Industrial Neighborhoods

By Charlene Mires and Jacob Downs

Essay

The growth and decline of industry in the Philadelphia region in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries also shaped the character of many of its neighborhoods. Compact industrial neighborhoods originated at a time when the lack of public transportation made it necessary for workers to live within walking distance of the factories. These row house blocks became home to generations of working-class residents, but as industry declined in the second half of the twentieth century, communities near shuttered factories faced challenges of economic and social dislocation.

The region’s earliest industrial neighborhoods were mill towns near waterways, a location necessary for water-powered factories. For example, Manayunk, which became a neighborhood of Philadelphia with the city’s consolidation in 1854, originated as a textile village along the Schuylkill River in Roxborough Township. Only lightly settled during the early nineteenth century, the area experienced rapid development after 1819, when the Schuylkill Navigation Company completed construction of the Flat Rock Canal and dam. By 1828 the power produced by the new waterfall from canal to river had attracted ten textile mills, which touched off a population and housing boom. The textile industry attracted English, Irish, Scottish, and German immigrants, and a community formed, featuring houses for mill workers and factory owners, churches, schools, expanded mills, and improved roads. By the 1830s the Philadelphia, Germantown, and Norristown Railroad connected the village to Philadelphia. With urbanization, residents of Manayunk—grandly touted as “the Manchester of America”—also experienced problems of the early industrial era, including instability of work, health hazards, and high rates of poverty.

From the early to middle nineteenth century, access to waterways and rail lines dictated the locations of mills and factories, which in turn created or attracted the housing necessary to sustain a workforce. In Kingsessing (later Southwest Philadelphia), for example, the village of Paschalville developed in 1810 near the Passmore Textile Mill on Cobbs Creek. In Kensington, home to mills, factories, and shipyards near the Delaware River, the population more than tripled between 1820 and 1840, from 7,000 to 22,000 residents. In Camden prior to the Civil War, factory owners built housing for workers close to their waterfront mills, sawmills, lumberyards, and railroad companies. Near Camden’s Kaighn’s Point manufacturing district, developer Richard Fetters (1791-1863) built inexpensive houses so enticing that laborers moved across the river from Philadelphia.

