Civil War

Essay

The Philadelphia region in many ways was a microcosm of the issues and experiences that defined and troubled the Civil War era. With close economic, political, and social ties to both South and North, Philadelphia and the surrounding region were torn in their interests and loyalties. The sectional crisis of the 1850s, the secession of southern states in 1860-61, and the war (1861-65) forced people to choose sides. The war tested the region as it responded to the military and manpower needs of the Union and then the consequences of war. Connections to the South declined dramatically, especially in Philadelphia, as the region’s identity and interests aligned more strongly with the nation and the Republican Party rose to prominence as a political force.

During the 1850s, expansion of slavery into western territories polarized the North and South, and southerners’ demands for the return of fugitive slaves and silencing of antislavery critics became increasingly intolerable in the North. Philadelphia and regional newspapers amply reported and stirred public comment and conflict about events such as the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 and the ensuing conflict over slavery in Kansas, which led to bloodshed as pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces fought a preview of the war that lay ahead. Further controversies arose over the Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision in 1857, the fracturing of the Democratic Party over the slavery issues, and the failed but far-reaching attempt by John Brown (1800-59) to foment an uprising of enslaved people in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October 1859.

Pro-southern sentiment ran strong in Philadelphia and the surrounding region. Economic ties with the South ran deep, especially in the textile, lumber, and coal industries, but also in education, banking, and marketing services. Some prominent families in the region owned plantations and many enslaved people, especially in Atlantic Seaboard states. Anti-Black and anti-abolitionist feelings also ran high. As a result, the increasingly pro-southern Democratic Party dominated not only Philadelphia but also New Jersey and Delaware. Although the newly emerging antislavery Republican Party (known in Pennsylvania as the People’s Party) gained supporters by the late 1850s, in the region it emphasized higher tariffs and a moderate position of opposing further extension of slavery into the western territories. Local Republicans played down any ties to abolitionists who insisted on the immediate, universal, and uncompensated end to slavery and the embrace of Black people as citizens.

A Magnet for Freedom Seekers

The John Brown raid and his execution by Virginia authorities, which northern abolitionists and others likened to martyrdom, inflamed tensions in Philadelphia. Editorials in Democratic, pro-southern newspapers lashed out at abolitionists as revolutionaries bent on racial violence, lawlessness, and even disunion. They equated abolition with the Republican Party, asserting that it aimed to promote equality between white and Black people. Philadelphia’s growing African American population and proximity to slave states made it a magnet for enslaved persons fleeing bondage. The increasingly effective work of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, vigilance committees, and the Underground Railroad network brought many freedom seekers into the city, further heightening tensions between abolitionists, African Americans, and Republicans on one side, and pro-southern supporters and Democrats on the other.

The sectional crisis came to a head in the election of 1860. “Fire-eating” southerners threatened to leave the Union if the Republicans won the presidency. But the Democratic Party had split into southern and northern wings, each nominating its own candidate for the presidency. Most northern Democrats threw their support behind Stephen A. Douglas (1813-61), and southern Democrats, along with many Philadelphians, supported Vice President John C. Breckinridge (1821-75). Complicating this already muddled field was the emergence of the Constitutional Union Party, a new third party committed to avoiding the slavery issue, which drew away votes from Democratic candidates. The Republicans offered a seemingly moderate ticket with Abraham Lincoln (1809-65)—the “rail splitter” from Illinois—at its head. To win the 1860 presidential election, Republicans needed only to hold onto the northern states they had won in 1856 and win Pennsylvania and either Illinois or Indiana. With fierce electioneering, the Republicans carried Pennsylvania. Douglas fared poorly, although he did win electors in New Jersey.

Following the Republican victory, seven southern states seceded, and efforts to bring them back during the “secession winter” from December 1860 to February 1861 failed, despite persistent efforts by prominent Philadelphia newspapers to rally support for compromise. As the Confederacy formed in the South, on February 21, 1861, president-elect Lincoln came to Philadelphia enroute to his inauguration and gave a powerful speech outside Independence Hall on the necessity of Union. His speech anticipated his inaugural address in Washington as he promised a firm hand to save the Union but an open hand to southerners that his administration would not disturb lawful existing institutions (meaning slavery).

