Polish Settlement and Poland

Essay

A few aristocratic Polish emigres—the Revolutionary War hero Thaddeus Kosciusko (1746-1817), for example—found their way to Philadelphia in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Large-scale Polish immigration to the Philadelphia region, however, began only after the Civil War, reaching its climax in the years immediately preceding World War I. Between 1870 and 1920, at least 700,000 Poles came to work in Pennsylvania’s heavy industries, primarily coal mining, iron and steel. A migration comprised primarily of young men in search of work, the initial intention was to return home with American earnings. The availability of better work opportunities and the outbreak of World War I reduced the return migration and led to the formation of at least fourteen permanent Polish settlements across the Philadelphia region. Although dispersed, these communities established lasting social institutions capable of maintaining their identity and culture.

The millions of Poles who journeyed to America (both North and South) before World War I were leaving a country that no longer existed. Coveting its rich farmland and strategic location, Russia, Prussia, and Austria-Hungary repeatedly partitioned Poland in the eighteenth century, with Russia taking the largest portion. The subsequent abolition of serfdom in Austria-Hungary (1840s) and Russia (1860s), followed by land reforms, allowed former serfs to move and to buy land. As the population exploded, succeeding generations divided land holdings, creating a large population of underemployed male farmers who sought unskilled work on farms or in factories and mines outside of Poland, particularly in France, Germany, Belgium, and North Africa before migrating to North and South America. In Germany between 1870 and 1891, the Kulturkampf, a formalized attack on Catholicism and its Polish believers by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1815-98), instigated early Polish emigration from that country with many finding their way to the Philadelphia region.

Although few in number when compared with their Galician (Austrian) and Russian counterparts, German Poles were generally literate, tended to stay permanently, and often came as families. Their presence established the initial connections and organizations that benefited those who followed. Because Poles from Galicia and Russia comprised 85-90 percent of the total migration, the large majority of Polish immigrants were young peasant men of prime working age (17-39). Mostly unmarried, they arrived with the intention, much like Italian migrants of the time, of returning home with American earnings to increase or improve their land holdings. At least 40-45 percent actually returned to Europe, and more would have done so if not for the outbreak of World War I and the decision to remain in America rather than be drafted into the Russian and Hapsburg armies.

