Hospitals (Economic Development)

By Guian McKee

Essay

As the twenty-first century began, hospitals and academic medical centers played a central role in the economies of many major U.S. cities, including Philadelphia. As centers not only of patient care but also of scientific research and, often, sources of urban redevelopment, urban medical institutions created jobs in deindustrialized cities and spurred the spatial, social, and economic transformation of neighborhoods. As such, they emerged along with universities as part of a distinct economic sector–the “eds and meds”–often seen as one of the core growth industries of the urban United States.

Few cities exemplified this “eds and meds” model better than Philadelphia. By the first part of the twenty-first century, health care, in particular, constituted a core economic sector in this former manufacturing center. Data from the 2012 U.S. Economic Census showed that hospitals had become the largest employment sector in the city. As of 2013, nine of Philadelphia’s sixteen largest private employers were hospitals (another was a health insurance company); at least six more hospitals ranked among the top fifty employers. Over the previous decade, employment in the city’s health and education sector increased by 18 percent, but declined in all other sectors except one (leisure and hospitality). Although most of Philadelphia’s hospitals were nominal nonprofits, together they generated more than $9 billion in patient revenues. Key institutions included the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania (HUP), Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Albert Einstein Medical Center, Temple University Hospital, Pennsylvania Hospital, and Hahnemann University Hospital. Many other smaller institutions contributed to the sector’s importance as well. It may thus be accurate to understand Philadelphia not only as a deindustrialized city, but also as a medicalized city. Although perhaps an extreme example of this phenomenon, Philadelphia was broadly typical of patterns found around the United States in formerly industrial cities.

In one respect, this development built on the city’s singular history as the location of the first hospital in British North America (Pennsylvania Hospital) and the first medical school (at the University of Pennsylvania). Yet in other ways, the centrality of Philadelphia’s hospital sector was the product of specific choices made in recent decades. The emergence of this urban health care sector, however, was not an unqualified benefit, in Philadelphia or elsewhere. This tension can be understood by tracing the sector’s development across three areas: land use and financing, labor, and taxation.

Land Use and Financing

Philadelphia leaders first came to view the hospital sector in economic terms during the 1970s. In 1974, the city established a municipal Hospital Authority (as authorized by Pennsylvania’s Municipal Authorities Act of 1946) with the power to issue tax-exempt revenue bonds that could be used to finance hospital expansion projects. Although the Hospital Authority issued $1.25 billion in bonds between 1974 and 1985, it also became known as a nest of political infighting and patronage. According to a 1987 study of the authority by the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC), the city’s hospital administrators viewed the Hospital Authority as “autocratic, unreasonable and uncooperative.” During the 1980s, Mayors William Green (b. 1938) and Wilson Goode (b. 1938) further prioritized the health care sector as a potential source of jobs and economic development. Under Green, the authority also expanded its activities to include colleges and universities, and as a result became known as the Hospitals and Higher Education Authority of Philadelphia. Shortly after taking office in 1984, Goode proposed reorienting the functions of the authority to encompass not just project financing but also coordination of the local health care sector and, specifically, the pursuit of economic development through hospital expansion.

Redeveloping the site of Philadelphia General Hospital (PGH), the city’s former municipal hospital in West Philadelphia, provided a test case for the city’s ability to implement this model of development. In 1975, faced with PGH’s outmoded physical plant and a pressing municipal budget crisis, Mayor Frank Rizzo (1920-91) made the controversial decision to close the hospital. Ignoring heated protests and widespread opposition, Rizzo replaced the public hospital with a system of free primary health care provided at decentralized clinics around the city, along with subsidized emergency and specialty care for city residents at private hospitals. In January 1978, the Philadelphia Daily News observed that “for all practical purposes, Philadelphia now has socialized medicine.” Although the new system initially received widespread praise, by the 1990s many of the clinics had long waiting lists, and the city increasingly strained to finance the program, particularly hospital care.

