Shipbuilding and Shipyards

Essay

Perhaps no business, industry, or institution illuminates the history of the Greater Philadelphia region from the seventeenth century to the present day more clearly than shipbuilding and shipyards. This may seem surprising since Philadelphia and nearby Delaware riverfront ports lie one hundred miles from the Atlantic Ocean up an often treacherous Delaware Bay and river filled with shifting sandbars and an ever-changing deepwater ship channel. Ice often closed the river for several winter months to ship navigation and travel. Moreover, strong tides and winds made sailing up the river to Philadelphia before the age of the steamboat very difficult. Why then did Philadelphia and surrounding southeastern Pennsylvania, Delaware and New Jersey riverfront ports develop shipyards and become one of the greatest shipbuilding regions in the United States?

As early as the 1640s Swedish boat builders fabricated several small craft on the Delaware River in their short-lived New Sweden colony, but large-scale shipbuilding started when William Penn (1644-1718) settled his great proprietary grant of Pennsylvania between 1681-1682 with skilled Quaker artisans and maritime merchants escaping the religious persecution (sufferings) in old Britain and seeking economic opportunity in the New World. In fact, six years before he founded Philadelphia, Penn had helped shipwright James West (d. 1701) develop a small shipyard in 1676 along the Delaware Riverfront in what later became Vine Street in the city of Philadelphia. Meanwhile, Penn recruited Welsh, Irish, Scot and English Quaker craftsmen who were involved in shipbuilding in Bristol, England, and more fully along the Thames River, already by 1682 a great center of ship construction and merchant houses. Indeed the Southwark section of London’s Thames riverfront soon gave rise to the Southwark shipbuilding and merchant community along the Delaware riverfront of Philadelphia. When the Philadelphia riverfront became too crowded with merchant docks and buildings for establishment of shipyards, many shipwrights moved a few miles upriver to the Kensington neighborhood that soon rivaled Southwark as a shipbuilding center on the Delaware River.

The first settlers of Penn’s colony turned to shipbuilding as a major industry because they found an abundant supply of trees, particularly live oak for masts, pine for hulls, and pine tar for caulking both across the river in the West New Jersey colony and in the nearby interior of Pennsylvania woodlands. Deposits for iron forging of anchors, nails and other ship parts was discovered nearby. A lucrative trade in lumber, furs, and agricultural products soon developed that demanded the construction of local ships far more cheaply, and in many cases better, than in Britain so that Pennsylvania and West New Jersey merchants across the river might carry on trade to Europe, Africa and the West Indies.

Flurry of Shipbuilding

Demand for merchant ships, particularly scows, sloops, brigs, and schooners, created a flurry of shipbuilding along the Delaware riverfront. By 1720 there were at least a dozen shipyards in Philadelphia and the surrounding waterfront producing wooden sailing ships of up to 300 tons. Around these private yards, workers’ housing, taverns, churches, and shops developed to form a vibrant riverfront community. Leading merchant houses operated docks and warehouses in the neighborhood, creating great wealth for Philadelphia. By 1750, Philadelphia with its cheaper labor, skilled ship carpenters, iron forges, and an abundance of trees had replaced Boston as the major colonial shipbuilding center.

The Colonial era was in some ways the golden age of Philadelphia shipbuilding, with master shipbuilders and carpenters including Joshua Humphreys (1751-1838), Manuel Eyre (1736-1805), the Wharton family, and Penrose brothers designing and building fast coastal sailing ships and Atlantic brigantines. The approach of troubles with Great Britain in the 1760s, though, connected in part to American colonial violations of British navigation laws and maritime regulations, threatened Philadelphia’s shipbuilding primacy. As affairs moved toward protest and then revolt, Philadelphia became the center of a Continental Congress that required naval defense. Benjamin Franklin’s Committee for the Defense of the Delaware raised money for small gunboats of the Pennsylvania Navy to defend the river and city. Meanwhile, the Continental Congress raised money for the Continental and later a U.S. Navy. These developments stimulated Philadelphia shipbuilding that included the construction of many small row gunboats, floating batteries, and even four innovative fast frigates. These frigates, designed by naval architect and Southwark shipbuilder Joshua Humphreys, became the prototype of the U.S. Navy’s first 44-gun frigates such as the Constitution.

British occupation of Philadelphia in 1777-78 set back Philadelphia shipbuilding. Frigates were burned, gunboats sunk, and tiny riverfront shipyards from Southwark to Kensington closed. But after British evacuation of the Continental capital, shipbuilders returned to construct warships for the revolutionary government. Independence and Philadelphia’s dominance of the China trade gave local shipbuilders, most notably the Grice shipyard, contracts to construct fast China traders and frigates for the U. S. Navy. Indeed, the old Humphreys and Wharton shipyard in Southwark served between 1794 and 1797 as the site for construction of the 1,576-ton, 44-gun frigate United States for the U.S. Navy. In 1801, the Southwark yard became the location of the first Philadelphia Navy Yard.

