Poconos (The)

Essay

During the nineteenth century and especially through the twentieth century, “the Poconos” emerged as a premier vacation and recreation destination for Philadelphia-area residents. In doing so, it competed with the Jersey Shore and other places, using the appeals of nature, mountain air, recreational amenities, and especially improved access to attract visitors. As such, it became an extension of the Philadelphia region.

In describing “the Poconos,” a distinction is necessary between the Pocono Mountains and the Pocono region of northeastern Pennsylvania. The Pocono Mountains are part of the Allegheny Plateau, which at their highest point are some 2,100 feet high. The mountains are found in parts of Monroe, Pike, Wayne, Carbon, Lackawanna, and Luzerne Counties. By contrast, the Pocono region or “Poconos” has no official boundaries, apart from the Delaware River, which separates the Poconos from New Jersey to the east and from New York State to the northeast. According to the local vacation bureau, the Pocono region consists of Monroe, Pike, Carbon, and Wayne Counties. Other observers have expanded the boundaries of the Pocono region to include all of northeastern Pennsylvania. Whatever the boundaries, outsiders have seen and described the Poconos as vacationland.

In the eighteenth century, the Poconos were the land of the Lenni Lenape Indians, also called the Delaware people, who lived in the Lower Hudson Valley, New Jersey, eastern Pennsylvania and eastern Delaware. After the American Revolution, the Lenni Lenape moved west, and their descendants live mostly in Oklahoma, Wisconsin, and Canada.

The first Europeans in the Poconos were the Dutch who came from Kingston, New York, before 1710. Settlers of other ethnicities followed, yet by 1752 fewer than six thousand Europeans lived in northeastern Pennsylvania. The Indian exodus attracted more settlers. Some came from the Lehigh Valley into an area roughly equivalent to Monroe and Pike Counties. Others originated from Connecticut and settled in Wayne County.

Rocky Landscape

Settlers wanted to farm, but they discovered that the natural crop of the Pocono region was stones, which kept on rising from the mountainous soil every spring. Nature, though, was not totally unforgiving. The bark of the hemlock tree contained tannic acid, used to tan cattle hides. More important were the many and varied trees themselves. Throughout northeastern Pennsylvania, trees were cut, lashed into rafts, and floated down the Delaware River to Trenton, Philadelphia, and beyond. Unfortunately, nature’s bounty was limited. These extractive industries peaked in the 1850s, although they lingered until century’s end.

The future of the Poconos, mountainous and cool, was in vacationing, for which the region was well situated. New York City lay fewer than ninety miles to the east. About hundred miles to the south lay Philadelphia. However, reaching the Poconos in the horse-and-buggy age was challenging. A stagecoach trip from Philadelphia required three days of bumpy riding over unpaved roads. Hardy souls did make the trek, some to fish and hunt, others to see a pristine nature, especially the Delaware Water Gap, where the Delaware River cuts through the Kittatinny Mountains, leaving Mount Minsi on the Pennsylvania side and Mount Tammany on the New Jersey side.

The vacation age truly began with the coming of the railroad. In 1848 the Erie Railroad, which connected New York City to Lake Erie, opened a station at Port Jervis, New York–less than ten miles from Milford, the county seat of Pike County. Milford, on a slope above the Delaware River, soon attracted journalists and artists, among others, looking for a wilderness experience and escape, if only for a time.

The Poconos needed a railroad that traversed the region. In the 1850s, the Delaware, Western, and Lackawanna Railroad, commonly called the Lackawanna, connected the coal fields of northeastern Pennsylvania to New York City. It built stations in Delaware Water Gap, East Stroudsburg, and six other points in Monroe County. In the 1860s, a ride from New York to Monroe County took five hours, and technological improvements shortened the trip to some two hours by 1914. Nonetheless, unlike Philadelphia, New York City was not closely identified with the Poconos; New Yorkers also vacationed in the nearby Catskill Mountains.

Philadelphians had no direct route to the Poconos, but starting in 1864, they took the Pennsylvania Railroad to the Manunka Chunk station in New Jersey and connected with the Lackawanna. As the closest mountains to the City of Brotherly Love, the Poconos soon became an extension of Philadelphia.

Middle-Class Vacationing Grows

Increasing prosperity after the Civil War allowed more Americans to vacation. From Milford to the Delaware Water Gap, a distance of more than thirty miles, hotels and boarding houses opened near the Pennsylvania side (going downstream, the right bank) of the Delaware River. Summer camps introduced the region to children and their families. While the very rich vacationed in Newport, Rhode Island, and other fashionable resorts, the Poconos attracted the New York and Philadelphia middle class.

This vacation economy had a trickle effect. Some farmers saw extra money in hosting rooms to city folk and supplied resorts with food. Other farmers became full-time hoteliers. Outsiders came in and opened resorts. Tradesmen supplied goods and services; local residents had summer jobs.

