Jews and Judaism

Essay

From the colonial era to the twenty-first century, Jews in the greater Philadelphia area participated in, and contributed to, many aspects of the region’s life. They founded a myriad of synagogues and Jewish organizations, ranging from those with a religious or educational purpose to those encouraging civic engagement and historical awareness. Members of the Philadelphia Jewish community established many pioneering Jewish institutions, some of national scope and others that served as models for similar ventures elsewhere.

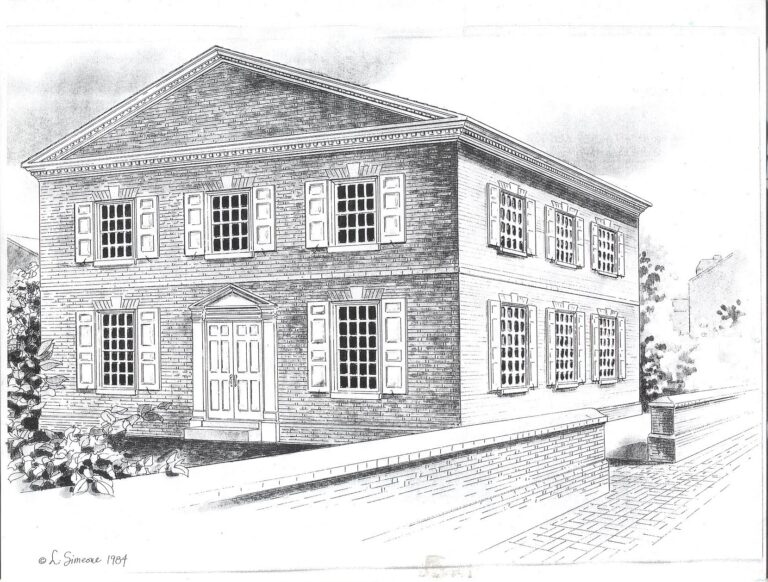

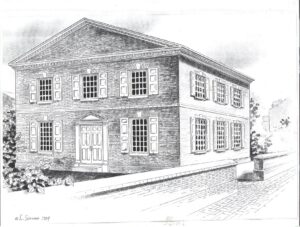

Pennsylvania’s Quaker roots, dating to the 1680s, promised a favorable environment for settlers from minority religious groups that sought economic opportunity and freedom of worship. Although a few Jews had passed through Philadelphia earlier, an organized Jewish community took shape about 1737, with the arrival of Nathan Levy (1704-53) and his brother, Isaac (1706-77), sons of a prominent merchant family from New York. Nathan Levy purchased land on Spruce Street for a Jewish cemetery, and people began gathering for worship in rented quarters during the 1740s. They called their congregation, the first in the city, Mikveh Israel (“Hope of Israel”), a phrase from the Biblical book of Jeremiah. A draft “constitution” dates from about 1770, but a synagogue building (on Cherry and Third Streets) was not dedicated until 1782.

