Deindustrialization

By David Elesh

Essay

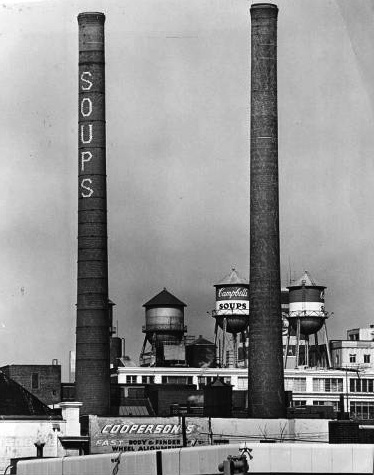

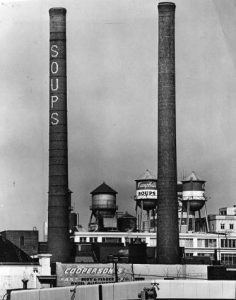

The Philadelphia region’s long-held reputation as the “workshop of the world,” though richly deserved, did not prevent it from suffering the same loss of manufacturing firms and jobs that devastated the economies of other manufacturing centers. Local products ranged widely, from locomotives and ships to silk hosiery, wool carpets, machine tools, hand tools, lighting fixtures, steel, soup, and men’s and women’s apparel. With the exception of a limited number of large companies such as Baldwin Locomotive, Campbell Soup, Cramp Shipbuilding, and Midvale Steel, most regional manufacturers were small- and medium-sized firms that specialized in customizing their products to consumers’ needs. Yet neither the diversity and quality of products nor the flexibility of their makers checked the region’s deindustrialization. The causes and pacing varied by industry, location, and time period, but after World War II the region saw its share of jobs in manufacturing decline more rapidly than the nation’s.

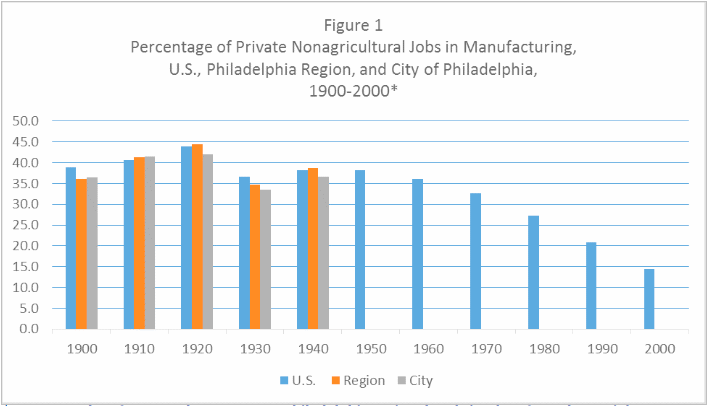

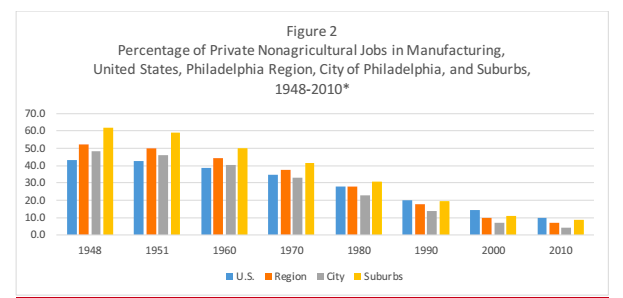

Using the percentage of private nonagricultural jobs in manufacturing as an indicator, deindustrialization began in the nation, city, and region about 1920; however it proceeded at different paces in Philadelphia and its suburbs. The city reached its largest number of manufacturing jobs in 1920, although the peak did not occur in its suburbs (Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery Counties in Pennsylvania and Burlington, Camden, and Gloucester Counties in New Jersey) until about 1950. In part, city firms moving to the suburbs helped sustain manufacturing jobs in the wider region. The region’s deindustrialization after 1920 corresponded to the national trend that–allowing for the aberrations created by the Great Depression and World War II–followed a relatively constant downward slope. Deindustrialization thus began even before concern arose about either competition from foreign companies or outsourcing by U.S. companies.

