Trails (Indian)

Essay

In the Philadelphia region prior to European settlement and during the colonial period, the Lenapes and other Indians used their knowledge of the landscape to engineer the most efficient routes through forests, mountains, and often shallow, treacherous waterways. Their complex system of overland paths crisscrossed the region to reach east to the shell fisheries on the Atlantic coast and west into the Wyoming Valley. While Euro-Americans later developed some of these trails into wagon and automobile routes centered on Philadelphia, the Indians’ trails promoted trade and communication with people in many directions within and outside the region.

The Indians who engineered trails took full advantage of the mid-Atlantic landscape to overcome difficult travel conditions. By locating trails above flood levels and along mountain ridges, Lenapes and other natives ensured the routes remained accessible and dry. To avoid excessive ascents through higher elevations, travelers followed trails through mountain gaps or along ridges, such as the stretch of the Great Warriors Path through Greene County, Pennsylvania.

Indian travelers often trekked single-file along relatively narrow paths. Lenape leaders, with a political system based upon autonomous communities, could not command the labor needed to undertake monumental road construction and public works projects like those of the Incas of Peru. The Tulpehocken Path, from Shamokin to Philadelphia, extended only about eighteen inches across in places. Other trails permitted two travelers to walk side-by-side. The European introduction of horses gradually led to widening of many routes.

Along the network of paths, travelers frequently encountered other people, stopped to converse, and shared news of recent events or the fruits of a recent hunt. In wartime, trails could be crowded with warriors, both Indian and European, intent on violence. In peacetime, however, hunters, traders, messengers, diplomats, and those visiting relatives and friends used the paths. Hospitality and fellowship governed life on the trail during such times. Food could be easily found at the many Indian villages and cabins located along the trails or by hunting the abundant game of the forests. Traveling primarily in the spring or fall, voyagers avoided the icy cold of winter and the heat and harassing insects of summer. As darkness approached, those trekking along well-worn trails could typically find overnight accommodations with fellow travelers in shelters built by those who had spent previous nights in the area.

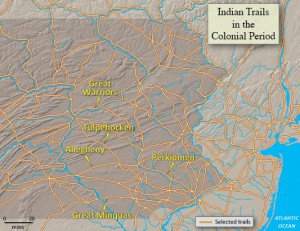

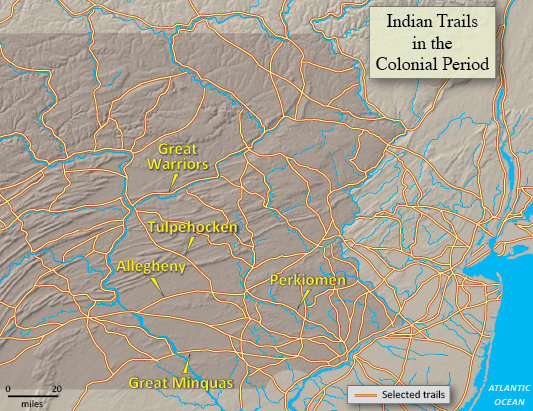

In an extensive study, historian Paul A.W. Wallace (1891-1967) identified 131 distinct Indian trails in Pennsylvania. The Allegheny Path, a primary trail leading out of the Delaware Valley, ran from the future location of Allegheny Avenue in Philadelphia, through Paoli to Harrisburg, across the Susquehanna and into Carlisle, where it forked into the Raystown and Frankstown paths. The Perkiomen Path ran from Philadelphia to Norristown, crossed Perkiomen Creek, and extended into Reading, where it joined the Allegheny Path.

Ironically, the best evidence for Lenape accomplishment in trail-making comes from extensive use of the system by Europeans. Individuals and armies ranging from Moravian John Heckewelder (1743-1823) to diplomat Conrad Weiser (1696-1760) and General John Sullivan (1740-95) used established Indian trails. Perhaps most famously, in 1779 Sullivan marched from Easton along the Great Warriors Path to exact revenge on the Iroquois in New York for their attacks the previous year. Less famously, but likely more importantly, Indian and European traders journeyed along the Great Minquas Path, from the Susquehanna River to the Forks of the Brandywine then to the Philadelphia area, to exchange animal pelts at posts along the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers. This exchange, and thereby this trail, proved vital in giving early Pennsylvania access to the fur trade.

The Lenapes and other Indians plotted courses that accommodated both the landscape and their needs. These trails were not simply carved by hunters following game, but were thoughtfully arrayed routes designed to facilitate travel. Engineered to accommodate people traveling on foot, the trails provided the most efficient routes across difficult terrain. Over time, many evolved into roads and highways, where historical markers recalled the precedents of the Indian trails.

Matthew A. Zimmerman earned his Ph.D. in History at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. He is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of History and Political Science at Middle Georgia State University in Macon, Georgia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University