Fairmount Park Houses

Essay

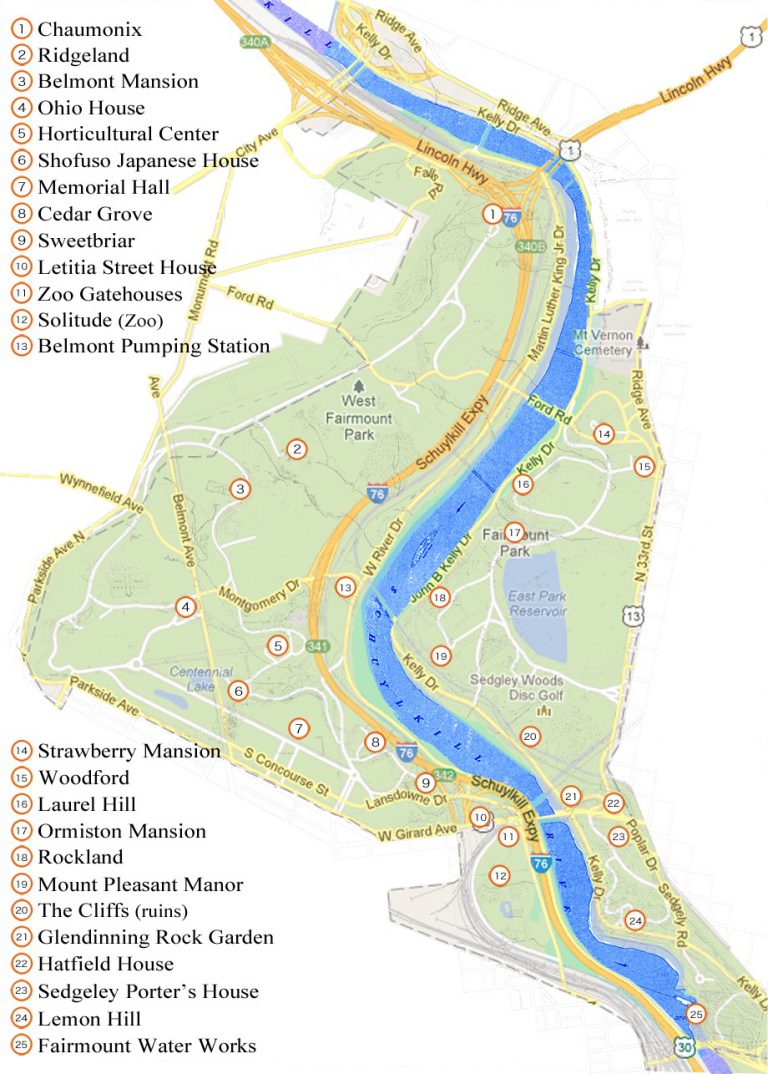

From the mid-eighteenth century, prominent Philadelphians looking for a rural, healthy, scenic environment built small mansions, or villas, along the Schuylkill River, one of two major waterways that define Philadelphia’s geography. In the early nineteenth century, the city began to acquire properties along the Schuylkill, including these villa houses. These purchases culminated in the 1855 creation of Fairmount Park, which stretches for five miles along both banks of the Schuylkill.

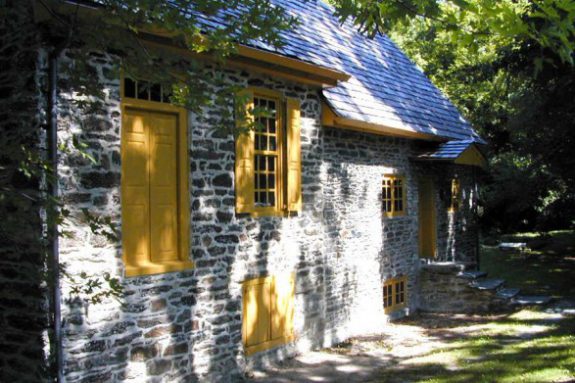

Most of the architecturally noteworthy houses, the “Fairmount Park houses,” existed within Fairmount Park on the east and west sides of the Schuylkill. Dating to the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, they make up a remarkable collection of historic landmarks in one of America’s largest urban parks. Over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Fairmount Park houses transitioned from private to public ownership, were adaptively reused, and often became historic house museums. These houses have served as a bellwether for how Philadelphians have conserved and used their historic architecture.

