other British subjects, developed a taste for Asian goods. However, access was mediated by the British East India Company, which held a monopoly on East Indies trade. In 1773, Parliament’s preferential treatment of the East India Company’s tea business helped spark widespread protests—most famously in Boston, but also in Philadelphia.

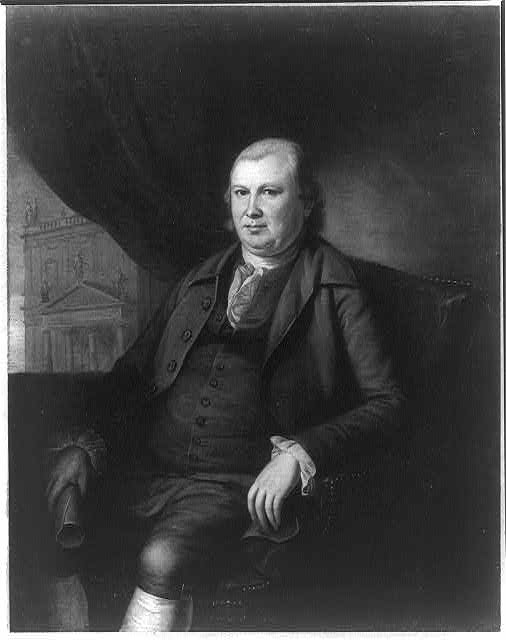

Philadelphia’s relationship to the China trade changed with the American Revolution. While the war gained Americans political independence, it cost them the markets of the British Empire, including the West Indian ports that Philadelphians depended upon as outlets for the region’s agricultural products. Faced with a dire economic situation, Philadelphians gambled on new trades—including with China. The first American ship to reach Canton, The Empress of China, departed New York harbor on February 22, 1784. It was a joint venture of Philadelphians and New Yorkers, organized by Philadelphian financier Robert Morris (1734-1806) and captained by Philadelphian John Green (1736-96). A financial success, the Empress’s voyage inspired imitators, which helped establish Philadelphia as a major center for U.S. trade with China.

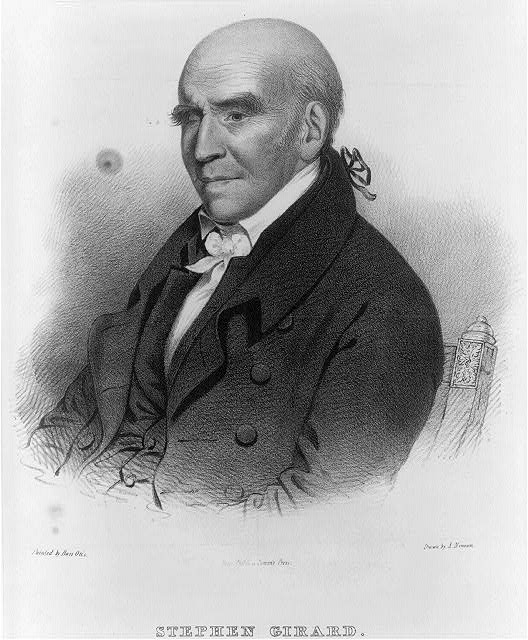

The founding generation of Americans saw their new trade with Asia as a matter of national pride as well as a source of prosperity. Philadelphia politicians used the establishment of a new federal government in 1789 to aid the trade, passing legislation that gave special protections to American merchants shipping East Indies goods. Still, bereft of cheap silver at home, and without all the monopoly protections of their European rivals, Philadelphian merchants like Stephen Girard (1750-1831) had to adapt to compete. They used smaller ships and crews to save on operating costs and more nimbly respond to markets. They also persistently sought new sources of Spanish dollars as well as new commodities that might sell well at Canton, including ginseng, sea otter pelts, sandalwood, and bêche-de-mer (sea slugs).

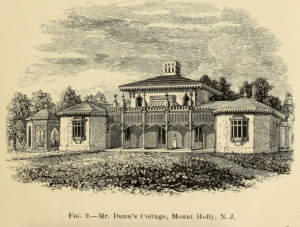

These innovations, along with good timing and a relaxed approach to commercial legality, were crucial to the trade’s early success. The Napoleonic wars provided neutral American shippers with an advantage as suppliers of tea to Europe, but also risked British interference. Philadelphia merchant Benjamin Chew Wilcocks (1776-1845) helped inaugurate an American opium-smuggling trade in 1805, shipping the drug to China from Smyrna (Izmir), Turkey, and later from British India. Well known as a painkiller, opium had become increasingly valuable in Asia as the practice of recreational smoking spread. Seeking to curb this addictive habit, Chinese authorities had long banned opium importation, though with little effect on smugglers’ business (the drug was legal in the United States). While not every Philadelphia merchant was an opium trader—a few, like Quaker Nathan Dunn (1782-1844), refused it on religious grounds—the illicit market for the drug was robust, and by the late 1820s, opium outpaced silver as the main import exchanged for goods in China.

