Loyalists

Essay

During the American Revolution, Loyalists, or “Tories” as Patriots called them, included prominent Pennsylvania political and religious leaders as well as many less affluent individuals from the state’s Quaker and German pacifist communities. A large number of “neutrals” also struggled with increasing difficulty to remain uninvolved in the conflict. Religion, ethnicity, economic status, and local concerns influenced decisions to back the rebellion, remain loyal to Great Britain, or stay neutral. Many initially supported Patriot resistance against Parliamentary taxation but gradually shifted their allegiance after protests turned into war and formal independence.

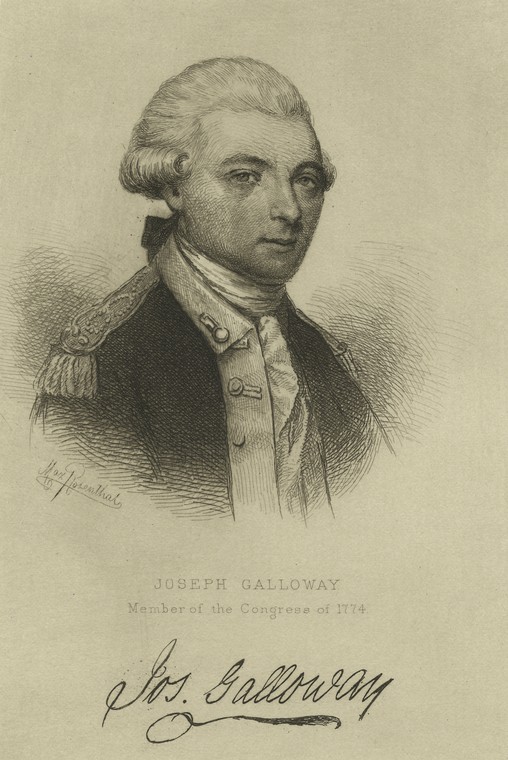

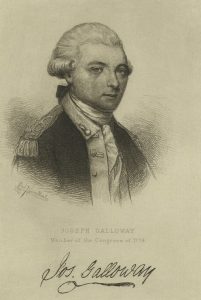

Historians estimate that 15 to 20 percent of white colonial men actively aided the British in their attempts to suppress the Revolution. Over the course of the war, about 30,000 colonials bore arms for Britain. Many prominent Pennsylvania leaders ultimately sided with the Crown, including former Philadelphia mayor William Allen (1704-80), Pennsylvania Assembly Speaker Joseph Galloway (1731-1803), and Anglican Rector of Christ Church Jacob Duché (1737-1798), who had given the blessing for the first Continental Congress. Former New Jersey Assembly Speaker Cortlandt Skinner (1727-99) became a British brigadier general, commanding the Loyalist “New Jersey Volunteers.” New Jersey Governor William Franklin (1731-1813), son of Benjamin Franklin (1706-90), helped establish a Board of Associated Loyalists, coordinating Loyalist guerilla attacks throughout the mid-Atlantic region. Three thousand Philadelphia Loyalists left the city with the army of General William Howe (1729-1814) at the end of the British occupation in 1778. Continentwide, by the war’s end, 60,000 to 80,000 colonials chose exile rather than remain under the new American governments.

Many enslaved African Americans gave their support to the Loyalist side, while others fought for the Patriots. When offered freedom in exchange for war service, around 20,000 slaves escaped to the British lines. Although most were from the southern colonies, at least sixty-seven came from the Philadelphia area. Personal liberty was an obvious motive, but there is also evidence that some slaves were actively cheering for a British victory. On December 14, 1775, the Evening Post alleged a Philadelphia slave had threatened a white woman, “Stay you d—-d white bitch ’till Lord Dunmore and his Black regiment come, and then we will see who is to take the wall.”

Ethnicity and religion often guided citizens’ political allegiance in the Philadelphia region. Many Quaker and German pacifists tended toward neutrality or Loyalism (as did the Anglicans), while Baptists and Presbyterians were more likely to lean Patriot. The Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) forbade military service and any aid to violent rebellion; while many Friends had initially supported the resistance movement, they pulled away as colonial protests grew more violent. Many Quakers believed that to keep their faith they must not pay war taxes, pay fines in lieu of military service, swear oaths of allegiance, or aid military efforts in any manner. By 1775, Monthly Meetings throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware removed members from their rolls for overt support of the rebellion. After the Declaration of Independence, when the new state governments demanded loyalty oaths and tax payments, the Quakers’ situation became worse. A small group, the “Free Quakers” who supported the rebellion, splintered from the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting to form their own congregation, gathering in private homes before they built a meetinghouse in 1783.

