Subway Concourses

Essay

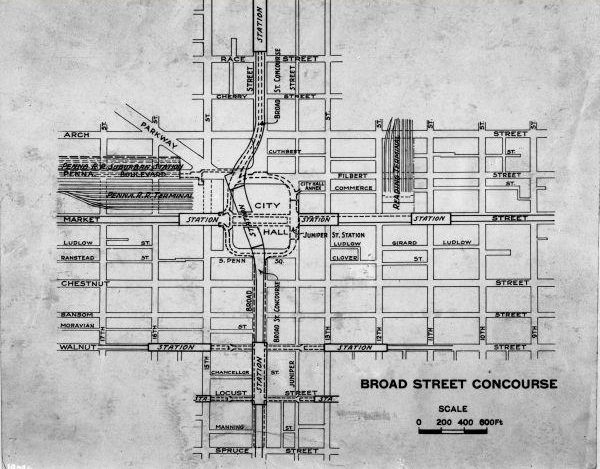

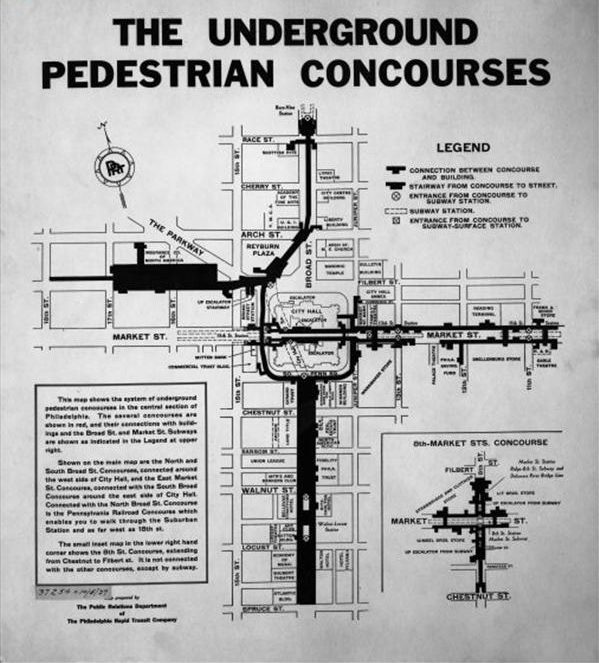

Originally built by the Philadelphia Transit Company in the early twentieth century, the underground concourses in Center City Philadelphia played a crucial part in the construction of subway tunnels and then expanded into a network of private and publicly owned pedestrian walkways and storage facilities. In 1912, the City of Philadelphia assumed active development of the system in the first of many transitions of ownership. Over time, the system stretched to three and a half miles of tunnels and hidden hallways from Eighth to Eighteenth Streets and from South Street to Walnut and Locust Streets. Including shops, entrances to buildings above, and even a division of law enforcement, the underground concourse system provided transportation and development opportunities for Philadelphia.

The underground concourse dates to 1924, but the labyrinth began as part of the construction of the subway system, not as a way for pedestrians to avoid bad weather. To build the subway, workers used picks and shovels to dig trenches, which were then filled with a tunnel and re-covered. To move materials and equipment, they also created parallel walkways at an estimated cost of $10 million. These walkways became the concourses, with the first pedestrian portion completed in 1927 between the Race-Vine Subway Station and a station then at Filbert Street. Further expansions were completed in 1930 with the opening of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s (PRR) Suburban Station—then known as Broad Street Suburban Station. The concourses provided entrances to businesses above ground, such as Wanamaker’s department store and Girard Trust. Other businesses opened below ground, including the Bellevue-Stratford Hotel’s coffee shop in 1927 and several Art Deco-style barbershops.

The concourse slipped into obscurity as confusing signage, lack of light, and general disrepair kept pedestrians above ground. In 1948, however, the city decided to invest in its underground infrastructure and installed over a mile of new tile and illuminated signage to replace the earlier vague, wooden signs. By the 1950s, the executive director of the Philadelphia Planning Commission, Edmund Bacon (1910-2005), proposed a radical expansion including an underground shopping area with covered areas as well as open-air green spaces. This plan, part of the proposed new Penn Center west of City Hall, became hotly debated among city planners because of its expense. Eventually, under pressure from city government, the PRR offered funds to guarantee construction of the shopping concourse below Penn Center. From the onset, however, the underground shopping center failed to meet expectations and struggled financially.

Another opportunity to expand the concourse system emerged with the 1958 proposal by Mayor Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974), Bacon, and R. Damon Childs (1929-98) to build a commuter rail tunnel to connect Suburban Station with the Reading Company’s Reading Terminal. As part of the redevelopment of Market East, the tunnel expansion, with included concourses, was intended to draw suburban middle class visitors into a vast system of retail stores below. The commuter tunnel did not open until 1984, more than twenty-five years after initially proposed, but in the meantime the multilevel Gallery I shopping mall opened on East Market Street in 1977, providing valuable new space for the vendors who occupied the network of underground walkways. When the commuter tunnel finally opened, its accompanying underground walkways connected the Gallery with the earlier segment of concourse around Penn Center and Suburban Station.

During the prolonged debates about the commuter tunnel, the concourse system passed from the Philadelphia Transit Company to the City in 1968, when the newly formed Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) could not afford to purchase the vast subterranean system from the PTC. The deal excluded Suburban Station and privately-owned shops below Penn Center. In 1969, following a series of crime-related incidents in the subways and concourses, the Philadelphia Police Department commissioned a special subway unit known as the Philadelphia Transit Unit (later renamed the Concourse Unit), which continued even after SEPTA formed its own transit police unit in 1981. In all, the work between the Transit Unit and SEPTA’s own officers decreased major crime in the underground labyrinth by 50 percent by 1985.

Much of the concourse fell into disrepair between 1980 and 2014, and many segments closed. Some sections never opened to the public because of private ownership or lack of funds. Pedestrians who associated the concourse system with crime preferred to stay above ground. However, in 2014 SEPTA leased the concourse system from the City for thirty years. In an effort to revitalize the concourses, SEPTA launched the Center City Concourse Improvement Program, a $68.2 million plan to reenergize the empty concourses along Broad and Market Streets by 2021 with infrastructure upgrades, interactive transit signage, new storefronts, and creative place-making such as public artwork, farmers markets, and special events.

The first of four phases of the Concourse Improvement Program began in 2015 with the replacement of escalators at Eighth Street and Fifteenth Street as well as the elevator connecting Eighth Street Station to street level. Plans for concourse improvements called for 20,000 square feet to be updated, reconfigured, and repaired. Connections with the concourse also were included in plans for the Comcast Technology Center on Arch Street. The work continued the subway concourses’ long history of tracking Philadelphia’s undulating waves of urban decay and revitalization in the city core.

Samantha Smyth studies history at Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University