Missionaries

Essay

The Philadelphia region historically produced fewer missionaries than other areas of North America. Through at least the early twentieth century New Englanders and southerners dominated the organized efforts of Christian churches to send out evangelists to convert others to the faith. Ironically, William Penn’s decision to make Pennsylvania a Holy Experiment in religious tolerance may explain why Philadelphia did not experience the flowering of missions seen to its north and south, as fewer settlers were inclined towards persuading others to adopt their religious perspective. Even so, the area’s rich religious heritage provided impetus for some missionary efforts.

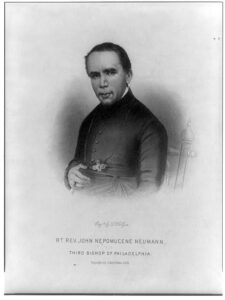

The earliest Christian missionaries in the Americas worked among Native Americans, though efforts in British North America were muted compared to those of French Jesuits in the Great Lakes region and Spanish priests establishing missions throughout New Spain. Among the Swedes who settled Fort Christina in 1638 at present-day Wilmington, Delaware, Lutheran minister John Campanius (1601-83) learned the language of the area’s Delaware Indians and sought converts using a translated catechism, making him the region’s first Christian missionary. A century later David Brainerd (1718-47), a young Presbyterian from Connecticut who was influenced by the New Light theology of the Great Awakening, procured a commission as Native American missionary and in the course of three years’ work with Delawares near present-day Crosswicks in central New Jersey, baptized and organized a community of over 130 converts before succumbing to tuberculosis in 1747. Although many persecuted religious groups coming to colonial Pennsylvania sought to insulate their members from the corrupt or bruising influences of wider society, the Moravians were committed to missions work, preaching to Native Americans and establishing towns on the Pennsylvania frontier that welcomed converts. The most influential Moravian missionary of the eighteenth century was David Zeisberger (1721-1808), a native of Saxony who migrated first to Georgia before helping found Bethlehem in 1741. From there, he ventured out to Native peoples on the Pennsylvania and Ohio frontiers. Zeisberger learned Iroquoian and Algonquian languages, producing dictionaries and religious tracts in each and establishing several communities of converts. Efforts like Zeisberger’s laid early groundwork for continued Christian missions to Native peoples throughout North America as European-American settlement expanded west in subsequent centuries.

In the same era Henry Mühlenberg (1711-87) came from Germany to minister to Lutherans in North America. Landing in Philadelphia in 1742, he traveled from his base in New Providence up and down the Atlantic seaboard, preaching to European settlers in multiple languages and successfully consolidating the Lutheran denomination in North America. Anglican missionaries sent to Philadelphia by the British Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts were less successful. Charged by the Church of England with countering dissidents’ influence in the British colonies, they struggled to find willing converts in a colony dedicated to religious tolerance, and many were forced to close their missions during the American Revolution to avoid persecution.

