Philadelphia Fire

Essay

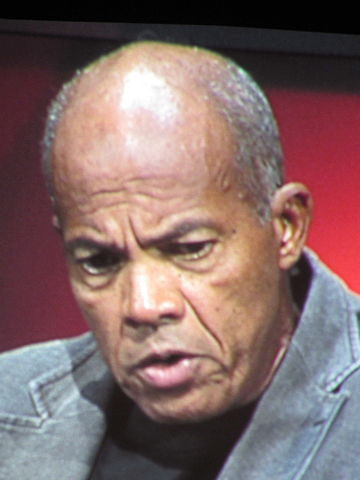

The seventh novel by African American writer John Edgar Wideman (b. 1941), Philadelphia Fire is a complex fictional account of the MOVE bombing, the 1985 tragedy in which Philadelphia police used explosives to dislodge the Afrocentric, back-to-nature group MOVE from its West Philadelphia compound. The violent assault resulted in the loss of eleven lives, including five children, and the burning of an African American neighborhood. Wideman’s novel, published in 1990, examines questions of black social agency and organization-building and describes, in sensuous prose, the condition of Philadelphia during the 1980s. The novel depicts this period, especially the mayoralty of Wilson Goode (b. 1938), the city’s first black mayor, as one of urban decay, police brutality, violent crime, and renewal initiatives that tended to worsen the condition of poor, black Philadelphians while revitalizing the city center.

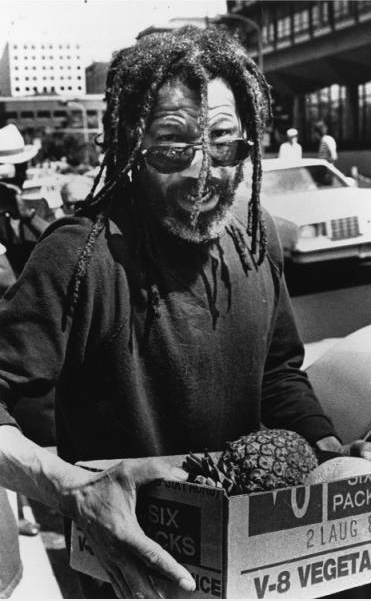

Philadelphia Fire begins with a black expatriate writer named Cudjoe, who returns to Philadelphia from Europe to search for the sole survivor of the bombing, an almost mythical, naked black boy seen escaping the flames and who has since disappeared. Cudjoe’s obsessive search for the boy, whom he never locates, results in a stirring portrait of the bombed group’s leader—called “King” in the novel, based on MOVE founder John Africa (Vincent Leaphart, 1931-85)—and an insider’s view of Philadelphia politics. In the novel’s semiautobiographical second part, John Edgar Wideman appears as a character. He learns about the MOVE bombing from television, writes and works as a university professor, and grapples with the fate of an incarcerated, mentally ill son. The final part of the novel follows a college-educated, homeless black man, J.B. While scraping by in the streets, J.B. witnesses the suicide of a white Philadelphian who appears to have in his possession the sacred book written by “King.” The novel ends with Cudjoe’s presence in Old City at a sparsely attended memorial for the bombing victims and with the threat of renewed racial strife.

Published in the year when Philadelphia’s homicide rate hit an all-time high, Philadelphia Fire exposed a city struggling with crime and blight, the consequence of more than two decades of white flight, a declining tax base, and the definitive collapse of the city’s industrial economy. The novel offered a critical portrait of the administration of Wilson Goode, the Southern-born black mayor then still in office, who had greenlighted the assault on the MOVE row house. Wideman pictures the Goode mayoralty (1984-92) as enabling a black elite to prosper while business-friendly renewal projects further displaced poor, black Philadelphians to the impoverished margins. The lost black boy of the fire whom Cudjoe searches for recalls the sole child survivor of the MOVE bombing, 13-year-old Birdie Africa, later known as Michael Moses Ward (1971-2013). Some critics have seen the white Philadelphian who commits suicide in part three as inspired by Donald Glassey (b. c.1946), the social worker who helped the semiliterate John Africa collate his views into a document known as The Guidelines (referred to as the “Book of Life” in Fire) and who helped propagate his views.

In addition to representing historical figures, Philadelphia Fire lavishes the urban surface of Philadelphia with beautiful prose. The novel includes an ode to Clark Park, where much of the novel’s action takes place; an exposition on pick-up basketball tournaments in the city; and lyrical treatment of the swelter of Philadelphia summers. In writing the novel, Wideman drew upon firsthand knowledge of the city. A native of Pittsburgh, Wideman studied as an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania, where he later served on the faculty from 1967 to 1973.

Philadelphia Fire, which netted Wideman his second PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction, has been seen as a literary record of potent racial and class divisions in Philadelphia; as a response to the apocalyptic warning for urban America found in James Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time (1963); and as a novel of despair and anger in the wake of unfulfilled promises of the civil rights era. But some critics have also found in the novel’s postmodern literary aesthetic a recipe for racial progress and understanding. Wide-ranging interpretations have associated the novel’s plurality of voices and viewpoints with radical democracy, recovery from traumatic experience, and even Wideman’s reclaiming of his African heritage. Critics have agreed, however, on the novel’s significance in exploring the anguished racial meaning and aftermath of the MOVE bombing, a low-water mark in Philadelphia’s checkered history of race relations.

J. Bret Maney is Assistant Professor of English at the City University of New York. He lived in West Philadelphia, not far from the site of the MOVE bombing, while completing his Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania.

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University