Sprawl

Essay

Despite Philadelphia’s twenty-first century resurgence as the urban center of a vital multistate region, the city’s revival did not stem the tide of outward expansion in a largely uncontrolled pattern known popularly as “sprawl.” The steepest population growth in the region continued to occur in the newer suburbs and rural locales, in a low-density and heavily auto-dependent form. Regional and community leaders took important steps to slow the pace of that outward growth, but a drop in energy prices and ongoing preferences for suburban living challenged their efforts to curb the land-consuming development, traffic congestion, and social inequalities that are the hallmarks of regional sprawl.

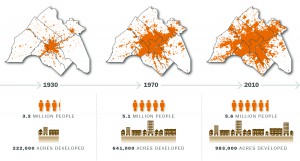

Philadelphia was designed as a compact city, constrained by the Schuylkill River to the west and the Delaware River to the east. The city’s initial expansion beyond those bounds came in the form of clusters of industrial activity and compact neighborhoods, with residents typically walking to the factories where they worked. Although the advent of streetcar and rail lines made longer journeys to work possible, commuting did not begin to become widespread until electric rail and paved roads became more common. But it was widespread automobile ownership, beginning in the 1920s, that fully facilitated “middle-class sprawl” and led to rapidly rising rates of per-capita land consumption.

Although sprawl was relatively limited during the Great Depression and World War II, pent-up demand for housing was met by massive suburban expansion in the postwar era. Fears about neighborhood change, loss of property value, and safety in the wake of the 1960s race-based riots accelerated outmigration as whites fled from many parts of the urban core, not only in Philadelphia, but in other cities in the region, including Trenton and Camden, New Jersey. Widespread auto ownership was a critical enabling factor, but so, too, were federal policies that provided home mortgage subsidies; offered tax deductions for property tax and mortgage interest payments; supported redlining and associated disinvestment in specific core urban areas, particularly minority neighborhoods; and created the interstate highway system, which enabled long-distance commuting by car.