Missionary Influences on the Church

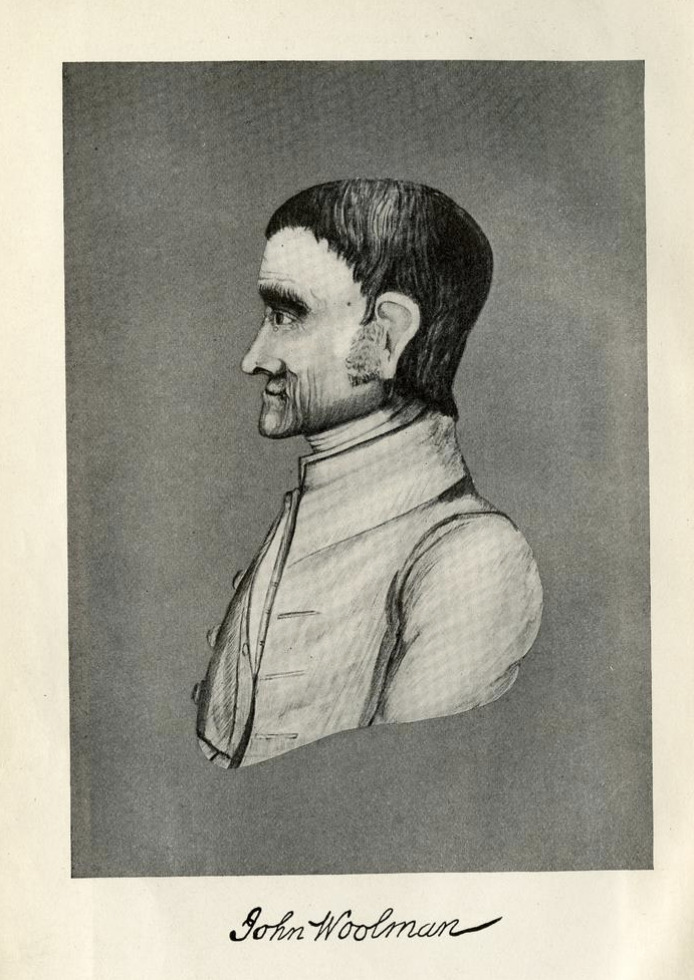

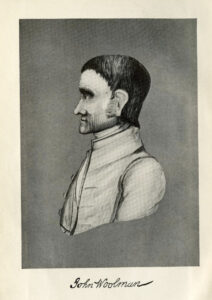

Missionaries often have moved their home churches toward new theological and political positions, as in the case of John Woolman (1720-72), the best-known missionary from the middle colonies. A merchant and tailor born in 1720 to Quaker farmers in Mt. Holly, New Jersey, Woolman abandoned his businesses to become a full-time reformer after being asked several times to sign a bill of sale or probate transfer of slaves. The experience moved him to embrace abolition, a cause he made his mission for the remainder of his life. In 1746, Woolman traveled fifteen hundred miles through the southern colonies with fellow Quaker Isaac Andrews to observe slavery firsthand and persuade Quakers to desist from slaveholding. He also decried poverty and championed Native American rights, visiting Native populations in Pennsylvania and New Jersey to learn from them and to share Quaker thought, most notably in the Wyoming Valley, Pennsylvania. Woolman died in England of smallpox at age fifty-two, having gone there to appeal to British Quakers to cease support for slavery. Throughout the eighteenth century, Quaker women also volunteered as missionaries in disproportionate numbers, often traveling in pairs as “Public Friends.”

After independence, most American missions focused domestically in an era of nation building. In 1808 Philadelphia merchant Robert Ralston (1761-1836) and other city leaders founded an organization, eventually called the Pennsylvania Bible Society, to provide religious literature to the public. The first of many such organizations nationwide, the society raised $7,000 to purchase stereotype printing plates from Britain and successfully lobbied Congress for a waiver of import tariffs. It printed over seventeen thousand Bibles from the original plates, the first use of that technology in the United States, and from its headquarters in Philadelphia has continued its efforts to provide religious literature to the public uninterrupted into the twenty-first century. In 1835 the Home Missionary Society of Philadelphia organized under Methodist-Episcopal auspices, becoming a nonsectarian agency ten years later, to serve the spiritual and material needs of the city’s poor. Society members made home visits to women, particularly widowed mothers, to provide food, coal, and funds. They established community houses to care for impoverished children and also placed them for foster care. Recognized in the city as a key early provider of social welfare services, the Home Missionary Society embraced professional welfare practices as they evolved and continued in successor organizations to minister to the needs of children into the twenty-first century.