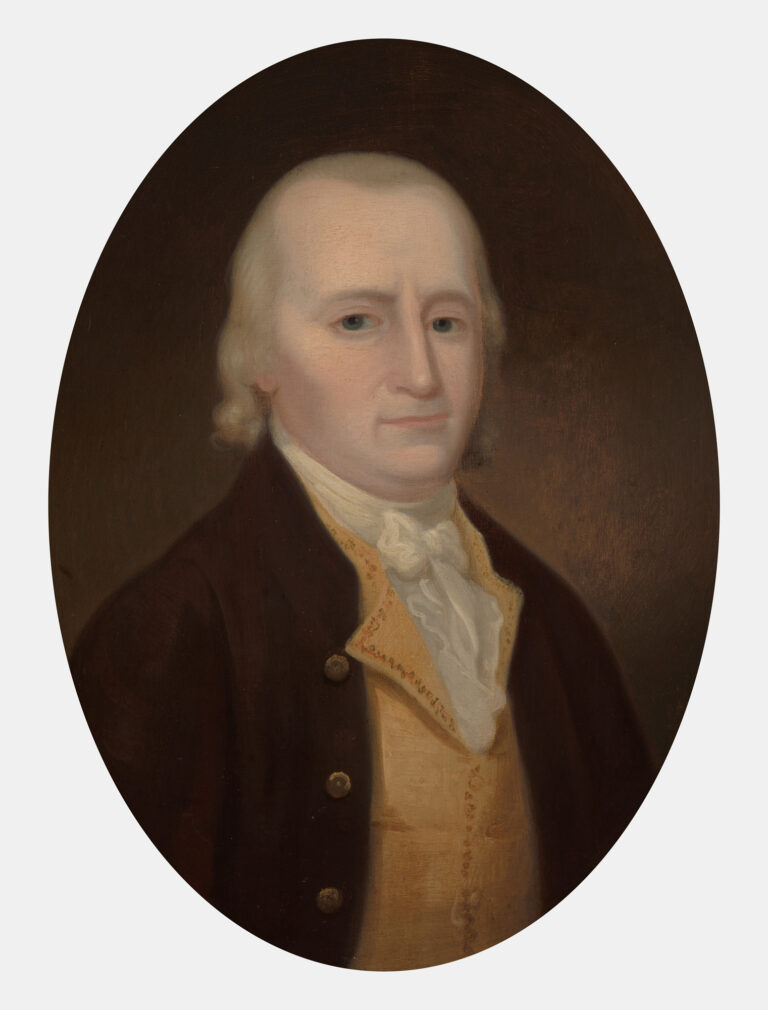

Jews constituted only one-tenth of one percent of the population of British colonial North America, and Philadelphia was one of five towns with significant Jewish communities. By the 1730s and 1740s, some Jews had begun to settle and do business in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, as well. (The best known of these was the prominent merchant Joseph Simon [1712-1804]). An estimated one hundred Jewish persons lived in Philadelphia in 1765, and roughly three hundred by 1775. The early settlers included Jews of both Spanish/Portuguese (Sephardic) and central/east European (Ashkenazic) origin. (Ashkenazic and Sephardic Jews spoke different languages such as Yiddish and Ladino, had different religious customs, and recited the prescribed Jewish prayers to different melodies.) Many of these Jews worked as merchants, shopkeepers, and craftsmen, and some had connections with Jewish merchants in other ports in the colonies, Britain, and the Caribbean, creating a Jewish diasporic community through commerce and even marriage.

During the American Revolution, Jews divided their loyalties between the “patriot” (or Whig) and “loyalist” (or Tory) camps, but most of the 1,000 to 2,500 Jews in the British colonies in 1776 supported the patriot cause; some one hundred Jews served in the Continental Army or local militias. Philadelphia Jewish merchants were among those who signed the Non-Importation Resolutions against Britain, and some Jews provided supplies for the Continental Army or secured critical loans to support the cause. Probably the most famous among these was Haym Saloman (1740-85), a Polish-born exile and escapee from New York, who gained respect and renown as a broker and fundraiser for the Articles of Confederation government. Philadelphia also became a haven for many Jewish refugees fleeing British-occupied New York; Savannah, Georgia; and Charleston, South Carolina.

Pressing for Religious Freedom

In the early years of nation-building, Jews continued to be active in civic affairs. Of particular note, Jonas Phillips (1736-1803), a prominent Jewish merchant who had served in a company of Philadelphia militia during the Revolutionary War, succeeded in getting the new Pennsylvania state constitution of 1790 to remove a stipulation requiring that individuals affirm their belief that both the Old and New Testaments were “given by divine inspiration” in order to take public office—an early example of Jews pressing for religious freedom in the United States. The federal Constitutional Convention meeting in Philadelphia in 1787 similarly had passed Article VI, stating that “No religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.” In gratitude to their new country, Jews jubilantly joined in the Grand Federal Procession in Philadelphia on July 4, 1788, celebrating the ratification of the Constitution. Their religious leader—probably Chazan/Cantor Jacob Raphael Cohen (ca. 1738-1811) of Mikveh Israel—marched alongside Christian ministers, and Jews enjoyed kosher refreshments at a separate table at the end of the parade. This highly symbolic moment exemplified both inclusion of minority religious groups and the protection, or at least toleration, of their religious freedom.

Philadelphia’s Jewish population increased markedly in the early nineteenth century from about 450 in 1820 to four thousand by 1848, due largely to an influx of central European immigrants. As early as 1802, a second congregation—Rodeph Shalom—formed to meet the liturgical needs of the new German-speaking congregants. (The congregation’s first building was probably located on Margaretta Street and Cable Lane.) Thus, Philadelphia became the first American Jewish community to boast more than one synagogue. By 1858, there were seven congregations in the city.