In the resort world of the late nineteenth century, the once sleepy village of Delaware Water Gap in Monroe County stood out. The Delaware River allowed boating, fishing, and swimming. Mount Minsi, at one thousand feet not too rugged, lured hikers. The sedate could enjoy carriage rides or simply read. Victorian vacationers did not expect to be constantly on the move. The village was small and compact, an asset in the horse-and-buggy age, for vacationers did not stray far from the railroad. By 1900, some fifty resorts and boarding houses operated in and around Delaware Water Gap.

A scant fifteen miles from Delaware Water Gap lay Mount Pocono, near the middle of Monroe County, a former lumber center reborn as a resort town. Mount Pocono had two assets, a Lackawanna railroad station and an elevation of nearly two thousand feet, whereas the Gap’s elevation was only four hundred feet. Mount Pocono was cooler in the summer, a selling point before air conditioning. One resort advertised “Great Sleeping,” a big attraction for anyone who had endured a Philadelphia summer.

The automobile forever changed vacationing in the twentieth century and reshaped tourism in the Poconos. The first resort association in Monroe County emerged soon after 1900 with the coming of the automobile. Although the association advertised in Philadelphia and New York City newspapers, many resorts whose key asset had been a nearby train station suffered. The fate of two major resorts in the Gap was telling. The Water Gap House burned down in 1915; the Kittatinny in 1931. Neither was rebuilt.

Stroudsburg Secures Top Status

By the 1920s, Stroudsburg, located several miles from the Delaware River, had clearly become the chief town of the Poconos. The seat for Monroe County, Stroudsburg overshadowed Milford and Honesdale, the seat for Wayne County. Stroudsburg’s Victorian houses and banks attested to resort money. Nearby East Stroudsburg State Teachers College (renamed East Stroudsburg University in 1983) gave it the flavor of a college town.

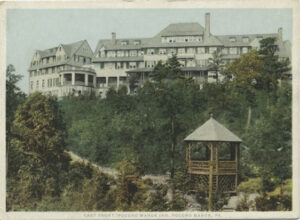

In the Roaring Twenties, the tony resorts were inland. Pocono Manor and the Inn at Buck Hill Falls were higher in the plateau, less than twenty miles from Stroudsburg but still in Monroe County. Built by well-off Philadelphia Quakers in the early 1900s, the two resorts had a unique ethos. Non-Quaker guests had to accept the Quaker lifestyle and avoid conspicuous consumption. Along with expected amenities such as a golf course, the Inn at Buck Hill Falls offered a touch of class: speakers on current issues and classical music. Some non-Quaker guests felt the two resorts were somewhat stuffy, especially since the teetotaler Quakers frowned on alcohol. In 1929, Skytop Lodge opened several miles from the Inn at Buck Hill Falls. Selective in its clientele, Skytop was soon considered the grandest of the Pocono resorts.

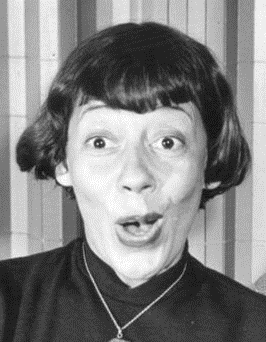

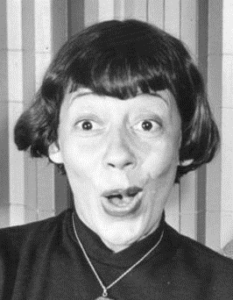

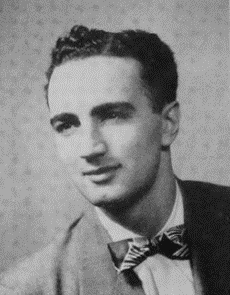

The Great Depression of the 1930s ended the good times. Many resorts closed. Some resorts tried to survive by being unique. Several catered to singles, one became a health farm, still another, a dude ranch. The Quaker resorts and Skytop Lodge kept enough of their old business by maintaining standards. Lower on the social scale was Unity House, located in Bushkill, Pike County. Opened in the early 1920s by the International Ladies’ Garment Workers Union, its selling point was below-cost vacations for working class, mostly Jewish union members. Young, middle-class Jews bypassed it for Camp Tamiment next door, which had a touch of the avant garde. Every weekend, its entertainment director, Max Liebman (1902-81), offered a fresh show of satire and revues, a formula that attracted ambitious, then-unknown comics such as Danny Kaye (1911-87) and Imogene Coca (1908-2001). In 1950, Liebman brought his routines to television in The Show of Shows, the Saturday Night Live of its era.

Although Unity House and Camp Tamiment were not alone in having a Jewish flavor, some Pocono resorts openly refused Jewish guests. Unlike New York’s Catskill Mountains, the Poconos were not seen as a Jewish playground.