“Peace Germans”

Members of Amish, Brethren (Dunker), Mennonite, Moravian, and Schwenkfelder congregations had similar problems. On the eve of the Revolution, about 10,000 members of these German pacifist sects called Pennsylvania home. These “Peace Germans” believed that God alone possessed the right to overthrow a legal government, which rendered them unable to swear loyalty to any revolutionary government—until final victory proved God’s will. Like the Quakers, the Peace Germans were disappointed because the state’s new government abandoned the policy of religious toleration that had drawn them to Pennsylvania. The Schwenkfelder Petition to the Pennsylvania Assembly (October 1777), signed by approximately 1,500 people from various German pacifist denominations, reminded the Assembly that “the only reason for our journey” to America was to “become partakers of the benefits of the just and well-known religious freedom as well as civil rights in Pennsylvania.” As far as can be determined, most of the Peace Germans were truly neutral, as opposed to politically committed to a British victory.

The shift in allegiance toward the British side was often gradual. Many future Loyalists, including prominent Pennsylvania leaders, supported some aspects of the Patriot resistance until escalating turbulence and the Patriots’ path toward independence led them to withdraw their support. As Royal Governor of New Jersey, William Franklin refused to let the Royal Charlotte unload stamped paper in 1765, on the premise that he could not guarantee the cargo’s safety; he later joined celebrations when the Stamp Act was repealed. One of two Quakers later hanged for treason, John Roberts (1721-78), signed a resolution condemning the 1774 Boston Port Act as “unconstitutional; oppressive to the inhabitants of that town; dangerous to the liberties of the British Colonies.” Joseph Galloway took a seat in 1775 at the First Continental Congress, but later led the civilian government during the British occupation of Philadelphia.

For many Philadelphians, the outbreak of warfare decided them; for others, the Declaration of Independence was a step they were not prepared to take. After July 4, 1776, many Loyalists pointed to the Declaration as proof Patriot leaders had been deceptive in their true aims. Galloway said the Declaration of Independence confirmed his longstanding suspicions: the radicals “had deceived the people from the beginning … and that notwithstanding all their solemn professions to the contrary, they ever had independence in their view.”

For those who sought to remain aloof from the struggle, neutrality and noninvolvement became more difficult after 1776.The disastrous Mid-Atlantic campaign resulted in substantial recruits for the British that increased Patriot paranoia, leading to harsh anti-Loyalist laws. On the eve of the Battle of Trenton, the British reported that 4,836 colonists of New Jersey had taken oaths of allegiance. George Washington (1732-99) wrote: “The conduct of the Jerseys has been most infamous; instead of turning out to defend their country and affording aid to our Army, they are making their submissions as fast as they can” (December 18,1776). By the Revolutionary War’s midpoint, more New Jersey men were serving among the ranks of the British army than in the Continental forces. In response, state legislatures (including Pennsylvania’s), passed laws that required oaths of allegiance, or “test oaths,” to the new governments. Those who refused to swear (whether from political or religious scruples) were deemed “nonjurers,” subject to substantial fines and deprived of the right to vote, hold office, serve on juries, sue for debts, transfer real estate, or even hold some occupations. While few pacifists were imprisoned, the confiscations and fines ruined many families financially.

Occupation of Philadelphia

Rebel reprisals in Pennsylvania were harshest immediately before and after Philadelphia’s nine-month occupation in 1777-78. On the eve of the British attack on the revolutionary capital, fear that spies and collaborators would aid the British led Pennsylvania’s legislature, on the advice of Congress, to arrest forty-one Philadelphians judged “disaffected to the American cause.” Of these, twenty-two Quakers were banished to the frontier town of Winchester, Virginia, where they remained for eight months until repeated petitions and complaints brought about their release. Two died before their discharge in April 1778.

After Howe’s forces occupied Philadelphia on September 23, 1777, many formerly neutral and apolitical Philadelphia residents socialized openly with British officers, while area farmers supplied provisions to British and Hessian armies. Patriot anger reached a crescendo after the British staged the Meschianza, an elaborate pageant to honor General Howe before his departure for London. The combination regatta, jousting tournament, and formal dinner cost over £3,000 pounds, and feted the elite women of Philadelphia, some from known Loyalist families and others who had previously claimed neutrality.

