British Occupation of Philadelphia

Essay

On September 26, 1777, the British army marched into Philadelphia, beginning an occupation that lasted until the following spring. Its arrival led patriots to flee and Loyalists to rejoice, although wartime shortages soon led to suffering for those who remained in the city. The occupation, however, led to no concrete gains, and the British abandoned the city the following June.

The occupation of Philadelphia deviated from a British plan to conquer New England in 1777, after two years of inconclusive war. To conquer New England, the British intended to send two armies into New York state. The first, headed by General John Burgoyne (1722-92), proceeded south from Canada. At the same time, forces led by General William Howe (1729-1814) would have headed north from New York City along the Hudson River. These two armies would have divided New England from the other colonies, allowing the British to invade and conquer.

Howe, to the surprise of his superiors, did not follow through on this plan. Whether from personal dislike of Burgoyne, fear of allowing General George Washington (1732-99) time to rebuild his army, or doubts about his own ability to prosecute the Hudson River campaign, he rejected the plan. Instead, with a force of about fifteen thousand English and German soldiers, he sailed south along the coast and then headed up the Chesapeake Bay toward Philadelphia. In August 1777, he landed at Head of Elk, some fifty miles from the city.

Howe set his sights on Philadelphia for a number of reasons. Philadelphia, of course, was the American capital and the meeting place of the Continental Congress. Howe also apparently hoped to draw Washington into a battle that might destroy the Continental Army once and for all. Furthermore, prominent Loyalists, including Joseph Galloway (1731-1803), had claimed that more than 75 percent of Americans in Philadelphia and the surrounding region were loyal to the crown and would welcome and aid the British.

Battle of Brandywine Creek

Washington, watching Howe’s movements carefully, attempted unsuccessfully to stop the British advance at the Battle of Brandywine Creek (September 1777). It was a costly loss–Washington suffered some nine hundred casualties (of eleven thousand soldiers), while Howe lost only 550. As the British army approached Philadelphia, thousands of patriot citizens fled, including the delegates to the Continental Congress. Sarah Logan Fisher (1751-96), the wife of a prominent Philadelphia merchant, described “wagons rattling, horses galloping, women running, children crying, delegates flying, & altogether the greatest consternation, fright & terror that can be imagined.” One estimate suggests that more than 10 percent of Philadelphia’s homes were abandoned by their owners before the British arrived, and reports of looting and theft grew. When Howe entered Philadelphia on September 26, 1777, Loyalists lined the streets to welcome the return of British authority. On October 5, Washington tried to dislodge the British at the Battle of Germantown, but this effort also failed.

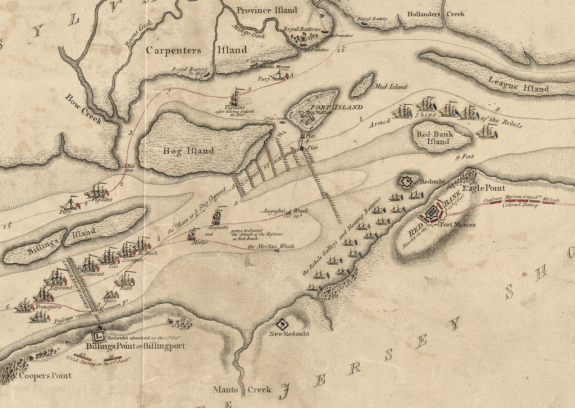

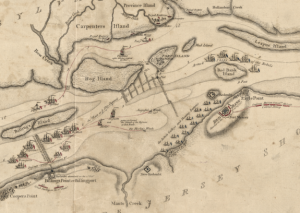

Once in control of Philadelphia, Howe faced serious problems. Even though thousands of Americans had fled, the civilian population still numbered some fifteen thousand. Howe’s forces added another fifteen thousand. But Howe’s supply lines were inadequate. Having marched overland to Philadelphia, he needed to control the Delaware River to ensure an adequate supply of provisions. The Delaware, however, was guarded by two American forts, Fort Mifflin on Mud Island and Fort Mercer on the New Jersey side of the river. The Americans successfully defended both forts for almost seven weeks. Suffering followed in Philadelphia, as food and other provisions were in short supply. British officers quartered with local citizens, churches became hospitals for sick and wounded soldiers, and Philadelphians described British and German soldiers stealing horses, cattle, wood, food, and clothing. The suffering of American prisoners in the Walnut Street Jail was especially severe, as prisoners endured hunger, cold, and abuse from their jailers. In October 1777, the Quaker diarist Elizabeth Drinker (1735-1807) described the suffering of the city, writing “if things dont change ‘eer long, we shall be in poor plight, everything scarce and dear, and nothing suffer’d to be brought in to us.” The forts fell in November, relieving the blockade, but prices in the city remained high and citizens continued to complain of theft and other crimes committed by soldiers. Howe tried, without much success, to deter such behavior. He offered monetary rewards for information about crimes, and frequent courts-martial sentenced men to up to a thousand lashes for plundering and other crimes.

