Redlining

Essay

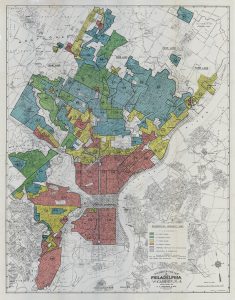

Redlining, the practice of basing access to capital and financial services on neighborhood characteristics such as race and ethnicity, had destructive effects on older, nonwhite areas of Philadelphia. Especially in areas of South, West, and Lower North Philadelphia that form a ring around downtown, banks and other lending institutions issued proportionally fewer mortgages than in other parts of the city. In doing so, lenders perpetuated a cycle of disinvestment that damaged individual property owners and entire neighborhoods.

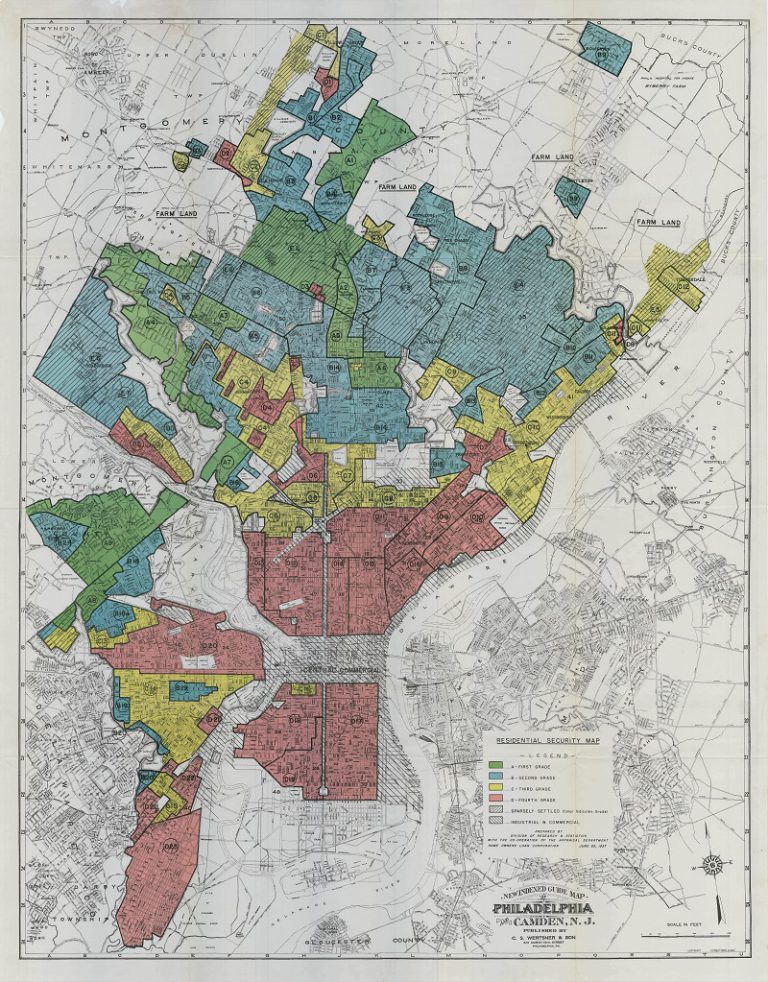

The term “redlining” arose in the 1960s, although the practice of redlining dates back to the 1930s and two federal housing agencies – the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). HOLC employed local real estate and finance experts to conduct systematic neighborhood appraisals in the 1930s and used the survey data to create Residential Security maps representing the perceived neighborhood risk. The riskiest neighborhoods received a grade “D” and were colored red. The nature of Philadelphia as an industrial city, and the close proximity between factories and residential areas, led to many neighborhoods receiving the lowest grade as high-risk areas.

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) Mortgage Insurance Program based its underwriting guidelines on maps that coded as “red” those geographic areas considered too risky to warrant mortgage lending. According to FHA underwriting manuals, the main characteristics elevating that risk were the age of housing and the race or ethnicity of residents. Those manuals, which included language that discouraged lending to homebuyers who would upset the racial character of a neighborhood, broadly influenced the underwriting standards adopted across the entire mortgage industry. Almost immediately, these practices reduced access to mortgages in older and non-white neighborhoods, particularly in North, South, and West Philadelphia.

Redlining made it difficult for individuals to purchase homes and to borrow against the value of homes they owned. It affected whole neighborhoods, reducing owner occupancy, lowering property values, decreasing housing quality, and increasing racial segregation. Difficulty accessing credit also limited the ability of homeowners to finance home repairs, which decreased their buildings’ quality and market value. The lack of access to mortgage capital often led to houses being converted into commercial properties and apartments.