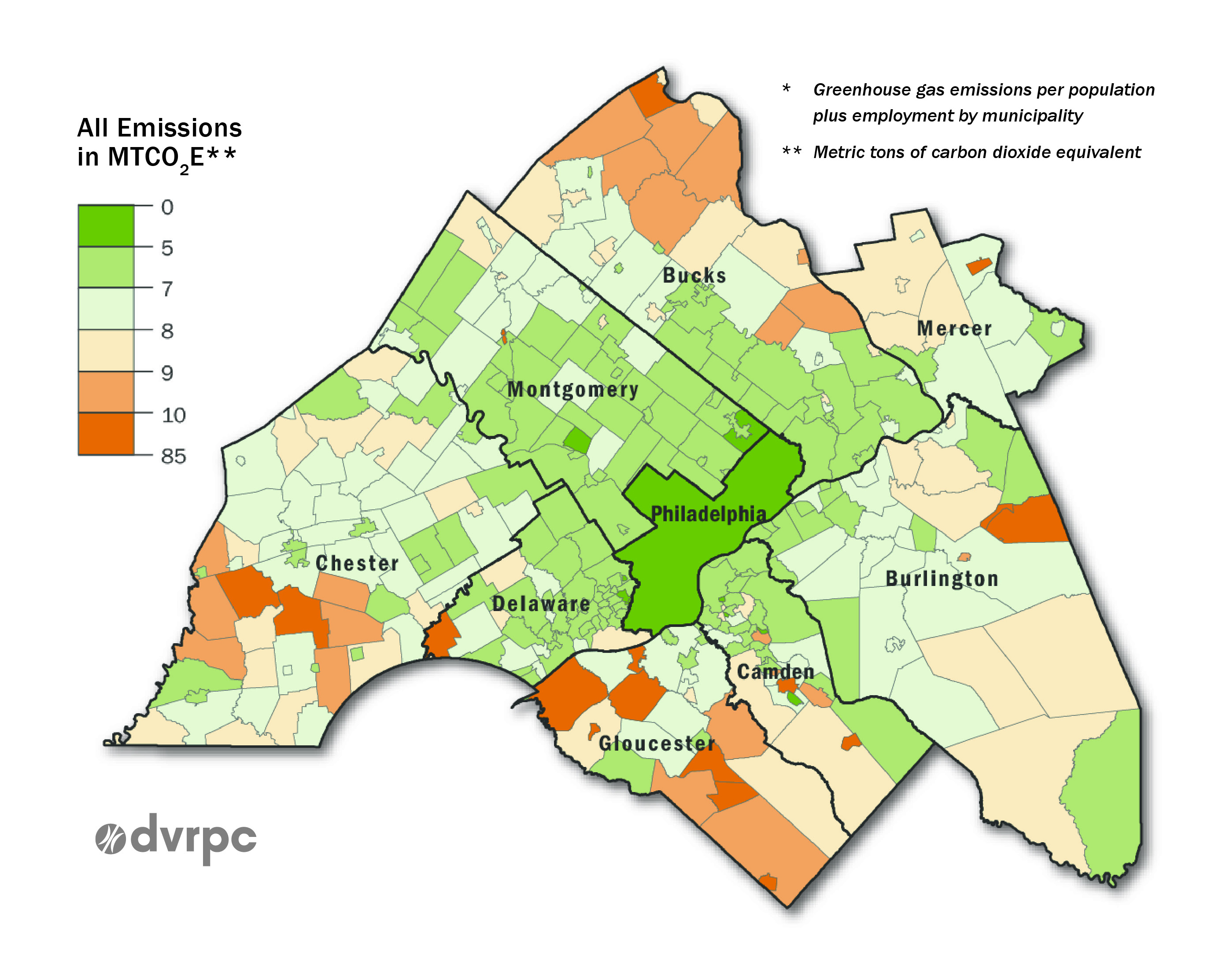

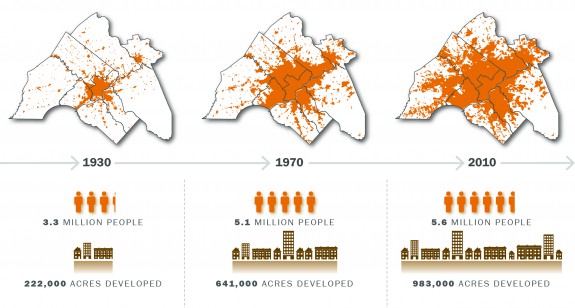

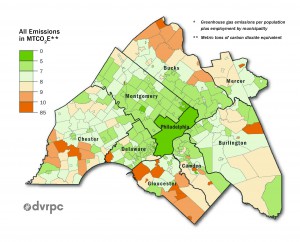

In the immediate postwar period from 1944 to 1954, Philadelphia built up nine square miles of previously undeveloped land, while 61 square miles were developed in the surrounding counties. Over a longer span—between 1930 and 2010—the Philadelphia region’s population increased by 70 percent, yet land consumption more than tripled. The sprawl illustrated by the maps above is distributed unevenly, consisting of large expanses of low-density residential and commercial development that include two Levittowns, one each in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, punctuated as well by more dense suburban centers, including the “edge cities” of King of Prussia and Cherry Hill, each home to a regional mega-mall; pharmaceutical clusters in Mercer County, New Jersey; New Castle County, Delaware; and Montgomery County, Pennsylvania; and office parks in Great Valley, to Philadelphia’s west, and along U.S. Route 1 in Mercer County, New Jersey. These concentrations of commercial and industrial activity helped drive and shape new residential development, leading to dramatic increases in intersuburban commuting. An early example is the proximity of Levittown, Pennsylvania, to the enormous, now largely defunct, U.S. Steel plant that opened in the early 1950s in Fairless Hills. Sprawl has been deliberately limited to a significant extent only in the region’s far eastern reaches, by the federal/state regulatory program that protects ecological resources and manages development in New Jersey’s Pinelands National Reserve.

In 2014, the national coalition Smart Growth America ranked the Philadelphia Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) as thirty-third least sprawled out of 221 metropolitan areas analyzed. This assessment reflected the City of Philadelphia’s denser-than-average pattern of residential development and several centuries of settlement that produced dozens of small towns outside the city, built at fairly high density on old-fashioned street grids. This pattern contrasted quite markedly with the undifferentiated urban sprawl seen in newer regions of the country. At the same time, Philadelphia’s greater-than-average dispersal of employment contributed to growth in traffic congestion associated with reverse and inter-suburban commuting. Ranked by the Brookings Institution as the third most decentralized for job distribution among larger-employment metro regions, greater Philadelphia has 64 percent of all jobs in the region located at a distance of 10 to 35 miles from the central business district.. This decentralized pattern has led some commentators to label the region an “off-ramp economy.”