American Jews have always observed religious practices along a spectrum from the most to the least traditional. The Reform movement in America began in the 1820s and gained strength in the mid to late nineteenth century; Orthodoxy and the Conservative movement gradually emerged in reaction to Reform, and the Reconstructionist movement developed over several decades, finally becoming a separate movement in the late 1960s. Though all of the movements were represented in Philadelphia, Robert Tabak, a rabbi who earned his Ph.D. in history at Temple University, observed that “Philadelphia was a center for the Americanized traditionalism that later became the basis of conservative Judaism.”

As Philadelphia’s Jewish population grew in the nineteenth century, prominent Jewish families often took the lead in establishing charitable organizations. The Gratz family proved especially active. Brothers Barnard (1738-1801) and Michael (1740-1811) Gratz, successful merchants and pillars of Mikveh Israel and the Philadelphia Jewish community, used their connections with leading political and literary figures to promote civic improvement and charities. Rebecca Gratz (1781-1869), daughter of Michael Gratz, was an influential philanthropist and educator. Along with her mother, sister, and twenty other Jewish and Christian women, she helped organize the Female Association for the Relief of Women and Children in Reduced Circumstances (1801), a nonsectarian organization that assisted the city’s poor, and she held a leadership position in the association for many years. In 1838, she founded (and served as superintendent of) the first Hebrew Sunday School for Jewish children, many from needy immigrant families (the Sunday School’s first building was on Filbert Street, then called Zane Street, above Seventh). The first Jewish school in the U.S. to have all women teachers, it educated more than four thousand students by the end of the nineteenth century. Gratz and a group of women from Congregation Mikveh Israel established the Female Hebrew Benevolent Society in 1819 (the first non-synagogue-based Jewish charity, which still exists), and Gratz also helped found the nonsectarian Philadelphia Orphan Asylum (1815, Market Street, west of Broad Street) and the Jewish Foster Home (1855, originally on North Eleventh Street and then moved in 1881 to a location near Chew Street and Church Lane in Germantown).

Defining American Judaism

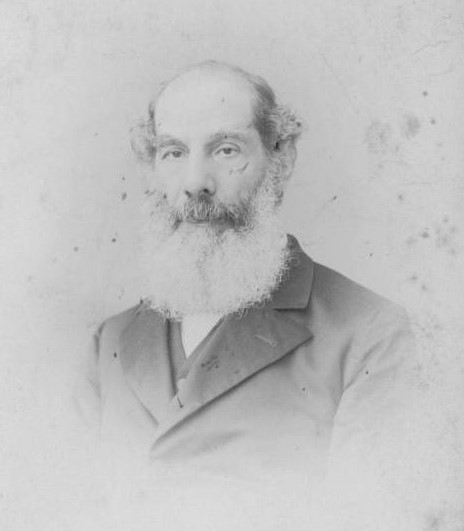

Philadelphia Jews also played important roles in defining American Judaism and building Jewish cultural and educational institutions during the nineteenth century. Among them, Isaac Leeser (1806-68), Chazan (cantor) of Congregation Mikveh Israel from 1829 to 1850, established the first American Jewish Publication Society (1845), Hebrew high school (1849), rabbinical school (Maimonides College, 1867-73), and successful American Jewish newspaper (The Occident and American Jewish Advocate, 1843-69). In addition, he completed the first English translation of the Hebrew Bible by an American Jew (1853). He was also the first Jewish religious leader in the U.S. to deliver regular English sermons and to model an Americanized rabbinate (though he himself was not an ordained rabbi), and produced many textbooks and other educational materials. Leeser opposed the midcentury movement to declare the United States a Christian country, forcefully defending the principles of religious freedom and separation of church and state in his newspaper, The Occident. Commenting on all of the innovations launched by Leeser, Gratz, and others, rabbi and historian Bertram Korn described Philadelphia in the nineteenth century as the “ideal experimental center of American Jewish creativity.” Korn hypothesized that Philadelphia’s smaller size and slower pace (as compared to New York), as well as its rich intellectual and cultural life, may have contributed to this spirit of innovation.