Redlining affected not only the inner ring of working-class neighborhoods but also the streetcar suburbs of West and North Philadelphia, which had been built along transit lines to house families who could afford to escape from the gritty industrial core. Solidly middle class by the 1920s, after World War II the streetcar suburbs experienced a mass exodus to automobile suburbs.

Strawberry Mansion, for example, had developed in the late 1800s at the edge of Fairmount Park in North Philadelphia. Easy access by streetcar to downtown, along with amenities like Fairmount Park and Shibe Park baseball stadium, had drawn many families in the early twentieth century, most notably a burgeoning Jewish community. From the 1940s to the 1960s, after many white residents took advantage of FHA mortgage insurance for buyers of new suburban homes, Strawberry Mansion’s population changed from 89 percent white and 11 percent Black, to 5 percent white and 95 percent Black. Because Strawberry Mansion was redlined, sellers had fewer and less-generous offers from buyers, triggering a decline that continued for decades.

A similar exodus occurred in the Mill Creek section of West Philadelphia, on the north side of Market Street between Forty-Fourth and Fifty-Second Streets. Named for a creek that was buried in the nineteenth century, Mill Creek had been developed after 1880 as a streetcar suburb served by two commercial thoroughfares, Lancaster and Haverford Avenues. As Dick Clark (1929-2012) was broadcasting American Bandstand from a studio in this neighborhood at Forty-Sixth and Market Streets, redlining was undermining the housing stock and fueling outmigration to the suburbs, mainly by whites. In 1950, the population of Mill Creek was about one-quarter white and three-quarters Black. By 1970 white residents made up only 4 percent of the population.

Regional housing activists fought back against the damaging effects of discrimination in access to housing and credit. In Delaware County as early as 1956, civil rights activist Margaret Collins (1908-2006) established Friends Suburban Housing Inc. in response to unequal access to homeownership. That organization subsequently merged with other groups and changed its name to the Housing Equality Center, while expanding its geographic focus to encompass all the Pennsylvania counties of greater Philadelphia and targeting housing discrimination based on race, disability, and age.

By the mid-1970s, the mutually reinforcing trends of population loss and disinvestment had created levels of vacancy and abandonment that the city had never witnessed before. A trio of Philadelphia bank executives, in cooperation with the Greater Philadelphia Urban Affairs Coalition, saw the need to do more than prohibit discrimination in lending. In 1975 First Pennsylvania Bank, Philadelphia Savings Fund Society, and Philadelphia National Bank established the Philadelphia Mortgage Plan, which became a national model of how banks could act affirmatively to stabilize housing values and increase homeownership opportunities. In contrast to banks’ traditional practice of denying mortgages based on conditions prevailing across a neighborhood, the new plan looked only at the single block on which the house was located and took into account its community assets, such as the positive influence of a strong neighborhood organization or a nonprofit developer. Unlike other lenders, the plan treated welfare payments as reliable income sources for purposes of granting a mortgage. The plan’s success drew additional banks to join and triggered a name change to the Delaware Valley Mortgage Plan as it expanded to the suburbs. By the mid-1990s, the DVMP was making about one quarter of its loans to suburban borrowers. Using flexible underwriting standards, participating banks made thousands of mortgage loans at below-market rates.

A Nationwide Problem

Not just a Philadelphia problem, redlining continued to be widespread across the United States after the Fair Housing Act of 1968 made it illegal. Congress acted in the mid-1970s to pass the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA). These laws provided significant help to housing activists by assigning banks an affirmative obligation to provide mortgage credit to borrowers in communities where they were doing business and decreeing that federal bank regulators could grant permission for banks to shift their branch locations or merge with other banks only when those banks demonstrated a record of providing fair credit throughout their business area. That gave housing advocates a vehicle to launch public protests against discriminatory lenders who applied for regulatory approvals.

