Lutherans and the Lutheran Church

By Karl Krueger

Essay

Lutherans came early to the Philadelphia region as economic opportunities provided them with possibilities that their homelands could not offer. Once settled, they worked to transplant their spirituality in their new homeland. To that end, they established congregations, a synod, social ministry organizations, and a seminary that ministered to them and their descendants. The presence of an established Lutheran network after the Civil War provided new arrivals from Europe, Africa, and the Danish West Indies (U.S. Virgin Islands) and Puerto Rico with a haven and community that fostered their faith. While the number of congregants declined over time, the Lutheran church maintained a visible presence in Greater Philadelphia with its social services, ministries in a variety of languages, and a seminary to train its leaders.

Lutheranism started in Europe when Martin Luther (1483-1546), an Augustinian monk, questioned the abuse and ultimately the validity of indulgences in the ministry of the Roman Catholic Church in 1517. When he persisted in his criticisms of the church, he was declared a heretic, excommunicated by the Pope in 1521, and condemned as an outlaw by Emperor Charles V that same year. Further questioning led Luther to develop an evangelical theology shaped by three understandings: that justification before God is a gift of grace rather than a reward for good works, that God is revealed in the law and the gospel, and that divine truth is often made known in unreasonable unlikely places such as the manger and the cross.

Evangelical Lutheran teachings were defended as apostolic and catholic in the Augsburg Confession (1530) and its Apology (1531) that were written by Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560), a layperson and professor of Greek at the University of Wittenberg. Fearing the confiscation of their lands by Roman Catholic leaders, Lutheran rulers created the Schmalkaldic League in 1531 and eventually went to war in 1546 and again in 1552 with the imperial forces of Charles V. At the end of the war in 1555, rulers in the Holy Roman Empire acknowledged the Lutheran church as a legitimate confession of the Christian faith. By the close of the sixteenth century, Lutheran territorial churches had been established in central and northern Europe.

Lutherans arrived in the Delaware Valley in 1638 when a small contingent of Swedes landed and established the colony of New Sweden along the Delaware River. While this settlement fulfilled the dream of empire of King Gustavus Adolphus (1594-1632), who wanted a Swedish colony in the New World between the Dutch in New Amsterdam and the English in Virginia, the settlers themselves sought economic advancement. Johan Björnsson Printz (1592-1663), appointed governor by the crown, arrived in 1643 with the Rev. Johan Campanius (1601-83). A graduate of Uppsala University, Campanius served the small Swedish settlements between Wilmington (Christina) and the later site of Philadelphia (Wicaco) and those in New Jersey.

Algonquin-Swedish Dictionary

Besides providing pastoral care, Campanius learned Algonquin and started to translate Luther’s Small Catechism for the area’s indigenous people, the Lenape. It was an innovative endeavor because Campanius expanded Luther’s explanations to address life in the Delaware Valley. He returned to Sweden in 1648, completed his translation of the catechism and compiled a small Algonquin–Swedish dictionary. Both were published in one small octavo volume in Stockholm at the expense of the Crown in 1696 and sent to Swedish pastors in the Delaware Valley whose congregations by that time worshipped in brick churches like Gloria Dei (Old Swedes’) in Philadelphia. The colony was absorbed by the Dutch and then the English, but Lutheranism continued, albeit with few members and without official sanction as a state church.

German Lutherans from the Palatinate who migrated to British North America in the eighteenth century wrote the next chapter of Lutheranism in the Philadelphia region. Unlike the Mennonites, Amish, and radical German pietists who came to Penn’s “Holy Experiment” for religious freedom, German Lutherans arrived in large numbers for economic reasons, specifically the promise of inexpensive land that allowed them to establish farms and raise families. They preserved their premigration piety by organizing congregations and worshiping in German in homes, rented rooms, and barns.

The first Lutheran ordained to the pastorate in the Western Hemisphere was Justus Falckner (1672-1723). He arrived with his older brother, Daniel (1666-1741), in 1700 to work in his brother’s real estate venture, the Frankfort Land Company that settled Germans in Falckner’s Swamp (New Hanover) in Montgomery County and Germantown. Justus left the business because he felt called to serve the church. His ordination was held in Philadelphia’s Swedish Lutheran church, Gloria Dei, on November 24, 1703. The event was multicultural. On that day, Swedish Lutherans ordained Justus Falckner, a German, so he could serve Dutch Lutherans living in the English colony of New York. So that everyone could take part in the ordination and the Eucharist that followed, they conducted the service in Latin, Swedish, and German.

