German Reformed Church

Essay

From the beginning of the eighteenth century, the German Reformed Church played a role in developing the religious landscape of southeastern Pennsylvania. Along with other Reformed churches, the German Reformed Church provided a spiritual home for German immigrants and their children that, over time, also served as a medium for adapting to American culture even as many congregations supported their own schools and social services and retained German as a language in worship and basic education through the nineteenth century. Although its strength remained outside of Philadelphia proper, into the early twenty-first century the German Reformed Church in Philadelphia kept up its principal congregation as a touchstone for Reformed practices in worship and social outreach.

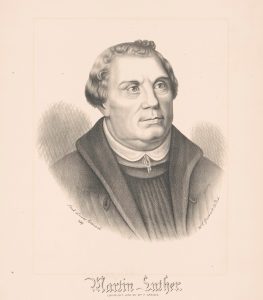

The path to a German Reformed Church in the Philadelphia area began in Europe in 1517, when Augustinian monk Martin Luther (1483-1546) composed his 95 Theses, initiating the “Reformation.” Within six years of Luther’s Theses, Huldrych (or Ulrich) Zwingli (1484-1531) published the charter for the Zurich (Swiss) Reformation. These doctrines developed further as Heinrich Bullinger (1504-1575) and John Calvin (1509-1564) carried them into the western Holy Roman Empire. In that area, at a time of disputes regarding interpretation of the Lord’s Supper, Frederick III of Simmern (1515-76), Elector of the German Palatinate (a region of southwest Germany), sought unity by commissioning the 1563 Heidelberg Catechism. Several Dutch synods also began to follow this style of religious instruction. The Heidelberg Catechism continued as a teaching and preaching tool as well as a guide for the faith of the German Reformed Church (ultimately United Church of Christ) into the twenty-first century.

German and German-Swiss farmers, laborers, artisans, and redemptioners (indentured servants) brought their religious practices to Pennsylvania and the mid-Atlantic region as they migrated to find economic opportunity, peace, and freedom of worship. By the late seventeenth century, German immigrants had settled near Philadelphia in a town they named “Germantown” (incorporated into Philadelphia in the nineteenth century) and began farming in Montgomery and Bucks Counties. With their personal faith, but without pastors, they worshiped in their homes. These German religious folk identified as Lutherans, Amish, Mennonites, Moravians, and Dunkards. By the early eighteenth century, the first official German Reformed congregations were emerging in America. The Reformation had set a path of continued “reform,” thus a “Reformed” German faith, not to be confused with any other German faith. In 1710, Sam Guldin (1664-1745), Pennsylvania’s first Reformed minister, preached in Germantown, but he did not attempt to organize a formal congregation.

1720s: Twelve Congregations

In the 1720s, John Philip Boehm (1683-1749), a schoolmaster, organized twelve Reformed German congregations in Pennsylvania, including the congregations at Falkner Swamp, Skippack, White Marsh, and Philadelphia. In 1727, George Michael Weiss (1697-1762) and four hundred of his congregants arrived in Philadelphia from the Palatinate. Weiss began to minister to the Philadelphia “church” founded by Boehm. In 1730, Weiss returned to Europe to raise funds for the fledgling church, but he returned the following year with empty hands. He moved to New York and ministered there for the next fifteen years. Following Indian attacks, he returned to Pennsylvania and tended to congregations in Montgomery County until his death. Although Weiss did not remain in Philadelphia, his early congregants considered him the first pastor of the German Reformed Church they continued to cultivate.

Before building the German Reformed Church (“Old Reformed”), congregants worshiped in members’ homes and then in a small frame house on Arch Street that they shared with a Lutheran congregation. In 1741, the German Reformed congregation purchased a lot on the southeast corner of Fourth and Sassafras (later Race) Streets. In 1747, they completed their hexagonal church building, one of the earliest German Reformed churches in America. As time passed, the congregation used a portion of the land later known as Franklin Square as a church burial ground.

German settlements continued to spread through Pennsylvania into Berks, Lehigh, Lebanon, and Lancaster Counties. In 1742, Count Nicolaus von Zinzendorf (1700-60), bishop of the Moravian Church, arrived in Pennsylvania. He attempted to unite German faiths—Lutherans, Reformed, Moravians—into one church. These faiths each had unique spiritual confessions, and John Philip Boehm resisted the unification efforts. Still actively serving German Reformed Christians in central and eastern Pennsylvania, Boehm called on the Dutch Reformed Church in New York to send him more Reformed ministers. The Church answered his call with the second pastor of Philadelphia’s “Old Reformed Church”—Michael Schlatter (1716-90).