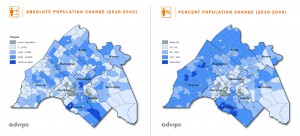

Despite the vaunted growth in the city’s population after 2010—34,291 residents were added between 2010 and 2014—the Philadelphia metropolitan region as a whole lost population during the same period. Indeed, the core urban growth was attributable to high birth rates rather than a net influx of new residents. Nor was Center City densifying in comparison with historical population densities, given that newer households were generally smaller than those of the past and demands for living space per person were rising. Like Philadelphia, four other core cities—Camden and Trenton; Chester, Pennsylvania; and Wilmington, Delaware—all had reached their population peaks in 1950 and mostly have experienced declines since then. Wilmington and Chester did register slight increases between 2010 and 2014. By contrast, the general trend for the counties in the metropolitan statistical area (Philadelphia excepted) was one of mostly robust postwar growth, with more modest growth toward the turn of the millennium and beyond. Much of that growth came in the form of single-family homes and sprawled commercial development. Following a slowdown associated with the national recession that started in 2007, the rate of land development between 2010 and 2014 exceeded that of population growth fivefold—a clear indication that the metro region continued to sprawl.

Countering Sprawl through Regional Collaboration

For a variety of political and perhaps cultural reasons, American metro areas do not embrace the kinds of highly regulatory planning structures that govern land use in many European countries. Few U.S. metros have opted for regional governance, tax-base sharing, growth boundaries, congestion charges, carbon taxes, and other regulatory/redistributive approaches. Instead, policy formation for directing growth lies largely in the hands of local and regional planners, guided by state and federal grants and incentives.

Formed in 1965 and subsequently federally designated as the planning agency for the nine-county greater Philadelphia area, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) creates regional plans, conducts research, and has some control over regional disbursement of federal transportation funds. Yet it does not have direct regulatory power over land use, thus limiting its capacity to guide regional development. New Jersey has a comprehensive state plan, in effect in various incarnations since 1992, that seeks to guide and control development and protect valued natural, agricultural, aesthetic, historic, and recreational resources. But the plan is more aspirational than it is enforceable and regulatory. It provides a blueprint for directing state investments and incentives toward supporting its objectives, but it does not dictate to local governments how they should develop the land within their borders. New Jersey’s Pinelands region, proving the exception, is subject to more direct, enforceable regulation.

The Greater Philadelphia region, as defined by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission, contains over 350 municipalities, each of which is preeminently concerned with its own fiscal health rather than regional economic and environmental sustainability. Regional planning efforts are further challenged by the fact that the municipalities are governed by the differing constitutional and political frameworks of three states: Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. To the extent that municipalities coordinated regionally, they opted for less regulatory, more collaborative programs that more often dealt with the sprawl’s consequences—such as traffic congestion, lack of affordable housing, and loss of open space rather than the root causes of sprawl.

Countering Sprawl by Protecting Open Space

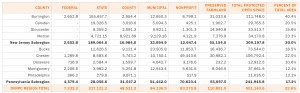

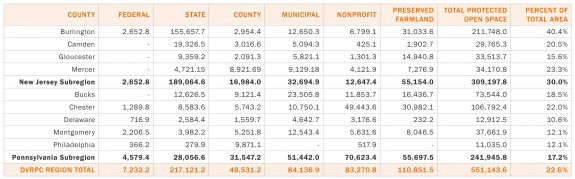

Notwithstanding continued outward development, establishing protected status for open space has proved somewhat successful in preventing sprawl from consuming valued landscapes. As shown in the chart above, by 2015 such protection applied to 23 percent of the DVRPC region, with nearly two thirds of this land in public ownership and one third in private hands. The trend has been toward significant gains in open space, with a 16 percent increase in protected acreage between 2007 and 2011 alone. These protected areas came in the form of traditional state and local parks, forests, and wildlife areas; preserved farmlands; and conservation easements that limit future development of privately owned lands.

Beyond the Pinelands National Reserve, New Jersey has had a long history of land preservation. The Green Acres program, established in 1961 to acquire lands and support agency and nonprofit organizations’ land-protection activities, has been funded to the level of $3.3 billion through a series of voter referendums, none of which has been turned down.

Pennsylvania’s Growing Greener programs provided a total of nearly $2 billion between 2000 and 2012, distributed among state agencies, to support farmland and open-space protection, state park maintenance, watershed restoration, local land-use planning assistance, and other environmental projects. More modest ongoing funding came from a voter-approved waste disposal tipping fee and natural gas extraction impact fees.