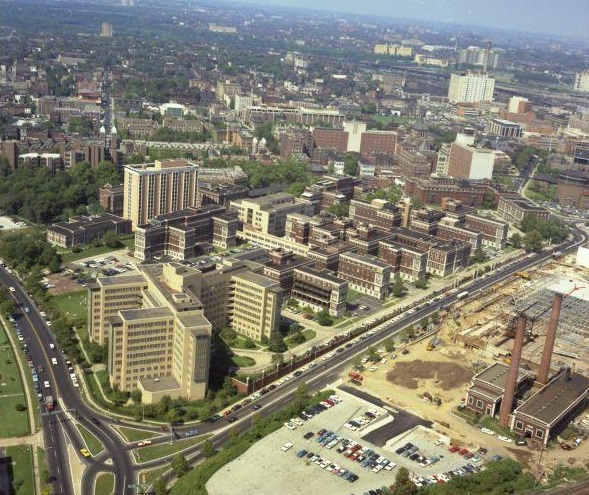

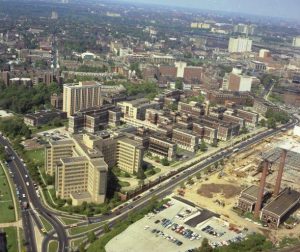

Reusing the PGH site posed other challenges. PGH had occupied twenty-one acres adjoining the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Children’s Seashore House, and the Philadelphia Veterans Administration (VA) hospital, as well as Philadelphia’s Convention Hall and Civic Center. The University of Pennsylvania and Drexel University campuses lay just blocks away, with Center City Philadelphia only a short distance across the Schuylkill River. Highways and mass transit served the area as well. The land, as a result, had significant value. Clearance of the site took three years because of the hospital’s size and solid construction, as well as the need to relocate utilities. Contractors finally completed the job in early 1982, leaving only PGH’s distinctive exterior fence of wrought iron separated by pillars of red brick surrounding much of the site to remind visitors of the earlier structure.

Consortium Makes Progress

As demolition moved toward completion, the Rizzo administration charged the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation (PIDC) with overseeing the redevelopment of the PGH site. After financing for an early private development plan collapsed in the high inflation environment of the early 1980s, PIDC partnered with the PGH Development Corporation (PGHDC), a newly organized consortium formed by HUP, CHOP, and Children’s Seashore House. PIDC and PGHDC developed a plan for multi-institution reuse of the site as the Philadelphia Center for Health Care Sciences. The new consortium received more than $9 million in federal Urban Development Action grants to support new infrastructure construction on the site. This built on a long-standing pattern of federal support for hospital expansion going back to the post-World War II urban renewal and Hill-Burton Act hospital construction programs (both of which had supported earlier stages in the growth of Philadelphia hospitals such as HUP and Thomas Jefferson; the Hill-Burton program had been established by Hospital Survey and Construction Act of 1946). As a nonprofit corporation, PGHDC also secured tax-exempt financing for the project. By the 1980s, such efforts to expand Philadelphia’s large medical centers gained broad political support because they offered the prospect of creating employment at a time when Philadelphia had lost a considerable number of manufacturing jobs.

Initial projects on the site included a HUP clinical research building and CHOP’s administrative and ambulatory care facility. A new Seashore House facility followed shortly. By the time those buildings approached completion in 1989, CHOP and Seashore House had begun planning a $75 million clinical research building and HUP had undertaken a $100 million life sciences research building, both to be built on the PGH site as part of the Center. With the additional HUP and CHOP facilities, which would be completed in 1995 and 1998, respectively, the total cost of the project reached $457 million. During the early twenty-first century, the Center expanded beyond the old boundaries of PGH, as Penn and CHOP purchased and demolished the old Philadelphia Civic Center to the south. CHOP constructed the Colket Translational Research Center on the property, while Penn built the Perelman Center for Advanced Medicine, a 500,000-square-foot outpatient facility. The two institutions subsequently purchased former industrial properties on the opposite (east) bank of the Schuylkill River. Both planned to build on these sites later in the decade. These purchases, with their attendant transition to the institutions’ tax exempt, nonprofit status, removed $112,307 from the city’s annual tax rolls.

By 2016 CHOP employed more than ten thousand people, HUP, nearly six thousand. HUP also formed the Penn Health System, which included such venerable institutions as Pennsylvania Hospital and Presbyterian Hospital. The wider Penn system employed thousands more and had regional alliances extending as far west as Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and east to Princeton, New Jersey. Such alliances connected the system with patients and hence revenue sources across the Philadelphia region. The system’s development was reflective of a wider pattern of mergers and consolidation in the health care industry nationally.

