Immigration (1790-1860)

By James Bergquist | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

The revival of immigration to Philadelphia and its surrounding region in the early nineteenth century provided one of the most powerful elements in reshaping the city’s society. After a decline in immigration during the wars of the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era, the growing industrialization of the Philadelphia region began to attract streams of newcomers. The main flow of these migrants still came, as in colonial days, from northern Europe, especially Ireland, Germany and Britain. But four decades of relatively low migration during and after the American Revolution led to an ethnic society considerably different from what had existed in colonial days.

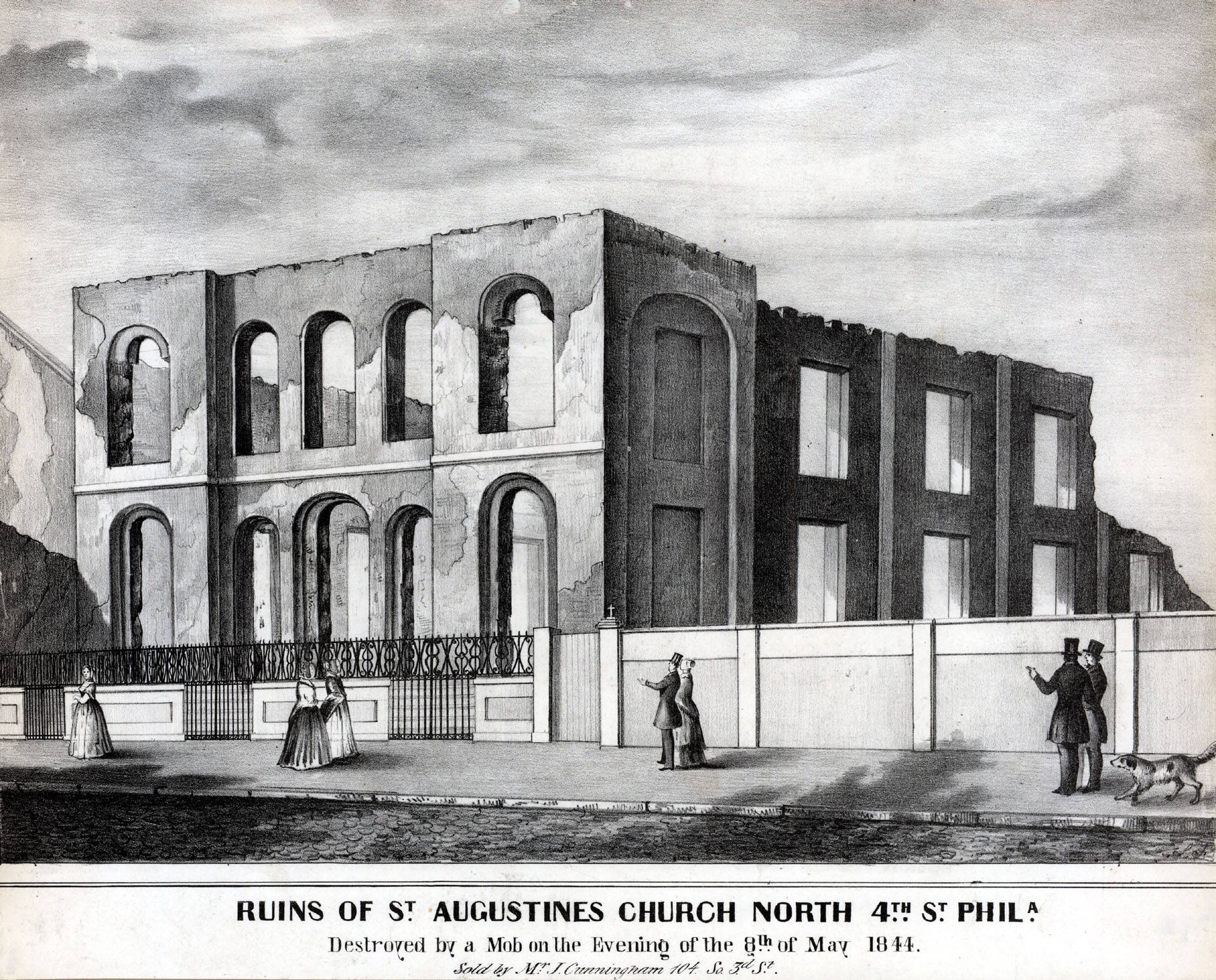

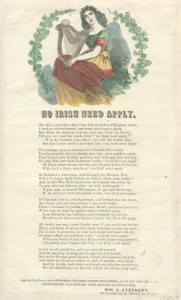

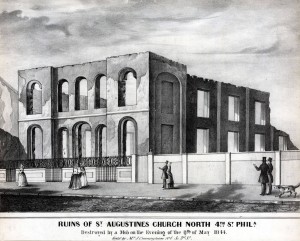

The growing number of Catholic immigrants gave rise to conflict between nativists and immigrants, most reflected in riots in 1844. Immigrants became a persistent issue in the politics of the Philadelphia region and of the nation. The newer immigrants began to find their place in the economic and geographical structure of the city and began to develop their own separate cultures. By the time of the Civil War, immigration had transformed the city.