After Fort Sumter, Pro-Union Stance Solidifies

The new Confederacy’s attack on Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina, on April 12-13, 1861, immediately changed the attitude of people in the Philadelphia region from conciliation to defense of the Union. It also led four more southern states to secede from the Union and join the Confederacy. On April 15, Lincoln called for seventy-five thousand volunteers for ninety days to put down the rebellion.

In Philadelphia those who had voiced support for the South now kept a low profile. Most pro-southern newspapers fell silent. Those that did not, such as the Palmetto Flag, came under threat of attack by enraged citizens. Philadelphia Mayor Alexander Henry (1823-83) readied police to oppose violence against persons or property. Throughout the war, he sought to maintain order through police presence whenever rumors of trouble loomed.

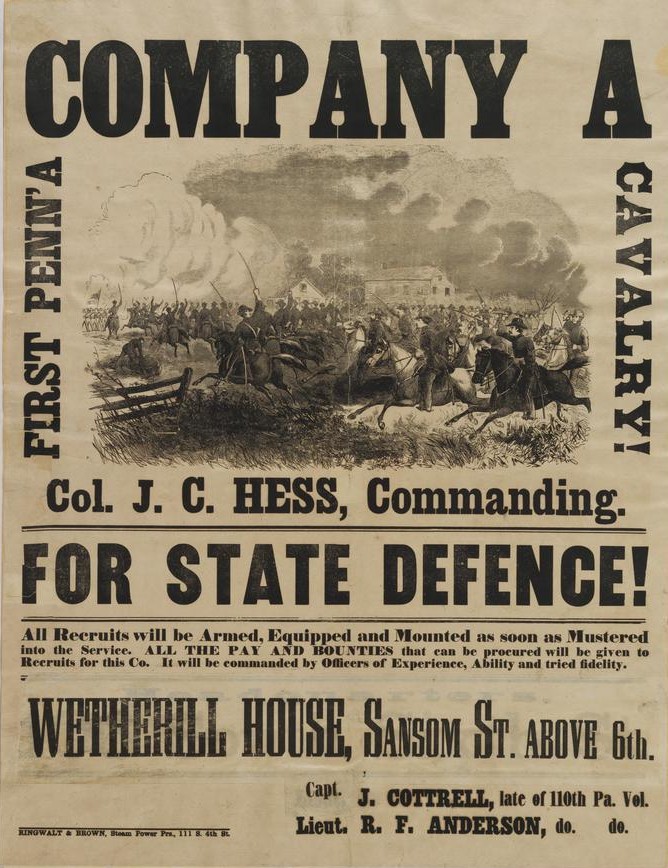

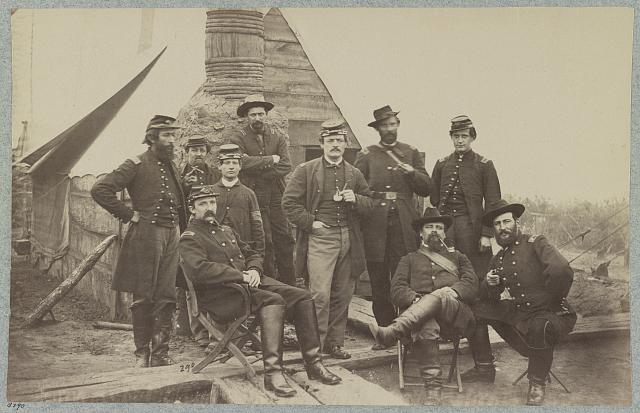

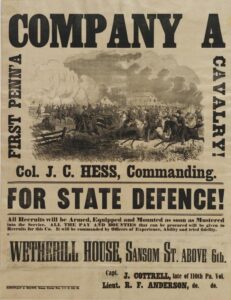

Philadelphia woefully lacked military preparedness when the war began. The initial rush of local volunteers, however, amply filled the quotas established by the federal government. Enlistees came from a variety of ethnic and social backgrounds. Most units, including thousand-man regiments, were formed by prominent citizens who recruited from their neighborhoods and towns or appealed to common ethnic ties. During the war nearly fifty infantry and cavalry regiments were recruited in the Philadelphia area, forty in New Jersey, and eleven in Delaware.

