Fabric Row

Essay

A textile and garment district emerged during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries on South Fourth Street, between Catharine and Bainbridge Streets in South Philadelphia, as immigrants transformed the neighborhood into a Jewish Quarter. Fabric businesses survived the Great Depression and remained prosperous for more than a century, employing generations of garment workers. Some shops continued to be active in the twenty-first century in the district that became known as Fabric Row.

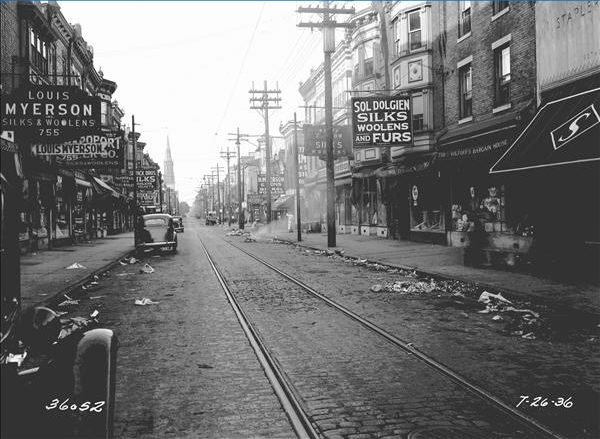

In the 1880s, as part of a widespread and varied wave of immigration to the United States, Philadelphia became home to a large number of Eastern European Jewish newcomers. The Jewish population increased significantly in 1905, when nine thousand Russian Jews arrived in Philadelphia following renewed pogroms against them in Russia. Moving into areas that later became known as Queen Village and Society Hill, these waves of immigrants created a “Jewish Quarter” extending from Spruce Street in the north to Christian Street in the south, between Third and Sixth Streets. Fourth Street became the core of the Jewish community, while the perpendicular South Street became a diversified hub for immigrants of other ethnicities. Starting in the late nineteenth century, Fourth Street became known as “Der Ferder,” meaning “the fourth” in Yiddish, and began to fill with fabric and garment-related trades.

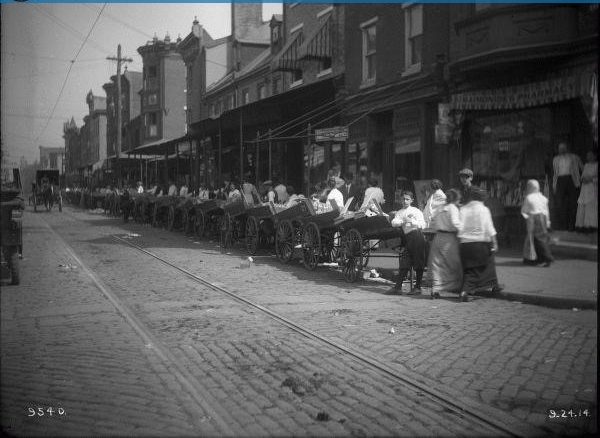

Initially, many immigrants worked as tailors or seamstresses in sweatshops or did sewing work at home, but during the first half of the twentieth century they also transitioned to peddling fabrics, dry goods, and produce from knapsacks or at curbside stands made from boards and sawhorses. The most prosperous peddlers sold goods from pushcarts, for which licenses could be purchased for $5 from City Hall. By 1906, immigrant entrepreneurs operated hundreds of pushcarts on South Fourth Street between Lombard and Carpenter Streets. Peddlers who could not afford to buy pushcarts had the option to rent them from wealthier businessmen who purchased licenses in bulk and rented them out for 25 cents per day or $1.50 per week.

Many fabric businesses on Fourth Street started as curbside stands or pushcarts, then moved into storefronts. Families played important roles in establishing and sustaining these businesses for decades. For example, Abraham Marmelstein (1891-1969), a Polish immigrant, entered the fabric industry in 1919 as a peddler selling needles and thread door-to-door. Eventually, he purchased a pushcart and later, in 1937, a three-story row house on Fourth Street where he lived and ran his business with his wife, Dora (1896-1979), and family. The business passed down to succeeding generations, remaining in operation until 2015. Other family businesses—Paul’s, Maxie’s Daughter, and Albert Zoll’s, among others—followed a similar pattern. South Fourth Street became dominated by fabric- and garment-related trades (textiles, bridal, drapery, wallpaper) but also included kosher butcher shops and other grocery-related food shops (vegetable and fruit stands, fish and meat markets). The Famous Fourth Street Delicatessen, which opened in 1923 at Fourth and Bainbridge Streets, became a symbol of Jewish culture and prosperity, featured in films such as Philadelphia (1993) and In Her Shoes (2005).

As it grew, the Fourth Street business community weathered and responded to world events. In 1905, thousands of people marched on Fourth Street in mourning for the victims of the pogroms against Jews in Russia. In 1918, the worldwide influenza epidemic hit densely populated areas like Fourth Street especially hard. Many businesses voluntarily closed and helped distribute food and supplies to the needy. During the Great Depression (1929-41), fabric businesses on Fourth Street remained prosperous because people who could no longer afford to buy ready-made clothing from department stores purchased fabric to sew their own garb. Nevertheless, in 1933 merchants formed the South Fourth Street Business Men’s Association in to promote continued trade and address issues such as street sanitation, police security, and hours of operation.