However, after the brief revival of shipbuilding during the Federalist era, Philadelphia maritime prominence fell on hard times. Britain closed the West Indies trade to American ships. The wars of the French Revolution created problems for American neutral trade. Jefferson and the Republicans advocated a coastal defense and a gunboat navy and refused to fund the deepwater navy of larger warships, while in 1807 instituting an Embargo against all but coastal American shipping. Meanwhile, New York and Baltimore began to take prominence both in trade and in shipbuilding. The War of 1812 momentarily revived Philadelphia’s shipbuilding as private Delaware River shipyards secured contracts for Jeffersonian gunboats and privateers, while the Humphreys and Penrose shipyard, adjacent to the Southwark Navy Yard, constructed gunboats and laid the keel for the 74-gun ship Franklin.

Shipyard Setbacks

Philadelphia had lost its leadership in overseas trade by the time of the War of 1812, and Delaware River shipyards suffered setbacks. Many small privately owned yards simply ceased to construct boats or ships. Nevertheless, a number of early 19th century industrial and economic developments revived Delaware River shipbuilding in the years before the Civil War. An abundant supply of Pennsylvania coal promoted steam powered technology most notably development of the railroad across the river in New Jersey (the Camden and Amboy Railroad) and in Pennsylvania. Moreover, machine shops, iron forges, textile, and other industries blossomed in the region, and much of it contributed to the reorganization of shipyards into larger industrial plants, subcontracting with machine shops, iron and later steel producers. This meant that the small craft shipyards of colonial times would eventually be replaced by larger industrial firms.

The first to recover and adopt a larger corporate organization was the Philadelphia Navy Yard along the Southwark riverfront. With government contracts, the yard was able to build machine shops on site. It meant that the navy yard could experiment with the innovative screw propeller technology of John Ericsson (1803-89), building the trailblazing first propeller driven warship, Princeton. The screw propeller one day replaced all paddle side-wheeled warships that were so vulnerable to cannon fire. At the same time, the yard built two huge covered ship houses that allowed wooden warships to be under construction continually with a year-around skilled workforce protected from the weather. This led to the construction of the largest wooden warship ever built for the U.S. Navy, the 120-gun Pennsylvania, launched in 1837.