The Pocono vacation industry has had a knack for renewal. After World War II, several entrepreneurs realized that many young newlyweds were uncomfortable honeymooning in family resorts, surrounded by people twice, even thrice, their ages. As a result, the Pocono region pioneered honeymoon hotels, which evolved into couples resorts. The heart-shaped bathtub, credited to Morris Wilkins (1925-2015), became a defining feature. The Poconos had become “the land of love.”

Skiing Keeps Its Hold

The fortunes of the honeymoon and couples resorts waned with changing tastes. But one postwar novelty, skiing, continued to thrive. The region’s irregular snowfall had bedeviled earlier skiing ventures, but by the early 1960s new technology easily converted water into snow. The Bensinger brothers, who were Stroudsburg attorneys, together with Philadelphia investors, opened the Camelback ski area in 1963. Its success led to the launching of other ski areas. By 1984, according to the Pocono Mountain Vacation Bureau, skiing accounted for a quarter of the region’s tourist income. Another addition to the vacation mix was the Pocono Raceway in Long Pond. Opened in 1971 by Joseph Mattioli (1925-2012), a Philadelphia dentist whose second career was the speedway, Pocono Raceway has hosted NASCAR, Indy car, and other speed races over the years.

After World War II, the Poconos vacation zone grew. In 1948, the Pocono Mountains Vacation Bureau expanded to include Carbon County, including the scenic village of Jim Thorpe, which, with its narrow, crooked streets and stone buildings, provided an Alpine look. New highways made the Poconos more accessible. In the first half of the twentieth century, Philadelphians had to endure the traffic lights and stop signs of Pennsylvania Route 611 to reach the Poconos. In 1957, the completion of the Northeast Extension of the Pennsylvania Turnpike reduced travel time. Likewise, travel time from New York City and New Jersey was lessened when Interstate 80 was completed in 1973. Interstate 84 serves Pike County.

The new roads brought dramatic population growth to Monroe, Pike, and Wayne Counties. Pike’s population grew sevenfold between 1950 and 2010, to more than 57,000 residents. Monroe’s 2010 population of 170,000 represented a fivefold increase from 1950. In the same period, Wayne County’s population nearly doubled. The high cost of living in New Jersey and New York helped to fuel the population boom. Many residents of these high-tax states fled to the relatively low taxes and affordable housing in the Poconos. The Poconos also became an attractive retirement place for people from the Philadelphia region and elsewhere.

A Limited Economy

The region’s economy did not grow to accommodate the larger population. Apart from the vacation and recreation industry, in the early twenty-first century, the only big employers were East Stroudsburg University, Sanofi Pasteur (pharmaceuticals), Tobyhanna Army Depot, and the hospitals. Many residents of the Poconos took Pennsylvania Route 33 to jobs in the Lehigh Valley; others commuted to New Jersey and New York City via Interstate 80.

The demographics of the region also changed. Unlike much of northeastern Pennsylvania, which had drawn eastern and southern Europeans to work in coal mines, the population of the Poconos remained overwhelmingly northern European, and the economy stayed rural. Monroe County had changed the most. Although 70 percent of its population was white in 2010, 29 percent of the white population was of southern and eastern European extraction. Hispanics and African Americans made up 26 percent of the total population. Also, Asians and Middle Easterners were becoming part of the population mix. Politics reflected this demographic change. Once solidly Republican, Monroe County voted for Democrats Barack Obama (b. 1961) in 2008 and 2012 and for Hillary Clinton (b. 1947) in 2016.

The vacation business also changed. Just as automobiles caused a reorientation after 1900, jet travel impacted the Poconos in the second half of the twentieth century. In the time it took a Philadelphian or New Yorker to drive to the Poconos, that person could fly to Bermuda or Florida. In the age of widely available air conditioning, city folks no longer needed the Poconos to escape the muggy summers of Philadelphia and New York. Many of the Pocono resorts that had survived the Great Depression collapsed, including the Inn at Buck Hill Falls, Unity House, and Camp Tamiment.

Nature as always remained a draw, but going into the twenty-first century, the region’s capacity for renewal was best expressed by year-round resorts. Their expansive indoor facilities, especially water parks, allowed the Poconos to compete with Florida in the winter. Kalahari water park (by Interstate 380) boasted of being the largest in the United States. As always, the region’s visitor bureau vigorously promoted the amenities and accessibility of the Poconos, especially in the Philadelphia market.

Lawrence Squeri is Professor Emeritus of History at East Stroudsburg University. He is the author of Better in the Poconos: The Story of Pennsylvania’s Vacationland (Pennsylvania State University Press, 2002) and Waiting for Contact: The Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (University Press of Florida, 2016.) (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.