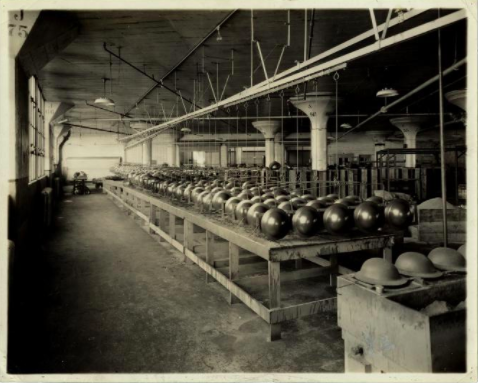

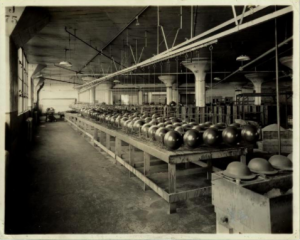

The causes of the decline in manufacturing’s share of the workforce varied by time period, geography, and industry. Throughout the twentieth century, technological improvements–often driven by the desire to lower labor costs–permitted manufacturers to increase production with the same or fewer workers. These changes were both organizational and mechanical. At the beginning of the century, Frederick Taylor (1856-1915) at Bethlehem Steel, Link Belt Engineering, and Cramp Shipyard and Charles Bedaux (1886-1944) at Campbell Soup analyzed and reshaped workers’ actions to maximize productivity at the lowest cost under the rubric of “scientific management.” These efforts often merged with the growing popularity of continuous-flow assembly line production, exemplified by Ford’s Philadelphia automobile plant (opened in 1914), and developments in technology such as the spread of electric power, new tools such as the saber saw (replacing shears) in the ready-to-wear apparel industry, and linked conveyor systems in food processing. These new technologies increased the efficiency and volume of production, but their costs also required manufacturers to expand their sales and devote ever greater efforts to marketing their products to recoup their investments. The greater costs increasingly led manufacturers to purchase engineering, advertising, accounting, legal, financial, public relations, and other support services from outside companies. Yet, both nationally and locally, until the Great Depression the number of production jobs in manufacturing grew even as their percentage of all jobs shrank, outpaced by the growth in nonmanufacturing employment.

The Great Depression and World War II

The Great Depression hit small- and medium-sized manufacturing firms like most in Philadelphia with particular severity. In the core city and regional industry of textiles, for example, many Philadelphia manufacturers became increasingly fragile financially as the boom of the 1920s came to a close. Their profits had been diminishing, hurt by the growing power of chain retailers to demand goods at a set wholesale prices, by the competition created as consumers turned to simpler and cheaper woven goods, and by overproduction, especially in hosiery. In 1928, Philadelphia had 850 textile firms, 350 of them in the Kensington neighborhood, and employed nearly 35,000. By 1935, a study of eighty-two of those firms found that 30 percent had closed or moved, with a loss of 8,700 jobs. In carpet-making, the city had 9,500 jobs in 1925, but just 42 percent remained by 1934. And of 17,691 hosiery jobs in 1935, only 40 percent remained six years later.

Meanwhile, federal programs during the Depression tended to favor economic development not in the Northeast but in southern and western states, where the New Deal of the Roosevelt administration created jobs through investments in infrastructure. The Public Works Administration and the Works Progress Administration built roads, bridges, viaducts, dams for electrical power, water systems, schools, hospitals, and other improvements. These projects changed the quality of life in entire regions, providing a base for the investments in manufacturing the federal government made to fight World War II and attracting private investments. After the war began, the rapid expansion of manufacturing on the West Coast and military bases in the West and South stimulated relocations to these areas and laid a foundation for postwar migration and further economic development.