Opium smuggling’s profits proved to be the undoing of the old China trade. The elaborate networks that British and American merchants created to facilitate opium trafficking caused friction with Chinese officials, culminating in Britain’s invasion in 1840 (the First Opium War). Though not belligerents, Americans benefited from Britain’s 1842 victory, as the treaties the Qing Empire made in its aftermath eliminated trading restrictions and opened new ports. Conflict over opium also accelerated consolidation among American China firms, which increasingly shifted their operations to New York. Philadelphia’s participation in overseas trade decreased, as its merchants invested in manufacturing, transportation, and domestic commerce instead.

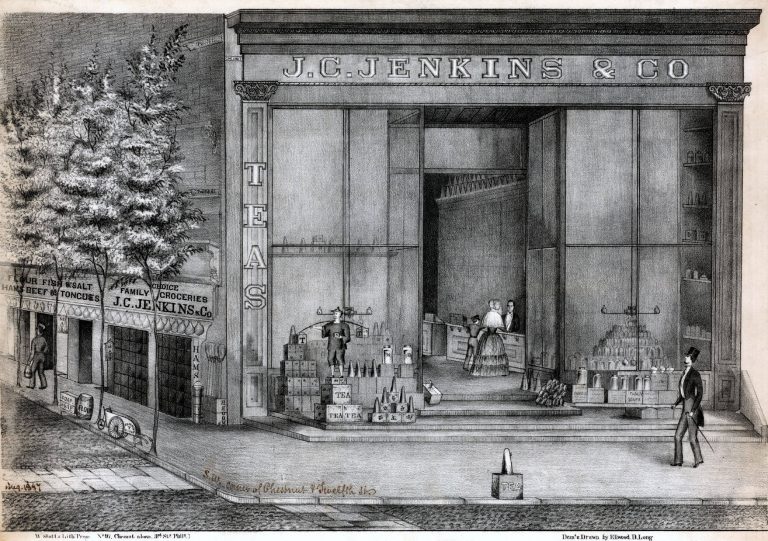

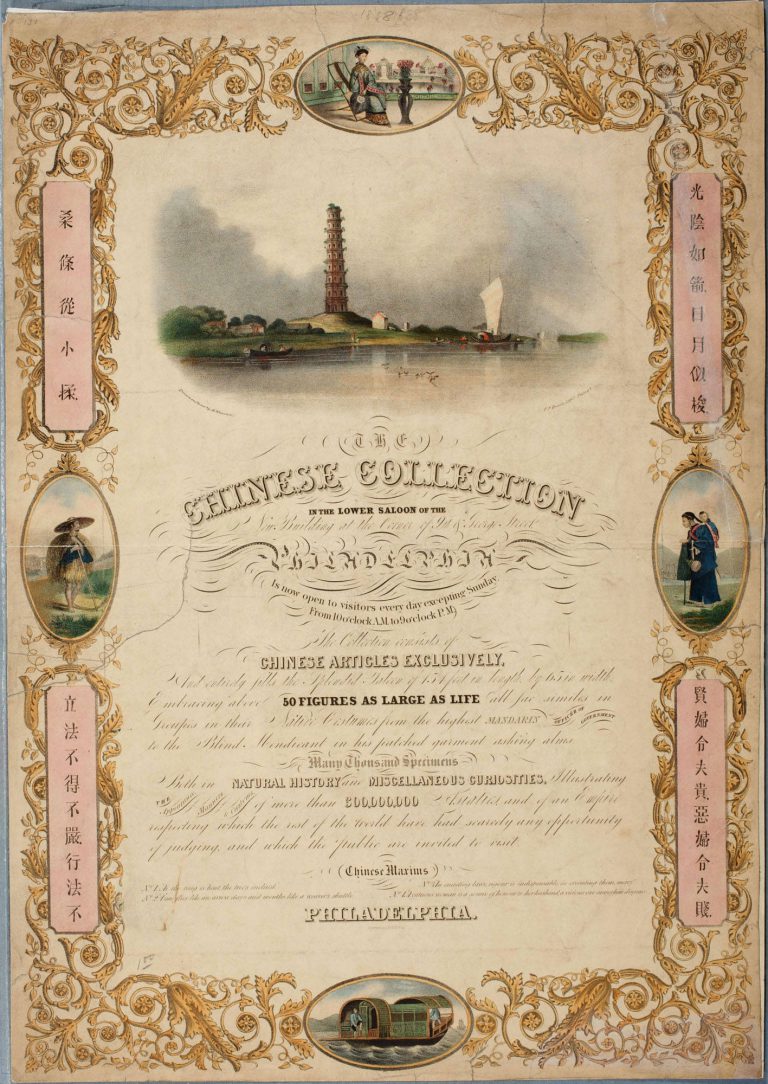

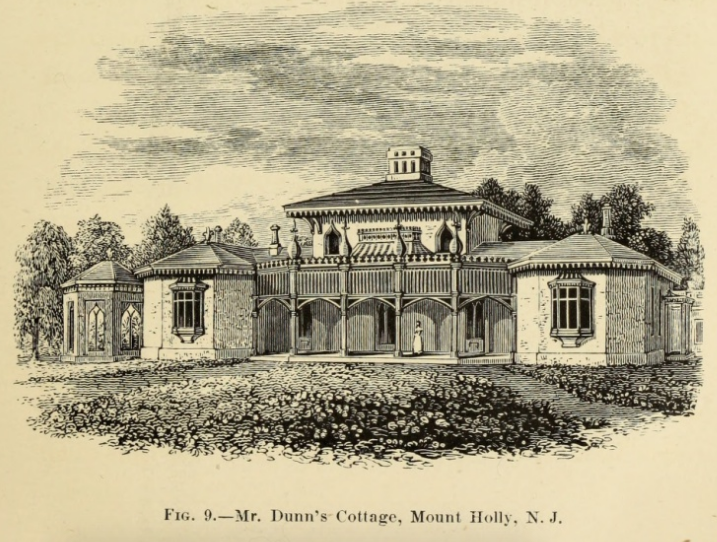

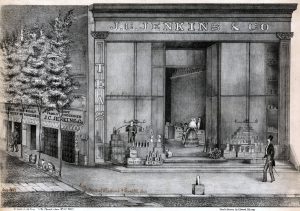

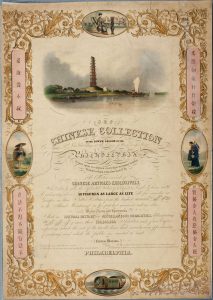

The China trade had a lasting impact on Philadelphia’s culture and society. Chinese goods were for decades markers of high status and fashion. China merchants were leaders in the commercial community, serving as bank and insurance company directors as well as members of the Philadelphia Board of Trade. Some of them, like Nathan Dunn and Andreas Everardus van Braam Houckgeest (1739-1801), built country estates in the Chinese style, filled with chinoiserie, and occasionally staffed by Chinese servants. Their fortunes also helped fund major charitable and educational institutions, including the American Philosophical Society, the Pennsylvania Hospital, and Girard College. The trade also influenced popular perceptions of