The Demand for Unskilled Labor

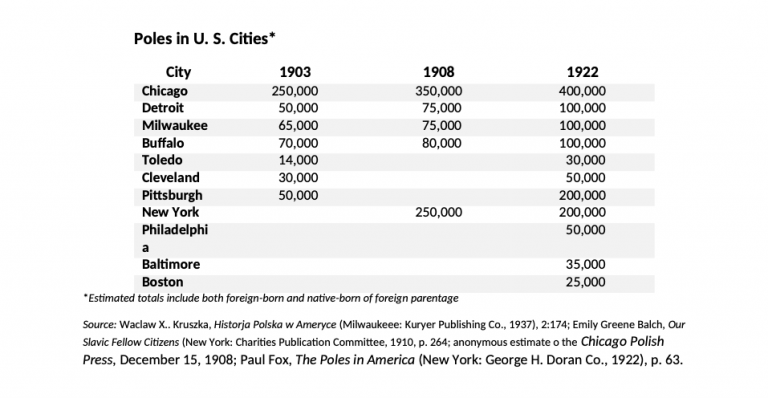

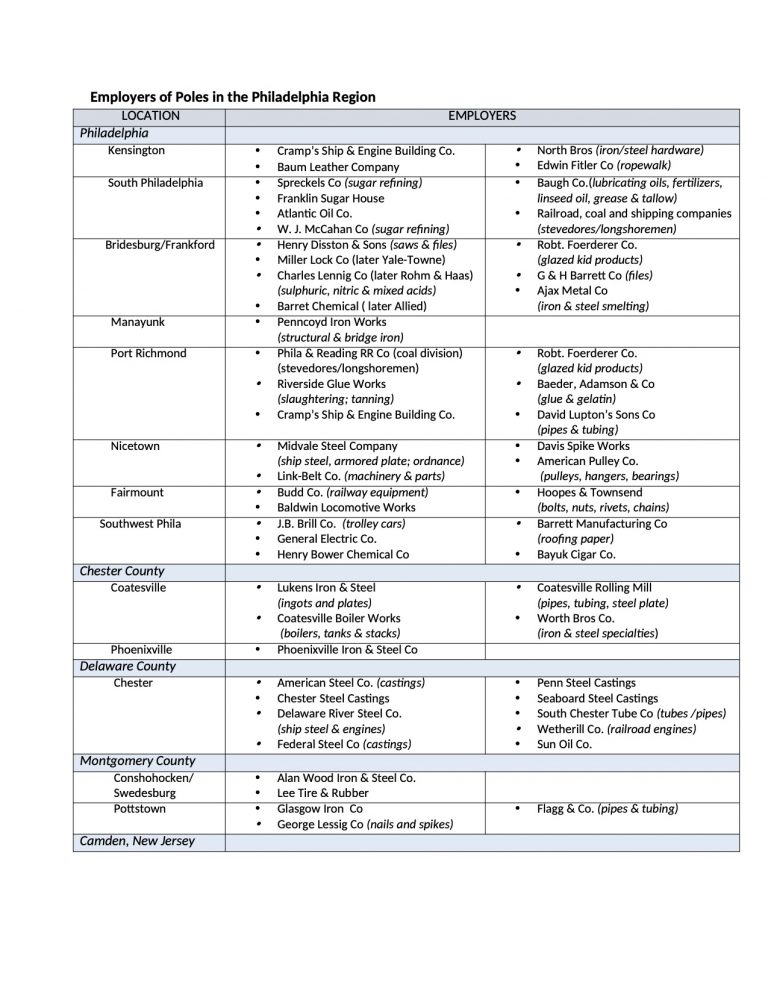

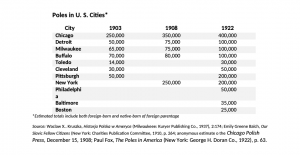

The Polish influx to Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia region began in the 1870s and accelerated after 1900. Poles remained the largest group (337,000) coming to Pennsylvania until 1901 when southern Italians and Sicilians pushed them into second place. An additional 340,000 Poles arrived between 1899 and 1914. Approximately 85-90 percent of the Polish population settled in the anthracite regions (primarily Northumberland and Luzerne Counties) and the Pittsburgh area (Allegheny County), with the remainder in the greater Philadelphia region. Poles were attracted to Pennsylvania by the availability of unskilled work in heavy industry. In some years, Poles and their native-born sons were the majority of those employed in the anthracite mines. By 1910, 65-75 percent of all Pennsylvania steel workers were foreign-born, with Poles and Slovaks the leading groups. Poles also dominated the state’s leather (tanning), meatpacking (slaughtering), oil, chemical and shipping (stevedores and longshoremen) industries, all of which had a significant presence in the greater Philadelphia region. The location of heavy industrial work eventually led to the establishment of at least fourteen settlements throughout the area. Because this work was volatile and not always permanent, these settlements were extremely transient places. In some years the turnover was more than half the population. Immigrants in search of work moved from one settlement to the other, back and forth to the coal regions, or to major Polish locations in Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and Chicago. The major move, however, was the return home.

Despite the extreme transiency, Polish immigrants formed strong, stable communities in the places where they found work. The increasing presence of women in the years 1907 to 1914, which led to marriage, children, and the need for institutions such as churches and schools, constrained mobility. In an economy of erratic male employment, the ability of women to find work as cleaning personnel or in paper, candy, or terra cotta factories, or to supplement household income by taking in lodgers and boarders or piecework, also reduced mobility. Property ownership, made possible by the affordability and ubiquity of the region’s row houses, further restrained geographic movement. Finally, an infrastructure of institutions and organizations enabled stable communities to form and remain intact, no matter how often the population changed. Polish workers could move from Nicetown or Port Richmond to Camden, Wilkes-Barre, or Chicago and find a Polish parish, school, newspaper, and fraternal or beneficial society that supported their needs. The Poles referred to this vast and comprehensive social network in America as Polonia. By 1914, an estimated 75 percent of Poles in the United States belonged to one or more of Polonia’s more than seven thousand societies.