For eastern producers such as those in Philadelphia, the war helped equip new competitors with the latest technology, lowered transportation costs to many markets, and often reduced labor costs. Although southern states had sought to lure manufacturers since the 1930s with cheap labor, low taxes, subsidized construction costs, and other inducements, these efforts intensified and found greater success in the postwar period. Taken together these factors meant that plants in southern and western cities were going to take business from their eastern and midwestern rivals. After World War II, such emerging competition proved particularly difficult for the Philadelphia region because of its heavy reliance on manufacturing in both the city and suburban economies.

Furthermore, the Philadelphia region risked losing jobs because much of the diversity of its manufacturing base concentrated in the production of nondurable goods (like clothing, magazines, food, and shoe polish), which were more susceptible to competitive pressures than durable goods (like machinery, automobiles, washers, and hand tools). In 1948, 31 percent of Philadelphia’s privately employed labor force worked in nondurable manufactures, compared to only 19 percent for the country as a whole. Manufacturing nondurable goods often took place in small establishments, required less capital investment, demanded less-skilled workers, and paid lower wages. Less dependent on a large investment in plant and equipment, companies manufacturing nondurable goods could be more easily relocated than more capital-intensive durable-goods manufacturers. The lower wage structure of nondurable firms also encouraged them to seek locations with cheap labor.

Changing Technologies and Markets

Philadelphia firms also faced technological and market changes that reshaped plants and whole industries in ways that further encouraged moving factories from the city to outlying areas. Existing factories became outmoded because production technologies increasingly required more open space on one floor. Ford built a multistory plant at Broad and Lehigh Streets in Philadelphia in 1914, but in 1926 the company moved to Chester, Delaware County, to take advantage of efficiencies that could be achieved with continuous-flow assembly line production in a new one-story plant. Similarly, Baldwin Locomotive found it increasingly difficult to produce the larger and more powerful locomotives demanded by its customers in its site in the city’s Spring Garden neighborhood and began building a new plant in suburban Eddystone in 1906. Aside from its production problems, Baldwin faced serious competition from the American Locomotive Company (ALCO), created in 1901 by the merger of some of its former partners, whose combined sales totaled 45 percent of the market.

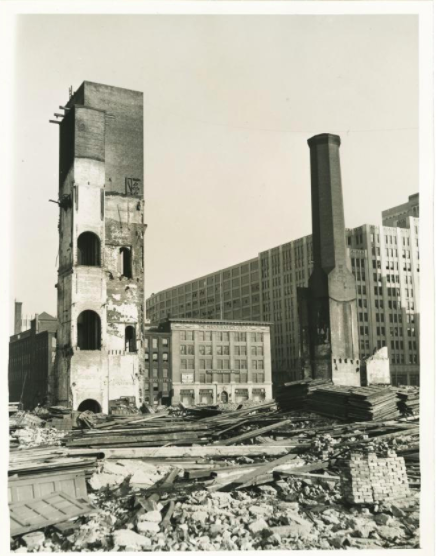

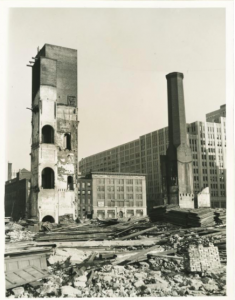

Baldwin’s record year probably marked a turning point in prosperity for both the company and the railroad industry. During the more than twenty years it took Baldwin to complete the Eddystone plant, its market matured and began to fade as trucks became a growing competitor. By 1920, a million trucks were transporting goods on American roads. Between 1900 and 1910, the number of locomotives on American rails rose 59 percent, but between 1910 and 1920, that total grew just 15 percent, and between 1920 and 1930, railroads began a seven-decade decline. Making matters worse, Baldwin was slow to shift to the more efficient diesel electric engine. The company closed its Philadelphia plant in 1928, entered bankruptcy in 1935, emerged from it in 1938, and hobbled forward under several reorganizations and mergers with companies headquartered elsewhere until 1972. But the Eddystone facility had ceased production in 1956.