Homes in Shadow of Factories

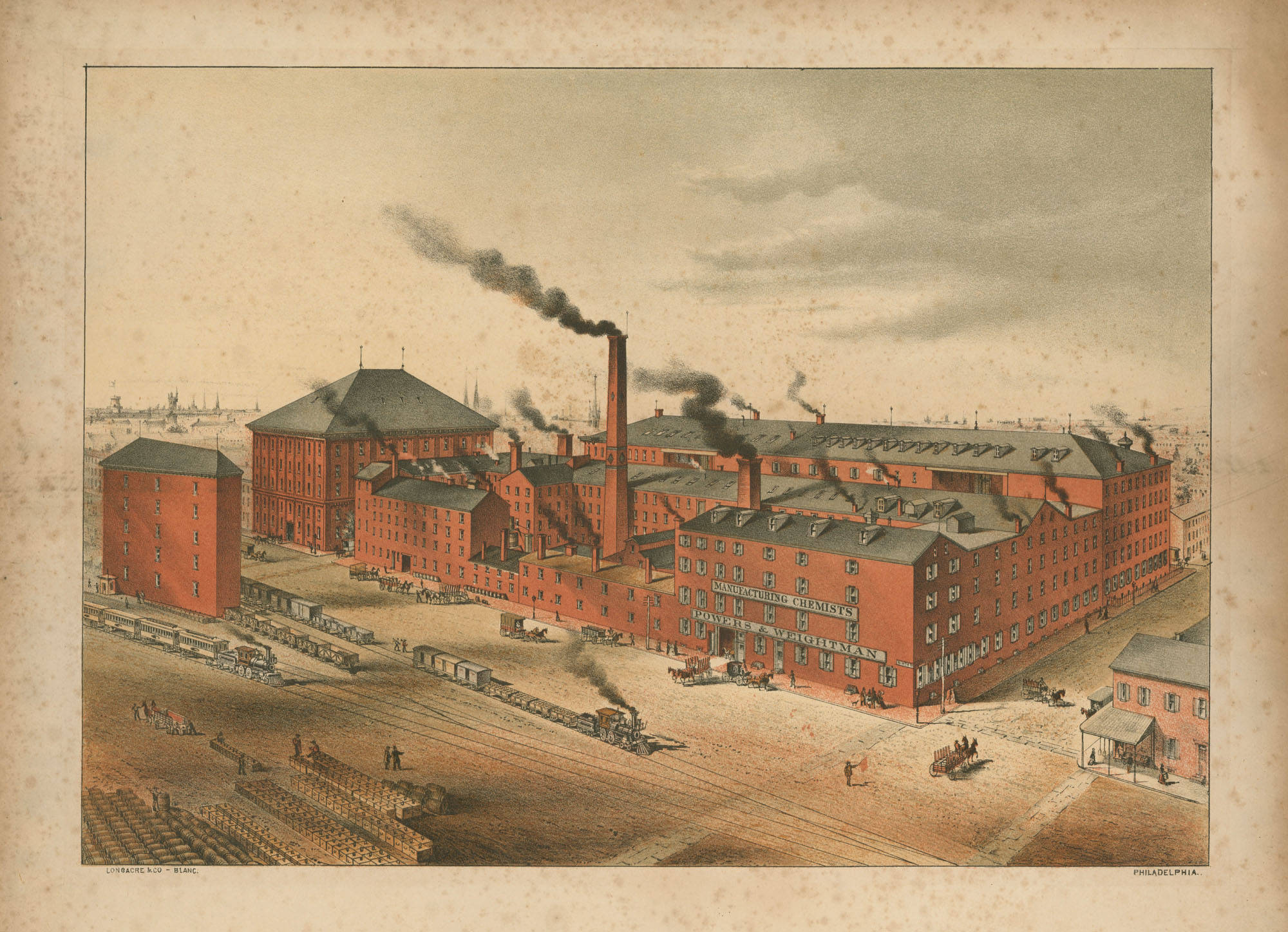

In this era of the “walking city,” before streetcars or subways, industrial workers lived literally in the shadow of the factories. For most, home meant a two-story row house (or a rented room in a row house) on a street lined corner-to-corner with identical homes. The sounds and smells of the factories permeated these neighborhoods. Smokestacks sent pollution into the air, and smoke-belching locomotives shared the streets with horse-drawn vehicles and pedestrians. The rapid growth of industry could easily overwhelm the capacity of the neighborhoods. By 1859, for example, the Manayunk Star and Roxborough Gazette described Manayunk as densely packed with overcrowded and poorly kept houses.

Immigration and ethnicity also shaped life in the industrial neighborhoods. So many English immigrants settled in Kensington in the nineteenth century that it became known as “Little England.” German immigrants found work in the yarn and knitting mills and tanneries of Germantown. The Irish, who represented half of Philadelphia’s nineteenth-century foreign-born population, dominated areas such as Northern Liberties, Fishtown, and Harrowgate and found work in a variety of trades, including textiles. Irish immigrants did much of the bricklaying for the industrial buildings, bridges, and railroads necessary for Philadelphia’s next industrial boom.

An alternative to the typically congested factory neighborhood developed in Northeast Philadelphia when Henry Disston (1819-78) transformed Tacony from a resort spot into a planned industrial community for his saw works and its workers. In the 1870s, Disston purchased a large tract of land in Tacony for a factory to replace his earlier plant in Northern Liberties and for worker housing. In contrast to the row house blocks elsewhere, the town plan for Tacony included lot sizes large enough to accommodate twin homes. Exercising paternalistic control over the district, Disston banned taverns, stables, and steam engines for industries other than the saw works, but he also provided a popular opera house, parks, banks, and a commercial corridor. The small community developed rapidly and gained a favorable reputation. In an 1886 report, the Pennsylvania secretary of Internal Affairs praised Tacony as the ideal manufacturing town.

By the mid-nineteenth century, steam-powered technology dramatically changed the nature and efficiency of industry and produced substantial growth in Philadelphia and other cities. The population of Philadelphia more than doubled from 565,529 in 1860 to 1,293,697 at the turn of the twentieth century as industry grew and intensified across North Philadelphia and in neighborhoods near the Delaware River waterfront. Many workers achieved modest prosperity, often enough to purchase their own homes. Elsewhere in southeastern Pennsylvania, Coatesville’s population expanded by 447 percent between 1850 and 1910, fueled largely by expansion of the powerful Lukens Steel Company. The increase at Chester was even greater, from just over 1,000 residents in 1850 to 20,226 in 1890, an eleven-fold increase produced chiefly by its large shipbuilding industry. In South Jersey, Camden grew nearly as remarkably, from just 9,500 in 1850 to more than 58,000 by 1890 and 75,000 by 1900.

The Streetcar Revolution

During this era of industrial expansion, new forms of public transportation such as the streetcar (introduced in the 1850s and motorized in the 1890s) created the option of moving to less congested, less polluted suburbs for those who could afford the fares, generally five cents each way. The industrial neighborhoods they left behind absorbed a new wave of immigrants who arrived from southern and eastern Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These trends – the departures and arrivals – produced neighborhoods segregated by income, with the poorest and most recent of the new arrivals crowding into areas closest to the factories. With housing in high demand, some of the finer factory-district homes vacated by mill owners or managers became boarding houses. At transit hubs, such as Kensington and Allegheny (K&A) in Philadelphia, business districts developed around banks, taverns, and shops, which served the neighborhoods as well as commuters.