A rural environment close to their business concerns in the city attracted commercial elites who were key figures in the busy port city of eighteenth-century Philadelphia. Although there had long been dwellings of many types along the Schuylkill, by the 1740s, as the city grew more prosperous, patrons began to build a number of larger houses along the river. The construction of elegant houses along the Schuylkill, reminiscent of developments such as Richmond and Twickenham along the River Thames near London, occurred in Philadelphia especially in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

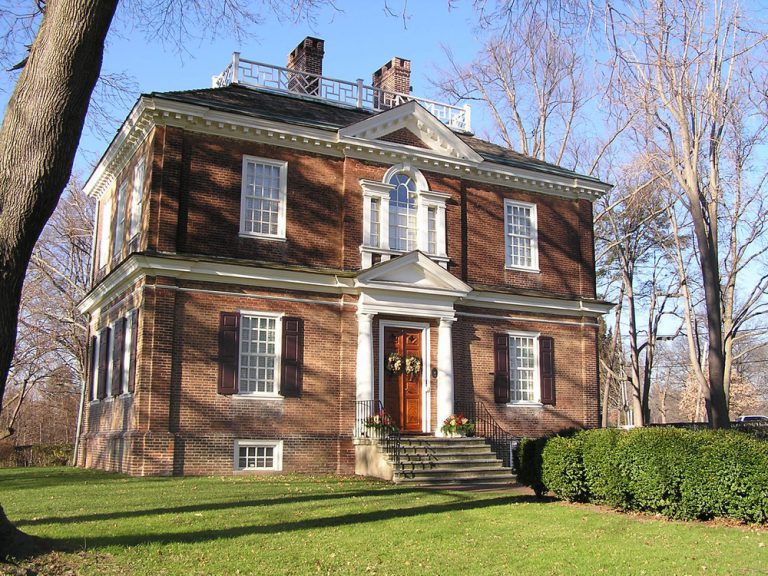

Pre-Revolutionary observer Patrick M’Robert noted how the country around Philadelphia was “interspersed with genteel country seats.” Houses were not evenly distributed, and concentrated more densely on the east side than on the west. On the east side of the river, one of the first noteworthy houses was The Cliffs (prob. 1750s), built for merchant Joshua Fisher (1707–83). A complicated series of land transactions in the 1750s led to construction of several houses, including Woodford (1756, enlarged 1772) by Philadelphia merchant William Coleman (1704–69) and Laurel Hill (1767) for wealthy widow Rebecca Rawle (1730–1819). Architectural historians have generally agreed with John Adams (1735–1826), who called Mount Pleasant (1762–65) “the most elegant seat in Pennsylvania”; it inspired other Georgian mansions built in the 1760s or later, such as Cliveden, Port Royal, Laurel Hill, or expanded, as at Woodford. On the west side of the river, the largest house built during the colonial period in the area that later became Fairmount Park was Lansdowne (1773, burned 1854), for John Penn (1729–95), the last colonial governor of Pennsylvania.

Building continued and even accelerated after the Revolution. By the 1790s, Philadelphians used the term “villa,” suggestive of a semirural retreat close to a city, to describe these houses. John Penn’s cousin John Penn Jr. (1760–1834) built a small villa inspired by a German hunting lodge in about 1785, called The Solitude, which later became part of the Philadelphia Zoo. Built in about 1789, Strawberry Mansion (originally Summerville) served as home to several prominent Philadelphia lawyers, jurists, and political leaders, including William Lewis (1752–1819) and Joseph Hemphill (1770–1842). Hemphill added the large Greek Revival wings to the original center section, creating the largest of the Fairmount Park houses. In 1797, merchant and politician Samuel Breck (1771–1862) constructed Sweetbriar, although it functioned for him as a permanent residence rather than a retreat from urban life. The final villa in what became Fairmount Park, Rockland, was completed between 1810 and 1815, bringing to a close about eighty years of building along the Schuylkill’s banks.

Owners built villas for various reasons. Health—especially to avoid frequent yellow fever and cholera epidemics—motivated some, while others sought to display wealth, taste, and status. Scant information exists about the designers of these houses, although most scholars agree that capable master builders who were likely members of the Carpenters’ Company drew on pattern books widely available in the American colonies especially after the 1750s. The houses reflected a cornucopia of architectural taste, including examples of Georgian, Palladian, and Federal styles, a veritable catalogue of colonial architecture when taken as a whole.

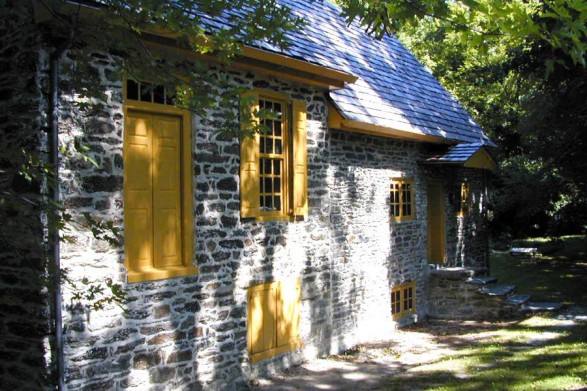

Over the course of the nineteenth century, industrialization and suburban expansion made river villas less attractive. Slowly from the 1820s, in an effort to preserve its drinking water supply, Philadelphia began purchasing the land that became Fairmount Park. Lemon Hill (1799–1801), an elegant neoclassical house built for merchant-trader Henry Pratt (1761–1838), was part of the first parcel acquired by the city. By the end of the 1860s, many of the original villas were under Fairmount Park ownership. Within Fairmount Park, less elaborate houses connected with the region’s early manufacturing also existed. Historic RittenhouseTown, established as a paper mill in the 1690s, included a number of vernacular structures, many destroyed by Fairmount Park authorities in the 1890s, and represented both industrial and domestic history in the park.

