Printmaking

Essay

Beginning in the mid-nineteenth century, Philadelphia became a leading center of printmaking in the United States. While publishing companies had operated in the city since the eighteenth century, the technological innovations of the firm of Peter S. Duval (1804/5-86) transformed Philadelphia’s lithographic trade into a booming industry. Duval’s commitment to improving printmaking methods and achieving complex artistic expression was taken up in the twentieth century by the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project. Then, following World War II, a flourishing of printmaking centers, including the Brandywine Workshop and the Brodsky Center for Innovative Editions, enabled a new generation of artists to experiment with a variety of techniques and materials, cementing the Philadelphia region’s reputation as a pioneer in the field of printmaking.

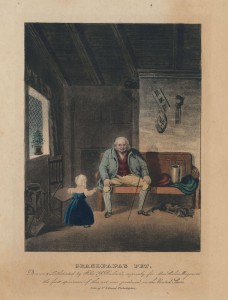

Philadelphia witnessed the birth of American lithography in 1819 when Bass Otis (1784-1861) produced the country’s first lithograph. Invented in Germany in 1798 by Alois Senefelder (1771-1834), lithography is a planographic process that relies on the inability of oil and water to mix. A greasy crayon is applied to a smooth limestone or metal plate, which is then treated with a chemical solution, sponged with water, inked, and sent through a printing press. As American artists and printers experimented with the technique in the 1820s, they discovered that it allowed for long print runs, large sizes, and the easy combination of text and image. Commercial lithographic production began in Philadelphia in 1828 with the founding of Kennedy & Lucas (active 1828-33). Within just a few years, the industry dramatically expanded. By 1878, over 500 artists, lithographers, printers, and publishers had participated in the city’s lithographic trade.