A changing market also claimed the Stetson Hat Company. Started in nineteenth-century Philadelphia, Stetson became one of the nation’s largest makers of fashionable men’s hats as well as its iconic cowboy hat during the 1920s. But after World War II, men outside the West gradually stopped wearing hats. Stetson closed its factory in the city’s Kensington neighborhood in 1971, although it continues to produce cowboy hats in Texas.

For other companies, the rise of continuous-flow production technologies, the large single-floor spaces they require, and the lower costs of suburban land contributed to decisions to suburbanize wholly or partially. Westinghouse Electric, Ford Motor, and Rohm and Haas were among the firms that made that choice in the first quarter of the century. Other firms–such as Chester County’s Lukens Steel and American Viscose (at one time the world’s largest producer of rayon) and Montgomery County’s Lee Tire and Alan Wood Steel–started in those suburban areas.

The Triumph of Synthetics

Some Philadelphia industries simply lost viability over time. Prior to the Depression, textile manufacturing was a major industry in both the Greater Philadelphia area and New England. But New England’s manufacturers were far more concentrated in cotton textiles and more susceptible to competition from lower cost southern producers that began to emerge in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By the 1920s, New England producers were closing or investing in southern plants. In contrast, the diversity of the Philadelphia area’s producers delayed their decline.

Although the Philadelphia region’s textile firms outlasted New England’s, their fortunes changed for the worse after World War II. Many of these companies produced silk or rayon hosiery that was quickly supplanted by lower-cost nylons after the war. Not only was silk a significantly more expensive raw material, nylon offered a further cost advantage because Dupont, nylon’s inventor, produced both the fiber and the finished product. Most silk firms, lacking capital to convert to the new machines, needed to knit nylon and simply closed.

Other Philadelphia area firms led in the production of wool carpet yarns and woven wool carpeting, successful industries until the invention of inexpensive nylon tufted carpeting in 1950. Developed in Dalton, Georgia in the 1930s, tufting arose from mechanizing the production of cotton chenille bedspreads. Its inventors quickly thought to adapt the technology to carpeting, but their efforts were unsuccessful until nylon became available after the war. The technology developed in the South for making and dyeing the new yarns and the new carpeting was completely different, and few wool carpet firms made a successful transition. By 1955, the market for wool carpeting essentially collapsed, and carpet production shifted southward–often to Dalton. By the early twenty-first century, less than 2 percent of the market for carpeting was woven wool.

Synthetic materials also led to the closing of American Viscose in Marcus Hook, Chester County. As the market for rayon in apparel declined in 1930s and 1940s, the company succeeded in making cording for tires until 1954 and cellophane for some years afterward. But nylon, polyester, and acrylics eventually proved superior for both cording and wraps; the plant shut down in 1977 with a loss of 580 jobs.

Responses to Growing Labor Militancy

From the late 1930s into the 1950s, Philadelphia’s labor climate also significantly changed, inhibiting new investment in the local textile industry. A long and bitter strike against Philadelphia’s Apex Hosiery Company in 1937 opened a decade of rising labor militancy across the regional economy. Reaching a crescendo with strikes against Baldwin Locomotive, Westinghouse, and General Electric in 1945-46, workers’ militancy contributed to shifts of production and investments to the nonunionized parts of the region and country in the 1950s and 1960s.

These local strikes echoed national trends in management-labor conflict, but they had particularly significant effects on Philadelphia’s postwar textile industry because the timing coincided with rapid changes in technology and products. In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the industry reached a critical transition: new products had to be produced from new materials in new ways in new plants. Factory owners confronted the question of whether to build new plants in the Philadelphia metropolitan area, close, or shift production elsewhere. When they had a choice, they typically moved elsewhere or diverted their capital to other types of investments.

Emergence of Foreign Competition

Even when Philadelphia manufacturers successfully adapted to changing technologies and markets, low-cost foreign competition often took a toll. The knitwear industry, for example, had always used machines more intensively in its production than other apparel manufacturers, and it therefore withstood competition from lower-wage sites until the 1970s. Up to that point, employment actually expanded as the industry adapted by switching to synthetic yarns, specializing in highly styled women’s wear, integrating subcontracting into one organization, investing in new plants and equipment, and selling directly to retailers. Eventually, however, Asian firms, using profits from the low-margin knitwear that domestic manufacturers could not profitably produce such as T-shirts, along with reductions in tariffs on imported goods, moved to compete at the high end of the market as well. Starting in the 1970s, Philadelphia’s knitwear manufacturers began disappearing.