The Lutheran experience in the Delaware Valley owed much to Henry Melchior Mühlenberg (1711-87). A Hanoverian by birth, he studied theology at Göttingen University and finally in Halle. He arrived in Philadelphia on November 25, 1742, to serve three congregations and documented his forty-five years of service in journals that were copied and sent to the Royal Court Chaplain in London and the administrator of the Francke Foundations in Halle. By maintaining these international contacts, Mühlenberg received funding, books, medicines, and thirteen European-trained clerics for the growing Lutheran church in greater Philadelphia. By the time of his death in 1787, he had written a liturgy (1748), organized a Ministerium (1748), drafted a constitution for St. Michael’s Church in Philadelphia (1762), and edited a hymnal (1786). These texts reformatted governance and worship for the American context and allowed the Lutheran church to move with the expanding frontier. By 1848, the centennial of its founding, Mühlenberg’s Ministerium of Pennsylvania and Adjacent States had grown to 222 congregations with sixty-seven pastors and 41,739 members; and by 1898, 150 years later, it consisted of 505 congregations, 337 pastors, and 191,257 members.

Shared Governance

The constitution for St. Michael’s Lutheran Church in Philadelphia (1762) was a milestone in that it established shared governance in the congregation’s administration. It was groundbreaking because it inverted the traditional European paradigm that had authorized the landed gentry and city councils to oversee congregations. Fourteen years before the Founding Fathers wrote a Declaration of Independence, Mühlenberg, a German immigrant, drafted a “declaration of dependence” in which the church would be a partnership between clergy, laity, and the Ministerium. Mühlenberg read the constitution on Monday, October 18, 1762, in St. Michael’s, after which he and the parishioners signed the document that enshrined their voluntary allegiance and individual belonging as fundamental elements of Lutheranism in America. Its principles of cooperation continued to guide the Lutheran Church in the twenty-first century.

Besides pastoral service and overseeing the Ministerium, Mühlenberg supervised the construction of new sanctuaries in Philadelphia, Trappe, and New Hanover. The Philadelphia churches were St. Michael’s and Zion Lutheran. St. Michael’s at Fifth and Cherry Streets, dedicated in 1748, could seat six hundred worshippers. The steady influx of German Lutheran immigrants, however, called for a larger sanctuary in the city. Robert Smith (1722-77), who designed Carpenters’ Hall, drew up the plans for Zion Lutheran Church at Fourth and Cherry Streets. The spacious church, dedicated in 1769, seated 2,500 people comfortably and became the home of a large pipe organ built by David Tannenberg (1728-1804). The largest auditorium in the city, it subsequently hosted several significant services: the Municipal Memorial Service for Benjamin Franklin in 1791, a series of musical concerts with President and Mrs. George Washington in attendance on January 8, 1791, and the Congressional Memorial Service for President Washington on December 26, 1799. Zion Lutheran was demolished in 1869. St. Michael’s in Philadelphia was razed in 1872.

Lutherans built not only churches but also an infrastructure of charitable institutions, hospitals, schools, and mutual aid societies that reinforced and reflected their values of community and service and extended their influence in the region. In the nineteenth century, Lutherans responded to pressing social needs by founding the Germantown Home for Orphans (1859) and the German Hospital (1860). The hospital moved to Girard and Corinthian Avenues and was expanded in 1884 by John Lankenau (1817-1901). At Lankenau’s invitation, seven German Lutheran deaconesses arrived from Iserlohn to staff and administer the institution. A motherhouse for the deaconesses and the Mary J. Drexel Home for the Aged were constructed alongside the hospital in 1888. From this base the deaconesses coordinated their ministries such as the Kensington Dispensary for the Treatment of Tuberculosis and River Crest, a home in Phoenixville for children exposed to tuberculosis. Although these institutions closed, their names lived on in KenCrest, which continued to serve in the spirit of the German Lutheran deaconesses. In 1917, on the eve of the First World War and the centennial of Lankenau’s birth, the German Hospital was renamed Lankenau, and in 1953, it moved to Wynnewood and eventually became a secular institution with no formal association with the Lutheran church.