The Second World War and its aftermath brought new challenges to Fourth Street. During the war, merchants found it difficult to keep their stores stocked as manufacturers constantly supplied the armed forces. To conserve electricity, all stores on Fourth Street closed early on Tuesdays and Thursdays. After the war, postwar trends of consumerism and movement from cities to suburbs added to the challenge. As demand for fabrics shifted to décor for new suburban homes, Fourth Street merchants adapted their merchandise to offer goods such as ready-made curtains. Some of the merchants themselves moved to the suburbs, still running their businesses on Fourth Street but no longer living above the store. With the increase of automobiles and demand for parking spaces, in 1955 a city ordinance brought an end to an era by banning pushcarts from Philadelphia streets.

Some Fourth Street businesses expanded to the wholesale market. Fleishman Fabrics & Supplies, which opened in 1923, started as a men’s fabric wholesaler while also keeping a room devoted to menswear fabric for suits. Other businesses formed wholesale divisions, including Winitsky and Company (Win-Tex Fabrics) and Rosenblitt’s Fabrics (Rose-Line). When Rosenblitt’s was taken over by the founder ’s grandson, Jay Adler, it continued to operate on Fourth Street as Adler’s Fabrics.

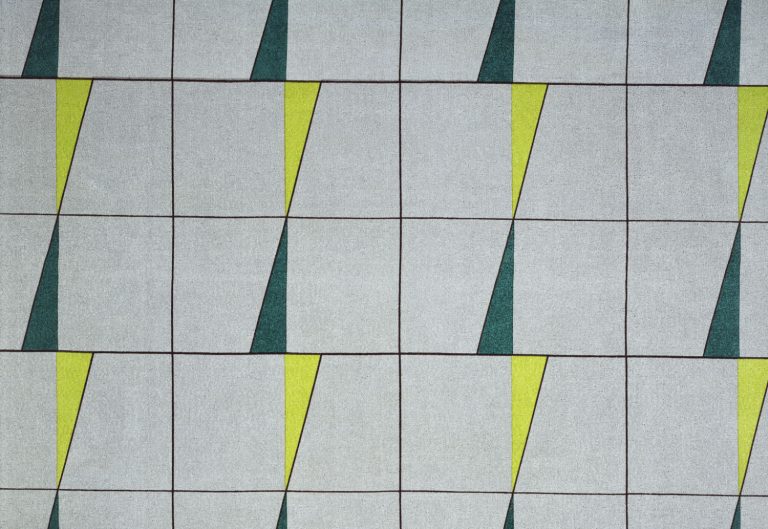

Some stores, such as the drapery and bedding manufacturer J. London & Company, extended their sales nationally. David Stapler of Stapler’s Fabrics—which started as a pushcart in 1892—became an ambassador for exclusive fabrics and textiles inspired by Philadelphia’s history and art. David & Dash made custom textiles for Atlantic City hotels and grew rapidly into a business with designs featured in museums and university collections, including The Design Center at Philadelphia University and the Textile and Costume Collection at Jefferson University. Internationally, Samuel Goldberg, of Sam Goldberg’s Fabrics, traveled from the streets of Philadelphia to Europe, Latin America, and Asia to hand-pick fabric choices for his clients. Goldberg’s personal touch and stylistic eye attracted the business of public figures like Jacqueline Kennedy (1929-94) and couture designers like Christian Dior (1905-57).

Nevertheless, Philadelphia’s fabric businesses declined during the 1960s controversy over the proposed Crosstown Expressway, which would have run through South and Bainbridge streets. Shop owners and customers fled from Fourth Street to the suburbs in anticipation of demolition, and many of the businesses closed in the process.

In 1996, seeking to generate new publicity, businesses on South Fourth Street formed a merchants association called “Shops of Fabric Row,” led by Dan Sullivan (owner of Maggie’s Drawers, opened in 1993). The group’s advertising caught the attention and support of Councilman Frank DiCicco (b. 1946) and led to the city officially designating South Fourth Street as “Fabric Row.” By 2015, a steady decline of foot traffic prompted the South Street Headhouse District to begin major Fourth Street renovations and fund-raising to attract new retailers ranging from traditional fabric and upholstery stores to ready-to-wear apparel, restaurants, and performing arts venues.

In the early decades of the twenty-first century, fabric stores that had been open for generations, including Marmelstein’s and Albert Zoll’s fabric store, closed their doors. The Philadelphia History Museum in 2016 featured an exhibition called “Philadelphia’s Fabric Row: the Pushcart Years, 1905-1955.” However, the exhibit also noted the presence of a new generation of entrepreneurs. As of 2018, eleven fabric stores remained open on Fabric Row, including Fleishman Fabrics and Supplies, Maxie’s Daughter, and Valentia Fabrics. Fabric Row is not simply a street—it is a culturally dense and rich center marrying history with prospects for a unique and innovative future.

Danielle D’Amelio is an M.A. student in the Department of English at Rutgers University-Camden. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History