As the first to arrive in the 1870s and 1880s, German Poles settled in German neighborhoods, such as the Northern Liberties, Kensington, South Philadelphia, Bridesburg, Coatesville, and South Camden, secured lodging through German contacts, and found employment in German-owned leather, textile, and chemical plants. They also established the first Polish parishes and organizations.

The Roman Catholic parish was the core of Polonia and its most formidable institution. In Poland, family and community life centered on the church. The priest was the recognized leader. Literate and often educated, he championed the peasants’ release from serfdom and fought against Prussian and Russian efforts to suppress the Polish language and Roman Catholic faith. Much more than a religious entity, the Polish parish organized not only weddings, funerals, baptisms, and liturgical processions but also dances, picnics, theatrical performances, sporting events, and lectures. Through pulpit, press, and school, it disseminated information to members and newcomers. A powerful social force invested with moral authority, its bonds were so strong that the parish name became synonymous with the territory in which it was located.

The Philadelphia Parishes

Initially, Poles in Philadelphia and Camden traveled to Trenton, Baltimore, or Shenandoah, Pennsylvania, to hear Mass and receive the sacraments in their own language, or they attended local Irish and German Catholic churches. Neither solution was satisfactory. Traveling long distances was unsustainable, and relying on “foreigners”—German and Irish—was untenable. Relations between Poles and Germans were often tense, a carryover of Bismarck’s Kulturkampf, and newer arrivals from Russia and Galicia did not speak German. At home, Poles were used to choosing their priests and overseeing parish finances, but in America the Irish hierarchy had total control of appointments and finances. And lack of Polish representation in the hierarchy was intolerable. Responding to the situation, in the 1890s Poles from Pennsylvania’s coal regions were instrumental in forming the Polish National Catholic Church, the only successful schismatic movement in American Catholicism. John Joseph Krol (1910-96), born in Buffalo, New York, became one of the first Polish-Americans to serve in the national Roman Catholic hierarchy and the first in the nation to be appointed archbishop when appointed to serve Philadelphia from 1961 to 1988. He was designated Cardinal in 1967.

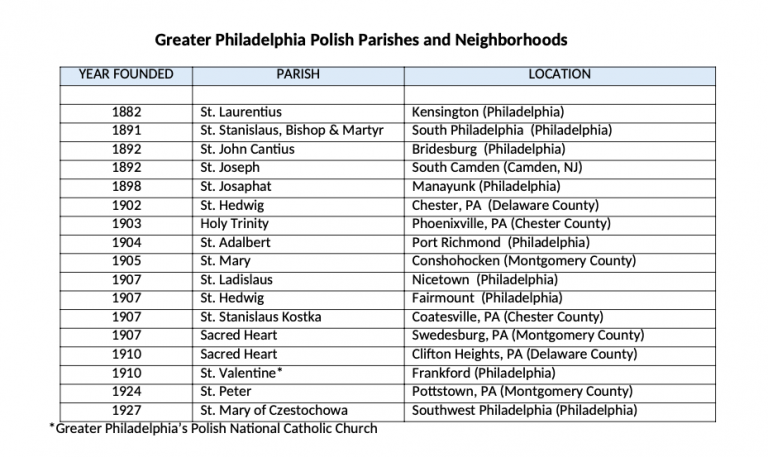

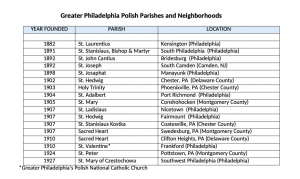

Between 1882 and 1927, Poles established seventeen parishes in the Philadelphia metropolitan region, sixteen Roman Catholic and one Polish National Catholic, all in neighborhoods with heavy industrial work that had prompted their settlement. On January 29, 1882, Poles from Camden, Chester, Wilmington, and Philadelphia met at Muellershen Hall (347 N. Third Street, in the Northern Liberties section of Philadelphia) to plan the first local parish. Forty-seven families took up a collection to construct or purchase a church building. Local Protestants blocked the attempt on four occasions. Resorting to a ruse, Polish priests and leaders passed themselves off as German businessmen and purchased land at the corner of Vienna (later Berks) and Memphis Streets in Kensington. They constructed a large “basement” and used it as a church until completion of the upper church level in 1890. With members of the local hierarchy in attendance, the Poles dedicated the first Polish church in the region to St. Laurentius on September 21, 1890.