Many of the Philadelphia-area regiments—infantry, cavalry, and artillery—distinguished themselves during the war, and successful officers parlayed their military exploits and reputations into political careers. Philadelphia and its surrounding counties provided more than 100,000 men for the Union army: the city of Philadelphia (93,300), Bucks County (3,300), Montgomery County (3,900), Chester County (4,800), and Delaware County (1,900). New Jersey sent close to 80,000 men, and Delaware sent more than 12,000, most recruited from New Castle County.

Philadelphia played a major role in mobilizing for the war and providing relief for soldiers and their families. Drawing on their experience in social reform and charitable efforts, faith-based and other private organizations offered aid and comfort to soldiers and widows and orphans of soldiers. Among them, the nationally organized United States Sanitary Commission and the United States Christian Commission were the most prominent. Many northern cities organized fairs to fund these organizations by selling products, art, memorabilia, and other objects and charging admission. The largest such fair, held in Philadelphia’s Logan Square, June 7-28, 1864, was supported by the governors of the three contiguous states. Contributions by businesses, industries, and private citizens raised over $1 million in support of the Sanitary Commission.

Early Hopes for a Short Conflict Fade

In the wake of the Battle of First Bull Run (First Manassas) in July 1861, Philadelphians and their neighbors began to understand that the conflict would be long and potentially devastating. This realization, coupled with a series of morale-sapping setbacks in the eastern theater of military operations and mounting Union casualties, spurred open opposition to the war by southern sympathizers. Democratic newspapers pointed to the Lincoln administration’s inability to defeat the Confederate armies and condemned wartime measures such as the suspension of habeas corpus in many northern cites as examples of “tyranny.” The preliminary Emancipation Proclamation issued by Lincoln in September 1862 stirred further opposition to the war by peace Democrats in the region. Cries of Black-over-white and tyranny heightened with Lincoln’s signing of the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, and the call for African Americans to be recruited into the army. These reactions did not drown out jubilation by the Black population and other abolitionists, but anti-Lincoln sentiment deepened with the Enrollment Act of March 1863, which called for all able-bodied men, aged twenty to forty-five, to register for the draft. Many men in the region sought to evade conscription by paying a commutation fee of $300 or hiring substitutes. Conscription led to protests, defiance, and even violence in parts of Pennsylvania, especially in the anthracite coal region, but it helped to fill the ranks. Philadelphia escaped the protests and violent resistance that marked opposition to the draft elsewhere due to the presence of federal troops and the firm hand of the mayor enforcing law and order.