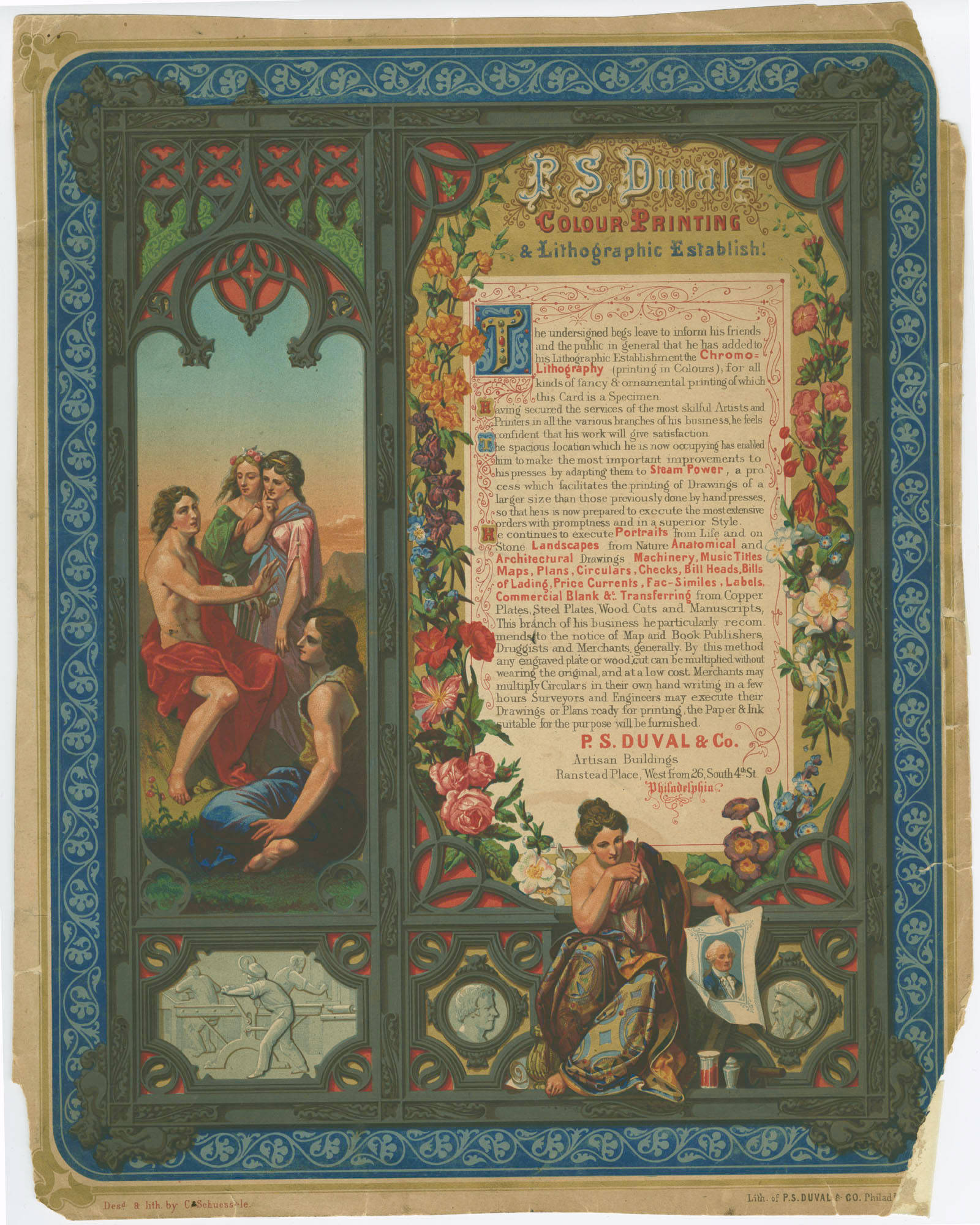

No publisher was more influential in transforming the art and the business of lithography than Peter Duval. The French lithographer arrived in Philadelphia in 1831 to work for the publisher Cephas G. Childs (1793-1871) Although only twenty-six years old, Duval brought a level of expertise that few Americans could match. In fact, he was the only lithographer in Philadelphia who had received professional training. After quickly achieving success with Childs, he partnered with George Lehman (ca. 1800-70) to found Lehman & Duval (Dock Street and Bank Alley) in 1834. Three years later, he opened his own firm, P.S. Duval’s Lithographic Establishment, at the same location. It then moved to the Artisans’ Building between Fourth and Fifth Streets, between Chestnut and Market Streets, from 1848 to 1857.

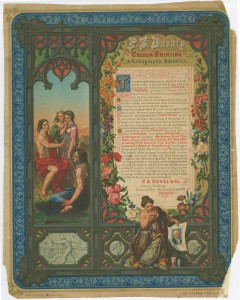

A Wide Range of Printing Services

In contrast to Philadelphia firms in the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries that specialized in one product, Duval offered a wide range of services, including advertisements, billheads, certificates, checks, circulars, labels, maps, pamphlets, sheet music covers, and title pages. His workshop also served as a training ground for a generation of printmakers, whose artistic abilities, he believed, should match those of fine artists. Through on-the-job instruction, lithographers not only developed their technical skills but also their drawing and painting skills. Because of Duval’s dedication to technological improvement, Philadelphia became one of the first cities in the United States to utilize steam power in lithographic printing. He successfully mechanized one step of the printing process—the pulling of the stone through the press—in 1850 in an attempt to save muscle power and increase efficiency. By the 1860s, he managed to automate the rest of the procedure, including the dampening and inking of the stone.

In addition to streamlining lithographic practices, Duval was a forerunner in color printing. To find an alternative to the costly and time-consuming process of hand coloring, he experimented with tinted lithography in the 1840s. A tinted lithograph, also known as a lithotint, is a monochromatic lithograph printed in several hues from one stone. However, although the method allows for printing numerous inks in various gradations, it cannot print bright, bold colors. Duval finally achieved success with true color printing, or chromolithography, in 1849, printing three or more colors from separate stones. His firm immediately began producing portraits, landscapes, illustrations, advertisements, and title pages with a wide variety of hues. His artists’ skillful reproductions of oil paintings, also known as “chromos,” became so popular that an entire industry arose in Philadelphia dedicated to manufacturing mass-produced, affordable replicas of paintings. Duval’s foremost “chromo” rivals included Thomas Sinclair (active 1838-81), Wagner & McGuigan (active 1845-57), and L.N. Rosenthal (active 1852-84). Overall, Duval and his contemporaries not only elevated lithography from a practical to a fine art but also helped make works of art more available to the multitudes.

The Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop

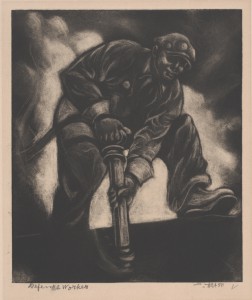

Continuing in the tradition of nineteenth-century printmaking firms, the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop (311 Broad Street) of the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project increased the accessibility of art to the public during the mid-1930s and early 1940s. The primary aim of this New Deal program was to provide employment to artists during the Great Depression. Yet it also sought to introduce art into the everyday lives of Americans by offering the use of its facilities and materials to the local community. It distributed editions to public institutions, such as schools, libraries, and post offices, and held exhibitions in unconventional spaces, such as parks, settlement houses, and subway stations, to allow people of all socioeconomic backgrounds the chance to encounter art outside of a museum or gallery.

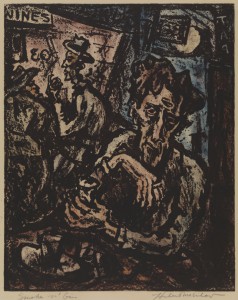

The Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop was the only graphic art center of the Federal Art Project specifically devoted to the creation of fine art prints. While other workshops manufactured commercial products, such as posters, brochures, maps, and charts, the artists of the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop created etchings, engravings, woodcuts, lithographs, dry points, mezzotints, and aquatints for their own creative endeavors. They saw printmaking not simply as a means of mechanical reproduction but as an imaginative process that helped them reconceptualize their approaches to art-making.