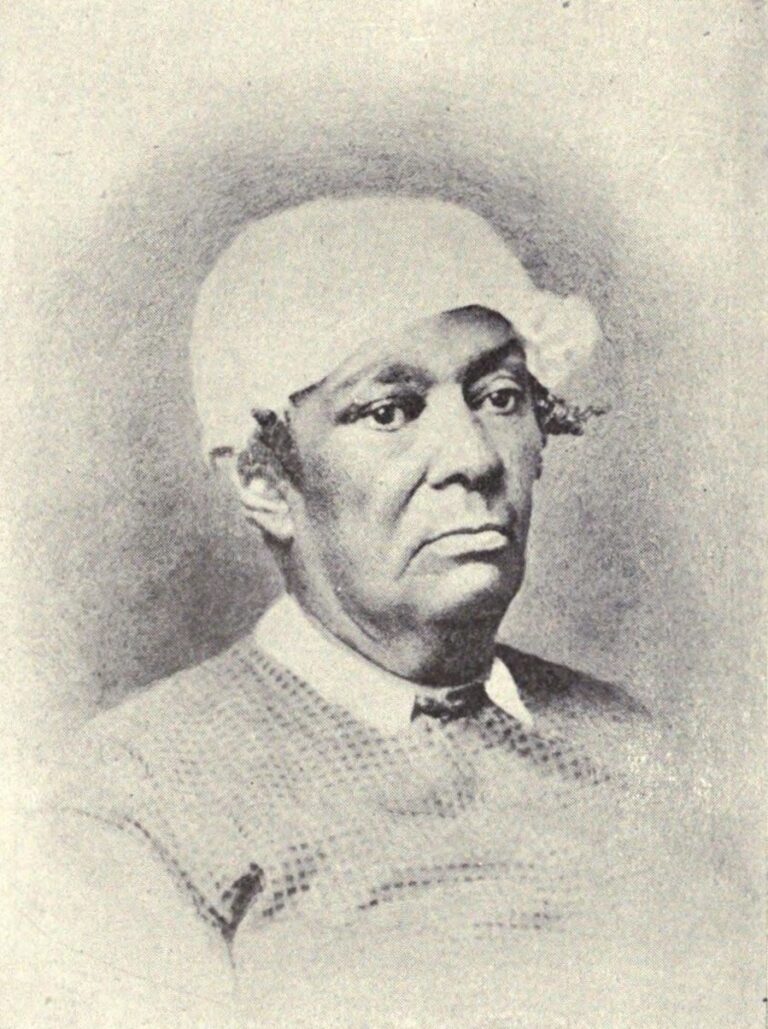

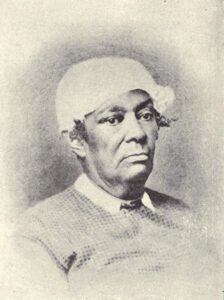

Domestic missions also included the rapid expansion of the African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded and headquartered in Philadelphia in 1816, as it sent clergy to establish AME churches across the northern and western United States, then to Canada and the Caribbean. The church grew most rapidly during and after the Civil War, when missionaries moved into southern states to minister to newly freed people. Dedicated AME evangelists established connections that helped spur southern black migration to Philadelphia in the early twentieth century. Meanwhile, among the first Philadelphians to serve as a missionary overseas was African American Presbyterian Betsey Stockton (c. 1798-1865). Born into slavery in Princeton, New Jersey, Stockton came as a child to work in the Philadelphia home of Presbyterian minister and future Princeton University president Ashbel Green. Religiously educated in the Green household, Stockton was later manumitted and applied to serve as a missionary in the Sandwich Islands. In 1822 she became the first single woman to serve as an American missionary overseas.

A Burst of Mission Work

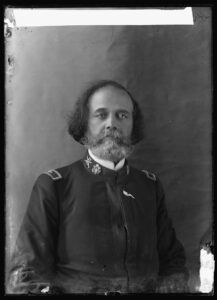

American missions work grew steadily through the nineteenth century, then soared after the 1890s in conjunction with the expansion of empire, increased ease of transoceanic travel, and the growth of a class of college-educated youth seeking meaningful life work. At home, several million members of Protestant missions societies sponsored field workers, published missions journals, and ran missions study programs for church members. Middle-class women played a significant role in the American missions movement at home and abroad, as missionary service gave single women a socially approved means to travel, while married women accompanied missionary husbands and found roles ministering to women and children, work often considered culturally inappropriate for male evangelists. Among such women was Fannie Jackson Coppin (1837-1913), who had been a newspaper columnist and principal of the Philadelphia Institute for Colored Youth before marrying African Methodist Episcopal minister Levi Jenkins Coppin (1848- 1924) in 1881. In 1902 the Coppinses moved for a decade to South Africa, there founding a missions school they named the Bethel Institute.

Burgeoning Chinese and Indian nationalist movements after World War I prompted Asian resistance to claims that Christianity was the one true faith, critiques that influenced some missionaries to reassess their goals and relationship to local cultures. Those at home took note. In the early 1930s Baptist layman and financier John D. Rockefeller Jr. (1874-1960), assembled a committee of well-heeled Protestants to travel to Asia as the Laymen’s Commission on Foreign Missions. Their goal was to study the state of the enterprise and issue a report recommending its future direction. Haverford College philosophy professor and Quaker mystic Rufus Jones (1863-1948) was the best-known of those on the commission. In 1926 Jones toured missions fields in Asia and in 1928 authored a paper for a missionary conference at Jerusalem, urging Christians to embrace the best in other religious traditions. That view was echoed in the Laymen’s Committee 1932 report, Re-Thinking Missions, which advanced a pluralist vision of religious accommodation and recommended that missionaries deemphasize Jesus and overt Christian symbolism in their appeals. Together with Harvard University philosopher William Ernest Hocking (1873-1966), Jones authored the report’s key chapters.