In time, St. Adalbert, founded in 1904 with six hundred souls from Galicia and Russian Poland, became the area’s largest Polish parish and confirmed Port Richmond as the mother colony of the Polish population in the Delaware Valley. The parish built a grand church at Allegheny and Thompson Streets with money collected during the Panic of 1907. All parishes included a school staffed by one of the Polish sisterhoods–Sisters of the Holy Family of Nazareth, Felician Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis, and the Bernadine Sisters of the Third Order of St. Francis. The Holy Family Sisters also founded Nazareth Academy, a private elementary and secondary school for girls; Holy Family College (later University); and Nazareth Hospital, all located in Northeast Philadelphia. The Felician Sisters founded and staffed St. Joseph’s Hospital, at Sixteenth Street and Girard Avenue.

Fraternal-Beneficial Societies

Once in place, the Polish parish gave rise to other institutions, the most important of which was the fraternal-beneficial society. More popular with Poles and other Slavs than with other immigrants, the fraternal-beneficial was basically a collectively financed insurance association through which the Polish immigrant could purchase an insurance policy for a nickel or dime a week. In time, the larger beneficials used their funds to provide mortgages and business and educational loans as well as offering a range of social and recreational activities

The largest beneficial societies active in the Philadelphia region were branches of organizations founded in Chicago: the Polish Roman Catholic Union (PRCU); its secular counterpart, the Polish National Alliance (PNA); and the Polish Women’s Alliance (PWA). Taking as its motto “God and Country,” the Polish Roman Catholic Union worked to prevent the absorption of Poles into the Irish-dominated Catholic Church. By 1925 it had 188,000 members nationwide and kept them informed through its newspaper, Narod Polski (Polish Nation). By the 1970s, it had eight chapters in the Philadelphia region. The larger Polish National Alliance reversed the PRCU’s motto to “Country and God” to assure outsiders of Polish-American loyalty to the United States and published Zgoda (Harmony), a daily newspaper. By 1925 it had 220,000 members nationwide and had established Alliance College in Cambridge Springs, Pennsylvania, to educate the children of Polonia. By the 1970s PNA District VI had seventy-four lodges in Delaware, southern New Jersey, southeastern Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. The Polish Women’s Alliance grew nationally to twenty-five thousand members by 1925, and its house organ Glos Polek (Voice of the People) focused on women’s issues. By the 1970s, the PWA had six chapters in the Philadelphia area.

Philadelphia parish neighborhoods produced two beneficial societies that later expanded throughout Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware, and Maryland. The Polish Beneficial Society of St. John Cantius, originating in Bridesburg in 1899 (later known simply as the Polish Beneficial Society or PBS) offered low-interest mortgages and loans, supported charitable and civic causes, and sponsored lectures, dance classes, and its own newspaper. Ahead of its time, it accepted women as members and leaders as early as 1902. Unja Polek w Ameryce (Union of Polish Women in America or UPWA), founded in 1920, grew out of the Port Richmond chapter of the Bialy Krzyz or White Cross, an organization of Polish women that provided sweaters, blankets, long johns, and bandages for Polish and Polish American soldiers during World War I. Originally incorporated to sell insurance to women and children of Slavic descent in Pennsylvania, the group later extended its operations to New Jersey and Delaware. Unja Polek provided mortgages and college scholarships and sponsored dance groups, a glee club, girls youth group (the “Debs”), and hosted the annual Debutante Ball for the area’s Polonia. By 1980 UPWA had nearly $5 million of insurance in force and assets of $2.5 million. Other neighborhood financial groups that became regional institutions were Nicetown’s Kazimierz Wielki (Casimir the Great) Savings and Loan Association (later a division of Washington Savings Association), founded in 1898, and Port Richmond’s Polonia Federal Savings and Loan Association (later Polonia Bank), founded in 1923.