Although some property owners made efforts to retain control over villas—and this may have resulted in more effective public/private arrangements over time—for the most part houses along the Schuylkill became public property, sometimes to their detriment. Over the years, the city adapted many of the Fairmount Park houses to other uses, including restaurants, beer gardens, employee housing, and rental properties. Such active use served to protect the houses, as buildings generally underwent only minor, and mostly reversible, changes. At the same time, it demolished many outbuildings in the park that required extensive maintenance and upkeep.

The houses of Fairmount Park were situated in ornamental as well as practical landscapes. A drawing by Pierre du Simitiere (1736–84) shows the garden of William Peters (1702–86) at Belmont (built 1745), replete with cherry trees, gravel walk statuary, and a Chinese temple. Such landscapes were largely lost by the late nineteenth century, although the city made some effort in the early twenty-first century to restore view sheds and the relationship to the river, as at Lemon Hill. Also lost were many outbuildings that would have supported these villas and were a critical part of their aesthetic and functional landscapes.

The Centennial Exhibition of 1876, which drew nearly ten million visitors to Philadelphia to celebrate the history and achievements of America, increased interest in colonial history and architecture and an awareness of the special character of Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park houses, although it took time for these ideas to result in action. The Letitia Street House, initially believed to be the oldest house in Philadelphia and William Penn’s city residence—it was neither—was moved from Center City Philadelphia to Fairmount Park in 1883, the year following the bicentennial of Penn’s arrival. Lemon Hill, which in the late nineteenth century had functioned as a restaurant and ice cream parlor, became a striking example of restoration and reuse. While the Philadelphia Museum of Art was erected on Fairmount in the 1920s, the museum director, architectural historian Fiske Kimball (1888–1955), restored the house in 1926 and lived there until the 1950s. Indeed, Kimball was a pivotal figure in championing the historical and aesthetic importance of the Fairmount Park houses, which he referred to as the “Colonial Chain.”

Efforts like Kimball’s set the stage for renewed interest in the preservation of buildings, moving them toward museum status. As a result, during the twentieth century, citizens became increasingly concerned to see these material fragments of early America preserved and made available to the public. Although Philadelphians and tourists often thought of the villas along the Schuylkill River as the “Fairmount Park houses,” the term also included other structures, including some that had been relocated to the park. An early example, Cedar Grove (1748) was originally located in the Frankford section of the city along the Delaware River, but moved to Fairmount Park in 1926–28.

The Bicentennial resulted in enhanced efforts to repair and preserve the buildings in anticipation of millions of visitors. Controversy erupted in the late 1970s and 1980s about caretakers being allowed to live for free in some Fairmount Park houses. On one hand such arrangements provided security and maintenance, on the other it was seen as a corrupt practice providing free housing. Either way the demise of the caretaker system saw damage to some houses, such as The Cliffs.

Beginning in the mid-twentieth century, a patchwork of organizations preserved and managed the Fairmount Park houses. Although owned by the city, differing management arrangements, many with patriotic women’s service organizations such as the Committee of 1926, the Colonial Dames of America, and the Women for Greater Philadelphia, resulted in a unique character for each house. By the early twenty-first century, arguments by some cultural leaders and government authorities that there were too many historic house museums in the city threatened the futures of the Fairmount Park houses. Some of the houses tried to adapt to these changed circumstances. The earliest villa in Fairmount Park, Belmont Mansion, for example, characterized a shift made in the stories told and the history interpreted by historic houses in Philadelphia. Originally maintained as the home of early Pennsylvania statesman William Peters (1701–86), it became better known in the late twentieth century as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Others remained open as more traditional house museums highlighting architecture and elite owners, while still others functioned as hostels, offices, or rental venues.

Since the mid-eighteenth century the banks of the Schuylkill River have been a scenic focal point for Philadelphians. The small mansions and villas that became a part of Fairmount Park retained a significant presence as cultural symbols of a period signifying Philadelphia’s role as a leading city and, later, as contributors to the environmental centerpiece that is Fairmount Park.

Stephen G. Hague teaches British and modern European history at Rowan University. His research interests center on social, cultural, and architectural history, and he is the author of The Gentleman’s House in the British Atlantic World, 1680–1780. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University