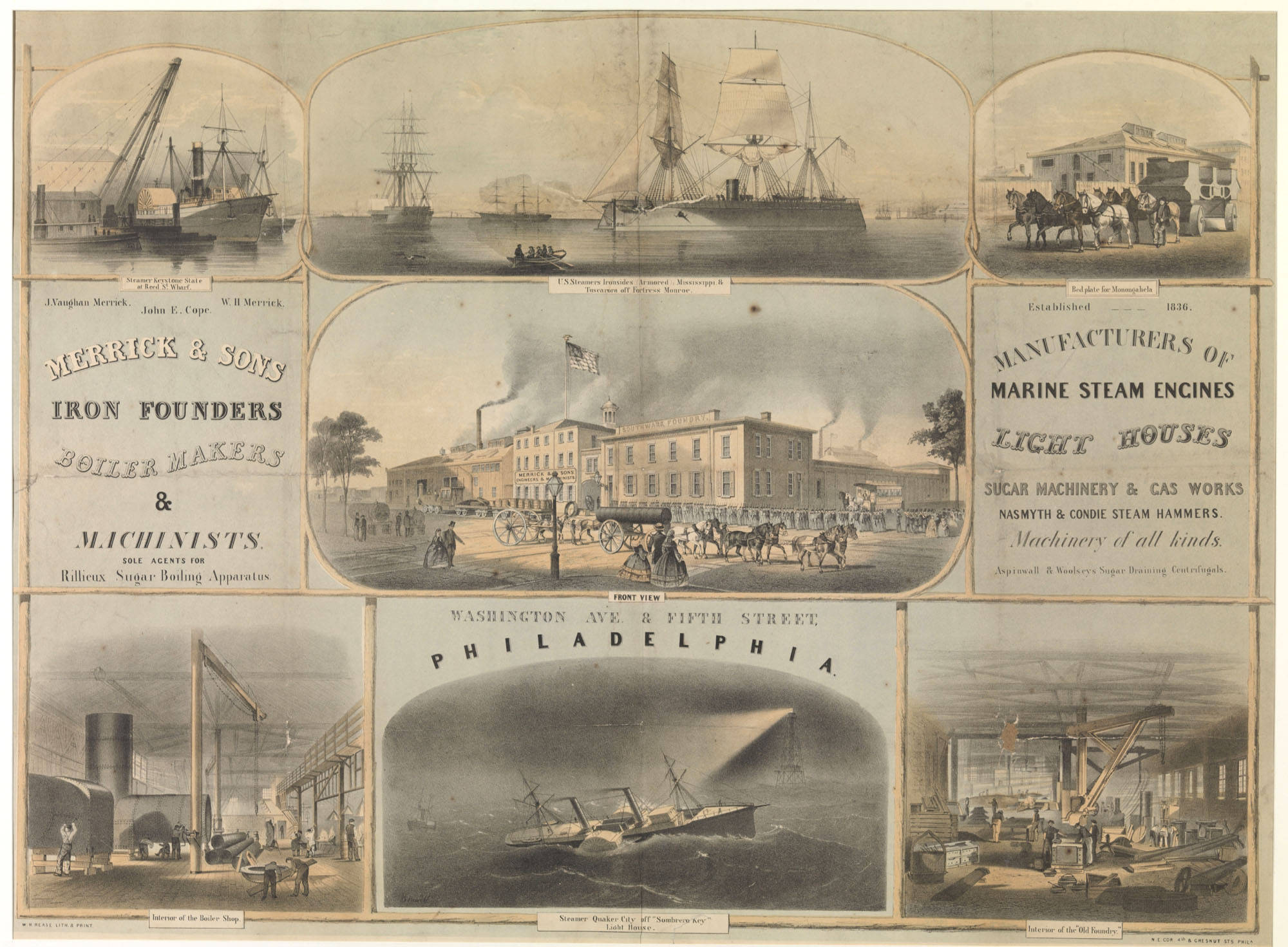

Meantime, a private shipbuilding yard was organized by the Cramp family on the Kensington waterfront that would become one of the most important shipyards in Philadelphia and American history. In the years before the Civil War, the William Cramp (1807-79) & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company began assembling wooden sloops, tugs, schooners and passenger ships, many powered by steam. As the Cramp’s yard expanded, it became a modern industrial plant, incorporating all the latest technology in propulsion, steam engines and hull design, and iron siding. It worked with the Philadelphia engineering firms of Merrick and Towne, Reaney & Neafie (and Levy) and Richard Loper (1800-81), the latter a pioneer of contract shipbuilding and an inventor of innovative curved screw propellers for ships. In 1849 Cramps launched Caroline, claimed to be the fastest propeller driven vessel in the world. This also prepared the firm to build one of the first great battleship during the Civil War, New Ironsides, and several innovative iron turret ships (monitors) for the U.S. Navy in its battle against Confederate ironclads. The Philadelphia Navy Yard was not far behind, building monitors and experimenting during the Civil War with steel plating and steam engines. Soon, the government yard (that also housed the U.S. Marine Corps) became overcrowded in the Southwark neighborhood. Shortly after the war the U.S. Navy began to relocate its plant and lay up iron monitors in a wet basin at League Island just down river. After Philadelphia presented the site as a gift in 1868 to the federal government, the U.S. Navy moved the navy yard entirely by the mid-1870s to this island located at the confluence of the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers.

More Decline After Civil War

Post-Civil War Philadelphia suffered a shipbuilding depression. Skilled shipyard workers were laid off, machine shops closed, the Navy Yard was in transition, with no shipbuilding dry dock yet dredged, and the fading of an entire wooden shipbuilding craft. But the Cramp shipyard kept Philadelphia’s shipbuilding industry alive, constructing iron tugs to tow Pennsylvania coal barges, fast propeller-powered steamships, and other commercial vessels. The Kensington yard was, thus, in a perfect position to join the large contracts that the government issued to construct the New Navy to compete in the late 19th-century world of imperialism.

The first shipyard on the Delaware River to benefit from the U.S. drive to compete with European navies to secure overseas empire was actually John Roach’s (1815-87) Delaware River Iron Shipbuilding and Machine Works downriver in Chester, Pennsylvania, supported by the machine shops and industries of Wilmington, Delaware. The yard laid the keels for the “ABCD” warships of the New Navy (Atlanta, Baltimore, Charleston, and Dolphin). The Roach shipbuilding company ran into financial problems, however, and Cramp, with intimate political connections, took over contracts for future iron and steel shipbuilding. Cramp became during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries the most significant shipyard in the United States, constructing modern battleships, cruisers, and torpedo boat destroyers for the U.S. Navy and warships for Latin American and Russian contractors. Its corporate organization, subcontracting to dynamic Philadelphia industrial firms and receiving U.S. government support propelled the yard to the center of American naval development. Several U.S. presidents attended ship launchings, attesting to the Philadelphia yard’s political and naval importance. At the same time the Philadelphia firm built innovative modern Atlantic commercial steamships, passenger, and cargo vessels.