By 1860, some eight thousand Jews lived in Philadelphia, and Philadelphia Jewry was becoming more engaged in the city’s civic and political life. Philadelphia’s rabbis took public positions on the urgent issues of the time. Rabbi David Einhorn (1808-79), who was forced to flee Baltimore in 1861 due to threats from proslavery mobs, continued to champion abolitionism as rabbi of Congregation Keneseth Israel in Philadelphia. Rabbi Sabato Morais (1823-97), of Mikveh Israel, gave a number of stirring sermons supporting the Union cause during the Civil War. Anti-Jewish feeling rose markedly during the war, as critics of inflation and wartime profiteering scapegoated Jews. Yet Jews also gained significant rights during this time. The service of Philadelphian Michael Allen (1830-1907) as an unofficial chaplain in the 65th Regiment of the 5th Pennsylvania Cavalry (although he was forced to resign) led to Congress’s revision of the military code in July 1862 to permit non-Christians to serve as military chaplains. Philadelphia’s Jewish women also played an important role on the home front. The Ladies’ Hebrew Association for the Relief of Sick and Wounded Union Soldiers, organized in May 1863, for example, provided soldiers “irrespective to religious creed . . . with delicacies and clothing while they lie in the army hospitals.” Abraham Lincoln (1809-65) was beloved by many in northern Jewish communities for his actions to defend Jews, for example revoking the 1862 order by General Ulysses S. Grant (1822-85) that expelled Jews from his military department, and supporting the appointment of Jewish military chaplains. After Lincoln’s assassination, black drapes covered the reading tables of synagogues in Philadelphia, as in many other cities, and Jewish religious leaders offered eloquent eulogies. In so doing, they not only shared in the nation’s grief but also reminded everyone that they were part of that nation.

Between 1880 and 1924, two and a half million Jewish immigrants, mostly from eastern Europe, arrived in the U.S., with large concentrations in New York, Chicago, and Philadelphia. These immigrants were generally Ashkenazic, though tens of thousands of Eastern Sephardi and Mizrahi Jews arrived in the U.S. during the same period. Philadelphia’s Jewish population mushroomed from about fifteen thousand in 1880 to around two hundred thousand in 1920. Most of the newcomers settled in South Philadelphia, on Fourth and Fifth Streets south of Pine; others lived in the neighborhood north of Market Street and in Port Richmond. Unlike immigrants in New York, they lived in row houses and boarding houses rather than tenements, but like Jewish immigrants in other cities, many worked in the growing garment industry, while others became peddlers and shopkeepers, among other occupations. Some entered cutting-edge sectors of the economy; notably, optician Siegmund Lubin (1851-1923) became a pioneer in the motion picture industry.

Aiding Newcomers

Philanthropic Jews established a variety of organizations and institutions to assist the newcomers, including the United Hebrew Charities, Jewish Hospital, Hebrew Education Society, Jewish Sheltering Home/Home for the Jewish Aged, and Federation of Jewish Charities. Jewish women launched charitable ventures, including the Jewish Foster Home, the Jewish Maternity Home, the Young Women’s Union (which operated educational programs for immigrants and a settlement house, later known as the Neighborhood Center), and the National Council of Jewish Women. When they were able to do so, immigrants created their own charitable, educational, and cultural institutions, including synagogues, mutual aid and fraternal organizations, free loan societies, hospitals, orphanages, Jewish elementary schools, socialist and Zionist groups, Yiddish newspapers, and a Yiddish theater. The city’s first Russian Jewish congregation was B’nai Abraham, established in South Philadelphia in 1883.

The relationship between more established American Jews and the eastern European Jewish immigrants was complex. Jewish philanthropists provided many critical support services for the newcomers yet were often patronizing toward their foreign-born coreligionists. They sought to Americanize the immigrants as rapidly as possible to reduce growing antisemitism and protect their own standing in American society. For their part, the recent immigrants benefited from the charity of the so-called “uptowners,” while often resenting them. Most of the established Jews belonged to Reform congregations, while most of the newer immigrants, though not all Orthodox (as is often assumed), preserved their ethnic identities and some traditional religious practices, but were not necessarily fully observant. Over time, the differences between the two groups blurred due to Americanization, greater social interaction, and marriages between central European and eastern European Jews.

Other key cultural and educational institutions of the Philadelphia Jewish community emerged at this time as well. The city’s major Anglo-Jewish newspaper, The Jewish Exponent, began publication in 1887. In 1895, Gratz College, the first independent college of Jewish studies in the United States, was founded by a provision in the will of Hyman Gratz (1776-1857), and in 1907, Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning opened. (Dropsie College became the Annenberg Research Institute in 1986 and merged with the University of Pennsylvania in 1993. It was then renamed the Center for Judaic Studies and, in 2008, was endowed as the Herbert D. Katz Center for Advanced Judaic Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.)