Local government ballot measures also provided significant funding for land protection. Between 2008 and 2014, voters approved $141 million of funding for land conservation in Pennsylvania; nearly $2.5 billion in New Jersey (excluding Green Acres statewide ballot questions); and $4.25 million in Delaware (entirely in Newark, which is within the Philadelphia MSA). Nonprofit organizations were also active in protecting lands, through direct purchase as well as acquisition of conservation easements. In this respect, Chester County—one of America’s wealthiest— has had a very active nonprofit land-trust sector that has been quite effective in protecting its valued pastoral and equine landscapes.

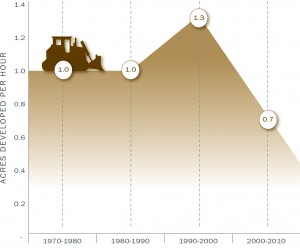

While the rate of land consumption in the DVRPC region did slow significantly between 2000 and 2010 (see chart at right), and land acreage under protection continued to increase substantially, the region nevertheless experienced a net loss of 57,000 acres of agricultural land and 6,500 acres of other undeveloped lands. Between 2005 and 2010, less than half of all new growth took place in areas that DVRPC deemed “appropriate” for growth, such as lands close to existing, more densely developed areas.

Countering Sprawl with Smart Growth

Traditionally, the master plans and ordinances in many of the region’s suburbs have failed to support “smart growth,” that is, the building of communities with dense mixed development in order to concentrate residential construction and protect common areas of open space and critical ecological resources. Post-1990, however, a majority of municipalities in the DVRPC region adopted one or more smart growth measures, such as multi-municipal comprehensive plans, ordinances that support denser suburban development, and transportation plans that encourage alternatives to automobile travel. A limited amount of new, greenfield development adopted conservation design principles. For example, the Hankin Group garnered considerable acclaim for its Eagleview development in Chester County. In 2003, the regionally headquartered megadeveloper Toll Brothers created a “Toll Brothers City Living” division, devoted to building suburban communities with something of a townlike feel. Smart growth and related measures are politically palatable alternatives to straightforward imposition of stringent land-use regulations, since they accept and promote economic, residential, and commercial growth, while at the same time seeking to direct it in ways that protect open space, preserve farmland, reduce traffic congestion, and improve regional “livability” generally.

Controlling Sprawl through Transportation

Historically, regional highway development has divided communities, displaced residents, and facilitated sprawl. More recent transportation planning, however, transitioned toward managing and limiting sprawl, rather than promoting it. The “post-interstate” era is represented by such projects as the long overdue interchange linking I-95 with the Pennsylvania Turnpike and the widening of portions of several existing expressways. Many of the post-interstate projects have been accompanied by walkways, bicycle paths, and “traffic-calming” design features.

Transit-oriented development (TOD), which has been encouraged and incentivized by state governments, can counter sprawl by concentrating development around transit stations and promoting commuting by public transportation. DVRPC listed, in 2015, 154 ”development near transit” projects, the vast majority of them in the city of Philadelphia, at a wide range of scales and in various states of proposal or completion. One of the city’s success stories is Paseo Verde, a development completed in late 2013 that provides affordable LEED-certified housing, a mix of retail and community service enterprises, and access to all SEPTA regional rail trains at the Temple University rail station, next to which it is situated. Yet TOD projects can be difficult to implement. Despite consistent state-level support for TOD at Mercer County’s Princeton Junction train station, authorities struggled unsuccessfully for years to develop a plan to replace its acres of surface parking with parking garages and mixed-use development in a way that would be acceptable to residents of surrounding neighborhoods.

Both road and public transit received a significant funding boost in Pennsylvania in the form of Act 89 late in 2013. For the portion of Pennsylvania covered by the DVRPC this amounted to $11 billion in funding through 2040, mainly to support road and rail improvements and expansion, with funds also supporting bicycle and pedestrian trails. Even with Act 89 in place, Pennsylvania remained considerably more underfunded with respect to regional needs than the state of New Jersey, according to DVRPC assessments. Moreover, federal transportation funding, which historically provided more than 50 percent of regional transportation funding, remained mired in uncertainty and delay in the early part of the new millennium.

Public transit ridership increased regionally after the turn of the millennium. Long-term improvements to rail and bus service could be expected to help alleviate traffic congestion, but it could not be presumed that they would automatically reduce sprawl. Ironically, easier access to parts of the region may foster further sprawl; much will depend on regional and local planning efforts, economic conditions, and general demographic trends.

