Cycling (Sport)

By Vincent Fraley | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

The Philadelphia area’s connections to the sport of cycling have spanned nearly 200 years, reflecting its rise, decline, and resurgence in the United States. The region’s history of road, track, and all-terrain races began before the invention of the modern “bicycle” and continued into the twenty-first century with new variations of the sport and the annual Philadelphia International Cycling Classic.

Some of the earliest competitions in North America featuring two-wheeled, human-powered machines occurred in Philadelphia, where the French-invented “velocipede” became available to a limited extent in the early nineteenth century. Among the machine’s earliest American adopters was the artist and museum proprietor Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), whose sons and daughters informally raced “down hill like the very devil” on a 55-pound velocipede built by a Germantown blacksmith from a threshing machine. By the 1820s, however, the popularity of the velocipede faded in Philadelphia and in other American cities due to the machine’s expense and weight, lack of suitable roads, and harassment of riders by pedestrians and the public.

Philadelphia helped to set the stage for a new era of bicycle racing during the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, where the displays included a British-designed high-wheel, a bicycle with an extraordinarily large front wheel and a plate-sized rear wheel. With frames often made of iron supported by wooden or heavy rubber tires, the rider perched precariously several feet off the ground. A visitor to the fair, Albert Pope of Boston (1843-1909), was transfixed by the machine’s potential. A former Union Army colonel and manufacturer of air pistols and cigarette-rolling machines, Pope soon thereafter retooled his business and by the 1890s became one of the world’s largest manufacturers of bicycles.

A Sport Emerges

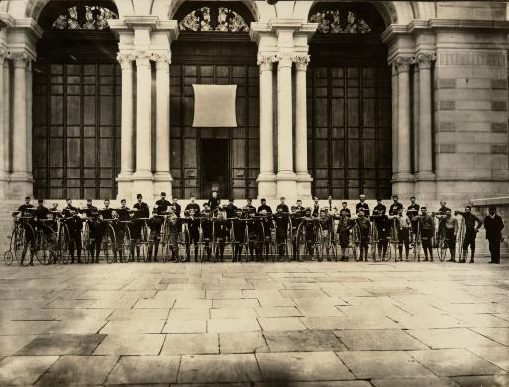

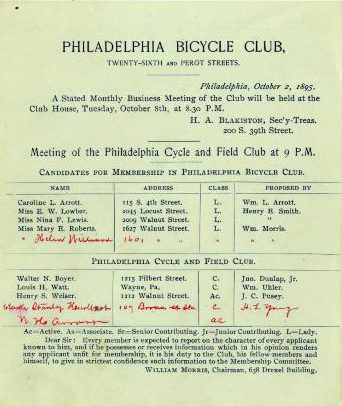

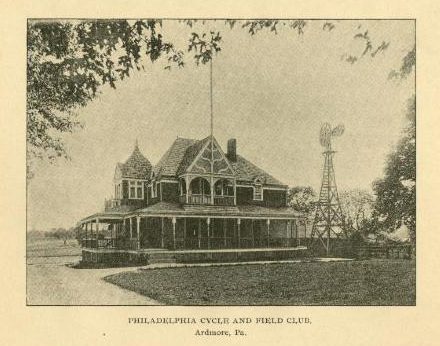

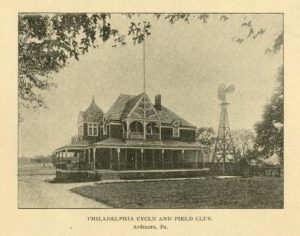

Cycling as a sport emerged in the era between the invention of American football (1869) and basketball (1891). Philadelphia’s first organized road races took place in the early 1880s, several years after the first formal bicycle competition in the United States (commonly believed to have taken place in 1878 in Boston). Philadelphia’s cyclists furiously pedaled the machines popularly called “ordinaries” in early road races sponsored by cycling clubs. These voluntary associations were formed by avid wheelmen–and in some cases by women–in cities and towns across the country. The Philadelphia Bicycle Club, the city’s oldest, appeared in 1879, followed shortly by Ardmore’s Cycle and Field Club and the Frankford Club. By 1891, these organizations had become so numerous in the Philadelphia area that a Handbook of Cycling Clubs became a practical publishing venture.

Racing in the early years demanded constant vigilance to avoid wagon wheel ruts, erratic ungulates, and edgy pedestrians crowding the primarily dirt and gravel roads. When not organizing and promoting races, many cycling clubs published advice on how to deal with these issues. “It is not always wise to dismount at once. To dismount suddenly is more likely to frighten a horse than continuing to ride slowly by, speaking to the horse as you do,” advised an 1888 Philadelphia Bicycle Club bulletin. “Foot passengers on the road should not be needlessly shouted at, but should always be given a good wide berth.”