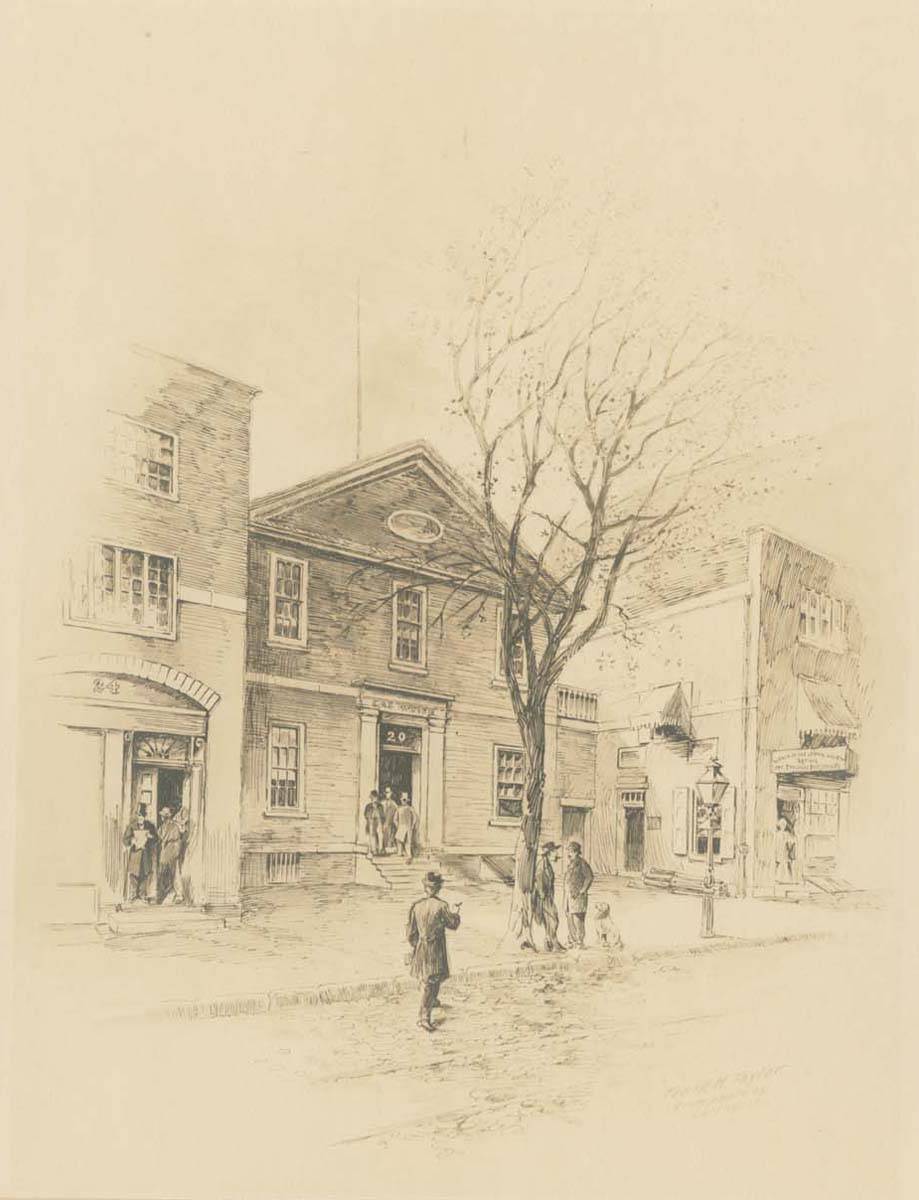

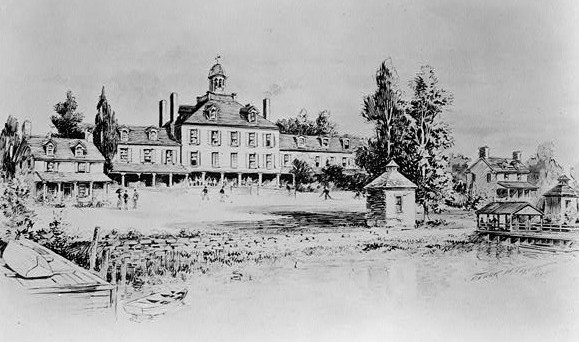

For much of the nineteenth century, access to Philadelphia for immigrants coming directly from overseas was via a quarantine station known as the Lazaretto, located on the Delaware River about eight miles south of the city. The facility was established in 1799 in the wake of the yellow fever epidemic of the previous years, and was maintained by the city’s Board of Health. Ships arriving from overseas ports were stopped for health inspection, and immigrants suspected of having communicable diseases were detained in the hospital at the Lazaretto. This remained the principal station for receiving immigrants until 1893.

Migration Patterns Change

The majority of foreign-born newcomers to Philadelphia, however, came by routes other than through the Delaware Bay. Over the years, the Philadelphia port of entry played a dwindling role in the movement of immigrants into the United States generally and to Philadelphia particularly. In colonial times, the Delaware Valley was a convenient entryway for the many German and Scots-Irish migrants who were heading into the hinterland of Pennsylvania and the back country of Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas. The patterns of migration changed drastically after the American Revolution in ways that favored New York City as the pre-eminent port of entry for immigrants. After the War of 1812, New York City became the foremost port for transatlantic commerce. Its deep-water harbor was a shorter distance from the ports of northern Europe, from which most immigrants came. Trips to Philadelphia required sailing south, around Cape May, then 87 miles north up the Delaware Bay and River to Philadelphia. New York City became the favored gateway into the interior of the U.S. when the Erie Canal, opened in 1825, allowed easy transportation between the Hudson River and the Great Lakes. Immigrants intent upon staying in Philadelphia often arrived in New York and made the overland trip via railroad or canal to Philadelphia.

Thus immigration through Philadelphia’s port declined even as the number of foreign-born in the city increased. During the 1820s, around 12 per cent of the total of new immigrant arrivals nationally entered through the Philadelphia port; by the 1850s, only about 4.5 percent of new immigrants arrived through Philadelphia. By that time New Orleans, with its access to the rapidly expanding Midwest, had become the second largest port of immigration. New York had many ship lines operating frequent service from Liverpool, the point of departure of many transatlantic immigrants. Philadelphia had regular scheduled service from only a few lines. When transatlantic steamship traffic developed by the 1850s, there was little service offered to Philadelphia.