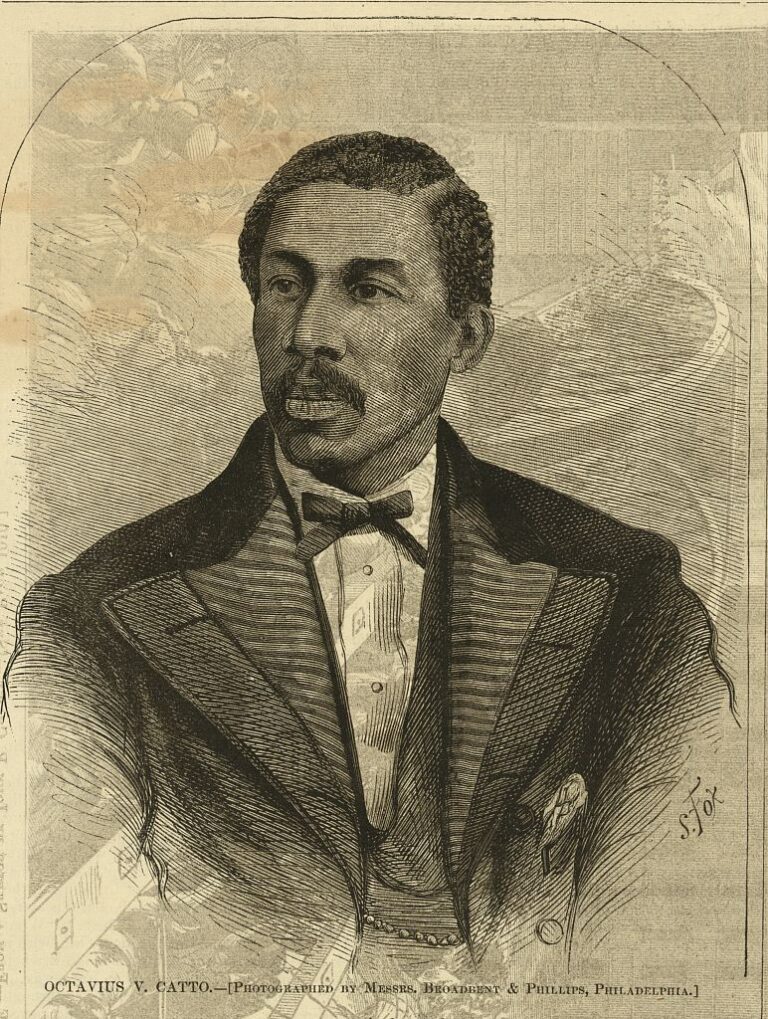

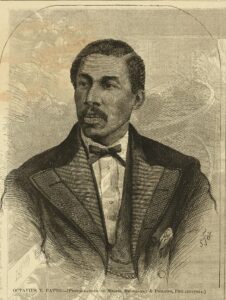

Needing manpower, the Lincoln administration sought to enlist Black troops. The president had been authorized to recruit African Americans as early as 1862, but he held off doing so for political reasons. Many white Americans believed recruiting Black soldiers was long overdue, for reasons of justice but especially to fill the ranks. Others held that Black men would make poor soldiers and would run away at the first shots of battle. Then, too, arming African Americans had the potential of making them equal to white men. When Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware initially balked at accepting Black recruits, many Black men from the region joined the few state-level Black regiments in service such as the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Infantry (commanded, as was every other Black outfit, by white officers). Despite the army’s efforts to limit their role in combat and often to confine them to fatigue or guard duty, Black soldiers from the Philadelphia area performed admirably during the war, and from that service called for the rights and respect due them as citizens. In Philadelphia, for example, Black soldiers and local Black women, angry over the inconvenience and disrespect of segregated public transportation there, pushed to end discrimination on the rails. After the war Black churches, veterans’ organizations, and social clubs played major roles in setting up and staffing schools for the “freedpeople” in the South, attacking racial discrimination in public services, and lobbying for the vote.

The reemergence of resistance to the Lincoln administration appalled Republicans in Philadelphia, most of whom viewed opposition to the war and calls for a negotiated peace as treason. To meet the threat of the “Copperheads,” as Republicans labeled northern opponents of the war, a group of prominent Philadelphians in November 1862 established the Union League to counter the Peace Democrats and reenergize support for the war. As one of its first acts, the league created a military committee to help recruit, organize, and equip regiments for the Union Army, including United States Colored Troops. The league also published tracts, posters, broadsides, and other printed materials and raised money to support the war effort, the Lincoln administration, and Republican policies during and after the war. The league’s example encouraged hundreds of such organizations to form across the North.