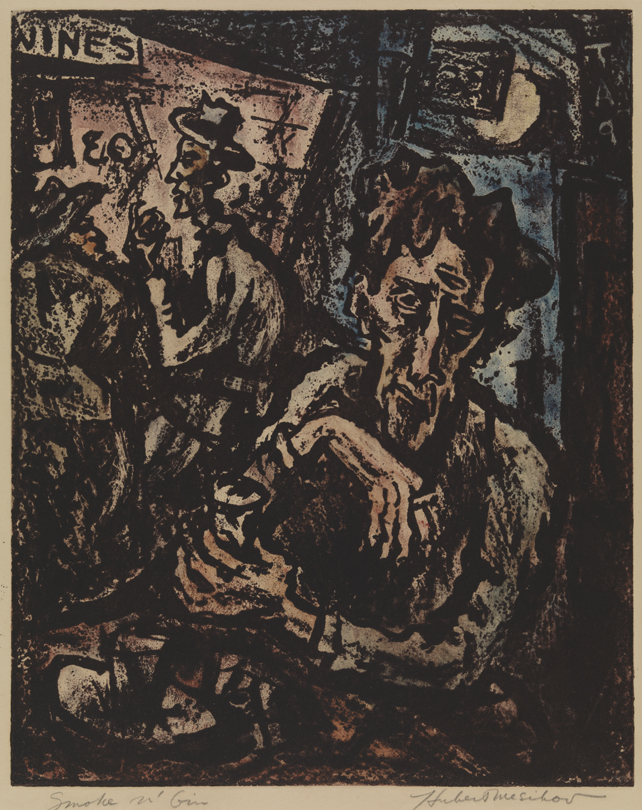

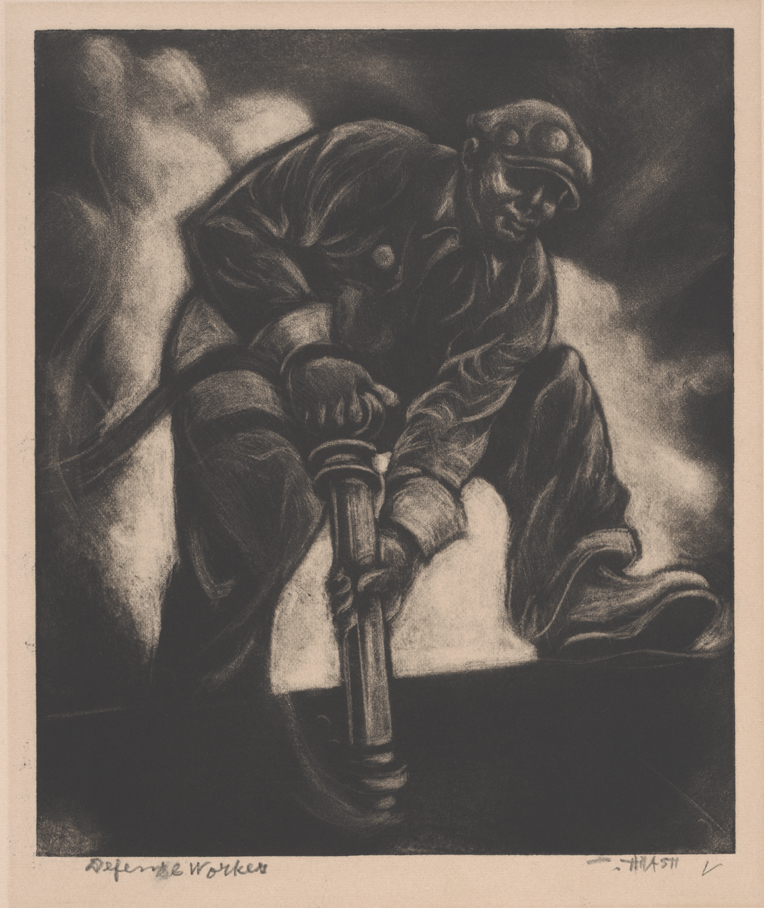

Furthermore, the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop was one of the most racially diverse graphic art centers in the country. African American artists such as Dox Thrash (1893-1965), Claude Clark (1915-2001), and Raymond Steth (1917-97) acquired unparalleled access to costly tools and equipment as well as to a community of artists with a wide range of technical expertise. In an oral history interview for the Archives of American Art, Philadelphia printmaker Hugh Mesibov (b. 1916) explained that a strong sense of community developed among workshop artists, regardless of race. They consistently shared knowledge and exchanged ideas as they explored the possibilities of printmaking technologies together.

As a result of this collaborative environment, the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop became a center of innovation. Its most significant accomplishment was the invention of the Carborundum printmaking technique, which the Philadelphia Tribune called “the first important innovation in the printmaker’s art in a century.” Carborundum is a coarse, granular industrial product traditionally used to clean lithographic plates. Thrash discovered its ability to produce images of great tonal richness while experimenting at the workshop in 1937. After rubbing the material onto a copper plate with a heavy flatiron, he realized that the Carborundum crystals created a rough, pitted surface that held ink. Mesibov, who was looking over his shoulder, suggested that he use a knife-like tool called a burnisher to polish the surface to create lighter tonalities. Thrash took Mesibov’s advice and sketched a nude. After this initial collaboration, Thrash and his colleagues continued to explore the artistic potential of Carborundum together, developing the Carborundum relief etching and the color Carborundum relief etching. Although these processes never gained popularity outside of the Philadelphia region, the Federal Art Project administration and newspapers across the country, from Time to Popular Mechanics to Magazine of Art, hailed the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop for its pioneering discovery. Approximately 108 Carborundum prints were created for the Federal Art Project between 1937 and the project’s termination in 1943.