Over the nearly four decades from the beginning of the American Revolution in 1776 until the fall of Napoleon in 1815, the flow of immigrants to the United States fell drastically. The Revolution itself, followed by the European wars that began during the French Revolution, served as discouragement to immigrants traveling from the familiar sources in northern Europe. In the 1790s, the largest source of immigration to the United States was Ireland; an unsuccessful rebellion there in 1798 sent many exiles seeking asylum in America. More notorious perhaps were the smaller number of refugees from France, fleeing the revolution there; they raised suspicion among Federalist Americans because they were thought to be politically dangerous and to support radical Jeffersonian views. In 1798 a Federalist Congress (meeting in Philadelphia, then the nation’s capital) passed a Naturalization Act, one of the Alien and Sedition Acts. This law raised the waiting period for acquiring citizenship to fourteen years; it was reduced to five years in 1802, after Jeffersonians gained control of the government.

Germans, Irish, British

In 1815, at the end of the Napoleonic Wars, immigration began to revive, but remained relatively low throughout the 1820s because of economic recession after the Panic of 1819. The principal arrivals settling in the Philadelphia region were, as before the Revolution, Germans, Irish, and British. Increasingly the Irish immigrants outnumbered the Germans. More importantly, the Irish began to be more clearly distinguished between Protestants and Catholics. The number of Catholic Irish consistently exceeded the number of Protestant Irish in the yearly arrivals beginning in the 1830s. In 1831 a riot broke out in Philadelphia between the two groups. When Protestant Irish began to parade in celebration of the 1691 Battle of the Boyne (in which William of Orange defeated the Catholic James II), Catholics came out in opposition. The affair signified the separation of Irish Catholics from Irish Protestants in the social makeup of Philadelphia. Increasingly after that point, the Irish would be divided into two separate and often conflicting religious groups, with the Catholics increasingly outnumbering the Protestants.

The period from 1830 to 1860 saw a great increase in the flow of immigrants to Philadelphia, as in the nation generally. The forces determining the rise and fall of the flow of immigrants are usually seen in terms of “pushes” and “pulls.” The pushes were the conditions in Europe: increasing pressures of population upon the limited supply of land, poor conditions of the new urban masses, political unrest. The pulls often worked to bring new immigrants to Philadelphia, especially the availability of work in the new industrial environment that was developing there. There were, of course, rises and declines in the rate of immigration, often determined by the state of the economy. In the United States the depressions that occurred after 1837 and 1854 sharply reduced the flow of immigrants. Between those lulls, between 1847 and 1854, there occurred the largest increase in the annual rate of immigrants. The Irish potato famine, the political uprisings on the European continent, and the diminishing conditions of the European worker moved many to come to the United States. At the same time, the American economy was booming, inspired by the gold rush in California and the expansion of the country after the Mexican War.

Philadelphia, with its burgeoning industrial economy, offered great opportunities to those in need of work, especially the unskilled jobs that Irish were able to fill. Textile mills and iron factories were proliferating in the region; mill sites in Delaware County attracted Irish and English newcomers; the building of canals along the Schuylkill and Delaware rivers enlisted the labor of Irish and other immigrants; and immigrants were attracted to the new canal towns such as Conshohocken, Norristown, and Bristol along their banks. In 1832 a new route to the West was opened with the Philadelphia and Columbia Railroad, a part of the state-sponsored Main Line of Public Works, a system of canals and railroads stretching across the state. Much of it was built with Irish labor, and immigrants followed into the new towns being opened up in Chester and Lancaster counties. In New Jersey, similar transportation developments brought new immigrant laborers. In 1834, the first railroad line in the state, the Camden & Amboy Railway, was opened for its entire route between New York harbor and Camden, where access to Philadelphia by ferry was provided. This made Camden and Bordentown centers of transportation development, attracting immigrant railroad and dockworkers. New industries would follow. Since much of the agricultural land in the immediate Philadelphia region was already occupied by 1800, new immigrants intent upon agriculture often made their way toward western Pennsylvania and Ohio, or to the southwest through the Cumberland and Shenandoah valleys into western Virginia and the Carolinas.