As the Jewish population of Philadelphia expanded, more Jews began to settle in neighboring geographic areas. Though a few Jewish traders had come to Delaware in the mid-seventeenth century, more Jews arrived from Philadelphia and Baltimore in the mid-nineteenth century. The Jewish community in Wilmington began to take shape a few decades later, with the formation of the Moses Montefiore Mutual Aid Society (1879) and early synagogues. Delaware’s first congregation was Ohabe Shalom (1880), and a second congregation, Adas Kodesch, built a synagogue on Sixth and French Streets in 1898. The city’s Jewish population grew to about four thousand by 1920, and Jewish leaders established a YMHA, various charitable organizations, and, eventually, a few other congregations—Orthodox, Reform, and Conservative. In South Jersey, the first Jews came to the city of Camden around 1890, and some founded the (Orthodox) Sons of Israel Congregation in 1894 and a YMHA in 1907.

Jewish Farmers

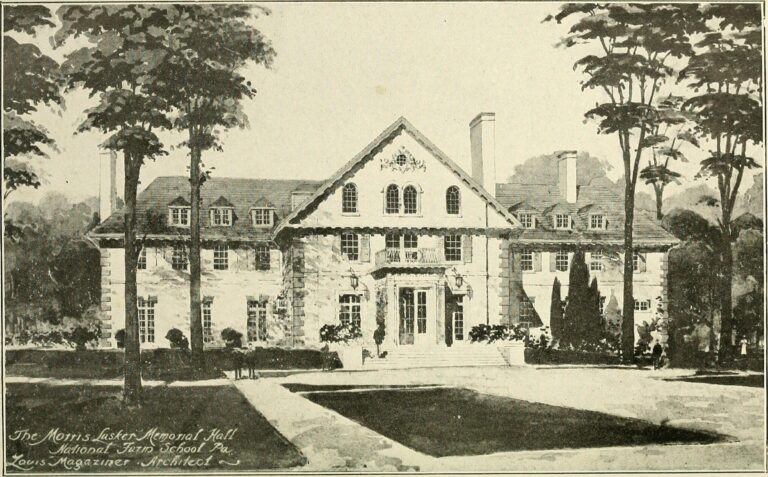

While most Philadelphia-area Jews were city dwellers in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a significant number became farmers. In 1882, a group of Russian Jews, with the help of the Alliance Israélite Universelle (a French Jewish organization), founded Alliance, a farming community in South Jersey. Alliance was followed by Woodbine (established in 1891 by the Baron de Hirsch Fund; it included an agricultural school), as well as Rosenhayn, Vineland, and Carmel (South Jersey), and Toms River, Farmingdale, Lakewood, and Freehold (Central Jersey). There were some Jewish farming families in southern Delaware as well. These communities raised fruits and vegetables and often had manufacturing components; several were especially known for chicken farming. They contributed significantly to the local economy, marketing their products in New York and Philadelphia, and cultivated a rich Jewish religious and communal life for their members. They welcomed European Jewish refugees during the 1930s and, later, Holocaust survivors. Many Jewish leaders at the time urged Jews to take up agricultural pursuits. Rabbi Joseph Krauskopf (1858-1923), of Congregation Keneseth Israel, established the National Farm School in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, in 1896 (subsequently Delaware Valley University), to encourage young Jewish men to study farming. The school was nonsectarian from the beginning, admitting students of all religious backgrounds, and became coed in the late 1960s.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a remarkable group of Jewish leaders emerged in Philadelphia and made enormous contributions to both the city and the religious, cultural and intellectual life of the Jewish community locally and beyond. Often described collectively as “The Philadelphia Group,” they included Rabbi Sabato Morais, Mayer Sulzberger (1843-1923), Solomon Solis-Cohen (1857-1948), Cyrus Adler (1863-1940), and Rabbi Bernard Levinthal (1864-1952). Morais, religious leader of Mikveh Israel, spoke out in support of striking garment workers in 1890. He was also a founder and first president of the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS, the Conservative movement’s rabbinical seminary). Sulzberger, a respected attorney and judge of the Court of Common Pleas, helped to found and was the first president of the American Jewish Committee (created in 1906 to combat anti-Jewish persecution and defend Jewish rights); he was also a major donor and supporter of the world- renowned library at JTS. Solis-Cohen, a physician and a longtime member of the Philadelphia School Board, was also a key supporter of JTS, the Philadelphia Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association, and the Jewish Publication Society. Adler, a Semitics scholar and for a time librarian at the Smithsonian Institution, served on many boards of non-Jewish, Philadelphia-based organizations and also, at one point in his life, headed five major Jewish institutions or organizations simultaneously. Rabbi Bernard Levinthal was widely recognized as the Orthodox unofficial “chief rabbi” of Philadelphia; he also held leadership positions in Agudat Harabbanim (the Orthodox rabbinical organization), Yeshiva University, the American Jewish Committee, the Federation of American Zionists and Mizrachi (the religious Zionist organization). The prominence of such men reflected the rising influence of Jews in Philadelphia’s intellectual, civic, educational, and social life, as well as their place among power brokers in the city.