Throughout the 1950s and most of the 1960s, other apparel employment remained relatively stable in the face of rising competition from southern, western, and offshore producers. Philadelphia’s concentration on the production of men’s and boys’ clothing, less vulnerable than the larger and more competitive market for women’s clothing, may have helped protect the industry. Because of the greater standardization to men’s and boys’ clothing, machines could be employed more extensively in its production, making it somewhat less sensitive to labor costs. By the late 1950s, however, foreign competition in men’s apparel had become a significant problem and by the early 1960s, an imported sport coat could be purchased at retail in a department store for the cost of production to a Philadelphia manufacturer. In addition, producers increasingly complained of being unable to find needed space for expansion within the city at affordable rents, and they worried about a critical shortage of skilled labor. Despite some city, state, and union efforts to aid the industry, the manufacture of clothing began a universal decline in the 1970s as production shifted offshore.

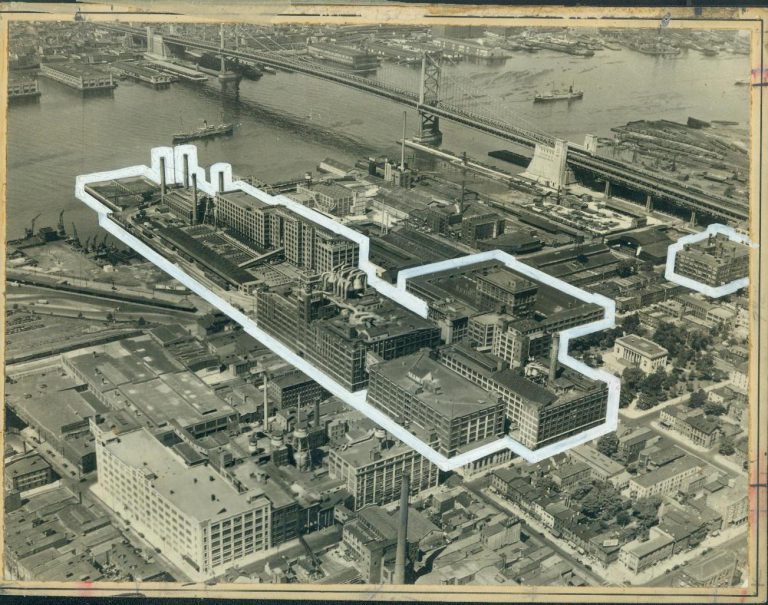

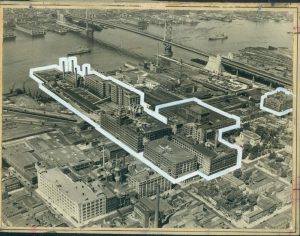

Competition facing urban manufacturing plants could also be internal, as companies expanded production by adding newer, more automated facilities in other locations. In 1990, Campbell Soup closed its antiquated Camden soup plant with a loss of 940 jobs because its three remaining newer soup plants could supply its worldwide markets at lower cost. However, Camden remained the company’s world headquarters, illustrating the historical pattern of dwindling numbers of production jobs supporting relatively constant or expanding numbers of marketing and administrative positions.

