Riots (1830s and 1840s)

Essay

In the 1830s and 1840s, as social and economic tensions arose from early industrialization and from a population that was at once growing rapidly and becoming more racially and religiously diverse, Philadelphia experienced a sharp increase in disorder that it was unprepared to handle. The fragmentation of Philadelphia County into numerous municipalities and the absence of a professional police department allowed demonstrations to escalate into full-scale riots. The city’s inability to quell those riots ultimately led to consolidating twenty-nine jurisdictions into one municipality and creating one the nation’s earliest modern police forces.

During these two decades, industrialization and surging immigration brought increased labor competition and ethnically mixed settlement patterns to the city. The population more than doubled from 161,410 to 388,721 and spilled beyond the original city limits (from South to Vine Streets between the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers) in all directions, which put a strain on the city not designed to accommodate such rapid growth. The increasing number of Black residents and the rise of abolitionism in the early 1830s added to the tension. The Black population in Philadelphia and its surrounding suburbs more than doubled in the first three decades of the nineteenth century, from 6,880 in 1800 to 15,624 in 1830. Coinciding, but not caused by this growth, was the increase in the abolitionist movement.

These factors combined to create a volatile environment that finally boiled over in the summer of 1834. On August 11, 1834, white and Black citizens quarreled over seats on a merry-go-round known as the “flying horses” near Seventh and South Streets. The next evening, as rumors spread that Black residents had insulted whites, fighting resulted in the destruction of the carousel. Later that night a group of whites assembled just outside the Moyamensing quarter, which had a significant portion of Black residents, and moved into the community smashing Black residents’ taverns, homes, and furniture. Philadelphia constables and watchmen, called in to assist the helpless watchmen of Moyamensing, successfully broke up the mob and arrested nearly twenty rioters. However, destruction continued over the next two days as white mobs tore down a Black church in Southwark, sacked the First African Presbyterian Church, destroyed more than thirty Black homes, and beat any Black citizen in their path. Despite more than forty arrests and the mayor’s attempt to prevent violence, the undermanned constabulary and underprepared city could do little to prevent the devastation. Minor skirmishes continued over the next few days, but Philadelphia’s first widespread race riot ended on August 14, 1834.