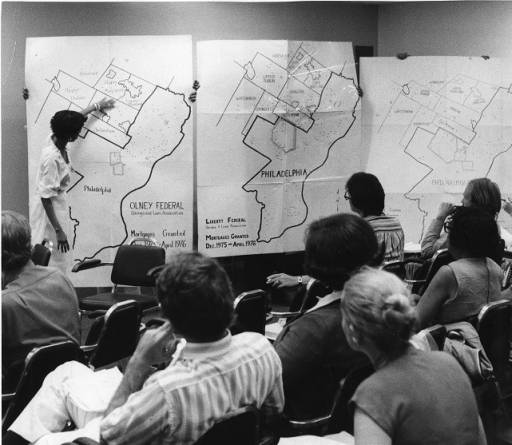

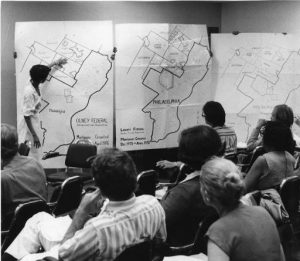

During a wave of bank mergers in the 1980s, coalitions of community, church, and research and advocacy groups seized the opportunity to gain greater access to mortgages for distressed areas. They forced banks to increase their lending in underserved neighborhoods if they wished to avoid lengthy delays and bad publicity. For example, in 1986 Community Legal Services spearheaded a complaint brought by the Eastern North Philadelphia Initiative, a coalition of thirty-seven church, community, and advocacy groups protesting Fidelity Bank’s acquisition of Industrial Valley Bank. They charged that Fidelity had failed to meet Community Reinvestment Act requirements. The protesters forced Fidelity to pledge its “best efforts” to provide financing at below-market rates for purchasing and renovating homes and small apartment buildings in distressed areas.

Also in 1986, the Philadelphia office of ACORN (Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now) threatened to oppose Continental Bank’s merger with Midlantic Bank. That threat, later withdrawn, was enough to motivate senior Continental officials to visit ACORN’s office in North Philadelphia and promise millions in loans to distressed neighborhoods. In 1989 ACORN challenged Provident National Bank’s proposal to buy the Bank of Delaware, seeking an agreement similar to the one reached with Continental Bank. ACORN staged a protest outside a downtown bank branch, complaining that from 1983 to 1987 Provident’s lending in majority-Black areas had declined from 40 percent to only 27 percent of its loan portfolio. While Provident did not sign a joint agreement, it did volunteer to make $25 million in new loans.

Subprime Lending

A different, yet also damaging, form of discrimination emerged in the mid-1990s. Rather than denying credit, some lenders targeted inner city neighborhoods to offer mortgages to low-income and minority borrowers at far less favorable terms than were applied to conventional loans. Marketed intensively in inner-city neighborhoods, these “subprime” loans hid in fine print the dramatic escalation in monthly payments after the first two or three years of the loan period. Many lenders sold such loans to the same kinds of low-income and minority homebuyers they had previously shunned. The ballooning payments built into these loans drove thousands of borrowers into default and foreclosure on their homes. Since lenders had sold a disproportionate share of subprime loans in minority communities, those neighborhoods suffered unusually high foreclosures and multiplying vacancies.

Philadelphia City Council took action in 2008 to create Philadelphia’s Residential Mortgage Foreclosure Diversion Program, one of the nation’s first programs to forestall foreclosures. Before lenders could foreclose on homeowners in default, the city mandated that the parties engage in a face-to-face meeting to negotiate a workable repayment agreement. Every homeowner facing a default filing was offered counseling and sometimes legal representation. The program, which helped a majority of participants to stay in their homes, became a national model.

Despite such strides, unequal lending practices continued. Some lenders continued to discourage applications from minority neighborhoods by refusing to locate branch offices near them. In 2015 the civil rights division of the U.S. Department of Justice charged that Hudson City Savings Bank operated so few branches in minority neighborhoods of Philadelphia, Camden, and Wilmington that few Black or Hispanic borrowers ever applied for mortgage loans. In Camden County, for example, Hudson Bank relied on forty-seven brokers to originate mortgages, but not a single broker was based in a minority neighborhood. Hudson City agreed to a settlement that required the bank to improve access to responsible and affordable credit to qualified borrowers in Black and Hispanic neighborhoods.

In a society where homeownership often served as the most common route to building wealth, the denial of mortgage loans and the predatory use of subprime credit inflicted substantial damage on families, especially in minority communities. They contributed to widening wealth gaps in the second half of the twentieth century that profoundly influenced many Philadelphians’ life chances.

Kristen B. Crossney is Associate Professor of Public Policy and Administration at West Chester University of Pennsylvania. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Redlined zoning code draft proposes more changes (WHYY, January 18, 2011)

- How a poverty study speaks to all races in Philadelphia (WHYY, July 29, 2013)

- Housing jargon, explained (WHYY, December 8, 2015)

- Obama administration announces new housing segregation rules (WHYY, July 8, 2015)

- At Philly archive's new home, redlining mural charts dismal chapter of city history (WHYY, December 7, 2018)

Links

- Mapping Inequality: Redlining in New Deal America: Philadelphia (University of Richmond and Project Partners)

- Pennsylvania Housing Equality Center History

- Civil Rights in a Northern City: Philadelphia (Temple University)

- Margaret H. Collins Papers And Biographical Overview (Swarthmore College)

- U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Greater Philadelphia Urban Affairs Coalition

- These 5 Neighborhood Maps Show Roots of Gentrification (Next City)