Home Remedies

Essay

Although Philadelphia has been a premier city for medical innovation since the mid-eighteenth century, the diverse peoples of the region also have used home remedies to heal themselves. Home remedies preserve traditional domestic healthcare practices, and they have persisted into the twenty-first century as part of alternative medicine and mainstream scientific therapies. Medical recipes often circulate by word of mouth, making this vernacular culture difficult to recover. Remedies in manuscript, print, and online sources provide clues to centuries of self-healing activities.

In the early colonial period, the scarcity of formally trained physicians, even in Philadelphia, made domestic medical skills particularly valuable. Healing was among Euro-American women’s household duties, and families passed down home remedies between generations. Colonists used their skills in herb gardening, cooking, and distilling to create medicines. A manuscript recipe book compiled by Philadelphia Quaker Catherine Haines (1761–1809) attests to the diversity of ailments treated at home. Haines used common culinary herbs such as thyme, cloves, and mint in her remedies, as well as chemical ingredients such as mercury and alcohol. Those practicing self-care and formally educated physicians shared similar medical worldviews.

Although early Swedish and English settlers imported Old World remedies to the region, they also sought American Indians’ expert knowledge in curing wounds, snakebites, and fractures. Scandinavian settlers and travelers, such as Andreas Hesselius (1677–1733) and Pehr Kalm (1716–79), remarked on the efficacy of American Indian cures. Philadelphian John Bartram (1699–1777), a prominent self-taught botanist and self-healer, compiled and published botanical remedies, including medical recipes from Native Americans. Colonists also valued African American healthcare expertise. In the 1750s, Philadelphia-area newspapers published “Caesar’s Cure” for snakebite and poisoning developed by an enslaved man who gained his freedom by revealing his remedy, which used sassafras and herbs. In the nineteenth century, Philadelphia and West Jersey residents sought home remedies from James Still, a self-taught African American herbalist and doctor from Burlington County, New Jersey.

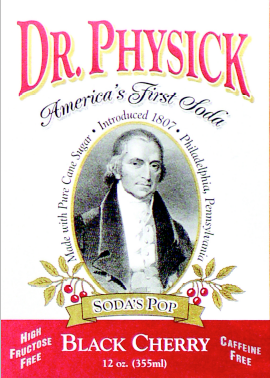

Mid-Atlantic colonists also incorporated a European culture of self-help medical consumerism. A flourishing market in proprietary medicines, such as Daffy’s Elixir and Turlington’s Balsam of Life, allowed colonists to purchase manufactured remedies for home use. Benjamin (1706–90) and Deborah (1708–74) Franklin advertised and sold her mother’s salve for scabies at their print shop into the 1740s. By the early nineteenth century, both German- and English-speaking newspapers were awash with advertisements for store-bought remedies. Some physicians leveraged this lucrative market. In 1807, Dr. Philip Syng Physick (1768–1837) introduced and marketed his artificially carbonated soda water—the precursor of soda pop drinks—for gastrointestinal problems. Despite the popularity of these cures, the pharmaceutical market was unregulated, with no guarantees regarding safety or efficacy.

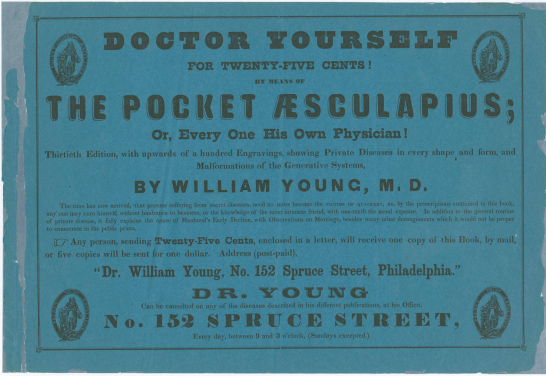

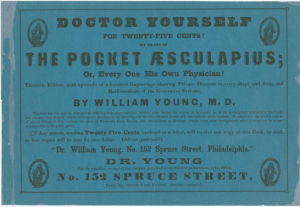

The market for self-help pharmaceuticals bolstered the trade in popular home-health manuals that educated readers in self-diagnosis and treatment. Every Man His Own Doctor: or the Poor Planter’s Physician (2nd ed., 1734) offered “plain and easy means for persons to cure themselves” using inexpensive local herbs. Benjamin Franklin reprinted this manual in seven editions, to benefit the people living in the “unhealthy climate” of the Philadelphia region. The copying of medical recipes in printed manuals into families’ home recipe manuscripts reflected the widespread circulation of self-help health information.

German immigrants to the greater Philadelphia area in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries shared their own home remedies. Between 1762 and 1777, the Germantown apothecary Christopher Sauer (1721–84) authored and published, in German, the first American herbal, The Compendious Herbal. Some Pennsylvania Germans developed a healing culture called “Pow-wow” or “braucherei.” In his 1820 book Pow-wows; or, Long Lost Friend, Johann Georg Hohman described home remedies comprised of herbs, charms, chants, and prayers that channeled God’s healing power. German Americans continued to practice Pow-wow in the twenty-first century, particularly in Berks and Lancaster Counties.