Sprawl and Equity Considerations

The Philadelphia region has been characterized by marked inequalities associated with income, race, and opportunity. Indeed, a 2015 analysis conducted by the Martin Prosperity Institute found that Philadelphia was one of America’s more highly segregated large metro areas, by income, education, and employment. “Employment sprawl”—the outward spread of jobs to suburban office parks, retail malls, health complexes, and other job centers—dramatically lengthened commutes for many entry-level workers living in the affordable neighborhoods of Philadelphia. While the Martin report did not absolutely prove causality, it did emphasize the relationship between average length of public-transit commutes and segregation.

Smart growth is not necessarily a solution to social and spatial inequalities. Even though the smart growth agenda supports urban redevelopment and regional equity, suburban locales frequently employ smart growth and other growth management rhetoric to preclude most new developments, especially higher density development that could provide affordable housing. Even when higher-density developments are built, they usually offer little in the way of low-income housing options, and most residents do not hold jobs within these communities.

In response to these concerns, several grass-roots regional equity coalitions have brought together stakeholders from government, labor, business, faith-based organizations, and other places to address these issues. In 2005, a regional equity summit was held in Philadelphia, and equity issues have been on the agenda of the Philadelphia Metropolitan Caucus. Such initiatives—while doing laudable service by bringing attention to equity issues—have hardly been equipped to reckon with the deep structural factors, at multiple scales, that gave rise to those inequalities.

Looking Ahead

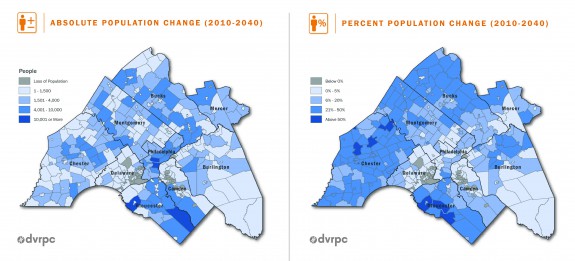

DVRPC forecasts continued robust growth through 2040 in the areas already growing most rapidly—Chester County, Pennsylvania, and Gloucester County, New Jersey—and in lesser measure in Bucks and Montgomery Counties in Pennsylvania. Continued growth is also likely in New Castle County, Delaware. The city/county of Philadelphia is expected to continue growing, with a total population increase of 6.9 percent over 2010, but since the suburbs will also continue to grow, the city’s share of the region’s population is forecast to decline from 27 to 26 percent.

Many factors—difficult to predict—will help determine how that growing population gets distributed across the region’s land base. These include energy markets and prices, concentrations of employment opportunities, the extent to which young people continue to favor urban living, and immigration trends. Another trend that is pushing sprawl even beyond the current boundaries of the region is the development of second homes in the Poconos region and along the New Jersey shore, driven in considerable part by people whose first homes are in the Philadelphia area. Moreover, Philadelphia has become something of a “sixth borough” for New York City, with 8,000 people commuting from Center City alone. Additional New York City commuters, living in a less dense, more sprawled fashion than their Center City counterparts, are to be found in Bucks and Mercer Counties. And there is increased commuting into the region, notably from Lancaster County, to Philadelphia’s west, where the additional demand for housing has exacerbated the already extreme pressure on the area’s rich agricultural lands.

National, state, and local studies have blamed urban sprawl for a laundry list of maladies, among them wasteful government spending, inefficient energy consumption, high per-capita greenhouse gas emissions, traffic congestion, loss of prime farmland and open space, air and water pollution, excessive water demands, declining social capital, obesity, shortened life expectancy, and a host of social and environmental injustices. Yet at the same time, sprawled development patterns have provided desirable residential choices to people able to make such choices. That makes managing sprawl an immense challenge, especially given the reluctance to consider carbon taxes, higher gasoline taxes or vehicle-miles-traveled charges, congestion charges, adjustments to the tax deductibility of home mortgages and property taxes, or stringent land-use regulatory measures. Greater Philadelphians—like many Americans—are conflicted about sprawl and what to do about it, leading some frustrated planners to declare that while Americans hate sprawl, they also hate density.

Robert J. Mason is a professor in the Department of Geography & Urban Studies at Temple University, with interests in land use, environmental policy and planning, watershed management, and hazards in North America and East Asia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission's "Connections 2040" Plan for Greater Philadelphia

- Chester County Planning Commission's "Landscapes 2: Bringing Growth and Preservation Together for Chester County"

- New Jersey Department of State's "State Plan"

- New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Green Acres Program

- Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection "Growing Greener"

- Smart Growth America "Measuring Sprawl 2014"

- Postwar Rise of the Suburbs Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)