Turnpikes

Essay

From their earliest introduction in Pennsylvania in the late eighteenth century to their modern incarnations as high-speed highways, turnpikes have expanded Philadelphia’s reach to points west and linked the region with other commercial centers and suburbs of the eastern seaboard. Beginning with the first turnpike in the United States, a sixty-two-mile paved toll road from Philadelphia to Lancaster completed in 1795, private investment authorized by state governments enabled swift and extensive construction of improved roads to meet the needs of changing times. The first generation of turnpikes, completed by the 1820s, gave the Philadelphia region connections reaching as far west as Ohio, north through New Jersey to New York, and south through Delaware to Baltimore. In the automobile age of the twentieth century, when states again embraced toll roads as a way of financing high-speed, limited-access superhighways, the Pennsylvania and New Jersey turnpikes cut through Philadelphia’s suburbs and embedded the region in the interstate highway system.

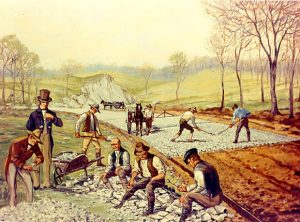

Turnpikes take their name from the pole or pike used to block entrance to a road until a toll is paid. First introduced as a means of road improvement in England in the late seventeenth century, turnpikes emerged in the United States in the decades after the American Revolution. The need to improve the new nation’s rudimentary and haphazard dirt roads, many of them created by foot traffic over former Indian trails, far exceeded local capabilities or public finances. Seeking a solution, state legislatures awarded charters of incorporation for turnpike companies and empowered them to sell stock and collect tolls in exchange for improving or creating roads for faster and easier travel. With state economies highly dependent on moving agricultural goods to market and with populations spreading westward, legislatures readily granted charters to hundreds of turnpike companies. Within a few decades, by the 1830s, the nation had almost twelve thousand miles of turnpikes.

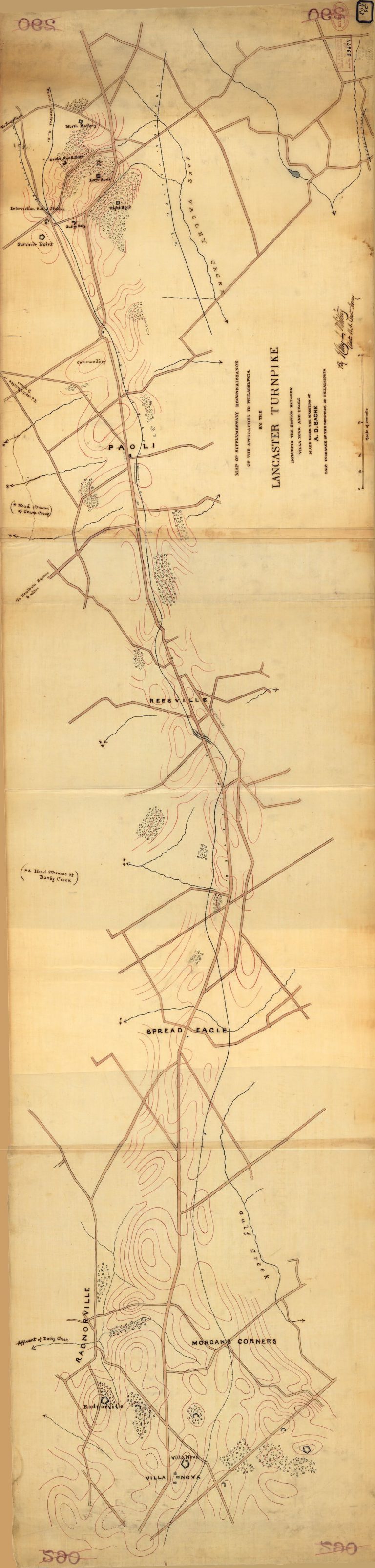

Pennsylvania inspired the wave of toll road construction with the success of the Lancaster Turnpike, which mostly followed the Philadelphia-Lancaster Road that had been in use throughout the eighteenth century. The earlier road, in addition to serving as the link between Philadelphia and Lancaster (founded in 1729), was the “Great Wagon Road” that enabled migrants and freight to move west across southeastern Pennsylvania and from there into the backcountry of Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina. Discussion of improving the heavily traveled road began among merchants and state legislators shortly after the War for Independence and, with lobbying by Philadelphia elites, came to fruition with a charter of incorporation for a turnpike company in 1792. Residents in and around Lancaster and Philadelphia eagerly bought one thousand shares of stock, valued at $300 each, and the company organized under the leadership of William Bingham (1752-1804), a Federalist political leader and prominent Philadelphia merchant.

Paved With Stone

By 1795, the completed turnpike to Lancaster required tolls but it had been paved with layers of crushed stone, widened and straightened, and engineered for good drainage. Inns and taverns opened along the route— purportedly as many as one per mile— to serve an increasing volume of traffic. A sturdy stone bridge carried the road across Brandywine River in Downingtown; by 1805, a separately chartered toll bridge (the “Permanent Bridge”) carried Philadelphia traffic to the turnpike over the Schuylkill River at High (Market) Street. Although some objected to paying to use the road and its bridges, the faster travel time to market made the tolls worthwhile for farmers, and the reliability of the road benefited freight haulers and stagecoach operators. The project produced steady if not spectacular dividends for investors.