To smooth out the issue of jagged roads, the League of American Wheelmen–cycling’s organizational booster–became an early advocate for new construction. The first state law legislating aid for road construction passed in New Jersey in 1891. Ostensibly intended to benefit carriages and horse-drawn streetcars, the improved road surfaces also became a boon to cyclists who sped to the Garden State for the annual twenty-five-mile run from Irvington to Millburn and other road races. Beginning in 1894, the New York Times Tri-State Relay linked New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania in a 150-mile race that began at the newspaper’s office in Manhattan and wended south through Trenton and Philadelphia before finishing in Riverton, New Jersey.

In addition to road racing, cyclists competed on tracks with smoother and safer surfaces. By the middle of the 1890s, an estimated one hundred dirt, cement, and wooden tracks dotted the country, including several in the Philadelphia area. Called velodromes, these tracks varied in distance, shape, degree of banking, and quality. Many wooden velodromes were temporary, constructed days before a race and razed thereafter from Logan Circle and other public spaces. Amateur and professional cyclists competed individually or as a team in sprint and endurance events.

Speed and Safety

During the final decade of the nineteenth century, improvements in bicycle technology together with manufacturers’ marketing campaigns spurred a bicycle mania and with it, expansion of the sport. Racing advanced from the “ordinary” to the “safety” bicycle. With their chain-drive transmission, pneumatic tires, and reduced height, safety bicycles allowed for greater speeds. By positioning the rider lower to the ground between two equal-sized wheels, the new machines reduced the chances of “taking a header” by vaulting over the handlebars during accidents, a common risk for “ordinary” cyclists.

At the zenith of the bicycle boom in the 1890s, cyclists competed for purses five times greater than the highest baseball player’s salary, and local and national newspapers detailed the styles and stratagems of professional “cracks” and “scorchers.” Interest in cycling spanned the globe, and in 1893, Camden-born Augustus Arthur Zimmerman (1869-1936) became the first American global cycling champion by winning the International Cycling Association’s inaugural world championship, held in Chicago to coincide with the World’s Columbian Exposition. Manufacturers of bicycles seized upon this broad public interest, developing marketing campaigns featuring product endorsements by prominent riders, a first in American athletics. Bicycle firms also pioneered in America the business practice of planned obsolescence on an industrial scale, whereby consumer goods are rendered obsolete shortly after being produced. For riders in the Philadelphia area, several dozen bicycle shops–including three located in the 800 block of Arch Street alone–hawked the latest frames, shoes, and other sundries.

Interest in cycling cut across racial lines, but for the most part, professional cycling mirrored prevailing racial tensions rather than surmounting them. Several state chapters of the League of American Wheelmen barred African Americans from joining, and white riders conspired to prevent Indiana-born Marshall “Major” Taylor (1878-1932), an African American and future world champion, from winning races. These incidents included a race at Philadelphia’s Woodside Track in 1897.

Female cyclists also enthusiastically adopted the sport as an engine of emancipation as well as competition. However, white male cyclists dominated professional racing and banned women from professional cycling in 1902 following the death of a female rider during a circus cycling performance. Philadelphian Margaret Longstreth Corlies founded the Sedgeley Club, an organization for women interested in cycling, canoeing, and skating, in the 1880s. By 1903, the year Sedgeley’s Boathouse Row clubhouse was completed, Corlies described Sedgeley as one of the world’s oldest athletic clubs for female cyclists.

Tests of Endurance

Through the 1890s and continuing into the 1920s, grueling and crash-ridden six-day races on tracks captivated cyclists and spectators. Limited to six days by laws that barred competitions on Sundays, the races had one simple rule: whoever covered the greatest distance in the allotted time won. The advantage went to the cyclists who could remain on the bikes the longest and sleep the least, shacking up in trackside cots and preparing food with portable stoves. Some cyclists used smelling salts and cocaine to remain awake and alert, leading to some of the earliest accusations of performance-enhancing chicanery. Crowds accumulated as the race wore on, producing a crescendo of cheer as the much-diminished pack of competitors completed their final laps 142 hours after the starter’s pistol rang out. Six-day races so tested cyclists’ physical and psychological stamina that New Jersey and other states attempted to intervene on humanitarian grounds to ban any cyclist from racing more than twelve hours per day (in New Jersey, the law did not pass).