Other large Philadelphia hospitals and medical centers followed HUP and CHOP’s example. Temple University Hospitals and Thomas Jefferson University, both of which initially expanded their medical centers through urban renewal projects in the 1950s and 1960s, forged small regional networks and undertook new construction projects. The Temple University Health System, for example, included the Fox Chase Cancer Center, Episcopal and Jeanes Hospital, and suburban locations in Fort Washington, Elkins Park, and the Oaks Corporate Center. Its medical school established branch campuses in Pittsburgh and Bethlehem. In North Philadelphia, Temple also demolished its original medical school building as well as the Masonic Home of Philadelphia, both located at Broad and Ontario Streets adjoining its main hospital facilities. Further medical center expansions were likely to follow.

Tactics of Smaller Medical Centers

Smaller medical centers in the region also developed integrated health care systems. In New Jersey, the Cooper University Health Care System was based at the Camden Health Sciences Campus on Martin Luther King Boulevard and Broadway in central Camden. Formed in 1986, the system completed a $220 million expansion in 2008, and construction of a new $139 million medical school followed in 2012. Together, the growth of the Cooper campus represented a key part of Camden’s broader redevelopment effort. By 2016, the Cooper system included Cooper University Hospital, Children’s Regional Hospital, Cooper Medical School of Rowan University, and a Cooper-affiliate of the Houston-based MD Anderson Cancer Center. It employed over 6,500 people. In addition, following a failed attempt to incorporate the Rutgers-Camden campus into Rowan University, the state formed a new joint Rowan-Rutgers Board of Governors to oversee health care partnerships between Cooper, Rowan, and Rutgers-Camden.

In the Pennsylvania suburbs, the Crozer-Keystone Health System resulted from the 1990 merger of Upland’s Crozer-Chester Medical Center with Drexel Hill’s Delaware County Memorial Hospital. The system later added Ridley Park’s Taylor Hospital, Chester’s Sacred Heart Hospital (which it renamed as Community Hospital of Chester), and Springfield Hospital. Crozer-Keystone also developed a comprehensive physician network and branched out into health related activities such as the Healthplex Sports Club in Springfield. All these components served to drive patients into the system’s hospitals. In July 2016, a Los Angeles-based for-profit hospital chain (Prospect Medical Holdings) acquired the Keystone-Crozer system.

These mergers and health system expansions reflected the competitiveness of Philadelphia’s health care environment. Featuring five academic medical centers and dozens of community hospitals, the region also had a concentrated insurance marketplace, with only two major private insurance carriers. This limited the leverage available to even the largest hospitals in negotiating insurance payments. Beginning in the 1980s, these factors led to the closure of a number of the area’s weaker hospitals, including Metropolitan Hospital (later known as both Franklin Square Hospital and Cooper Hospital-Center City), St. Joseph’s Hospital, Graduate Hospital, and the Medical College of Pennsylvania Hospital. Others survived bankruptcy procedures or merged into the larger health care systems. A number of these closures resulted from the area’s most disastrous experience with health care system failure. During the 1990s, the Pittsburgh-based Allegheny Health and Research Foundation (AHERF) acquired eight Philadelphia hospitals and medical centers, including most prominently Hahnemann University Hospital and the Medical College of Pennsylvania. Vastly over-leveraged, with inadequate cash flow, and hit hard by changes in Pennsylvania’s Medicaid program, Allegheny collapsed into bankruptcy in 1998. Tenet Healthcare, a national for-profit chain, acquired the network’s Philadelphia hospitals. It subsequently managed Hahnemann University Hospital in conjunction with Drexel University, which used Hahnemann as the teaching hospital for its College of Medicine. Tenet also continued to control St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children, the city’s eleventh-largest hospital by patient revenue.

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, expansion projects at many Philadelphia hospitals and medical centers proceeded with financing provided by the revamped Philadelphia Hospitals and Higher Education Authority, which underwrote nearly thirty expansion projects in the decade preceding 2016. The hospital city thus emerged from a combination of public and private action.

Taxes

For all of the hospital sector’s importance, relying on health care as a source of economic growth came at a significant cost for the City of Philadelphia. Hospitals, as nominally nonprofit institutions, are exempt from paying property taxes to the city. Critics have argued that nonprofit status meant relatively little when the institutions involved generated billions in revenue and were deeply intertwined with government as well as with financial markets (through their bond issues) and the private health insurance industry. In a few cities, such as Boston, major hospitals have provided a “payment-in-lieu-of-taxes” (or PILOT) to reimburse the city for core municipal services.