In the 1860s, as Lutherans established a charitable infrastructure, they confronted slavery and Americanization. On the issue of slavery, southern Lutherans defended the institution and formed the General Synod of the South in 1863. Slaves and free persons of color sat in separate galleries or rear pews in Lutheran churches. Lutherans in the Delaware Valley argued against slavery and commissioned the Rev. Jehu Jones (1786-1852), the first African American Lutheran pastor, to work as a missionary to African Americans in the area in 1833. Jones, originally from South Carolina, was ordained in New York City in 1832 to serve in Liberia. When funds for Liberia failed to materialize, Jones and his family moved to Philadelphia and within a year organized St. Paul’s, the first independent African American Lutheran church in America. The sanctuary constructed at 310 S. Quince Street in 1834 was dedicated in 1836, but only housed the small congregation until 1839, when unpaid bills forced its sale. Jones then met with the congregation in a room on Seventh Street below Lombard until 1851, when it disbanded. The Ministerium’s limited resources, the disruption of the Civil War, and the surge of immigrants from central and northern Europe after 1865 ended organized outreach to the African American community in the nineteenth century. At the national level postwar bitterness prevented northern and southern Lutherans from reuniting, and regional separation continued until the creation of the United Lutheran Church in 1918.

In America, a Church Divided

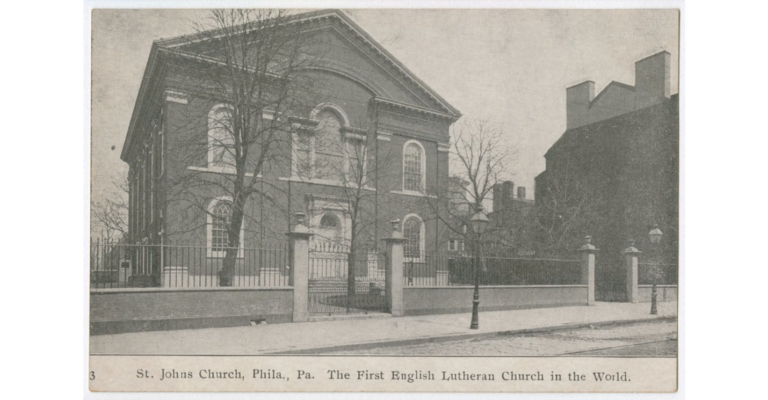

Like slavery, the role of the Augsburg Confession in America divided Lutherans. The drive to assimilate led some Lutherans to propose changes to the traditional teachings of this foundational document. They believed these modifications would fit the Lutheran tradition more neatly within the American Protestant churchscape and its anti-Catholic ethos. “American Lutheranism” received its classic presentation in a pamphlet by Samuel Simon Schmucker (1799-1873) entitled The Definite Platform. Published anonymously in 1855, it proposed abolishing practices that American Protestants regarded as Roman Catholic: private confession and absolution, the ceremonies of the Mass, baptismal regeneration, and the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Schmucker also wanted Lutherans to accept Sunday as the sabbath, along with the Puritan understanding that transferred Old Testament expectations to that day. Lutherans worshipped and rested on Sunday, the first day of the week, because it celebrated Christ’s resurrection. Accepting it as the sabbath with mandated restrictions enforced by civil law contradicted Luther and the Augsburg Confession (Article 28). Schmucker’s proposal provoked a heated response from traditional Lutherans in the United States who argued that classical Lutheranism rejected Sunday as the Sabbath and embraced the practices named in The Definite Platform as catholic (universal) and essential for ministry. In the Delaware Valley the majority of pastors in the Ministerium of Pennsylvania defended traditional Lutheranism, helped create the General Council of the Lutheran Church in 1867, and designated their newly organized seminary in Philadelphia (1864) as their educational center.