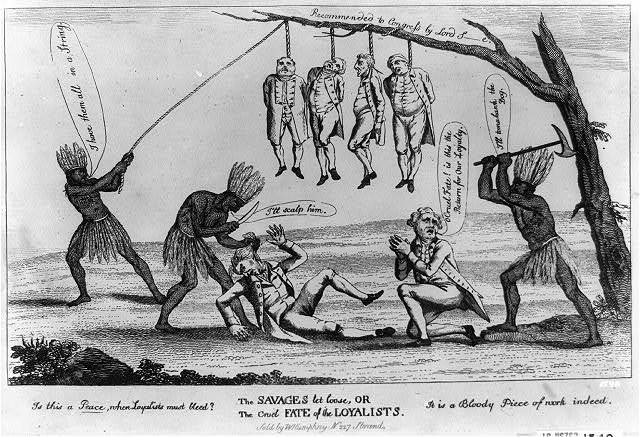

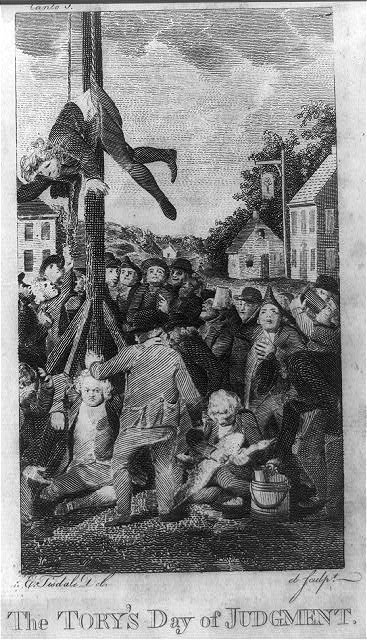

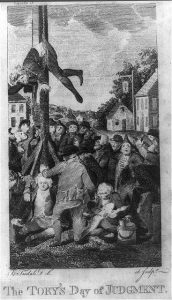

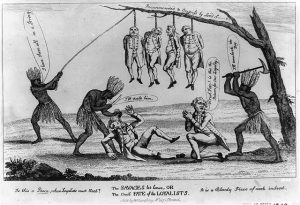

The end of the British occupation unleashed another wave of popular fury at such “Tory” collaborators, as the Pennsylvania government arrested 638 Philadelphians on suspicion of treason. More than one hundred people lost their property. Two of the arrested, Quakers John Roberts and Abraham Carlisle (?-1778), were charged with collaborating with the British and hanged. Carlisle had been a British gatekeeper, issuing passes out of the city; Roberts allegedly acted as a guide for the British raiding parties in the nearby countryside. While the two men had trials, unlike the Winchester exiles, the evidence against Roberts in particular seemed flimsy, and the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania received numerous appeals for clemency. Regardless, both men were executed on November 4, 1778. More than four thousand Philadelphians attended the burial march.

Following the 1778 British military reversals (particularly Saratoga and the evacuation of Philadelphia), many mid-Atlantic Loyalists castigated the British for their mild prosecution of the war and advocated a much harsher line. While the British military made no real systematic attempt to organize the Loyalists into regiments until the Southern campaign, Loyalist guerilla fighters wreaked havoc in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Loyalist militia conducted nighttime raids, burning farms and houses and kidnapping Patriot leaders. William Franklin’s Associated Loyalists worked as an autonomous military organization with the design of “annoying the sea coasts of the revolted provinces and distressing their trade.” In some areas, the collapse of civil society led to banditry by militias of both sides, especially in the Pine Barrens of South Jersey and along the New York-New Jersey border.

The end of the war stunned many Loyalists, who still expected a British victory, as did the terms of peace treaty that followed. The 1783 Treaty of Paris made few provisions to protect Loyalists or return their property. Its Article 5 promised only that “Congress shall earnestly recommend” the restitution of confiscated properties. State governments (not Congress) had conducted most confiscations, and the Articles of Confederation granted the national government little power to compel state compliance. Legal proscriptions against the Loyalists took years to repeal. The Test Laws were first challenged in the Pennsylvania Assembly in 1784, and finally repealed two years later. In many places, Loyalists attempting to return to their communities experienced popular animosity. A mass meeting of Easton, Pennsylvania, residents protested the return of Loyalists who fought with the Indians, accusing them of having wet “their hands in the blood of our unprotected countrymen.” In New Jersey, returning Loyalists were attacked with tar and feathers. Some German pacifists continued to feel unwelcome years after the war’s conclusion. During the 1780s and 1790s, several Bucks County Mennonite congregations left to establish new communities in Ontario, Canada. While most states (including Pennsylvania) repealed anti-Loyalist laws before 1788, Pennsylvania’s “Black List” of individuals subject to arrest or confiscation was still in circulation as late as 1802. Such signs of continuing resentment toward both Loyalists and neutrals indicate that the divisions created by the Revolution persisted long after the peace.

Shannon E. Duffy received a B.A. from Emory University, an M.A. from the University of New Orleans, and a Ph.D. from the University of Maryland. Currently a Senior Lecturer in Early American History at Texas State University, her manuscript The Twin Occupations of Revolutionary Philadelphia explores the psychological effects of the British occupation of Philadelphia under General William Howe, as well as the American reoccupation of the city eight months later under the command of General Benedict Arnold. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Class Warfare on Arch Street (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The British Campaign for Philadelphia and the Occupation of Valley Forge in 1777 (National Park Service)

- "The Philadelphia Campaign: Chapter Three, The Occupation of Philadelphia." (ExplorePAHistory)

- James Kirby Martin Interview (Mount Vernon Online Exhibit on Benedict Arnold)

- "Major André & the Meschianza." (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- John J. McLaughlin, "Black Loyalists in the American Revolution." (History News Network)

- Kacy Tillman, "What is a Female Loyalist?" Common-place 13, no. 4 (Summer 2013)