Polish-Language Newspapers

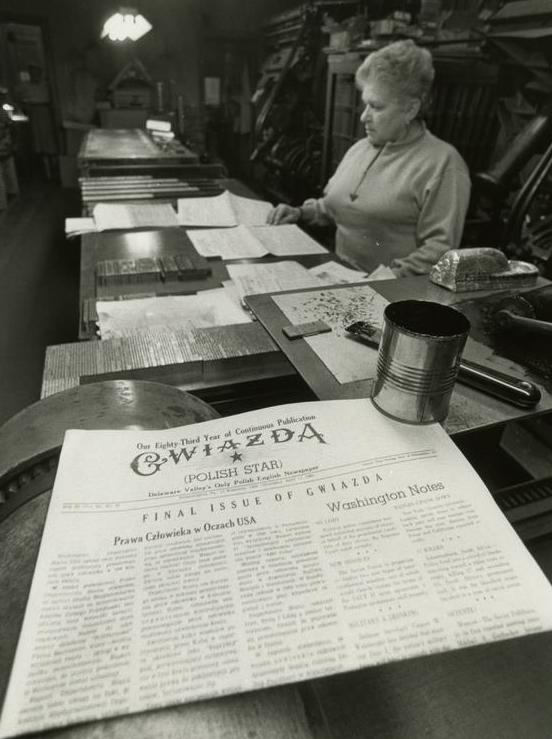

In addition to national Polish-language publications that kept readers informed of events in Poland and America, local Polonia supported several independent Polish language newspapers: Gwiazda (Star), Przyjaciel Ludu (Friend of the People), Jednosc (Unity), and Patryota (Patriot). Gwiazda became the official voice of Unja Polek; it was the last of the Philadelphia area Polish-language papers to cease publication (1984). The Polish American Journal, founded in 1911 in Scranton, Pennsylvania, and later published in New York, offered “news for Polish Americans in English.”

Polish neighborhoods also supported fraternal societies focused on special interests (sports, literature, music) and experiences (military service). Most had their own buildings or designated spaces. Port Richmond supported the Fraternal Association of Joseph Pilsudski, the city’s largest such organization; the Polish Eagle Sports Club (which sponsored a team affiliated with the United States Soccer League of Pennsylvania); and the Polish American String Band, a participant in the city’s annual Mummers Parade. Manayunk housed the Polonia Hall Association and the city’s most active Sokol or Falcon’s Nest (#171), a branch of the national Polish Falcons of America, a group that supported gym classes and athletic programs. Neighborhood veterans groups included chapters representing the Polish army, air force and underground forces, as well as Polish-American veterans from World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. Other fraternals transcended neighborhood boundaries, attracting members from across the region: the Polish Police Association of Philadelphia; the Paderewski Choral Society; the Polish Dramatic Theater; the Polish Intercollegiate Club (Polskie Kolko Miedzykolegialne or PKM) for college students, sponsor of a Polish folk dance group; the Jagellonian Law Society (for lawyers); and the Polish Professional Society for physicians, lawyers, engineers, executives, and other Polish and Polish American professionals living in the Delaware Valley.

From the beginning, Poles were concerned with maintaining their identity and passing their language, history, and traditions to succeeding generations. Local initiatives took the form of theater groups, literary and poetry circles, libraries, and language schools. Frankford housed a Polish Library (4743 Melrose Street) prior to World War I, and Port Richmond established the Kosciusko Literary Association to promote a circulating library and the reading of Polish history and literature. By the 1940s szkolki doksznalcajace, or supplementary schools, appeared in many parishes, such as St. Adalbert and St. John Cantius, primarily to teach Polish language and history to new generations of Polish Americans. The Adam Mickiewicz Polish Language School, founded in 1922, was the largest and most successful. The Uniwersytet Ludowy, or Polish People’s University, an outgrowth of Poland’s socialist movement at the turn of the twentieth century, had a section in Philadelphia. It aimed to bring high forms of Polish culture “to the people” (especially uneducated, often illiterate, Polish immigrants) via lectures and discussions. Philadelphia Poles also formed a prominent chapter of the Kosciuszko Foundation, Polonia’s most prestigious and important cultural organization (founded in New York City in 1927), which promoted interest in Polish history, art, music and science through funded research, exhibits, concerts and lectures.