China and its people among Philadelphians, long before any significant immigration from Asia. Grocers’ advertising for teas commonly featured Chinese people and landscapes, and beginning in 1839, Nathan Dunn’s Chinese Museum gave thousands of visitors an experience of “China in miniature” through dioramas of daily life in the Middle Kingdom. Through the China trade, Philadelphia came to know the world—and it, Philadelphia.

Dael A. Norwood is an Assistant Professor of History at Binghamton University. His book project, Trading in Liberty: How Commerce with China Defined Early America, examines how the lucrative commerce between the United States and China shaped the politics and political economy of the American state in its first century. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- China rising, U.S. declining? Don’t panic yet. (WHYY, November 4, 2011)

- Poll: More than half of Americans say China is the world economic superpower, not the U.S. (WHYY, March 21, 2014)

- Tourism officials aim to bring more visitors from China to Philly (WHYY, March 10, 2015)

- Bassetts Ice Cream sales to China could melt without Export-Import Bank (WHYY, September 3, 2015)

Links

- Made in China: Early American Trade with China, 1784-1844 (Yale University)

- Philadelphians and the China Trade, 1784-1844 (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- Early American Trade with China (University of Illinois)

- Cantonese Connection (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Rise & Fall of the Canton Trade System (Visualizing Cultures, Massachusetts Institute of Technology)

- Chinese American Exclusion/Inclusion (New York Historical Society)