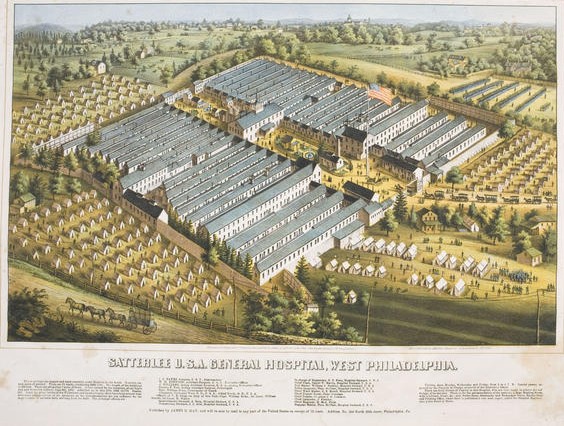

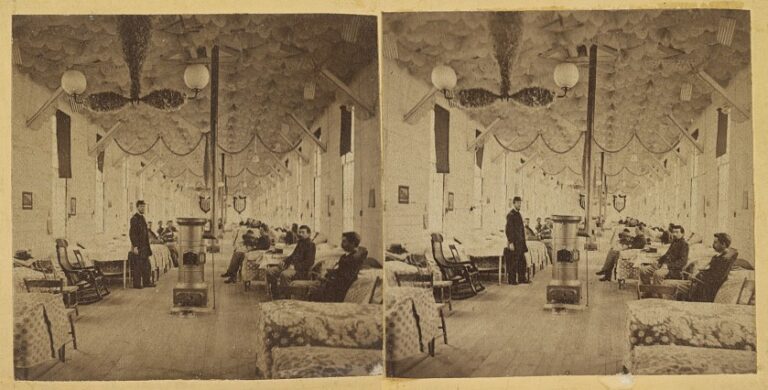

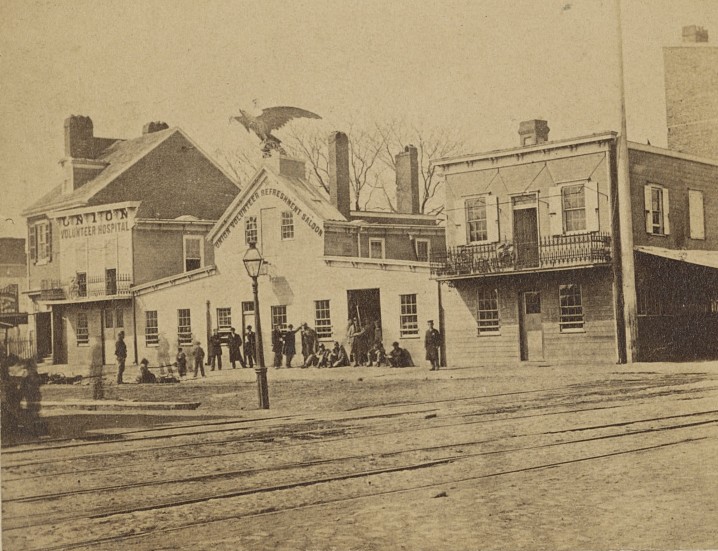

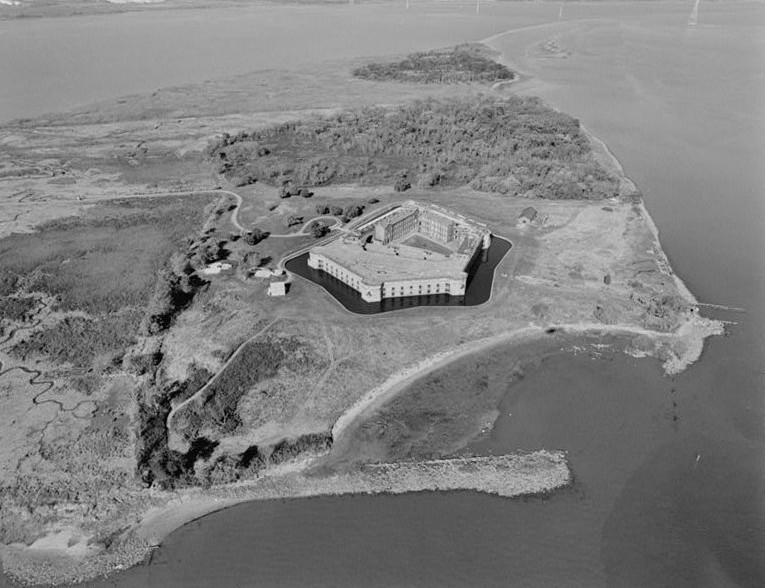

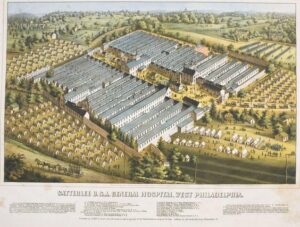

Philadelphia and the surrounding region supported the Union war effort in a variety of ways. The Frankford Arsenal supplied munitions; the Navy Yard built and repaired warships; and the DuPont Company in Delaware produced up to 40 percent of the black powder used by the Union army. The government also set up several military training camps in and around Philadelphia; the largest of which was Camp Cadwalader. And Philadelphia served as the northern station for receiving ships and contraband cargo seized in the blockade of the Confederacy. As the major railroad hub in the Mid-Atlantic region, Philadelphia maintained and supplied rail transport for soldiers and materiel; indeed, most Union soldiers from northern states east of the Appalachians who served in the eastern theater of the war passed through Philadelphia. This made the Philadelphia area a prime location also for wartime hospitals and refreshment stations.

New Efforts to Fund the War

Philadelphia also figured prominently in funding the war. Desperate to raise funds through bond sales, the Lincoln administration engaged Philadelphia financier Jay Cooke (1821-1905) to organize a major bond drive, which succeeded by pitching the purchase of the bonds not only to businesses but also to citizens as an investment in the nation. The mobilization of Philadelphia resources fostered a growing sense of national pride, purpose, and Philadelphia’s importance to the nation, which Republicans used to move the city firmly into its camp.

Wartime mobilization created jobs for men and women in the area’s many war-related industries. Men found jobs in manufacturing and services. Women often took over businesses and farms when their men went off to war, or they worked for pay as seamstresses making uniforms, clerks in government offices, and doing various tasks in munitions factories. Because of wartime inflation, workers’ pay did not keep up with the price of consumer goods, which led to workers protesting for more pay and better working conditions, although with mixed results.

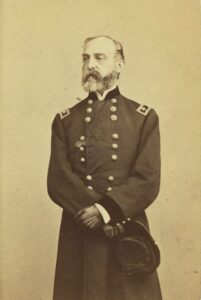