Although the region’s postwar presence in durable goods manufacturing lasted longer than in nondurable goods, many of the same forces were at work. A new regional steel producer, USX’s Fairless Hills plant in Bucks County, opened in 1952 using a traditional open hearth system just as steelmaking began to shift to newer basic oxygen processes. The newer technology reduced capital costs, improved productivity, and afforded lower pricing, but USX and Bethlehem Steel, the nation’s largest producers, did not begin to adopt it until the mid-1960s, allowing significant competitors in both the U.S. and abroad to emerge. Although Fairless Hills had employed as many as ten thousand by 1974, only 850 jobs remained when it largely closed in 1991. The closure of its cold rolling and tin mills in 2001 left just 250. Other steelmakers also struggled. Lukens Steel, a specialty producer in Chester County, and Alan Wood Steel in Montgomery County, underwent ownership changes, mill closures, and job losses until their acquisition in 2006 by ArcelorMittal, the world’s largest steel company, Indian-owned and headquartered in Luxembourg.

A similar pattern led to the closing of Lee Tire in suburban Montgomery County. Michelin Tire introduced the radial tire in France in 1948, and its use spread rapidly in Europe and Asia. Relative to the existing bias ply tires, radials offered at least twice the tread life, better handling, and better mileage. American manufacturers, including Lee, resisted adopting the new technology because it required new tire-making machines. Although they purchased licenses to make radial tires from Michelin, American tire companies did not succeed in making a satisfactory product until years after 1968, when Ford became the first American car manufacturer to offer radials (Michelins) as standard equipment on a car. In 1966, Lee was sold to Goodyear and it closed in 1980.

In the second half of the twentieth century, the cumulative effects of three developments, one in transportation, one in retailing, and one in communication, dramatically affected manufacturing in the nation and the Philadelphia region. In transportation, the shipping container, a forty-foot-long steel box into which producers pack their products, revolutionized shipping. Invented in 1956, containers reduced shipping costs by facilitating automated cargo handling and massively reducing pilferage. Easily transported on trucks, railcars, and ships, the “box” dramatically reduced the ability of domestic manufacturers to compete with foreign producers and cut the geographic advantage that had protected high-cost domestic manufacturers against lower-cost domestic competitors. Its success put additional pressure on the region’s small- and medium-sized manufacturers.

In retailing, the rise of Walmart as a national company during the 1970s reshaped manufacturing and retailing. Walmart’s policy of purchasing only directly from manufacturers removed the costs of dealing with wholesalers and pressured manufacturers to compete by offering the lowest prices. Walmart’s consolidation of legal, accounting, banking, advertising, printing, and marketing at its Arkansas headquarters hurt both local manufacturing and service businesses. For example, Philadelphia printers –commercial printing is a type of manufacturing – who make marketing materials for local retailers lost out from both the transfer of that business elsewhere and the closure of other local retailers unable to compete with Walmart’s prices. Its strategy of “everyday low pricing” pushed suppliers to constantly lower costs or lose out to a lower-priced competitor (pressure similar to what Philadelphia textile makers had faced in the 1920s). Eventually, this led manufacturers to move production to where labor costs were lower. But establishing factories in foreign countries also transferred knowledge of how to make products to foreign countries, creating foreign competitors. Large American retailers either followed the Walmart model or found their markets evaporating. American manufacturers who did not move production abroad either slowly disappeared or were forced to seek niches where they could survive.In communication, the rise of the internet made Amazon and other online retailers possible. Amazon, building on the prior two developments, showed that it was possible to remove the cost of the brick and mortar store from consumer prices. Amazon also intensified the pressure on manufacturers to constantly reduce prices, adding to the winnowing of manufacturing.

By the early twenty-first century Amazon and Walmart exemplified the global consolidation of economic enterprises seen in the region’s manufacturing. An Indian company owned the region’s largest remaining steel producers, and a Norwegian company in partnership with the city and U.S. government owned its remaining shipyard. The world’s sixth-largest pharmaceutical and medical instrument company, GlaxoSmithKline, resulted from a merger of Philadelphia’s premier pharmaceutical and medical instrument manufacturer, SmithKline Beecham, with London-based GlaxoWellcome. Such consolidation in an industry tended to reduce competition, create barriers to entry, raise prices, diminish innovation, and inhibit wage growth of production workers. Workers in one of a company’s sites could find themselves competing against workers in another, with the losers often facing plant closure.