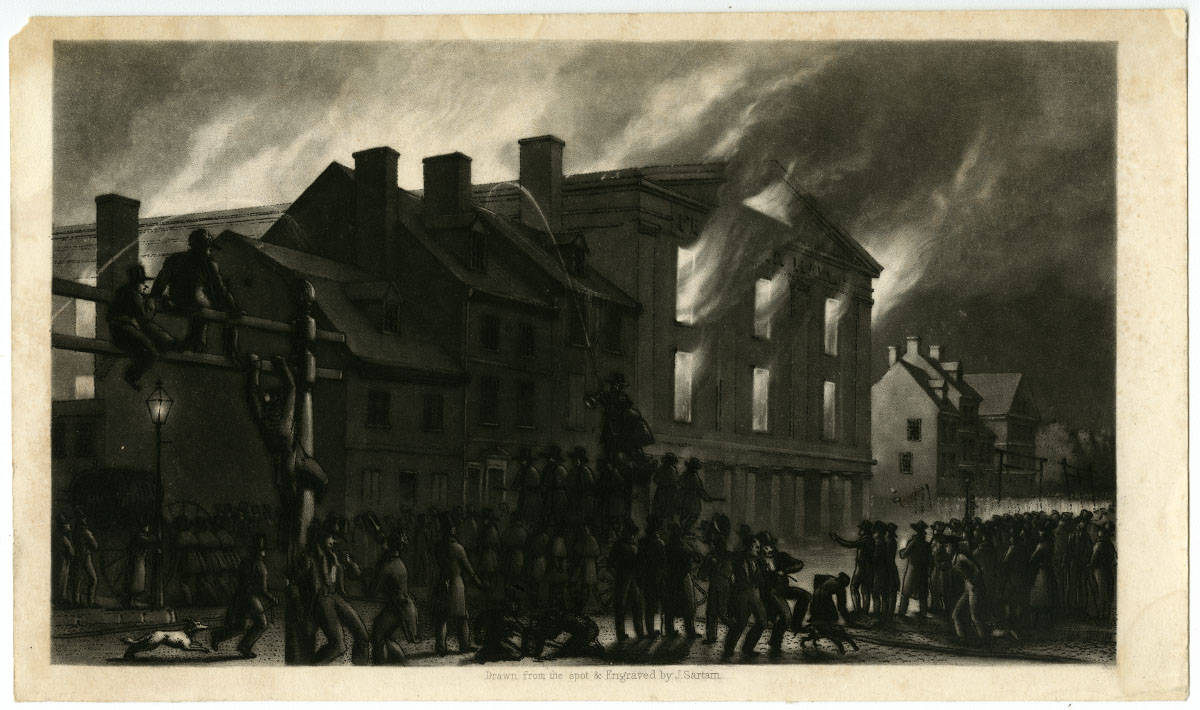

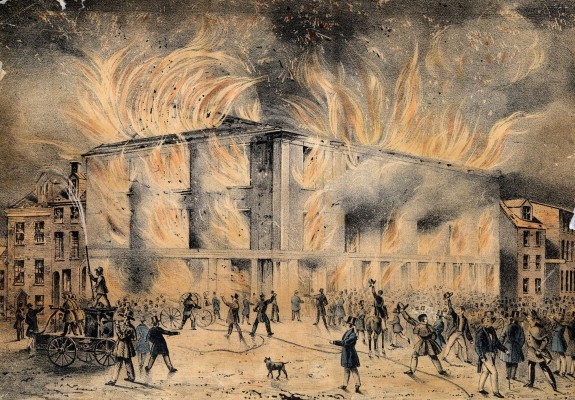

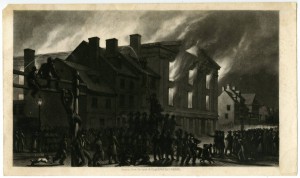

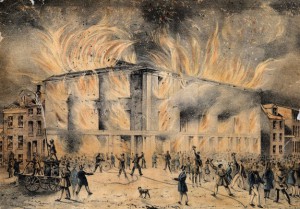

Anti-abolition sentiment and racial tensions did not dissipate over the next four years. In fact they grew worse because of the rise of the national abolition movement, the Panic of 1837, and the Pennsylvania State Constitution of 1838, which rescinded the free Black vote. While the new constitution may have placated the white population, it added resolve to the fight for Black rights and further intensified the racial discord of the city and its surrounding suburbs. Abolitionists within the city, not deterred, constructed a meeting hall known as Pennsylvania Hall on Sixth Street near Franklin Square. It opened on Monday May 14, 1838, with national abolitionist leaders such as William Lloyd Garrison (1805-79), Maria Chapman (1806-85), and the Grimke sisters in attendance. The opening day went off with little disturbance, but by Tuesday night notices spread throughout the city to protest in front of Pennsylvania Hall. By Wednesday night a mob gathered outside the building and broke windows as Angelina Grimke (1805-79) spoke to a predominately female audience inside. Although the meeting abruptly ended and the Thursday program was canceled, it was not enough to save the hall. Late Thursday evening a crowd of nearly three thousand gathered in front and set the structure ablaze. After only four days of operation, Pennsylvania Hall burned to the ground as firemen refused to fight the fire and instead focused on protecting neighboring structures.

Over the next four years the city and nation suffered a severe business depression marked by widespread unemployment. Although Philadelphia remained relatively calm, economic, racial, and religious tensions simmered. The political and jurisdiction fragmentation of the city and its surrounding districts did little to deflate or combat those tensions. Increased job competition among ethnic and racial groups, in particular between Irish and Black workers, brought intermittent fighting that exploded into a full-scale riot in August 1842. As a Black temperance society began a parade on August 1 to promote temperance and celebrate Jamaican Emancipation Day, a flag they carried depicting a slave breaking his chains and the rising sun of freedom was misinterpreted and offended white, in particular Irish, bystanders. As the parade reached the public market near Lombard and Sixth Streets, a melee quickly ensued, the parade broke up, and Black marchers were chased throughout the city. By the end of the day a mob torched an abolitionist meeting hall and the Second African Presbyterian Church on St. Mary’s Street. The Lombard Street Riot continued for two more days and caused many Black citizens to flee the city. As the sheriff and deputized citizens attempted to subdue the mob, the predominately Irish rioters turned against them, and public order was only restored after the mayor called out seven militia companies with more than one thousand troops. This clash with law enforcement officials stigmatized the Irish in Philadelphia and set the stage for the next large-scale riots in antebellum Philadelphia.