The Dom Polski

Wherever they settled in large numbers in the United States, Poles created a Dom Polski (Polish home), a house or physical space that serves as headquarters for multiple cultural and educational organizations. The Philadelphia region’s Dom Polski began in 1900 as the Polish Library Association of Philadelphia in Port Richmond. With the growth of the Polish population and proliferation of cultural organizations, the region’s Polish leadership purchased a larger building after World War II, at 9150 Academy Road in Northeast Philadelphia, and incorporated the site as the Associated Polish Home. Over time, the Associated Polish Home came to host the Uniwersytet Ludowy, the Adam Mickiewicz Polish Language School, the Marcella Kochanska Sembrich (famous Polish opera singer (1858-1935) Female Chorus (successor to the Paderewski Choral Society and a member of District 7 of the Polish Singers Alliance of America), the PKM-Polish Intercollegiate Club’s Polish Folk Dance and Music Ensemble, the Philadelphia chapter of the Kosciuszko Foundation, the Polish Heritage Society of Philadelphia, and the Adam Mularczyk Theater Company. It also provided rental and meeting spaces for weddings, other social events and conferences.

Cultural promotion and efforts to educate Americans about Polish culture and history intensified in the years following World War II, partially in response to nativism, discrimination, and negative stereotyping. In 1965 Philadelphia’s Polish Americans founded the Polish Heritage Society to offer concerts and lectures to the larger American audience in addition to Polish Americans. In 1981 regional leaders established the Polish American Cultural Center to “serve the varied social and cultural needs of Polish Americans and to promote public awareness and appreciation of Polish history and cultural heritage to as broad an audience as possible.” Originally housed in St. Hedwig’s (Jadwiga) Parish on North Twenty-Fourth Street in Philadelphia, the center moved in 1987 to 308 Walnut Street near Independence Hall, where it added a museum and exhibit hall.

Realizing that more than cultural education and outreach were necessary to promote their interests in America, Poles turned to political organization. As early as 1871 German Poles founded the Kosciuszko Club, the first formal Polish organization in the Philadelphia region, to serve as a clearinghouse for newly arrived Poles seeking jobs and lodgings and as a social center for the largely male group. The club’s success led to the purchase of a building at Front and Green Streets in the Northern Liberties. The club required each member to become a United States citizen as soon as possible, taking as its motto “A Good Pole is a Good American Citizen.” Upon obtaining citizenship, the new American received a substantial monetary gift. The group was short-lived, however, overwhelmed by too many Poles from Russia and Galicia seeking quick work with no intention of staying in the country.

Political Participation

Initially, the Poles’ political activity focused primarily on the reconstitution of the Polish state, a goal achieved at Versailles in 1918. Later, they sought to free Poland from communism and to work for greater Polish-American representation in government. The Pulaski Citizens Association of Philadelphia, for example, founded in 1937 as a successor to the Polish Political Club of Nicetown, encouraged political participation of Polish Americans and advanced Polish causes and candidates. After World War II Polish-American leaders formed the Polish American Citizens League of Pennsylvania to recruit, support, and elect Polish Americans to political office throughout the state.

Because of the proliferation of organizations—beneficial, fraternal, cultural, and political—pressure to form an umbrella organization was intense. During World War I Central Councils (Centrala Towarzystwo Polskich) formed in most cities, including Philadelphia, lobbied for an independent Poland and later coalesced to serve as the predecessor to the Polish American Congress. Founded in 1944 in Buffalo, New York, to fight communism and to lobby for a free Poland, the Polish American Congress became Polonia’s major political organization and lobbying group. By 2010 it was a federation of more than three thousand organizations with forty-one state divisions promoting Polish-American political power and social recognition and serving as a watchdog for Polish defamation and discrimination. More than four hundred representatives from 156 of the Philadelphia area’s Polish organizations and five Polish newspapers attended the founding meeting of the Eastern Pennsylvania District of the Polish American Congress in Port Richmond on February 25, 1945. The Eastern Division-PAC coordinated or sponsored major annual Polish events, such as Polish Heritage Month (February), Kosciusko Day Observance (also in February) at the General Thaddeus Kosciuszko House, the Pulaski Day parade (first week of October), and Polish Constitution Day (first week of May). Its efforts resulted in the designation of the Kosciuszko House, at Third and Pine Streets, as a national historical memorial and part of Independence National Historical Park.