Multi-Ethnic Neighborhoods

The population of Philadelphia, which had been around 100,000 in 1815, grew to 400,000 in 1850 and, following the consolidation of the city and county in 1854, to 565,000 in 1860. The great influx of immigrants in the period 1847-54 contributed largely to that growth. In 1860, Irish-born numbered about 16.7 percent of the total population and German-born numbered about 7.5 per cent. As the city grew, immigrant settlement tended to follow the pattern of the “walking city,” where individuals lived within walking distance of their workplace. That brought together people of various ethnicities and classes within one neighborhood. While some neighborhoods might harbor many of the immigrant churches and voluntary societies, one group did not dominate in any neighborhood. German institutions in the colonial period had arisen in the area to the northeast of the center of Philadelphia; in the nineteenth century, the heaviest concentrations of Germans were still seen north of Market Street, but many Germans, more upwardly mobile than the Irish, found residences throughout the city. By 1860, a neighborhood of German Jews formed just to the southeast of the center of the city.

Traditionally the Germans had been of many different backgrounds, given their religious diversity and the variety of provincial origins in a European region not yet united into one nation. The Germans found many reasons to disagree, not only in religion but in cultural matters as well. The complex divisions among Germans made it hard for them to unite politically for any cause (other than opposition to prohibition laws). When immigration from Germany revived after 1815, it became clear that there were considerable differences between those whose arrival dated to the eighteenth century and those who came later. Some of the differences were generational: younger people, who were partly assimilated, many of them of the second and third generations, began to question the exclusive use of German in the churches and other institutions. Controversy over language in the Lutheran churches led to an acrimonious court battle in 1815. The German Society of Pennsylvania, perhaps the most venerable of German institutions, made English its official language in 1818; it did not return to the use of German until the 1860s, after new generations of immigrants had taken over the society. Catholic Germans took pride in the fact that a German-speaking immigrant, John Nepomucene Neumann, was named bishop in 1852. Until he died in 1860, he labored to serve all elements of his multiethnic diocese.