During the long fall and winter months, the British built up the city’s defenses, kept an eye on the American army at Valley Forge, and sent foragers into the countryside to search for wood and hay. But such tasks could not occupy the thousands of men in the army, and the British also turned to a wide variety of leisure activities. Some occupied themselves by playing cards, drinking, gambling, and visiting prostitutes. Others sought more elaborate entertainments, arranging dinner parties and taking part in amateur dramatics. British officers put on plays at the Southwark Theatre on Monday nights from January to May, performing at least fourteen different plays.

Howe’s Resignation

When Howe resigned in April 1778, his officers planned a grand celebration to honor him before his departure. This “Meschianza” (in Italian, “medley”) began with elaborately decorated flatboats and galleys carrying officers and hundreds of guests down the river. This procession was followed by a tournament in which British officers dressed as medieval knights jousted in honor of the “Ladies of the Blended Rose” and the “Ladies of the Burning Mountain.” The tournament was followed by a feast, fireworks, and dancing. Participants judged the event a stunning success, but not all Philadelphia citizens agreed. The Meschianza cost more than three thousand guineas, a stunning amount of money in an occupied city where citizens complained regularly of shortages and high prices. The diarist Drinker criticized the officers’ extravagance, writing, “How insensible do these people appear, while our Land is so greatly desolated, and Death and sore destruction has overtaken and impends over so many.”

While Howe and his army spent the winter in Philadelphia, the fortunes of war were turning. On October 17, 1777, Burgoyne (lacking support from Howe) surrendered at Saratoga. This American victory encouraged the French to make an alliance with the Americans. With British plans in America threatened by the French fleet, the British could no longer afford to occupy Philadelphia, especially as they had gained nothing from being there. General Henry Clinton (1730?-95) was ordered to abandon Philadelphia and retreat to New York. The British army left Philadelphia in June 1778, accompanied by some three thousand loyalists.

The British occupation and abandonment of Philadelphia also led to difficult choices for Black residents of the city, both free and enslaved. In 1777 and 1778, it was not clear whether an American or a British victory would be more likely to lead to freedom and greater rights. On the one hand, Quaker and abolitionist sentiment in Philadelphia had been growing in the decade before the war. As masters freed their slaves, the free Black population of the city grew. Slaves in Philadelphia might have hoped that an American victory would lead to yet more manumissions, or even the outlawing of slavery. During the war, thirty-five Black men served in the Second Pennsylvania Brigade of the Continental Army, and others served on American privateers. On the other hand, Black men and women in Philadelphia quickly learned of Lord Dunmore’s Proclamation (November 7, 1775) offering freedom to patriots’ slaves who joined the British forces. Although Dunmore was the royal governor of Virginia, news of his proclamation reached Philadelphia within a week. During the occupation, many Africans and African Americans seem to have decided that the British offered better prospects than the Americans, and served among them as soldiers, guides, and laborers. When the British evacuated, dozens of slaves fled with them.

The occupation of Philadelphia did little for the British war effort. The American government survived, as the Continental Congress fled the city. Washington’s army survived the harsh winter at Valley Forge. Relations between the British and Loyalists in Pennsylvania worsened. Worse, Howe had lost a vital opportunity. By failing to meet Burgoyne in New York, he had thrown away the best chance the British would have to conquer New England.

Martha K. Robinson is an Associate Professor of History at Clarion University of Pennsylvania. Her publications include “New Worlds, New Medicines: Indian Remedies and English Medicine in Early America,” Early American Studies 3 (Spring 2005): 94-110. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- The Storm: 1765-1790 (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- Occupation of Philadelphia (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Major John Andre (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- A Special Relationship: Philadelphia and Great Britain (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Art in Revolutionary Philadelphia (Philadelphia Museum of Art)

- The Historic American Revolution Trail of Greater Philadelphia (Visit Philadelphia)