The Twenty-First Century

In the twenty-first century, manufacturing in the region and nation continued to slip. In 2010, manufacturing accounted for just 6.7 percent of all jobs in the Philadelphia region. Despite political promises to rebuild the nation’s manufacturing base, there was little reason to believe that manufacturing’s share of jobs in either the national or regional economies would materially improve, even though the total value of U.S.-manufactured goods continued to rise. Throughout the history of manufacturing newer industries tended to employ more automation than older ones, and each cycle of investment in existing industries typically replaced more workers with machines. This occurred not only in the United States but also in the countries to which American firms exported production. Because each cycle of investment required greater skills on the part of production workers, they continued to command good wages. But manufacturing supported a diminishing share of households.

The decline of manufacturing often devastated neighborhoods and communities in areas of the Philadelphia region where it has once thrived. Kensington and the suburban city of Chester were illustrative. As plants in Kensington closed, house values plummeted, making it difficult—if not impossible—for workers who owned their own homes to sell and move to places with better job prospects after plants closed. Community shops failed, banks closed, churches and schools declined, and services deteriorated. Over time, the real estate market collapsed and houses that could not be sold became abandoned. As poverty rose, crime and other social problems increased. Outside Philadelphia, smaller municipalities experienced similar but usually more severe consequences because they rarely had the resources of larger, more diverse cities. Decline often followed loss of one or two large employers such as Ford and Sun Shipbuilding in Chester or RCA Victor and New York Ship in Camden.

Yet the abandoned factories could also hold the potential for a renaissance. In the 2010s, several city neighborhoods once dominated by factories have experienced a renaissance, perhaps fragile, through waves of small business entrepreneurship (especially in services), the in-migration of empty-nest couples, and the desire of young adults to live in the city. Thus Manayunk, Northern Liberties, and sections of Kensington and South Philadelphia became magnets for housing rehabilitation and restaurant startups. Several former regional “manufacturing suburbs” (Downingtown, Phoenixville, Glassboro) began to follow suit, but others (Bristol, Camden, Chester) found it difficult to counter deindustrialization’s pervasive effects. New chapters in their stories remained to be written.

David Elesh is emeritus faculty in sociology at Temple University. He has written widely on industrial change and its consequences. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Another fire strikes former industrial building in Camden (WHYY, July 6, 2011)

- Kids in a Germantown piano factory (WHYY, July 28, 2011)

- Mt. Airy residents tackle abandoned buildings during city-wide cleanup day (WHYY, April 16, 2012)

- Globe Dye Works cast as venue for ambitious sculptural installations (WHYY, September 10, 2012)

- Wissahickon civic delays vote on proposal to convert vacant factory site into Main Street apartments (WHYY, October 3, 2012)

- Plans to convert shuttered Wayne Junction factory into daycare leave neighbors concerned (WHYY, May 29, 2013)

- Former Germantown industrial site to house community preservation initiative (WHYY, October 8, 2013)

- Calls continue for EPA cleanup in Kensington area with elevated lead levels (WHYY, October 14, 2015)

- Progresso Soup factory in Vineland might close (WHYY, July 21, 2016)

Links

- Broad and Lehigh's Landmark Botany 500 Building, Awaiting Its Next Life (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Stetson Hats: Western Icon Made Here (PhillyHistory Blog)

- PhilaPlace: Stetson Hat Company Site (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Zophar, Tran, And The Chocolate Factory (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Life and Death of Callowhill (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Industrial Bones Of South Philadelphia (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- With Both Expanding, Can Recreational And Industrial Uses Coexist On The Delaware? (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Washington Avenue: A Representative Example of Philadelphia’s Industrial Past, Part I (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Frankford’s Fate in Post-Industrial Philadelphia (PhillyHistory Blog)

- In the Heart of Philadelphia’s “Lead Belt” (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Roots of Hypersegregation in Philadelphia, 1920-1930 (PhillyHistory Blog)

- PhilaPlace: The Sugar House (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Curtis Publishing Plant (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Cramp Shipyard — “A Community Organization and a Community Institution” (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)