Lewis and Clark Expedition

By Luke Willert

Essay

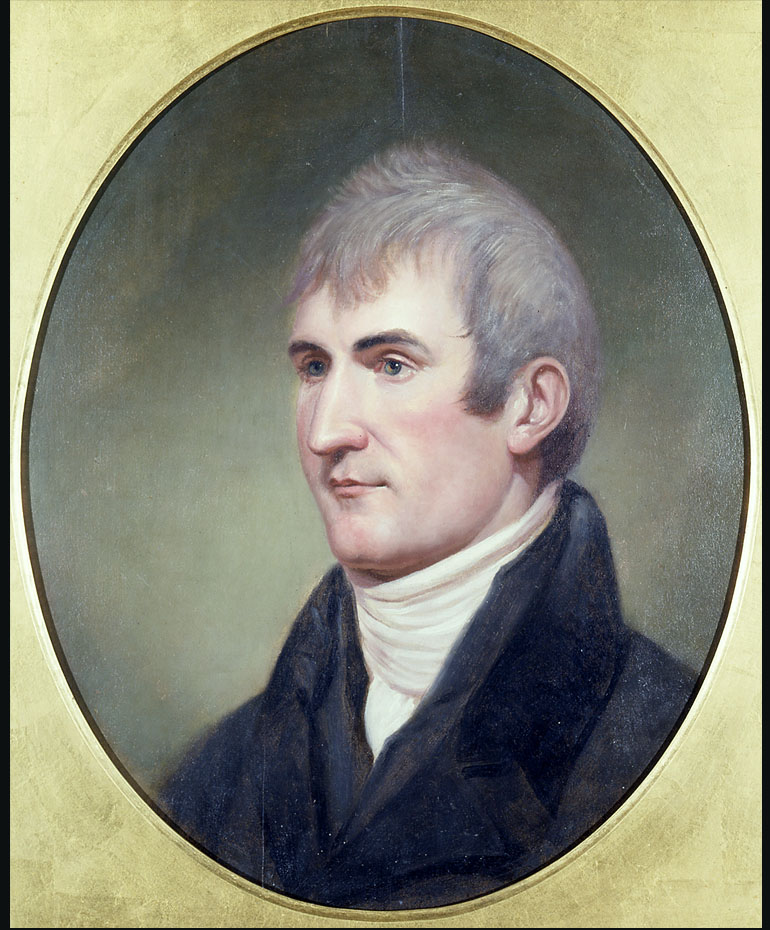

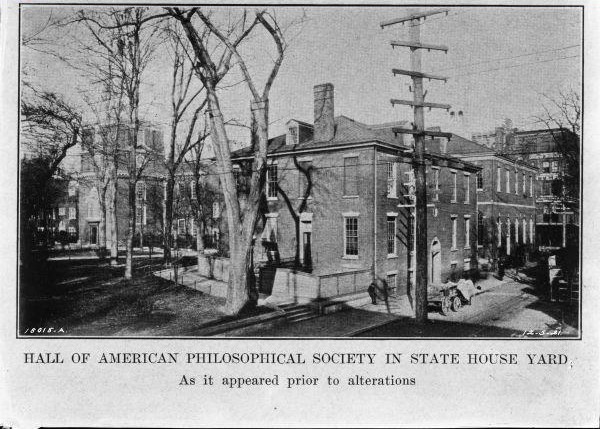

On a November day during the severe winter of 1805, a parcel containing over sixty plants, rocks, and fossils arrived at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. Collected by Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809), these were specimens from the Corps of Discovery Expedition (1803-1806), the western journey of Lewis and William Clark (1770-1838). While the explorers became renowned for crossing the Rocky Mountains and canoeing over the Columbia River, the inspiration and education for their travels came from Philadelphia’s libraries and scientific societies.

For several decades, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) had planned a national expedition into the West. After winning the presidential election of 1800, he put the idea into motion. Exploration became particularly important after the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, which added to the nation extensive and unmapped lands west of the Mississippi River. Jefferson’s fundamental vision for the continent’s future—an American “empire for liberty”—rested upon the gradual settlement of this enormous space by the nation’s farmers and their growing families. The nation must expand its borders outwardly, he and other leaders believed, if successive generations were to remain as independent as the Revolutionary founders. More and more western land was the only antidote against the corruption fostered by the overcrowded cities and plantations of the East. One primary function of early American science, then, was to aid this national growth by cataloguing the strange, often dangerous natural world of the West so that it might quickly be subdued and transformed. In the same way, U.S. ethnologists learned about Indians as a step towards the nation taking their land. Nineteenth-century explorers traveled, collected, and wrote with an eye towards ordinary American citizens eventually following them and staying put as settlers. Because Philadelphia was the original scientific capital of the United States and the intellectual base of its earliest expeditions, the city played an important role in the nation’s colonization of the West.

Jefferson chose as leader of the expedition his private secretary Meriwether Lewis, who was experienced in both the study of natural history and the grit of rustic survival. For his partner, Lewis selected William Clark, a friend from Kentucky who had served in several military campaigns against American Indians. The president’s specific goals for their journey included identifying a route to the Pacific Ocean, making diplomatic contact with western natives, and gaining geographic knowledge of the vast and mysterious expanse.

Before they went west, Lewis and Clark turned to scientists in Philadelphia to help shape their mission. During the Revolutionary era and early republic, Philadelphia was the place where the nation’s best naturalists named new specimens and published their books. Then, during and after the journey, Philadelphia scientists received, organized, and disseminated the explorers’ western findings.

Lewis purchased most of the supplies in Philadelphia: camping gear, clothing, books, trading goods, food, containers, guns and ammunition, scientific instruments. He learned from the city’s naturalists how to locate new specimens and preserve them. Before the expedition, Lewis had come to Philadelphia in May 1803 to learn. At the University of Pennsylvania, Benjamin Smith Barton (1766-1815) taught him about botanical collecting and the French presence in Louisiana. Lewis then learned about medicines and diseases from Benjamin Rush (1746-1813), and animals and fossils from Caspar Wistar (1761-1818). Lewis visited the surveyor Andrew Ellicott (1754-1820) in Lancaster for lessons in geography, and he almost certainly toured the museum of Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), who had recently put the world’s first excavated mastodon skeleton on display. Famously, Jefferson suggested to the explorers that they might encounter a living one in the field, the idea of extinction being then uncertain.

After completing the expedition in 1806—over 7,000 miles back and forth between the United States’ western terminus St. Louis and the Pacific Ocean—Lewis returned to Philadelphia and bequeathed many of his western treasures to Peale. Peale then displayed the objects, mostly diplomatic gifts from western Indians, in a special exhibit and painted portraits of both Lewis and Clark that remain on display at Independence National Historical Park. (Many of these objects were lost over the years, while others ended up in Harvard University’s Peabody Museum.) Philadelphians also published the journals of Lewis and Clark, including Lewis’ posthumous official journal in 1814. Even a forged account of the expedition from 1809, created by a shady printer named Hubbard Lester, came out of Philadelphia. Whether Lewis and Clark are remembered as national heroes or imperial soldiers, their project connected the extraordinary scientific world of Philadelphia with the extraordinary American West.

Luke Willert is a graduate student in the History Department at Harvard University. He writes about the American West and environmental history. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Philadelphia Chapter Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation

- Lewis and Clark's Herbarium

- Meriwether Lewis in Philadelphia

- Lewis & Clark in Philadelphia (Part II): The Map’s the Thing

- Meriwether Lewis (1774-1809) Historical Marker

- Schuylkill Arsenal Historical Marker

- The Lewis and Clark Expedition Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)