By the First World War (1914-18) Cramp was the most important shipbuilding place along the Delaware. But there were major competitors. In 1899, New York shipbuilder and Wilmington, Delaware ship engineer Henry G. Morse (1850-1903) located his New York Shipbuilding Corporation’s shipyard in Camden, New Jersey, just across the river from the old Southwark navy yard. Soon, his innovative template construction and shipbuilding methods began to overshadow the assembly system at the Cramp’s industrial plant. At the same time, the Philadelphia Navy Yard, now on League Island, built modern dry docks, machine shops, and other support facilities, making it competitive with private shipyards. With three great shipyards in the Philadelphia area during World War I it was inevitable that the region would become a major contributor to the naval war effort. Moreover, the Sun Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Corporation (founded in 1916) of Marcus Hook, below Philadelphia, the Pennsylvania and New Jersey (later Pusey and Jones) Shipyard of Gloucester City, New Jersey, just below Camden, and the federal shipyard of Pennsylvania on Hog Island, below the city, constructed tankers, cargo ships, and troop transports. Entire shipyard worker communities including Yorkship and Morgan villages in Camden City and Noreg Village (later Brooklawn), Camden County, New Jersey, were founded around the shipbuilding industry. These villages provided homes for laboring families of Irish, Italian, and Eastern European, mostly Polish, descent.

Strike Disruptions

But if war stimulated shipbuilding, the postwar era and accompanying economic depression devastated the industry in Philadelphia. Cramp closed in 1927 in bankruptcy. Owing taxes to the city of Philadelphia, the yard decayed and the plant rotted away. Labor unrest and strikes by shipyard workers unionized under the Industrial Union of Marine and Shipbuilding Workers of America disrupted shipbuilding. Yet, the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration kept shipbuilding alive in Philadelphia. The Navy Yard received government contracts for treaty cruisers allowed under the post World War I naval disarmament agreements, and also to modernize old battleships mothballed in the wet basin on League Island. Philadelphia’s commercial port actually prospered during the economic setbacks of the 1930s, with 300 wharves doing business. And, having supported Roosevelt’s presidency, Philadelphia and Camden received funding for naval ship construction both at the New York Shipbuilding company of Camden and the Philadelphia Navy Yard on League Island. As international crises led to a second world war, Philadelphia received more huge contracts to build modern warships, and in 1939, for construction of the first of many Federal Defense Housing projects for shipyard worker housing, including that for African-Americans and women. During the war, shipyard workers also sought housing in rural suburban communities surrounding the overcrowded urban shipbuilding centers of Philadelphia, and Chester, Pennsylvania; Camden, and Gloucester City in New Jersey and the Wilmington, Delaware region.

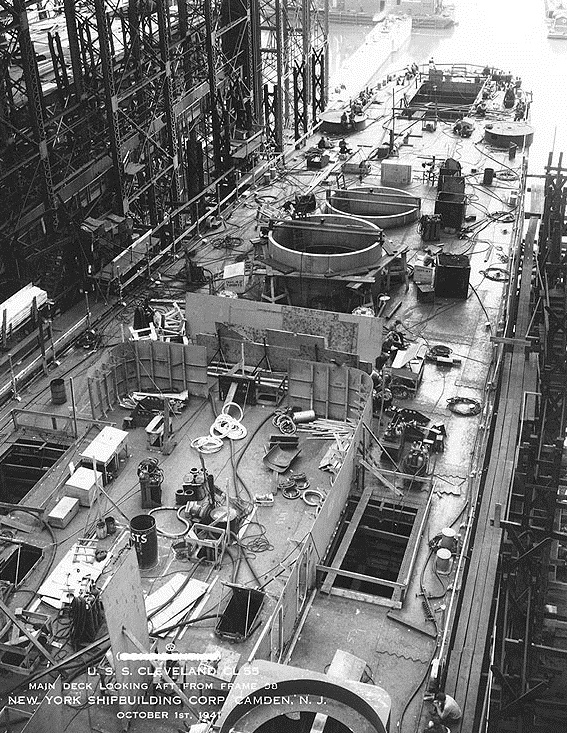

World War II was arguably the most important period for Philadelphia and Delaware valley shipbuilding as part of its place as the Arsenal of Democracy. The Philadelphia Navy Yard employed over 50,000 workers, including several thousand “Rosie the Riveters.” Indeed, women comprised 16 percent of the shipyard’s workforce. The yard built two great battleships New Jersey and Wisconsin, and over fifty warships including innovative torpedo (PT boats) and fast aircraft carriers. Meanwhile, New York Ship hired more than 30,000 workers who constructed battleships, aircraft carriers, and destroyers. Nearby Camden Forge and RCA Victor of Camden, New Jersey received large contracts to provide forgings and electronics for warships constructed in the greater Philadelphia region. Sun Shipbuilding of Chester expanded to twenty shipways and employed nearly 40,000 workers at its four yards. One of Sun Ship’s yards employed mostly African-Americans

