Historical Societies

By Alea Henle

Essay

Over the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Americans started establishing historical societies to collect and preserve historical materials. In 1815, Philadelphia became the fourth U.S. city to host a historical society, the American Philosophical Society’s Historical and Literary Committee. The city’s religious tolerance and central location made it a natural location for religious and ethnic societies. Interests in preserving the history of local places and peoples led to the creation of county, city, and neighborhood historical societies. Leading citizens used history to affirm the area’s contributions to the formation and development of the United States.

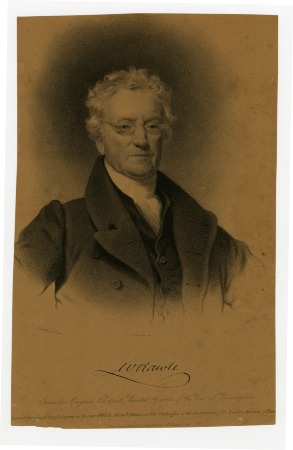

Two early historical initiatives foreshadowed the city’s subsequent history of secular and religious societies. In 1791, pioneering historical editor Ebenezer Hazard (1744–1817) of Philadelphia received a letter from Boston, where citizens had just founded the first historical society in the nation, asking about Philadelphians following suit. Hazard replied such an enterprise would likely be considered the province of the American Philosophical Society. Members of the society came to the same conclusion, albeit a quarter-century later, and established a committee to investigate the history of the United States in general and Pennsylvania in particular. Roughly contemporaneous with this action, Protestant Philadelphians established a Religious Historical Society dedicated to Christian history. The list of founders and early officers included ministers from several denominations: Dutch Reformed Jacob Brodhead (1782–1855), Baptist William Staughton (1770–1829), and Presbyterians Samuel Brown Wylie (1773–1852) and Jacob Janeway (1774–1858). Both societies were moribund by the early 1820s.

Elite members of society formed state societies in the early and mid-nineteenth century to preserve the histories they valued. Amid the celebrations leading up to the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Philadelphians William Rawle (1759–1856), Benjamin H. Coates (1797–1881), and others established the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1824, likely due to the encouragement of collector and chronicler John Fanning Watson (1779–1860). Citizens in New Jersey founded a state society in 1845, while Delawareans waited until 1864. Nineteenth-century historical societies primarily drew their membership from the ranks of professional men of European descent. Women participated, first behind the scenes and later in their own right, but class and ethnic biases persisted. The societies relied on their membership for volunteer action and operating funds as they gathered collections of historical materials, lobbied governments for support and preservative action, and prepared historical publications.

Philadelphia hosted a flowering of religious historical societies founded to preserve denominational histories. In the mid-nineteenth century, Presbyterians and Baptists created societies (Presbyterian Historical Society, 1852, and American Baptist Historical Society, 1853) and located their collections in Philadelphia. Philadelphia’s central location and religious tolerance made it an apt choice, and several denominations followed in the steps of the Presbyterians and Baptists, including the German Reformed (later Evangelical) Church (1863), Society of Friends (1873), and Catholics (1880). The Baptist historical society’s collections were destroyed in a fire at the Publication House in Philadelphia in 1896; members rebuilt the collections, but in the mid-twentieth century the society relocated to Rochester, New York, and united with the Colgate Rochester Divinity School’s extensive historical collection.

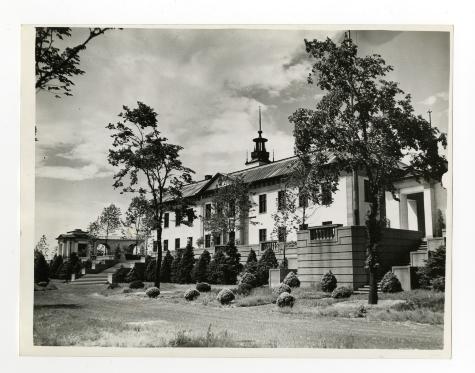

Other new historical societies attempted to redress imbalances and preserve the history of racial and ethnic groups. In 1897, several Black Philadelphians organized the Afro-American Historical Society, also known as the American Negro Historical Society, to preserve and disseminate Black history. Although the Afro-American Historical Society lasted little more than a quarter century, member Leon Gardiner (1892–1945) preserved its collections, later deposited with the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. Academics and historians organized the Swedish Colonial Society in Philadelphia 1909. Less than two decades later, colonial society founder and historian Amandus Johnson (1877–1974) established the American Swedish Historical Museum. The older German Society of Pennsylvania (1764) largely focused on charitable and cultural activities, but established archives in 1867. The Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies, founded in 1971, sought to gather material reflecting ethnic, racial, and immigrant diversity. Over the following decades, ethnic cultural organizations advocated for the history of Latinos and Asian Americans in the area. For example, Philadelphia’s Mexican Cultural Center or Centro Cultural Mexicano sponsored historical lectures.