By the 1920s, the Philadelphia Jewish community was the third largest in the United States. Many of the city’s Jews moved to new neighborhoods, such as Logan, Strawberry Mansion, and West Philadelphia. Significant numbers worked in business (especially retail stores), radio broadcasting, public school teaching, and filmmaking. Quite a few Jewish business leaders and professionals emerged as prominent public figures and philanthropists in the interwar years and beyond. These included attorney and judge Horace Stern (1878-1969), paper box manufacturer Frederic Mann (1903-87), media giant Walter Annenberg (1908-2002), and real estate magnate Albert Greenfield (1887-1967). Among their many accomplishments, Stern served as chief justice of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court; Mann supported the Philadelphia Orchestra and the outdoor music amphitheater in Fairmount Park; Annenberg became editor and publisher of the Philadelphia Inquirer, the Philadelphia Daily News, and other publications; and Greenfield played a leading role in Philadelphia city planning and urban renewal. Journalist and author Dan Rottenberg described Greenfield as “the prototypical immigrant outsider challenging the business elite—Jewish as well as Gentile.” According to Rottenberg, Greenfield was, in many ways, well accepted in broader business and social circles, while retaining his Jewish identity and supporting many Jewish, Catholic, and other philanthropic causes.

Discrimination Between the World Wars

Even as they benefited from socioeconomic and residential mobility, and continued to build their communal institutions, Jews during the interwar period experienced discrimination in admission to large law firms, major banks, insurance companies, colleges and universities, medical and dental schools, social clubs and other organizations, resorts, and certain neighborhoods. Philadelphia Jews responded by creating their own law firms, clubs and associations. By the 1930s, the city’s Jews, like Jews in other American cities, confronted a sharp rise in antisemitism; they were often scapegoated by Americans suffering as a result of the Depression. The broadcasts of Detroit-based “radio priest” Charles Coughlin (1891-1979), replete with antisemitic stereotypes, became popular among segments of the city’s population, and the German-American Bund, a Nazi-style organization in the U.S. that terrorized American Jews, had a strong local presence. (Previously, antisemitism had flared up only occasionally, generally in the context of political rhetoric, such as the struggle between the Federalists and the Democratic Republicans in the late 1790s and early 1800s or invective directed against a Jewish supporter of Andrew Jackson in the 1820s).

By 1940, about 245,000 Jews lived in Philadelphia, and many served in the American armed forces during World War II. Significant numbers on the home front protested Nazi persecution of the Jews and raised funds to assist European Jewry. These difficult years witnessed some other important developments in the Philadelphia Jewish community. Akiba Hebrew Academy was founded in 1946, the country’s first pluralistic Jewish secondary day school, not affiliated with any religious movement; several other Orthodox and Conservative Jewish day schools were established over the next two decades. There were also networks of Folkshulen (Labor Zionist schools, conducted in Hebrew and Yiddish) and Workmen’s Circle Yiddish schools. While many Philadelphia Jews supported the Zionist goal of creating a Jewish state in Palestine, a group of Reform rabbis and laypeople founded the anti-Zionist American Council for Judaism in the Philadelphia area in 1942. Rabbi Louis Wolsey (1877-1953), Senior Rabbi of Congregation Rodeph Shalom in Philadelphia, played a key leadership role, and the council held its initial conference in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in June 1942.

In the post-World War II decades, Philadelphia’s Jewish residents worked in clothing, supermarket, cigar-making and tobacco, electronics, entertainment, liquor, communications, and real estate businesses. Many others found work in public school teaching and public service, among other sectors of the economy. Some employment discrimination persisted into the early 1960s, but lessened markedly by the end of the century.