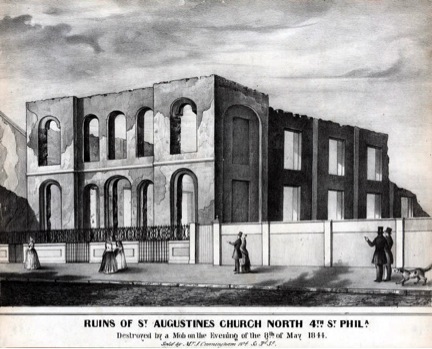

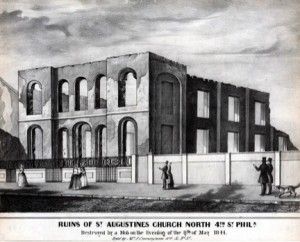

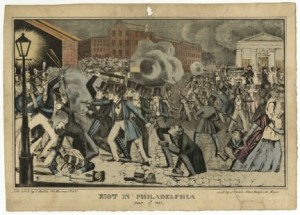

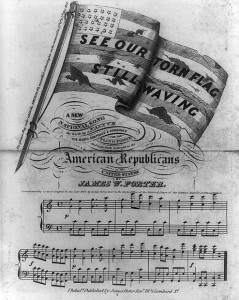

Over the next two years the rise of Nativist and Protestant sentiment combined with the sharp increase in Irish Catholic immigration brought tensions to a fever pitch in the spring of 1844. Beginning as a contest over Catholic resistance to the reading of the Protestant King James Bible in public schools, unrest boiled into the streets in May 1844. On the evening of Friday, May 3, a Nativist organization known as the American Republican Association called for a meeting in the Kensington district that Catholic hecklers swiftly interrupted. The organization called for another meeting in the same area the following Monday and this, too, was disrupted by Irish bystanders. However, this disruption proved more violent as gunshots were exchanged and a riot ensued. Nativists converged on the heavily Irish Kensington district over the next three days and burned more than thirty buildings, including a Catholic school and St. Augustine’s Catholic Church at Fourth and Vine Streets. Order was restored to the area only after the all the county militia companies were called into Kensington.

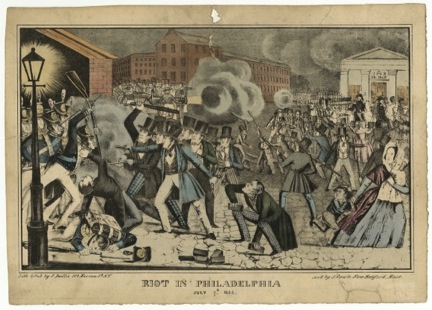

While these actions cooled temperaments in May, they did not bring peace to the city for long. By July anti-Catholic sentiment boiled over again, resulting in the Southwark Riots. On Sunday, July 7, cannons fired by a Nativist mob bombarded militia units protecting a Catholic church. The militia responded with gunfire and fighting between the militia and the crowd continued throughout the day. The rioting stopped the next day as the governor ordered surrounding militia units into Philadelphia to quell the fighting in Southwark.

Explosive and destructive incidents of rioting occurred in multiple urban centers in the United States during the 1830s and 1840s, including Boston, Baltimore, and Philadelphia. While these riots brought destruction and death to Philadelphia, they also produced positive changes. Such violent events fueled discussion about consolidating the twenty-nine jurisdictions of Philadelphia County into the one municipality, patrolled by a unified police force. This political consolidation was completed in 1854 followed by a professional police force in 1855, one of the first modern police forces in the nation. Structural changes such as these helped Philadelphia join several European cities in ushering in the modern city.

Patrick Grubbs is an advanced Ph.D. student at Lehigh University and is writing his dissertation entitled “Bringing Order to the State: How Order Triumphed in Pennsylvania.” He has also been employed at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, since 2009 and has taught Pennsylvania History there since 2011. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University