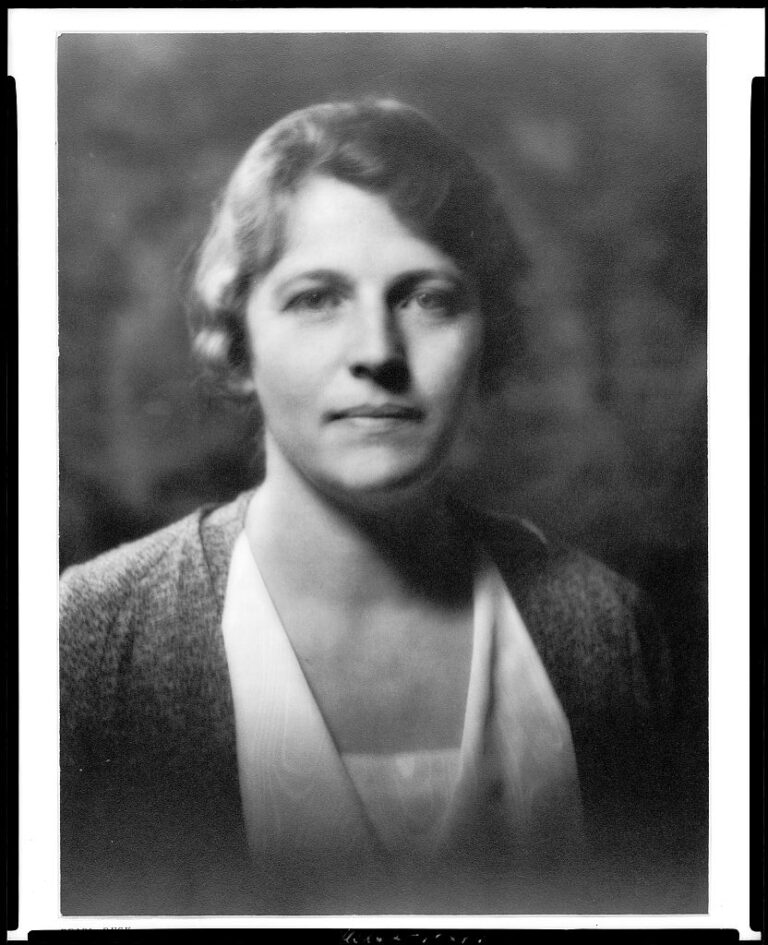

Pearl Buck’s Large Role

Re-Thinking Missions roiled American Protestantism, accelerating growing theological divisions. Its institutional impact was most prominent on the northern Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions. Writer Pearl Buck (1892-1973), the American daughter and wife of Presbyterian missionaries in China, publicly praised the Re-Thinking Missions as “the only book I have ever read which seems to me literally true in its every observation and right in its every conclusion.” A fierce intellectual who was ambivalent about the role of Christian missionaries in her beloved China, Buck was growing in fame as a novelist (she won the Pulitzer Prize in 1932 for The Good Earth), and her endorsement of the report garnered international attention. It outraged fundamentalist Presbyterian professor J. Gresham Machen (1881-1937), who in 1929 had left Princeton Theological Seminary to found the conservative Westminster Theological Seminary in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Machen called on the Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions to censure Buck and withdraw financial support for her and her husband. Instead, Buck resigned as a missionary, but Machen was sufficiently troubled by the board’s failure to censure her that he founded the Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions at Plymouth Meeting in 1933. Suspended by his presbytery in 1935 for his separatist actions, Machen and fellow fundamentalists next established what would become the Orthodox Presbyterian Church, headquartered in Willow Grove, to counter the liberalizing tendencies of the Presbyterian Church USA.

Philadelphia has remained home to several missions initiatives, the largest of which is the American Baptist International Missions, housed at American Baptist national headquarters at Valley Forge since 1962. The relatively small Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions has remained in Plymouth Meeting, while the newer Center for Student Missions in Germantown placed students on short-term urban service missions around the United States. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (Mormons), arguably the most prominent missional church in the United States, with active missions around the globe, in summer 2016 completed construction of a temple and education center near Logan Circle in Center City. The first Mormon temple in Pennsylvania, it was planned as the center for LDS worship and activity in the region.

Since the early twentieth century, missions activity in many Christian churches has emphasized medical, educational, and economic development assistance to others in Christ’s name in place of, or in addition to, explicit evangelism with the goal of conversion. In keeping with that trend, churches throughout the Philadelphia region have sponsored local, national, and international missions initiatives, working with community institutions that aid the poor in Philadelphia, Chester, Camden, and elsewhere in the region and sending members to provide disaster relief, build infrastructure, teach Vacation Bible School, and form relationships with Christians worldwide.

Gretchen E. Boger is Dean of Teaching & Learning and Director of the Merck Center for Teaching at St. George’s School in Middletown, Rhode Island. She earned her Ph.D in history from Princeton University in 2008 with a dissertation entitled “American Protestantism in the Asian Crucible, 1919-1939,” about the changing nature of missions after World War I and the role of returned missionaries in American religious discourse. (Author information current at date of publication.)

Copyright 2023, Rutgers University.