In the years leading up to the Second World War, the popularity of professional cycling declined significantly. Interest in track and road racing waned during the Great Depression, and baseball emerged as the “national pastime.” The opportunity for achieving hitherto unheard-of speeds–which the bicycle gave athletes in the 1890s–shifted to the automobile. In the Philadelphia area, as in the rest of the country, cycling became a specialized sport enjoyed by a narrower audience, and the bicycle became primarily associated with recreation and transportation.

Public interest in cycling resurged following stunning American victories in the 1984 Olympics and the winning of the 1986 Tour de France by California native Greg LeMond (b. 1961), the first non-European to don the coveted yellow jersey. Philadelphia became the site for the CoreStates USPRO Championship, which began in 1985 and developed into one of the most prestigious single-day races in the Western Hemisphere. Conceived as a national professional road race, at 153 miles it was the longest single-day race in the United States. Continuing annually and winding through several neighborhoods, including Roxborough, East Falls, and Lemon Hill, the race made famous the “Manayunk Wall,” where thousands of spectators lined Lyceum Avenue to watch cyclists ascend the 285-foot climb with a 17 percent grade at its steepest segment. Within a decade, the popularity of the race inspired other professional road races in several states. By 1992, the event was a part of the Triple Crown series that included the CoreStates USPRO, the Thrift Drug Classic in Pittsburgh, and the Kmart Classic in West Virginia. In 2013, the rebranded Philadelphia International Cycling Classic was shortened to 110.7 miles. Amateur and professional female cyclists from around the world also traveled to Philadelphia from 1994 to 2012 for the Liberty Classic, held simultaneously with the men’s race. The event became part of the Union Cycliste Internationale’s Women’s World Tour in 2015 and continued to draw the sport’s premier professional female cyclists.

Philadelphia also became a center for cyclocross in 2013, when the city hosted the Singlespeed Cyclocross World Championships in Fairmount Park. Originally developed as a way for road racers to train during the fall and winter, cyclocross incorporates paved and off-road surfaces and obstacles that require cyclists to dismount and carry their bicycles. With the presence of heckling spectators, varied terrain, and other impediments, cyclocross resembled the conditions of the earliest bicycle racing. Series of races have been sponsored across the region by PACX (Pennsylvania Cyclocross) and MAC (Mid-Atlantic Cycling).

Interest in velodromes also resurfaced in 2015, when the advocacy group Project 250 proposed a $100 million Olympic-sized, 6,000-seat velodrome for South Philadelphia’s FDR Park as part of the organization’s plan for new sustainable, mixed-use facilities. Philadelphia’s Commission on Parks and Recreation rejected the proposal, saying that it did not meet the standards of the city’s Open Land Protection Ordinance. In 2016, more than two dozen velodromes actively hosted races in the United States, including the Lehigh Valley’s Preferred Cycling Center in Breinigsville, Pennsylvania, and the Garden State Velodrome in Monmouth County, New Jersey.

Nearly two hundred years after Charles Willson Peale’s children raced on one of the few velocipedes in North America, the Philadelphia area’s captivation with cycling continued. Through the International Cycling Classic and Singlespeed Cyclocross World Championships, Philadelphia and the surrounding environs remained a hub of the sport’s amateur and professional athletes in the twenty-first century.

Vincent Fraley is communications manager for the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and writes the Philadelphia Inquirer’s weekly history column, Memory Stream. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Manayunk cycling community reacts to 2013 bike race cancellation (WHYY, January 22, 2013)

- The financial challenges of hosting a cycling event in Philadelphia and beyond (WHYY, January 25, 2013)

- Manayunk and Roxborough residents weigh the pros and cons of hosting the Philly Cycling Classic on The Wall (WHYY, March 29, 2013)

- Philly Cycling Classic organizers strive for 'classic European' style race (WHYY, April 8, 2013)

- Manayunk native included in Philly Cycling Classic lineup (WHYY, May 30, 2013)

- Pro cycling coming back to Delaware for Wilmington Grand Prix (WHYY, February 12, 2014)

- Your guide to the 2014 Parx Casino Philly Cycling Classic (WHYY, May 29, 2014)

- Delaware added to USA Cycling tour (WHYY, March 23, 2016)

- Philly pro cycling race down, but not completely out yet (WHYY, January 27, 2017)

Links

- The Bicycle Club of Philadelphia

- Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia

- Delaware Valley Bicycle Club

- Sturdy Girl Cycling

- The Sedgeley Club

- League of American Cyclists

- Manayunk Wall: The Climb Every Racer Knew (Velonews)

- Chronology of the Growth of Bicycling (International Bicycle Fund)

- How We Ride (National Museum of Play)

- Manayunk bike race is off: 2017 Philadelphia Cycling Classic takes a break (BillyPenn.com, January 27, 2017)