Philadelphia’s hospitals, however, have continually used their nonprofit exemption to avoid paying taxes on the property they own. For a five-year period during the 1990s, the University of Pennsylvania and other large nonprofit institutions made a voluntary but substantial payment to the city in lieu of taxes. After a 1997 change in state law broadened the tax exemption in a way that called the PILOT program into question, Penn and other institutions ceased these payments–despite the deepening fiscal crisis of the city, especially, its school system. The institutions continued to claim that they contributed to the city through economic development, employment (and its associated taxes), and the provision of health care (including some charity care).

Labor

Health care jobs in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries varied greatly in pay and benefits. Many jobs paid well but required relatively high levels of education. Lower-skilled service workers often found employment in the sector, but at very low wages. A study of health care employment in 2013 found that more than 25 percent of hospital workers in Philadelphia had a high school education or less (38.7 percent had a bachelor’s degree or higher). The workforce was heavily female (70 percent of hospital workers). Nearly 26 percent of hospital workers in the city were African American, and 4.9 percent were Latino.

Hospital unions attempted to address the wages and working conditions in the city’s health care economy as far back as the late 1960s, but hospital unionization persisted as a contentious issue in Philadelphia. Not all of the city’s major hospitals were unionized, including most notably the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. Under the leadership of Local 1199c of the National Union of Hospital and Health Care Workers, CHOP unionized in the early 1970s as did Temple University Hospital, Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, and Hahnemann University Hospital. During a 1972 organizing campaign at Philadelphia Metropolitan Hospital (now defunct), a hospital guard shot and killed Local 1199c organizer Norman Rayford (1938-72). After a protest march to Metropolitan, hospital administrators agreed to bargain collectively for the first time. Norman Rayford day, celebrated on August 28 (the date of the first hospital union contracts in Philadelphia), remains a paid holiday for members of Local 1199c. The union experienced a further surge in organizing after Congress in 1974 amended the National Labor Relations Act to cover health care institutions. HUP, in contrast, did not unionize despite a number of attempts by Local 1199c. The union has been led since its 1969 founding by Henry Nicholas (b. 1936), one of the area’s most prominent labor figures.

In 1989, the National Union of Hospital and Health Care Employees split in a racially-charged dispute over control of union locals. Most East Coast locals joined the Service Employees International Union (SEIU), but Henry Nicholas successfully pushed for Local 1199c to align with the American Federation of State County and Municipal Employees Union (AFSCME), as did most West Coast locals. In 2016, workers at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children and Delaware County Memorial Hospital (in Drexel Hill) voted to join Local 1199c; earlier in the year, nurses at the two hospitals organized under the Association of Staff Nurses and Allied Professionals.

The centrality of hospitals and academic medical centers to Philadelphia’s twenty-first century economy simultaneously provided critical jobs and economic activity in a city reeling from the wrenching loss of a manufacturing base that had previously formed the core of the city’s economy. The new hospital city, however, brought real costs as well. These included the sector’s limited contribution to the city’s property tax-base, the low wages that it paid to many workers, and its frequent physical incursion into residential neighborhoods and commercial spaces. In all of these ways, Philadelphia, and its substantial urban health care economy, proved quite typical of the cities around the United States.

Guian McKee is Associate Professor at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center. He is the author of The Problem of Jobs: Liberalism, Race, and Deindustrialization in Philadelphia (Chicago, 2008) and is working on a new book entitled Hospital Cities, Health Care Nation: The Rise of the Medical Economy and the Transformation of Urban America (under contract with the University of Pennsylvania Press). He is the editor of three volumes of the Miller Center’s series The Presidential Recordings of Lyndon B. Johnson (published by W.W. Norton and The University of Virginia Press). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Industry Profiles: Health Care (Philadelphia Works, PDF)

- PhilaPlace: Philadelphia General Hospital (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The Role of Hospitals in Community and Economic Development (Fels Institute of Government)

- Watch Penn pour the foundation for its $1.5 billion hospital pavilion project (Philadelphia Business Journal)