By the late 1950s, thousands of Jews were concentrated in certain Philadelphia neighborhoods: West Oak Lane, Mount Airy, Wynnefield/Overbrook Park, and the Greater Northeast. And thousands more, like Americans in other cities, were moving to suburban areas, such as Abington, Cheltenham, and Lower Merion. Quite a few formerly urban synagogues, following their congregants, relocated to new suburban buildings, including Adath Jeshurun (Elkins Park, 1964) and Har Zion (Penn Valley, 1976). Congregation Beth Sholom, founded in 1918 in the Logan section of Philadelphia, moved to suburban Elkins Park in 1951 and in 1959 dedicated its new building, designed by renowned architect Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959). The postwar period witnessed an all-time high in synagogue affiliation and religious school enrollment for American Jews. Conservative congregations drew the most adherents in those years, but Reform congregations (such as Rodeph Shalom, Keneseth Israel, and Beth David in Wynnefield) also thrived. Beginning in the 1960s, significant numbers of Orthodox Jews moved to Northeast Philadelphia, Wynnefield, Overbrook Park and the western suburbs (especially Bala Cynwyd and Wynnewood), leading to the establishment of more Orthodox synagogues and schools in those areas.

Civil Rights Activism

Many Philadelphia-area Jews became activists for civil rights, working through the Fellowship Commission (established by Maurice Fagan in 1941), a unique organization that brought together Blacks and whites, Jews and Christians, to advocate for fair treatment of Black workers and for civil rights legislation throughout the 1940s and 1950s. Significant numbers of Jews also participated in the civil rights marches, sit-ins, and freedom rides of the early 1960s. Despite these sustained cooperative efforts, tensions increased between Black and Jewish communities in the 1960s, as in other cities, due to poverty, racial discrimination, and inequality in housing and employment. A flashpoint for tension was North Philadelphia, which had been predominantly Jewish and retained Jewish-owned businesses, even though by 1960, most of its residents were Black. The Columbia Avenue race riot erupted in August 1964, one of many such actions during the 1960s and 1970s in cities including Camden, Newark, Detroit, and Los Angeles. Initially sparked by a traffic dispute, the Columbia Avenue riot resulted in widespread destruction of white-owned businesses. In this era, also marked by the rise of the Black Power movement, many Black leaders chose to pursue their goals independently rather than collaborate with white supporters of civil rights.

Members of the Philadelphia Jewish community turned to other forms of activism during the turbulent 1960s and beyond. Working through the Philadelphia Soviet Jewry Council from the 1960s through the 1980s, many played key roles in the movement to free Soviet Jews. Philadelphia-area Jews sponsored Soviet Jews’ immigration to the region, which contributed to significant local concentrations of Soviet Jews. In June 1967, Jews throughout the Philadelphia area rallied and raised substantial sums in solidarity with Israel during the Six-Day War.

Philadelphia also became the birthplace of a fourth denomination in American Jewish life when the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College opened in North Philadelphia in 1968; the college moved to Wyncote in 1982. The Jewish Renewal movement, led by Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi (1924-2014) and others, emerged in Philadelphia’s West Mount Airy neighborhood in the 1970s. Reconstructionism is based on the philosophy of Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan (1881-1983), who described Judaism as “an evolving religious civilization.” Jewish Renewal characterizes itself as a “transdenominational approach to revitalizing Judaism” that emphasizes spiritual experience, meditation practices, and creative prayers.

By 1970, most of the area’s Jews lived in Center City, the Greater Northeast, the Old York Road suburbs, West Oak Lane/Mount Airy, Wynnefield, and the Main Line suburbs, as well as in Levittown and Norristown. By 1984, nearly seventy thousand Jews lived in the Greater Northeast, including large numbers of Russian Jewish immigrants; it was one of the biggest Jewish communities in the United States.

Shifting from Camden to the Suburbs

In Camden, Parkside had been the city’s foremost Jewish neighborhood, but during the 1950s and 1960s Jews joined the movement of white residents to suburban areas in South Jersey. Over the next few decades, Cherry Hill and Voorhees in Camden County, and Mount Laurel, Medford, Moorestown, and Marlton in Burlington County, emerged as prominent Jewish communities with synagogues, a Jewish Community Center, and Jewish schools. In Delaware, by the end of the twentieth century more than half the state’s Jews remained in Wilmington, about a third could be found in the Newark/Hockessin area, and a smaller fraction in southern Delaware.