The Lancaster Turnpike inspired a nationwide rush of turnpike-building and rivalries among cities. As toll roads radiated outward not only from Philadelphia but also from New York, Wilmington, and Baltimore, they knit together a region that later travelers would recognize as the Northeast Corridor. The important connection between the commercial hubs of Philadelphia and New York received attention from turnpike projects extending from both cities. For example, the Frankford and Bristol Turnpike (chartered 1803) carried traffic through Bucks County to the Delaware River at Morrisville, where a ferry crossing allowed connection with turnpikes across New Jersey to New York. (Until the 1850s, most turnpike activity in New Jersey emanated from New York investors eager to bolster New York-Philadelphia commerce or improve connections with agricultural areas in northeast Pennsylvania.) To the south, the Philadelphia, Brandywine, and New London Turnpike Company chartered by Pennsylvania in 1808 and Delaware’s Philadelphia Pike, built across the northern neck of the state between 1813 and 1823, enabled travel and trade between Philadelphia and Baltimore.

Toll roads reached out from Philadelphia like spokes of a wheel, connecting the city to the interior of Pennsylvania. Turnpike companies improved the northwesterly Germantown and Ridge Roads through Philadelphia County, and then the Germantown and Perkiomen Turnpike (opened in 1799) extended travel for an additional twenty-six miles to Reading. Turnpikes also strengthened Philadelphia’s connections to the Lehigh Valley via Bethlehem Pike (chartered in 1804). Where turnpikes reached into the agricultural countryside of southern Chester County, they met with similar roads extending northward from Wilmington, Delaware. Across the expanse of Pennsylvania, helped by state funding for turnpikes beginning in 1806, a proliferation of short turnpikes between communities created the means for people and products to travel between Philadelphia and any corner of the state, then west into Ohio.

Regional Turnpike Network Expands

By the 1820s, turnpikes had vastly expanded Philadelphia’s regional connections by improved (often paved) roads. Enthusiasm for turnpikes waned, however, with the advent of canals and railroads and the realization that most turnpikes returned meager long-term profits. During the 1850s, South Jersey gained the Black Horse and White Horse Pikes as improvements to earlier roads, and Pennsylvania chartered turnpikes between Philadelphia and West Chester (1848), between Darby and Ridley in Delaware County (1851), and near Philadelphia along the Wissahickon Creek (1856). But most turnpike development at mid-century focused on shorter wooden-plank roads connecting with the railroads and canals. By the end of the nineteenth century, most turnpikes reverted to public use as the charters for turnpike companies ended or as the companies surrendered them for lack of profit. An era of turnpikes ended, but the states gained an extensive network of public roads made possible by private investment. Over time, the nineteenth-century turnpikes became state and U.S. highways.