The war came to Pennsylvania in June 1863 when Robert E. Lee’s (1807-70) Army of Northern Virginia launched its northern campaign in hopes of defeating the Union Army on northern soil and dispiriting support for the Union. In Philadelphia fears of Lee’s army marching into the city led to panicky calls for militia and the digging of defenses. The anxiety subsided when the Army of the Potomac, commanded by native Philadelphian Major General George Gordon Meade (1815-72), defeated Lee’s army at Gettysburg (July 1-3). This victory, coupled with Major General Ulysses S. Grant’s (1822-85) capture of Vicksburg, Mississippi (July 4), led many to believe the war would end soon, but the worst of the fighting came the following year. In spring of 1864 Grant assumed command of all the Union armies, and Union armies hammered relentlessly at the Confederates on multiple fronts. General William T. Sherman’s (1820-91) army march through Georgia in late 1864 and the Carolinas in early 1865 helped secure Lincoln’s reelection in 1864 and raised Republican fortunes in Pennsylvania and elsewhere. The following year, Grant’s armies forced Lee’s surrender at Appomattox on April 9, and on April 26 Sherman received the surrender of General Joseph E. Johnston’s (1807-91) Army of Tennessee, effectively ending the military war in the East. In the western theater the last Confederate army surrendered in late May 1865.

The assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865, cut short the victory celebrations. Philadelphia and the surrounding region, like the entire the North, entered a period of mourning for the president, whose death soon became likened to martyrdom. The funeral train bearing the president’s body arrived in Philadelphia on April 22 enroute to its final resting-place in Springfield, Illinois. While Lincoln lay in state at Independence Hall, an estimated three hundred thousand mourners, who formed a line three miles long, waited up to five hours to pay their respects.

Adjusting to the War’s End

Although combat ceased with Union victory in 1865, the emotions it engendered continued as returning soldiers and their families and communities adjusted to resettling their lives, caring for the wounded, and remembering their service. The war also led to major efforts to define civil rights, not only for the newly freed people in the South but also for Black people in the North. Such efforts renewed political and social conflict in Philadelphia and its environs. An influx of Black migrants into the area heightened racial tensions, while competition for jobs and controversy over the Radical Republican program of Reconstruction led to violence.