The new immigrant groups changed the industrial neighborhoods and forged new social and cultural networks. They infused the neighborhoods with the cultures and traditions of their homelands, but public transportation also allowed them to connect with others of the same nationality elsewhere in the city. For the large number of Roman Catholics in the latest generation of immigrants, communities were defined not only by industrial geography but also by the boundaries of their parishes. As the Catholic population increased, the spires of new Catholic churches joined the factories as neighborhood landmarks.

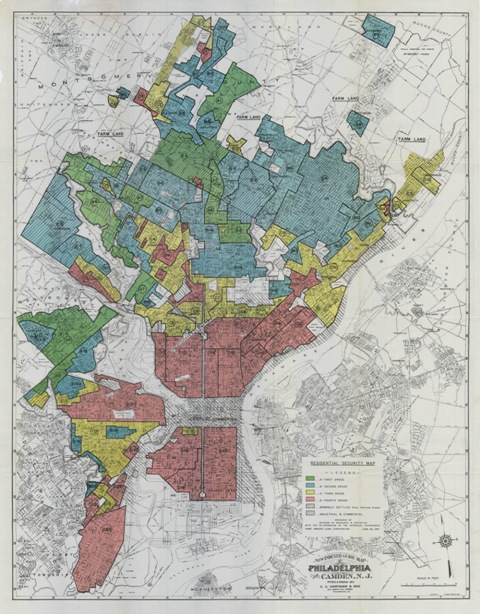

Philadelphia promoted itself as the “City of Homes” as well as the “Workshop of the World,” but over the first half of the twentieth century, the oldest industrial neighborhoods fell into decline. When the federal Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) surveyed Philadelphia in the 1930s, it judged many row house blocks close to factories to be inherently undesirable because of nearby manufacturing, aging housing stock, and presence of immigrants. Color-coded in red and marked with the lowest grade of “D” on maps produced by the HOLC, these areas gained a stigma that discouraged investment and accelerated the deterioration of property even as new generations of residents occupied the homes.

Already challenged, Philadelphia’s industrial neighborhoods experienced a dramatic shift in the second half of the twentieth century when industries closed or left the region, part of a national trend of industrial decline that affected traditional “Rust Belt” cities. While much of the white middle class moved to the suburbs, jobs left the industrial cities, poverty increased, and abandoned factories posed fire risks and offered havens for drug users. Crime and violence increased. In Philadelphia’s industrial neighborhoods, working-class white residents with few resources fought against integration longer than those who had settled the old streetcar suburbs. By the time they left, when they found the means to do so, the African Americans and Latinos who made up the next generation of occupants often found homes dilapidated and lacking in basic amenities. Similar trends occurred in industrial neighborhoods in smaller cities of the region, including Camden, Coatesville, Norristown, and Chester.

Aging Housing & Poverty

By the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, residents in many of the former industrial neighborhoods faced problems such as poverty and limited educational opportunities while inhabiting aging, inadequate housing close to abandoned and hazardous industrial buildings. In many areas, important community institutions such as churches and schools closed or merged as the population declined. At the same time, however, the compact nature of these districts, including their access to public transportation, guided efforts at renewal. With the aid of government programs such as tax credits for adaptive reuse of buildings, some of the former factories gained new life. Other efforts aimed to revitalize the former industrial areas by demolishing abandoned buildings, encouraging new social and commercial investment, and acting to reduce crime.

In Manayunk, revitalization came to Main Street, its primary commercial district. New restaurants moved into abandoned buildings, and businesses once again occupied previously empty storefronts. Developers and business owners promoted the neighborhood and attracted a new wave of residents. Some industrial buildings became apartment complexes and factories, while investors demolished others that could not be converted and replaced with condominium towers for the growing population. In Coatesville, officials embarked on a revitalization project of demolishing abandoned buildings to promote growth and investment. In Camden, attractions such as the New Jersey State Aquarium occupied former industrial sites, and Cooper Hospital and Rutgers University worked toward redeveloping parts of the downtown, although it proved to be a slow process. In Philadelphia, neighborhoods such as Old City and Northern Liberties experienced dramatic redevelopment. Developers adapted old industrial buildings as residences or workspaces or replaced them with new homes and apartments.

In the early twenty-first century, many of the region’s old industrial neighborhoods became just shadows of the vitality of earlier days. But remnants of the industrial neighborhoods remained, undergoing new transitions long after the golden age of industrialization.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and editor-in-chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. Jacob Downs earned a master’s degree in history at Rutgers-Camden. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Boxes & Shampoo: A Callowhill Factory-To-Nightclub Story (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Chester, Pennsylvania: A History of Its Industrial Progress (Archive.org)

- Invincible Cities: Camden

- Kensington Renewal

- Redlining in Philadelphia

- Workshop of the World: Philadelphia

- Zophar, Tran, and the Chocolate Factory (Hidden City Philadelphia)