Post-War Printmaking Centers

Building upon the legacy of the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop, artists founded numerous graphic art centers devoted to artistic collaboration and community engagement during the 1970s and 1980s, including the Fabric Workshop and Museum (1214 Arch Street), the Ettinger Studio (2215 South Street), and the Printmaking Center of New Jersey (440 River Road, Branchburg, New Jersey). Two of the most prolific, which continue to operate today, are the Brandywine Workshop (730 South Broad Street) and the Brodsky Center for Innovative Editions (Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, 33 Livingston Avenue, New Brunswick, New Jersey). The founder of the Brandywine Workshop, Allan Edmunds (b. 1949), studied with Sam Brown (1907-94), one of the African American artists employed by the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop.

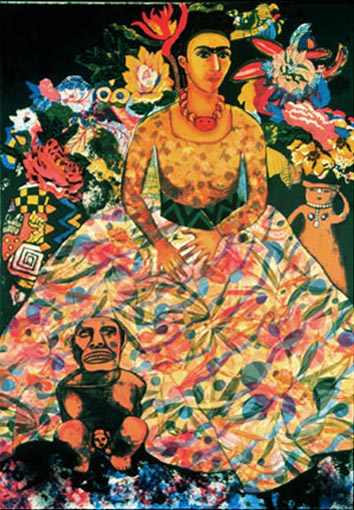

Like the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop, the Brandywine Workshop and the Brodsky Center have aimed to educate the public on printmaking processes through classes and lectures. Additionally, they have sought to introduce artists to new technologies by offering equipment and technical expertise for a wide range of methods, from traditional processes, such as etching, engraving, woodcut, and lithography, to more recent methods, such as electroplating, photo-emulsion screenprinting, and video imaging. Edmunds and Judith Brodsky, the founder of the Brodsky Center, have established non-hierarchical environments to encourage artists to work with printers, papermakers, students, and fellow artists. They believe that through such exchanges, artists will come across new, inventive ways to conceive of their work. The Brodsky Center, with its university location, has also taken on the role of a research facility where people can think creatively, develop ideas, and investigate alternative media.

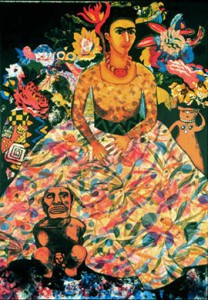

As the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop granted opportunities to artists who had been marginalized because of their race, the Brandywine Workshop and Brodsky Center have actively reached out to artists of color. Edmunds and Brodsky have recognized that few African American artists, especially women, have had the chance to master the technical processes of printmaking. Their artist residency programs have exposed artists of all backgrounds to the possibilities of media technologies and have provided extensive professional development. Since the time of their founding, over three hundred artists have passed through the doors of the Brandywine Workshop and the Brodsky Center, including Will Barnet (1911-2012), Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012), Barbara Chase-Riboud (b. 1939), Spencer Finch (b. 1962), William Kentridge (b. 1955), Glenn Ligon (b. 1960), Howardena Pindell (b. 1943), Faith Ringgold (b. 1930), Carolee Schneemann (b. 1939), Kiki Smith (b. 1954), Miriam Schapiro (b. 1923), Mickalene Thomas (b. 1971), and Carrie Mae Weems (b. 1953). Through their emphases on creative collaboration and technical innovation, the Brandywine Workshop and Brodsky Center have built upon the rich legacies of Peter S. Duval and the Philadelphia Fine Print Workshop to continue the tradition of printmaking in the Philadelphia region.

Michelle Donnelly earned her M.A. in Art History from the University of Pennsylvania. As a Curatorial Assistant at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, she curated the exhibition “Art for Society’s Sake: The WPA and Its Legacy” in 2013. She is a Samuel H. Kress Interpretive Fellow at the Morgan Library & Museum in New York.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- The Brodsky Center

- The Brandywine Workshop

- Descriptive Terminology for Works of Art on Paper (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- "An Exuberant Bounty: Prints and Drawings by African Americans" (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2010)

- "Sept. 9-Dec. 11: 'Old Master Prints and Drawings' on view in Old College West Gallery" (UD Daily, August 18, 2015)

- Philadelphia on Stone: The First Fifty Years of Commercial Lithography in Philadelphia, 1828-1878 (Digital Exhibit, Library Company of Philadelphia)