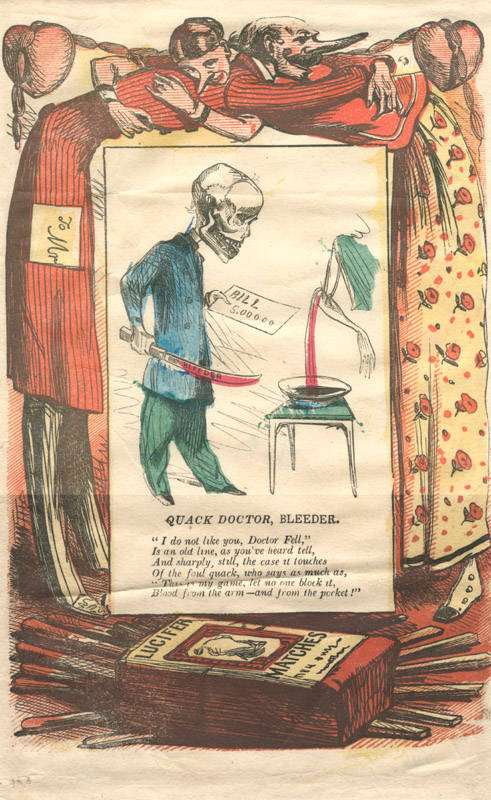

A renewed popular health movement developed in the 1830s as a backlash against the mercury-based purging therapies advocated by Philadelphia physicians such as Benjamin Rush (1746–1814). Journals such as the Philadelphia Botanic Sentinel attest to the local appeal of the Thomsonian botanical movement, which emphasized herbal home remedies that facilitated nature’s curative powers. Home health handbooks remained popular throughout the nineteenth century. Cookbooks, such as Domestic Cookery (1845) by Elizabeth Ellicott Lea (1793–1858), and manuscript recipe books, like that of Philadelphia Quaker Ellen Emlen (1814–1900), continued to incorporate home remedies for a variety of illnesses, including burns, rheumatism, and deafness. At the 1876 Centennial Exhibition, the Philadelphia pharmacist Charles Hires (1851–1937) advertised his health drink, Hires Root Beer, which allegedly soothed the nerves and revitalized the blood. In Philadelphia’s Chinatown, which developed in the late nineteenth century, stores sold home medical manuals and proprietary medicines such as sha hi un for digestive complaints and cholera. Philadelphians of various ethnicities purchased remedies made from Chinese ginseng and other herbs.

In the early twentieth century, the rise of hospitals as the preferred site for healthcare increased patients’ trust in institutionalized physician-centered medicine. However, during the devastating Spanish influenza pandemic of 1918–19, panicked Philadelphians turned to home remedies including castor oil and garlic and patent medicines such as Vicks VapoRub.

In the 1940s, Jerome I. (1898–1971) and Anna (1905–2000) Rodale pioneered an organic farming and naturopathic medicine movement near Allentown, Pennsylvania. Despite the public’s restored confidence in scientific medicine due to the development of antibiotics in the late 1930s, mistrust in formal Western medicine persisted. In 1950, Rodale Press published Prevention Magazine, signaling the beginning of a back-to-nature and natural remedies movement that flourished in the 1960s and 1970s.

Immigration of diverse peoples to the greater Philadelphia area in the late twentieth century expanded the range of healing practices. Patients practicing self-help medicine and mainstream healthcare practitioners began incorporating Chinese herbal medicines and Indian Ayurvedic therapies introduced by Asian immigrants. Stores selling a variety of home remedies—from Mexican manzanilla teas to Caribbean medicinal “bush teas”—reflected the region’s cosmopolitan self-healing cultures.

By the early twenty-first century, websites, blogs, and social media provided new ways of sharing old home remedies. In 2007, a Philadelphia-area blogger posted her mother’s recipe for Deshler’s Salve, a remedy for bruises and wounds. The original recipe was created in the mid-eighteenth century by Germantown resident Mary Deshler (1715–74), but its healing properties were valued a century and a half later. The practice of self-care using homemade remedies and manufactured natural medicines remained as vibrant in the twenty-first century as in the colonial period, with webs of wellness information extending beyond families and local communities to global internet social networks.

Susan Hanket Brandt holds a Ph.D. in history from Temple University and is an adjunct professor of history at the University of Colorado, Colorado Springs. Her 2013 dissertation, “Gifted Women and Skilled Practitioners: Gender and Healing Authority in the Delaware Valley, 1740–1830,” includes information on home remedies. Her article, “ ‘Getting into a Little Business’: Margaret Hill Morris and Women’s Medical Entrepreneurship during the American Revolution,” appeared in the fall 2015 issue of Early American Studies. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Weavers Way's wellness store to hold grand opening Friday (WHYY, July 23, 2012)

- FDA cracks down on illegal diabetes remedies (WHYY, July 23, 2013)

- CHOP enacts new policy to discourage dietary supplement use (NewsWorks, October 14, 2013)

- Harnessing folk remedies to improve modern medication (NewsWorks, October 20, 2015)

Links

- Hires Root Beer: The Great Health Drink (Pennsylvania Center for the Book at Pennsylvania State University)

- Catherine Haines, Notebook (Philadelphia Area Center for History of Science)

- Deschler's Salve Recipe (Blanket in the Grove blog)

- Hires Root Beer History (Dr. Pepper Snapple Group)

- The Recipes Project

- US National Library of Medicine Digital Collections, Medicine in the Americas, 1610–1920, Recipe Books

- The Jayne Building: Chestnut Street's Woulda-Shoulda-Coulda (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Ellen Emlen's Cookbook (Historical Society of Pennsylvania Blog)

- PhilaPlace: Dan Khang Nha Trang, Inc. Chinese Apothecary (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)