When Schlatter arrived in America, he found congregations of German settlers scattered throughout New York and Pennsylvania. Within one year, as directed by his superiors, he organized the Reformed ministers and congregations into a coetus (synod). Given the diversity of German religious sects competing for the devotion of German immigrants, Reformed leaders welcomed this new organization. The second coetus, in 1748, adopted the Heidelberg Catechism. Schlatter continued his work in Philadelphia and traveled through the regional colonies on mission trips. The German Reformed congregation in Philadelphia grew in numbers and in prosperity. In 1774, it replaced the hexagonal church with a larger building, one that could seat three thousand people.

Americanization and Assimilation

In the surge of postwar nationalism that followed the American Revolution and the War of 1812, leaders of Reformed congregations faced issues of Americanization and cultural assimilation. Throughout the eighteenth century, German Reformed churches had conducted services in German. As early at the latter eighteenth century, Lutheran leaders in America discussed the need for their ministers to preach in German and English. During the nineteenth century, congregations began adopting English-language practices both in oral and written forms, a process that took much of the nineteenth century to complete. Fewer in number, Danish Reformed churches moved to English most quickly. Given their German roots, German Reformed congregations maintained close connections with Lutherans, with whom they shared a heritage and common concerns about holding on to German as essential to their identity. The pace and extent of language and cultural adaptation varied depending on the concentration of German speakers in the congregations and the commitment of ministers to encourage at least bilingual worship and instruction.

Beginning in the 1820s, as outdoor Christian revivals and charismatic frontier leaders called Americans toward a democratization of Christianity, “Free Synod” congregations emerged. Their desire to hold on to their strong German identity and not give in to English ways began a long and energetic debate, which ultimately led to a schism in the Reformed Church—Free Synod versus Eastern Synod. In 1821, some German Reformed members (Eastern Synod) proposed an “American-style” theological seminary, which they opened in 1825 on the campus of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. Although they perceived their denomination as “a proper American institution,” their seminary continued using the German language lest it “die out in silence.” The seminary moved in 1829 to York, Pennsylvania; in 1837 to Mercersburg, Pennsylvania; and finally to Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1871, where it became Lancaster Theological Seminary.

Through the nineteenth century, Old Reformed in Philadelphia and other Reformed churches provided basic education to local children, including those too poor to pay tuition. Since Pennsylvania had no public education law until 1834, it was common for both German Reformed and Lutheran churches to offer parochial schools. Both denominations provided their members with secular education before and after the development of public schools. Especially in the early years, German constituted the language of instruction.

The “High Church” and the “Low Church”

In the late 1860s, the German Reformed Church consisted of two factions. The “high church” faction wanted to make worship more formal. This group ultimately established Franklin & Marshall College in Lancaster, Pennsylvania. John Henry Augustus Bomberger (1817-90), a German Reformed pastor from Philadelphia, supported the traditional “low church” style of a plain and simple worship. “Under his leadership, the church founded a college in the “village” of Freeland (later established as Collegeville.) The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania granted the college its charter on Feb. 5, 1869, naming the school for Zacharias Ursinus, a sixteenth-century academic and theologian from Heidelberg, Germany.

As Pennsylvania’s population tripled between 1860 and 1920 and its urban population more than doubled, the German Reformed Church maintained a significant presence. A religious survey done by the U.S. Census Bureau in 1926 found the Lutheran Church to be the largest Protestant body in Pennsylvania with 551,000 members. The Reformed Church retained 216,000 members, ranking fifth behind Methodists, Presbyterians, and Baptists. In 1934, the German Reformed Church merged with the Evangelical Synod of North America, and in 1957, this combined group joined the General Council of the Congregational Christian Churches to organize the United Church of Christ.

The main German Reformed Church in Philadelphia, Old Reformed, also experienced transitions. In 1837, because of traffic noise on Race Street and the inadequacies of its second structure, the church expanded with a third building. Following the Civil War, as the area around the church became enveloped by industry and business, many people moved. The congregation followed the migration of its members and built a new church in 1882 at Tenth and Wallace Streets. In 1925, the congregation similarly followed its people to Fiftieth and Locust Streets. In 1967, however, the Old First Reformed Church returned to its original location at Fourth and Race Streets as part of efforts to revitalize Center City Philadelphia. Engaging more directly with the community, the church began presenting a live crèche at Christmas in the 1970s (changed to a refugee nativity in 2018), opened an overnight shelter for the homeless in 1984, and in the early twenty-first century began hosting a jazz workshop. Through mergers in the twentieth century “Old Reformed” formally became Old First Reformed United Church of Christ. As of 2019, it was one of a dozen Reformed churches in the immediate Philadelphia area and scores of Reformed churches in southeastern Pennsylvania.

Brenda Gaydosh is an Associate Professor of History at West Chester University. Her research focuses on varied aspects of the Catholic Church—from a biography about Nazi-era German Provost Bernhard Lichtenberg to current research on the Christian bishops in the DDR. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History