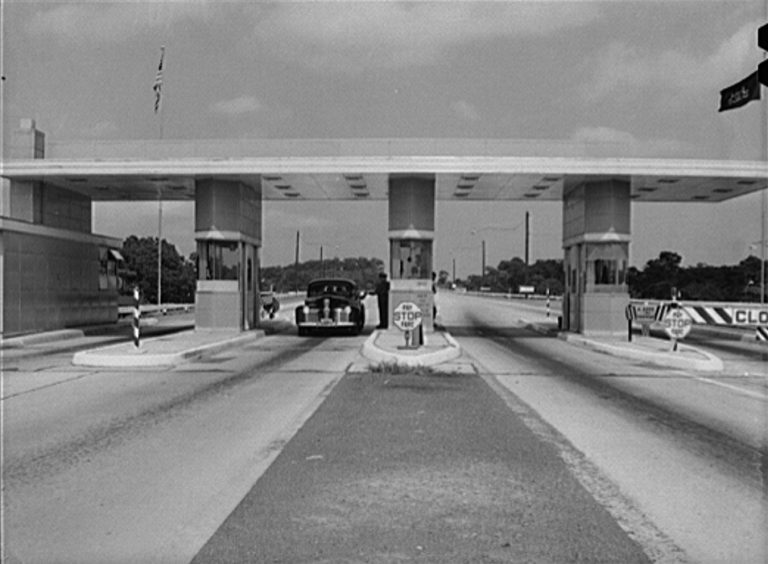

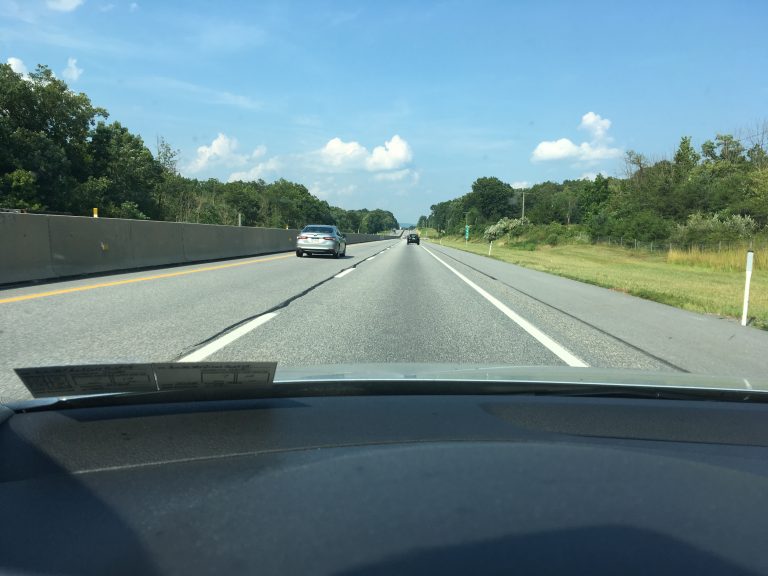

As a method for financing transformational roadways, turnpikes revived in the twentieth century to meet the demands of the automobile age. The new generation of toll roads in Pennsylvania and New Jersey blazed multilane, limited-access superhighways across long distances, not radiating outward from cities but skirting their suburban fringes. The outlying interchanges for Philadelphia on the Pennsylvania and New Jersey turnpikes still positioned the city within the emerging Northeast Corridor and connected it to the West, but vehicles also could speed by Philadelphia en route to other destinations. Turnpike service plazas, offering gasoline, restaurants, and restrooms, encouraged drivers to stay on the highway.

The Pennsylvania Turnpike, begun during the Great Depression of the 1930s, aimed to produce jobs as well as an improved highway across the state. Its first phase (opened in 1940) ran through central Pennsylvania between Harrisburg and Pittsburgh, a route that allowed its builders to take advantage of a roadbed and mountain tunnels that had been abandoned by a nineteenth-century railroad venture. When the turnpike extended to the Philadelphia area in 1950, its interchange twenty miles west of the city near Valley Forge set the stage for a rush of industrial, commercial, and residential development. The growth of an “edge city” at the former village of King of Prussia gained further impetus from completion of the turnpike’s Northeast Extension toward New Jersey and Scranton between 1954 and 1957 and the Schuylkill Expressway connection with Philadelphia in 1958. The turnpike’s exits at Plymouth Meeting, Whitemarsh, and Willow Grove also attracted commercial development to Philadelphia’s suburbs.

New Jersey Turnpike

The New Jersey Turnpike, authorized in 1948 and opened in segments during 1951-52, solidified the state’s position as a vital East Coast transportation corridor by funneling nonstop traffic on a nearly straight diagonal from rural South Jersey (where the Delaware Memorial Bridge replaced ferry service across the Delaware River in 1951) to the George Washington Bridge into Manhattan. As the interstate highway system developed during the 1950s and 1960s, the turnpike offered an alternative to the partially completed Interstate 95 between that highway’s segments in Delaware (the Delaware Turnpike) and New York, thus speeding trips between Washington, D.C., and Boston. The turnpike’s exit closest to Philadelphia, in largely agricultural Mount Laurel Township, Burlington County, spurred plans for development resembling King of Prussia in Pennsylvania—industrial parks, shopping centers, and suburban subdivisions. In Mount Laurel, however, these proposals threatened displacement of longtime African American residents, who viewed the township’s development strategy as an attempt to cultivate a more white, middle class population. Their effort to build low-cost garden apartments for displaced residents led to two far-reaching court decisions (1975 and 1983) banning exclusionary zoning and defining the responsibilities of communities to provide affordable housing.

For the new generation of automobile turnpikes, Pennsylvania and New Jersey created independent agencies with authority to raise revenue, build the roads, and manage the enterprises: the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission and the New Jersey Turnpike Authority. (In Delaware, the state Department of Transportation held jurisdiction over the tolled segment of I-95.) The Pennsylvania Turnpike, a risky proposition during the Great Depression, began construction with a $29 million grant from the federal Public Works Administration and sold its first $41 million in revenue bonds to the federal Reconstruction Finance Corporation, which in turn sold them to private investors. The New Jersey Turnpike, originating in the boom years following World War II, launched with the largest toll-road bond issue in history up to that time—$250 million in thirty-five-year bonds. The turnpike agencies in Pennsylvania and New Jersey had power, patronage, and unending streams of revenue from toll booths and service plazas operating twenty-four hours a day, every day of the year—circumstances that led to instances of corruption in both states.

For the Philadelphia region, beginning with the Lancaster Turnpike of 1795 and continuing into the twenty-first century, turnpikes achieved transformational change for the movement of people and goods. Private investment and tolls achieved improvements in road surfacing, speed, and safety beyond the capacity of public financing. The resulting turnpikes contributed to forming regional ties between Philadelphia and nearby communities in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware while also forging connections to travel and commerce of the nation.

Charlene Mires is Professor of History at Rutgers-Camden and Editor in Chief of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University