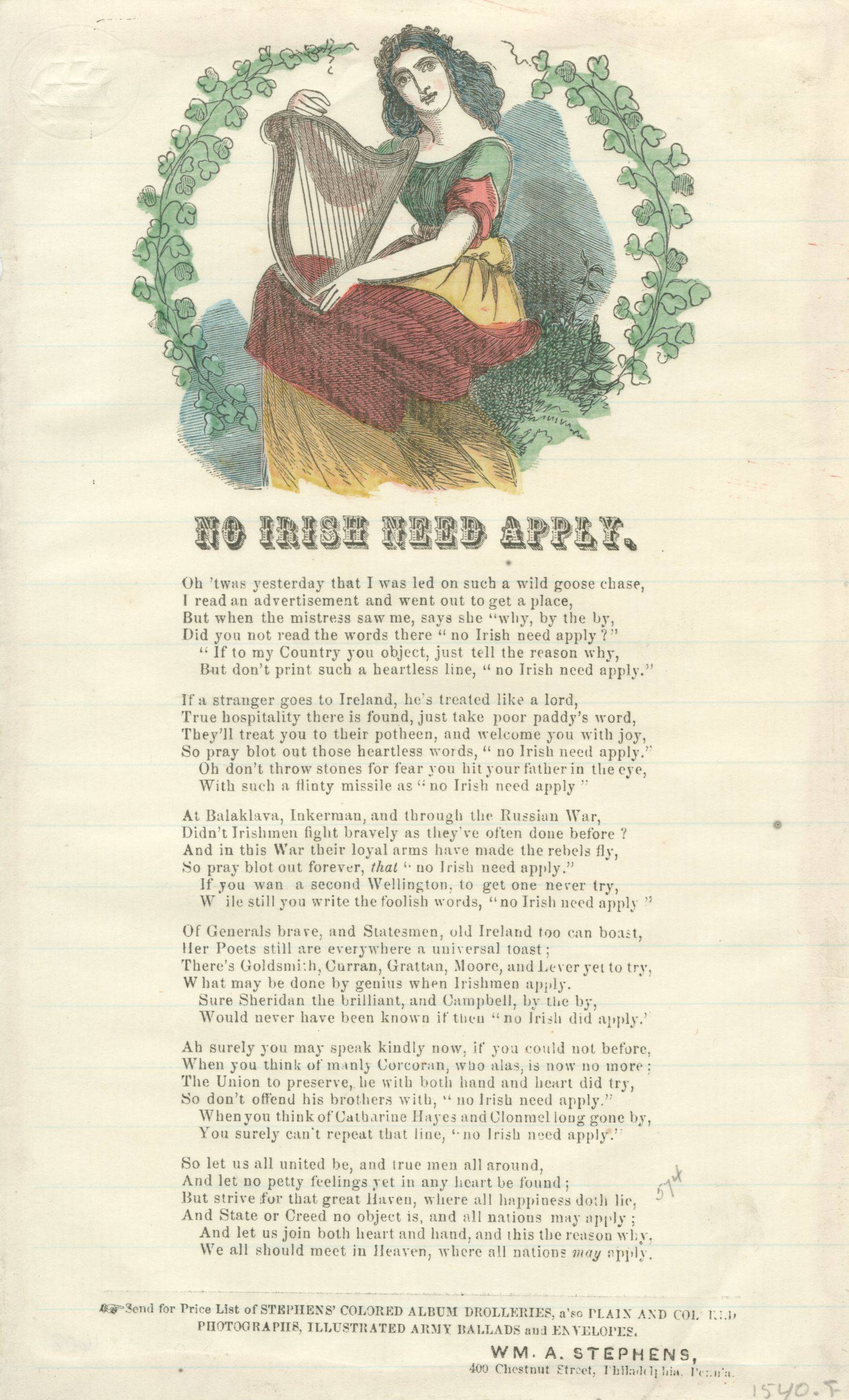

The Irish were even more widely distributed, although heavier concentrations were found in South Philadelphia and in industrial suburbs like Kensington. By the nineteenth century, the group was heavily Catholic, and the church was the center of the Irish institutional life. Irish saloons also developed as seedbeds of social and political life. The Irish were overwhelmingly working-class and subject to the fluctuations of the economy. Nativist riots in 1844, directed particularly at the Irish workers, left a notable mark on the Irish immigrant population, which was sensitive to further attacks. Competition among ethnic groups in the labor market especially affected the mostly-unskilled Irish; the Germans and English more often were found in middle-class occupations, where competition for jobs was less intense. Growing numbers of free Blacks also contended with the Irish in the labor market. Their numbers grew after the passage of Pennsylvania’s gradual emancipation law in 1780. The internal migration of free Blacks across the Mason-Dixon line also increased after Congress closed the international slave trade in 1808; many free Blacks came to southeast Pennsylvania in that northerly migration.

Newcomers from the British Isles were a distant third in the flow of immigrants. Having no language problems, they were less visible because they could easily blend into American life and institutions, and they had no need of founding separate churches. The development of Philadelphia as an Italian-American city was just beginning before the Civil War. The mostly northern Italian group (numbering 417 in the 1860 census) was recognized by Bishop Neumann in 1852 when he established a parish, St. Mary Magdalen de Pazzi, especially for them. The Italians were already concentrated in South Philadelphia.

By 1860, Philadelphia had emerged as the model of the new industrial and ethnic city. Such a development would never have occurred had it not been for the great number of immigrant workers flocking into the region in the early nineteenth century. Inevitably, the presence of these newcomers would foster nativist reaction, which would remain in the society for a long time. Yet no one could possibly call for the exclusion of these elements now embedded in the city’s economy. While the city and its surrounding region were still in control of native white elements, the immigrants had become a force to be dealt with in its economic and political life.

James Bergquist is Professor Emeritus of History, Villanova University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Continue to Immigration (1870-1930)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- Anti-Catholicism in Jacksonian Philadelphia

- For Teachers: German Immigration Unit Plan (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Lazaretto Quarantine Station (USHistory.org)

- U.S. Immigration Legislation Online

- Washington Avenue Steamship Landing and Immigration Station (PhilaPlace.org)

- Duffy's Cut (Immaculata College)