After the war, Republicans tried to consolidate their wartime gains by continuing to promote business, financial reforms, tariffs, and other economic measures, and especially by seeking to secure basic civil rights for “freedmen” in the South and an orderly return of the former Confederate states to the Union. Trading on the memory of the martyred Lincoln, the Union victory, and the supposed “betrayal” of Democrats in their lack of full support for the war effort, and pointing to their economic policies, Republicans emerged as the dominant party in the Philadelphia and Pennsylvania and remained so well into the twentieth century. Democrats fared better in South Jersey and Delaware, where opposition to Reconstruction, especially resisting expansion of civil rights to Black people, played well in public and at the polls.

Remembering the war became an important part of adjusting to the postwar world. (Thousands of area soldiers died during the war, from disease to battlefield wounds, but no official count of casualties by county exists to know the exact numbers from the Greater Philadelphia area.) Cemeteries filled with Union soldiers marking their service. The national dedication of the Union cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, in November 1863, during which Lincoln delivered his Gettysburg Address, was part of a sustained national effort to memorialize the service of the soldiers. Local governments, church groups, ethnic associations, and other organizations put up statues, monuments, and memorials across the region. Philadelphia, for example, exalted its military leaders with statues of Pennsylvania native sons George B. McClellan (1826-85) and John Reynolds (1820-63) mounted on horses dominating the public square around City Hall and George Gordon Meade at the entrance to Laurel Hill Cemetery, where many Civil War veterans were buried. By some accounts, the Philadelphia region built more Civil War monuments and memorials than anywhere else in the North.

Tributes and Veterans Organizations Grow

Veterans also organized to lobby for pensions as well as public recognition. The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), established in 1866, became the nation’s most powerful veterans’ organization, wielding a political influence through the end of the century. At one time the GAR had fifty-six posts in the Philadelphia area and twenty-eight in South Jersey and twenty-nine in Delaware. Members had to have been honorably discharged from the U.S. Army, Navy, or Marine Corps; all were considered equal in the post hall, whether general officer or private soldier, including African American veterans. The organization advocated voting rights for Black veterans as well as patriotic education for schools. It helped found Decoration Day (later, Memorial Day), gained generous pensions for veterans, and staunchly supported the Republican Party. The first local Memorial Day ceremonies were held on May 30, 1868, in Doylestown, Bucks County, and at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia, hosted by General George G. Meade Post #1 of the GAR. By 1890, the GAR’s national membership exceeded four hundred thousand. Although its last surviving member died in 1956, the organization’s mission continued into the twenty-first century through the efforts of the Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War. Its museum and library in Philadelphia collected wartime memorabilia, printed material, military gear and uniforms, and more.

The Philadelphia region played a major role in mobilizing men and resources that brought Union victory in the Civil War and raised questions about the meaning of emancipation and freedom after it. Working in relief organizations encouraged women to push for political rights and larger roles in civic affairs. Some industries that scaled up demand to meet wartime needs continued to prosper, and improvements in chemistry, medicine, and engineering developed in Philadelphia during the war yielded postwar benefits. Philadelphia-area ties to the South continued after the war, with many women serving in freedmen’s schools set up by churches and philanthropic organizations and with renewed commercial connections, but Philadelphia was no longer a southern city. Its schools no longer enrolled many, or sometimes any, southerners, and its first families no longer enslaved people in southern places. The war consolidated Republican Party dominance in the region, and in Pennsylvania generally, though it did not weaken the Democrats altogether as their successes in local elections in the 1870s and after attested. The wartime generation also refused to forget the war or let those after them forget, as evinced in the monuments they constructed, the cemeteries they established, and the annual public invocations of soldierly valor and memory they celebrated.

Theodore Zeman, who earned his Ph.D. in history studying under Russell Weigley at Temple University, is Adjunct Professor of History at Saint Joseph’s University and at Penn State University Abington and the author of various studies of the Civil War era. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2025, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- Mob Scene at the Palmetto Flag (YouTube)

- Independence Hall and the American Civil War (National Park Service)

- John McCallister's Civil War: The Philadelphia Home Front (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- Civil War Soldiers and Sailors Memorial (Association for Public Art)

- Philadelphia in the Civil War (Digitized Book, Library of Congress)