Most historical societies focused on documenting and preserving place-based local, secular identities—particularly in areas where residents felt overlooked by existing societies. In 1834, responding to the older Historical Society of Pennsylvania’s tendency to focus on Philadelphia, Pittsburghers formed the Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania. Although it proved unstable (reorganized in 1843, failed, then reestablished in 1858), it set a pattern for waves of historical society creation over the following centuries. By the end of the nineteenth century, Bucks (1880), Montgomery (1881), Chester (1893), and Delaware (1895) Counties in Pennsylvania and Salem (1884) and Camden (1899) Counties in New Jersey had established societies. Gloucester (1903), Cumberland (1905), and Burlington (1915) Counties, as well as New Castle County (1934) in Delaware followed suit.

Inspired by the historic preservation movement, residents of various cities, towns, and townships in the region also began to organize societies over the course of the twentieth century. In some cases, existing societies took on preservation responsibilities. The National Society of the Colonial Dames of America assumed care for the Logan family’s house, Stenton. In other instances, residents created new societies to preserve a particular building or site. For example, the Highlands Historical Society (1975) in Fort Washington, Pennsylvania, formed to save Anthony Morris’s Highlands Mansion. The societies’ goals generally expanded to include other preservation activities. The Sharon Hill Historical Society (1991) organized to preserve a train station, but went on to publish a book of photographs. This place-emphasis facilitated the proliferation of historical societies within the region. Philadelphians founded societies to preserve the histories of particular neighborhoods including Germantown, Bridesburg, Frankford, Northeast Philadelphia, and University City. Philadelphia was not alone in hosting multiple societies; Quakertown became home to the Quakertown Historical Society, Quakertown Train Station Historical Society, and Richland Historical Society.

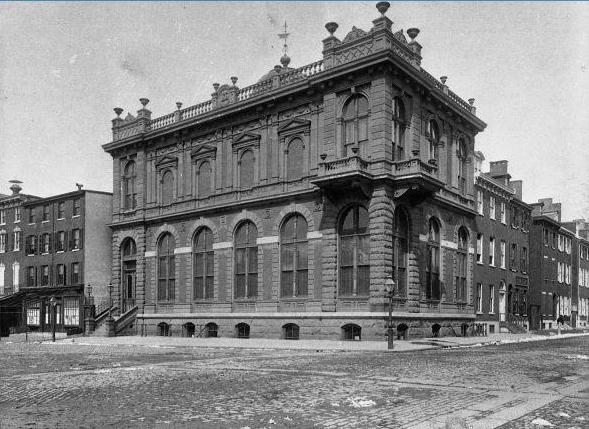

In addition, other societies incorporated historical objectives into their missions over the course of the centuries. Although the American Philosophical Society’s historical committee failed, the parent society shifted to preserve its historical collections and support research. Other institutions, such as the Athenaeum and College of Physicians of Philadelphia, also recognized and acted to preserve their collections’ historical value.

By the early twenty-first century, the region witnessed the creation of even more societies, but encouragement from granting agencies, such as the Barra Foundation, led to consolidation and cooperation among existing societies. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania took on the manuscript collections of the Balch Institute for Ethnic Studies (2002) and the Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania (2006). The Germantown Historical Society merged in 2012 with Historic Germantown, an association of historic houses and museums, to form Historic Germantown: Freedom’s Backyard. Historical societies, individually and in collaboration, supported researchers, developed public programs, advocated for preservation, and more.

Over the course of two centuries, Philadelphians established scores of societies to preserve the history of local places and people. In the process, they laid the groundwork for the region’s extensive historical collections and buildings.

Alea Henle is head of public services librarian at Western New Mexico University. Her research interests explore how efforts to preserve materials for history have shaped what survived. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- C.H. Historical Society seeks national accreditation (WHYY, November 8, 2010)

- Remembering the Atomic Age in Doylestown museum (WHYY, April 9, 2012)

- Maxwell Mansion savors Historical Society of Pa. award (WHYY, July 15, 2013)

- Philly Love Note: 21 million items at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (WHYY, December 3, 2013)

- Delaware Historical Society announces multimillion dollar campaign (WHYY, August 7, 2014)

Links

- Building on History: 100 Years at 13th and Locust (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Germantown Historical Society (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Germantown Historical Society: Librarian Provides Historical Documents for Community (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: The Chestnut Hill Historical Society — An Archival Record of Chestnut Hill (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- PhilaPlace: Stenton House: A Historic House and Community (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Directory of Pennsylvania Genealogical & Historical Societies (PennsylvaniaResearch.com)

- League of Historical Societies of New Jersey