By the late 1960s, the Philadelphia region’s increasingly educated, affluent Polish Americans had relocated to areas of Northeast Philadelphia and the Philadelphia and New Jersey suburbs. Their success, however, contrasted with less fortunate members of Polonia, many of them elderly, who often lived in the region’s original Polish neighborhoods, areas adversely affected by the decline of the industries that had supported them. To serve this population, Polish American leaders, led by a Philadelphia Polish pastor, formed Polish American Social Services (PASS) in 1972 to secure federal, state, and local funds for outreach and referral services such as fuel and tax rebates, food stamps, and pharmaceutical assistance for the elderly. The organization later coordinated with United Social Services to serve at least seven additional ethnic communities from its location at 308 Walnut Street, the site of the Polish American Cultural Center, Museum and Exhibit Hall. The Polish American Congress, Eastern Pennsylvania District; the Polish American Radio Program (WCBC 1490 AM); and the Polish American News also moved their headquarters to the site, affirming the building’s role as another version of the Dom Polski.

Post-World War II Invigoration

By the last quarter of the twentieth century, the Philadelphia region’s Polonia was at a crossroads. As the descendants of the great Polish migration of 1870-1920 increasingly dispersed, their original parishes and neighborhoods fell into decline or extinction, and their organizations consolidated, closed, or redefined themselves. Most often, advancing education, upward mobility into the middle classes, and accelerating assimilation fueled these changes. Polonia, however, was reinvigorated after World War II by the arrival of new Polish populations. Under the 1948 Displaced Persons Act, several thousand Poles and others displaced from Central and Eastern Europe settled in the region. The United States Refugee Act of 1980 allowed thousands of Poles, active in Solidarnosc (Solidarity), the movement to free Poland from Soviet Communism, to settle in the United States in the 1980s and 1990s. The “Solidarity Poles” who settled in the Philadelphia region were most often English-speaking educated professionals who revitalized and redirected a large segment of Polonia’s cultural life through active participation in the Associated Polish Home, a reinvigorated chapter of the Kosciuszko Foundation, and commitment to the National Shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa near Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

With the decline or demise of Polish parishes, the religious and cultural focus of the area’s Polonia increasingly centered on the National Shrine of Our Lady of Czestochowa in Bucks County. The Pennsylvania Shrine was constructed as a tribute to the Black Madonna, a revered icon housed since 1382 in Czestochowa, Poland, and regarded as the guardian of the Polish people. Pauline Fathers (Order of St. Paul the Hermit), custodians of the original shrine, were suppressed by the Communist government in 1950. Seeking to continue their apostolate to foster devotion to the Mother of God, they purchased farmland in Bucks County to be near the large population centers of the East Coast. A successful fund-raising appeal to Polish Americans in the United States and Canada led to the building and dedication of a large church or shrine in time for ceremonies in August 1966 to commemorate the 1000th anniversary of the coming of Christianity to Poland. The addition of a cemetery and hosting of festivals and exhibits to promote Polish traditions enhanced its religious and symbolic significance. By the early twenty-first century, the “American Czestochowa” had been visited by thousands of Polish Americans from across the country and Canada, bringing together in one place the descendants of those who came in the great migration of 1870-1920, those who came during and after World War II, and those who fled martial law in Poland after 1981.

Caroline Golab is a cultural geographer and historian specializing in urbanization and immigration. Her Immigrant Destinations (Temple University Press 1977) is a seminal work that demonstrates the correlation between immigrant populations and industrial work patterns within and across America’s cities in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. She is a former Commonwealth Lecturer specializing in Pennsylvania history and has served as a Commissioner (Designated City Historian) for the City of Philadelphia.

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University