Cramp Shipbuilding Company revived momentarily, as well, with 18,000 employees to produce naval vessels, mostly light cruisers, ocean tugs, and submarines. However, Cramp closed permanently after the war. New York Ship and the Philadelphia Navy Yard stayed alive for years with government contracts. New York Ship built several modern postwar warships, including the aircraft carrier Kitty Hawk. It launched the first (and only) nuclear-powered merchant ship Savannah and signed government contracts to construct nuclear submarines. New York Ship became the area’s largest postwar employer. However, mismanagement, labor unrest, construction accidents on the carrier, and growing restrictions on building nuclear warships so near a great city led to the closing of the Camden shipyard in 1967, contributing to growing economic and social problems in the city. The South Jersey Port Corporation assumed control of the old shipyard in 1971 and operated it as the Broadway Terminal, handling millions of tons annually of lumber, fresh fruits, scrap metal. Meantime, Sun Ship was sold to the Pennsylvania Shipbuilding Corporation (Penn Ship) and operated until closure in 1989. The former Penn Ship site soon hosted a cargo terminal, casino, racetrack, and a penitentiary.

Military Shipbuilding

The Philadelphia Navy Yard continued to build ships for the U.S. Navy including U.S. Marine Corps assault ships, and received Service Life Extension Program (SLEP) contracts to modernize conventionally powered (non-nuclear) aircraft carriers. But the yard could not support a nuclear navy since during World War II an accident in the uranium enriching plant on base had forecast the potential for a nuclear accident in the Delaware Valley. Without the ability to either build or modernize a nuclear navy, Philadelphia’s navy yard gradually became an outdated relic and closed for shipbuilding in 1996. The city of Philadelphia assumed ownership of the old navy yard in 2000, and in order to provide employment for the thousands of laid off shipyard workers in the region contracted with the Kvaerner shipbuilding corporation of Oslo, Norway to use the large dry docks of the 450-acre closed Philadelphia Naval Shipyard to construct modern tankers and container ships for Exxon and other companies. At the same time, the U.S. Navy leased the old wet basin and part of the former navy yard’s historic center for its Naval Facilities Engineering Command Mid-Atlantic and its Naval Inactive Ship Maintenance Facility to lay up warships, including obsolete battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers and destroyers for scrapping or removal as historic sites.

Meanwhile, the city of Philadelphia started to develop a plan to transform the 1,000-acre industrial plant on League Island into a multi-purpose post-industrial business, shopping, and tourism park. And, when Kvaerner encountered financial troubles that forced the Norwegian shipbuilder to merge with the Aker shipbuilding firm of Oslo, Norway, the Philadelphia and U.S. governments became partners with the private Norwegian firm to ensure the continuation of shipbuilding along the Delaware River. Soon, Aker began the construction of Aframax tanker hulls for SeaRiver Maritime, Inc. in the two great dry docks at the former navy yard. This public-private partnership to promote the construction of ships on the Delaware River revealed once again how important shipbuilding was and continues to be for the history of the greater Philadelphia region.

Jeffery M. Dorwart is the author of histories of the Philadelphia Navy Yard; Fort Mifflin of Philadelphia; Naval Air Station Wildwood; Camden and Cape May Counties, New Jersey; Office of Naval Intelligence; Ferdinand Eberstadt and James Forrestal. Dorwart is Professor Emeritus of History, Rutgers University.

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- West Shipyard Archaeological Study

- Sail Drawing of the USS Constitution (National Archives)

- Oh, Give us a Navy of Iron (Sheet Music) Dedicated to Capt. John Ericsson (Duke University)

- Iron Ship-Building in the United States. The Ship-yards of William Cramp & Sons of Philadelphia (Library of Congress)

- League Island U.S. Navy Yard, Philadelphia (Library of Congress)

- The Navy's Service Life Extension Program (United States Government Accountability Office)

- Philadelphia Naval Shipyard Historic American Building Record (Library of Congress)

- Creating the Continental Navy, Glenn Grasso (C-Span)