In the last few decades of the twentieth century, and into the twenty-first century, a number of Jews assumed prominent positions as Philadelphia area college and university presidents and were active in city, state, and national politics. The success of Jewish political candidates in winning citywide and statewide offices indicated an acceptance of Jews, despite some undercurrents of antisemitism that surfaced during political campaigns. Several Jews from the Greater Philadelphia area prospered in Pennsylvania politics: Milton Shapp (1912-94) served as the first Jewish governor of Pennsylvania (1971-79); Arlen Specter (1930-2012) became the first Jewish U.S. senator from Pennsylvania (1981-2011); and Edward G. Rendell (b. 1944) was the first Jewish mayor of Philadelphia (1992-2000) and later governor of Pennsylvania (2003-11). By the early twenty-first century, Jews regularly held offices at all levels of local, county, and state government, with little comment about their Jewishness.

At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the estimated Jewish population of the Philadelphia Metropolitan Area, including parts of New Jersey and Delaware, was approximately 280,000. A 2018 Jewish population study by scholars Ira Sheskin and Arnold Dashefsky designated Philadelphia as the largest Jewish community in Pennsylvania and the sixth-largest Jewish community in the U.S. By 2019, the Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia reported that an estimated 351,200 Jews lived in Philadelphia, Montgomery, Bucks, Delaware and Chester Counties. According to the study, 66 percent of the Jewish adults surveyed identified as Jewish by religion, while 30 percent identified as Jewish ethnically or culturally. Of the households that responded, 26 percent identified as Reform, 26 percent as Conservative, 8 percent as Orthodox, 6 percent as Reconstructionist, 1 percent as Renewal, and 6 percent as “something else.” Some respondents reported belonging to several denominations, and 43 percent did not identify with any denomination.

Even as Jews in the Philadelphia region have participated actively in the life of the larger community, they have retained their own identity. Although some have expressed concerns about the secularization of Jewish life, and the impact of increasing intermarriage between Jews and non-Jews, Jews continue to express themselves through their religious practices, social and cultural organizations, foodways, and historical memory. Over the years, Philadelphia’s Jews have created institutions to preserve their community’s heritage within the larger context of American and American Jewish history. The Philadelphia Jewish Archives Center, established in 1972 by the Philadelphia chapter of the American Jewish Committee and the Jewish Federation of Greater Philadelphia, subsequently became part of Temple University Library’s Special Collections Research Center. (Historical archives for the South Jersey Jewish community are located at Stockton University, and the Jewish Historical Society of Delaware housed its records at the Historical Society of Delaware.) The museum now known as the Weitzman National Museum of American Jewish History opened in 1976, initially sharing a building with Congregation Mikveh Israel near Independence Mall. It moved to its own building at Fifth and Market Streets, adjacent to Independence Mall, in 2010—a location that symbolized the important role played by Philadelphia’s Jews in the larger story of the city and the nation. The Feinstein Center for American Jewish History, founded at Temple University by American Jewish historian, civic activist, and community leader Murray Friedman (1926-2005) in 1990, supports research and publication in the field. Jewish Studies programs at universities across the region, as well as Holocaust studies in schools, further reminded Jews and others of the significance of Judaism and the Jewish experience. The work of these and other organizations and institutions celebrate the many contributions made by Philadelphia-area Jews to their neighborhoods, communities, region, and nation.

Reena Sigman Friedman is Associate Professor of Modern Jewish History at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, as well as Adjunct Professor of Jewish History at Gratz College. She is the author of These Are Our Children: Jewish Orphanages in the United States, 1880-1925, several encyclopedia entries, book chapters, and numerous scholarly articles. She lectures widely on topics relating to various aspects of American Jewish History. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2024, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- “From Philadelphia to the Front" video (USA)

- “50 Children: The Rescue Mission of Mr. and Mrs. Kraus" documentary (HBO Documentary Films)

- Jewish Heroes in the Revolutionary War (Decalogue Society of Lawyers)

- Jews for Slavery, Jews against Slavery (Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation)

- Jewish Foster Home and Orphans Asylum of Philadelphia (Germantown Crier)

- Commerce and Community: Philadelphia's Early Jewish Settlers, 1736–76 (The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography)

- Sabato Morais and Social Justice in Philadelphia, 1858-1897 (Shofar)

- Jews in America: The History of the Philadelphia Jewish Federation (Jewish Virtual Library)

- Over 100 Years of Active Jewish Life in Delaware (Jewish Historical Society of Delaware)

- United States Jewish Population (American Jewish Year Book 2018)