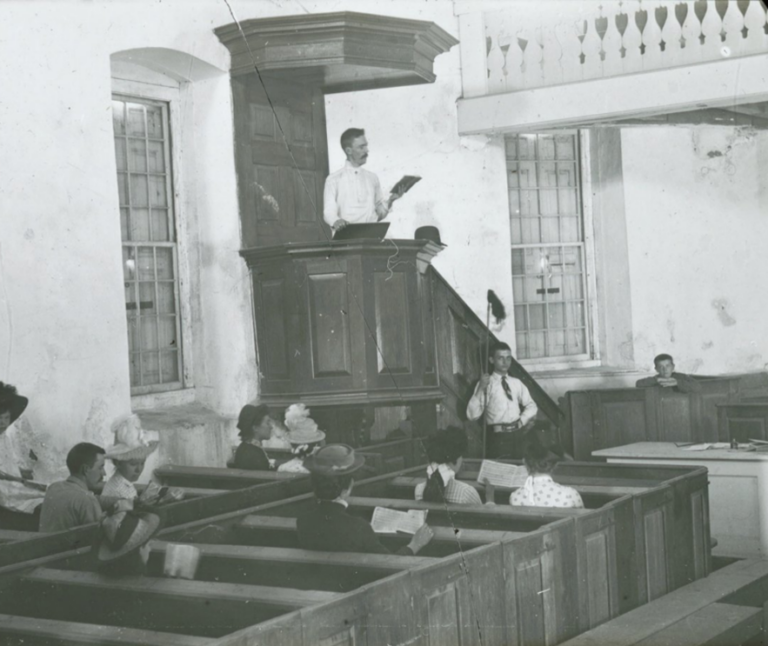

The seminary was bilingual and trained pastors to serve both German- and English-speaking congregations in greater Philadelphia. At first classes met in the Lutheran Bookstore on North Ninth Street, later in a building across from Franklin Square, and starting in 1889 in Mt. Airy at Germantown Avenue and Allens Lane on a property that had belonged to Chief Justice William Allen (1704-80). The faculty became known for their scholarship in liturgical studies, biblical scholarship, and Lutheran confessional understanding.

Lutheran worship in the twentieth century remained loyal to its European heritage. With the advent of the First World War and American suspicion of everything foreign, particularly anything German, worship services in German were temporarily suspended. After the war, however, congregations in the Delaware Valley returned to their mother tongues and conducted worship in English, German, Slovak, Swedish, Norwegian, Latvian, and Estonian well into the twentieth century. As the descendants of immigrants, Lutherans continued to welcome new immigrants into their churches and helped establish Liberian and Hispanic congregations in greater Philadelphia. In the 1960s Lutherans created the Center City Lutheran Parish [CCLP] that organized ministries in twenty-five Lutheran churches in Philadelphia’s inner-city neighborhoods. Unlike the Jehu Jones mission to African Americans that ended because of a lack of resources, CCLP received synodical support.

Most Lutherans in Philadelphia and surrounding counties belonged to the General Council, which was guided by the Mühlenberg tradition. That spirit of partnership led the General Council to unite with other Lutheran bodies whose roots went back to Mühlenberg, specifically the General Synod and the United Synod of the South. They came together in 1918 to form the United Lutheran Church in America (ULCA). Cooperation with like-minded Swedish, Finnish, and Danish Lutheran churches in America led to establishment of the Lutheran Church in America (LCA) in 1962, with its publication house, Fortress Press, at 2900 Queen Lane in Philadelphia. Another merger occurred in 1987-88 when the three major national Lutheran churches in the United States, one of which was the LCA, created the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA). While a few congregations in the area belong to the Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod, the Wisconsin Synod, the Evangelical Lutheran Synod, or the North American Lutheran Church (NALC), the majority were in the ELCA’s Southeastern Pennsylvania Synod. In 2017, the year that marked the 500th Anniversary of the Reformation, the Lutheran seminaries in Gettysburg and Philadelphia merged to form the United Lutheran Seminary.

Modern Challenges

Like other mainline Protestant churches in the United States, Lutheran churches suffered from declining membership by the late twentieth century and a shortage of clergy, and faced a host of questions about the place of women, LGBT clergy, and marginalized groups within the church. Lutheran responses included the LCA approving the ordination of women to the ministry of Word and Sacrament beginning in 1969, and in the ELCA with the election of the Reverend Patricia Davenport (b. 1955) as a synodical bishop in 2018. Davenport was the first female African American to be elected to this position within the ELCA. In August 2009, the ELCA moved beyond the mandated celibacy for LGBT clergy stipulated in its Visions and Expectations (1990) and approved the ordination and ministry of individuals in same-gender, lifelong, monogamous relationships.

In the greater Delaware Valley, the Lutheran story is enshrined in Gloria Dei (Old Swedes’ Church) in Society Hill; in Augustus Lutheran Church and the Mühlenberg homes in Trappe, Pennsylvania; the Lutheran seminary on Germantown Avenue, and two statues cast by the noted Swiss-American sculptor J. Otto Schweizer (1863-1955), one of Peter Mühlenberg (unveiled in 1911) standing on the grounds of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and one of Henry Melchior Mühlenberg (unveiled in 1917). The Mühlenberg statue was intended for Fairmount Park but came to the seminary’s property on Germantown Avenue due to the anti-German sentiment of the First World War.

Although Lutherans in the greater Delaware Valley largely assimilated, their ethnic heritages have lived on in ancestral hymns translated into English and the parish cookbooks published over the years. By 2020, over 70,000 Lutherans in the greater Philadelphia area worshipped in 154 congregations.

The Rev. Karl Krueger, Ph.D. Professor Emeritus, History of Christianity, is Director Emeritus of the Krauth Memorial Library of the former Lutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.