Burlington County, New Jersey

Essay

Settled primarily by Quakers in the seventeenth century, Burlington County occupied a strategic location between the Delaware River and the Atlantic coast that made it a site for commercial and agricultural development as well as spiritual refuge. Marginalized over time as money and power shifted elsewhere, the area diversified in the formation of forty communities spread over 819 square miles stretching from the Delaware River to the Pine Barrens near New Jersey’s eastern shore.

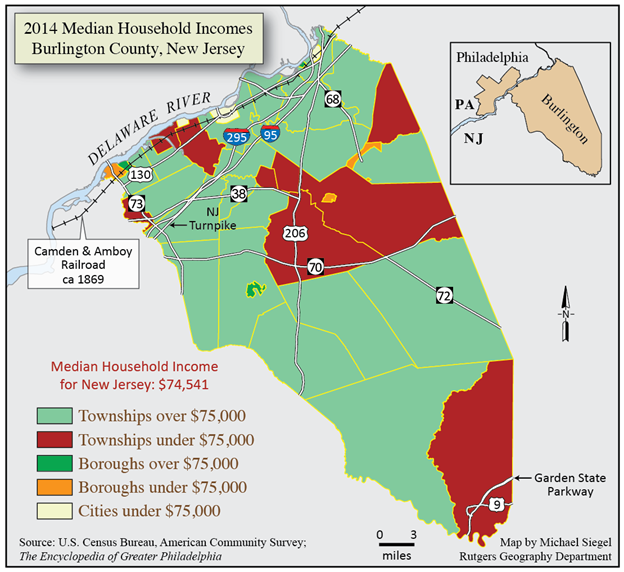

( Michael Siegel, Rutgers Geography Department)

Originally occupied by the Lenape, the area became an important crossing point of the Delaware River with the arrival of the first Dutch settlers in the mid-seventeenth century. In 1676 a group of Quakers, including William Penn (1644-1718), obtained title to West Jersey. The following year proprietors adopted the West Jersey Concessions, a liberal system of government and basic laws granting religious freedom, trial by jury, and security from arbitrary arrest, prompting further migration from England. Quakers from Yorkshire landed near Raccoon Creek, where they encountered a few Swedish households, then proceeded to Chygoes (Burlington) Island to negotiate terms with the Indians. Choosing land from the Assunpink Creek to the Rancocas Creek, known as the First Tenth, they were soon joined by a second ship’s cargo of London Friends, who purchased the land between the Rancocas and Timber Creeks, known as the Second Tenth. For mutual protection, the two settler groups jointly agreed to build a town, known first as New Beverly, then Bridlington, and finally Burlington, after a village in Yorkshire. In 1681 it became the capital of West Jersey.

Soon after its founding, Burlington City became a major colonial port maintaining a brisk trade with Ireland, Great Britain, Europe, and the West Indies. The city’s first shipyard was established in 1698, and shipbuilding quickly became an important economic activity. With the establishment of other towns, the assembly formed Burlington County in 1694. Unable to exercise central control over the sprawling settlements in West Jersey, however, the proprietors in 1702 surrendered their title to the Crown, which then reunited West with East Jersey and named Burlington and Perth Amboy, the capital of East Jersey, co-capitals.

Favorable to the Crown

With its stake in maintaining trade with England, Burlington City remained favorable to the Crown during the years leading to the American Revolution. Resistance to British authority concentrated instead in Mount Holly—also founded by Quakers, in 1676—at a location farther inland along the Rancocas Creek, where grist and sawmills emerged to support the predominantly farm community. When war came to New Jersey in 1776, both communities had to defend themselves, but when British troops threatened Trenton, the capital shifted temporarily to Mount Holly. In 1796 the county seat shifted there from Burlington.

While the great portion of the county remained agricultural in the early years of the new republic, industry did emerge in several locations. Shipbuilding declined in Burlington City as Philadelphia’s dominance of the industry grew, but shoemaking emerged as a major industry in the early nineteenth century. Other products followed, including patent medicine, hats, iron stoves and pipe, terra cotta, carriages, and canned fruits and vegetables, which were shipped by water and rail to markets throughout the United States.

By 1790 Burlington County had the largest Black population and largest number of free Blacks among the state’s five southern counties, the result of Quaker opposition to slavery. During the 1820s free blacks who had originally lived in scattered areas on or near farms or in the woods began to form settlements of their own. These included Cross Roads in later Medford Township, Ingletown in later Shamong Township, and several in Evesham Township, a Quaker community dating back to 1688. The oldest of these was Colemantown, along Elbow Lane in a part of Evesham that became part of Mount Laurel after its incorporation in 1872. Named for Charles Coleman, the area’s first Black homeowner, a modest edifice that served as meeting house for different denominations and a school for Black children was soon accompanied by a cemetery designated for Blacks. Shortly after the Civil War, congregants built a new home of worship, known as Jacob’s Chapel after Jacob Mitchell, an African Methodist Episcopal minister known for his success in building other congregations in the area. The chapel subsequently became a stop on the Underground Railroad running from Delaware through Woodbury in Gloucester County and on to Mercer County. Another Black community formed in Mount Holly. Known as Timbuctoo, it first formed in 1826 when four African American men, all believed to be escaped slaves from Maryland, purchased parcels of land from a Quaker businessman. In addition to farming, residents found employment in two brickyards north of the settlement owned by Quakers. Reaching its peak in the nineteenth century with some 125 residents, the area supported a school, Zion Wesleyan Methodist Episcopal African Church, and a cemetery.

(Wikimedia Commons)

New Transit Aids Growth

Burlington City’s growth, and that of towns emerging along the Delaware River between Philadelphia and New York, was aided by transportation advances, starting with steamboat service to Philadelphia inaugurated in 1788. The advent of the Camden and Amboy Railroad and its related entity, the Delaware and Raritan Canal Company, both chartered in 1830, further spurred development. When the 44-mile-long canal opened in 1834, passengers moved by rail and freight by canalboat. Protected from competition by the state legislature through a partial merger producing what was referred to as the Joint Entities, together the canal and railroad assured profits over a heavily traveled route across New Jersey. Among the many products shipped north were Pennsylvania’s anthracite coal and such agricultural goods as flour, cornmeal, grain, and feed. By 1839, as it absorbed other rail lines, including the Pennsylvania-chartered Trenton and Philadelphia Railroad, the Camden and Amboy controlled all rail service between Camden and New York City

Communities along the Joint Entities route thrived. These included, in addition to Burlington, nearby Florence, initially known as High Banks. Its riverfront location a short boat ride from Philadelphia made the area a popular recreation destination. In 1849 investors from New York, recognizing the area’s residential potential, purchased six hundred acres to form the Florence City Company. Despite providing amenities to attract buyers, including a wharf, hotel, landscaped streets, and brick houses, the venture faltered and was sold in 1854. It was up to manufacturers, then, to restore the area’s prospects with the formation of the Florence Iron Works in 1858. Sold nine years later to R.D. Wood & Company (based in Millville, Cumberland County), the iron works expanded after inducing the Camden and Amboy to build a spur to its plant. The company built modest homes for its workers, a library, and other amenities. It fabricated water and gas pipes, fire hydrants, valves, and other cast iron products. Sold to the Griffin Pipe Foundry in 1962, the facility subsequently became part of a larger manufacturing corporation, Amsted Industries, whose plant in Florence produced ductile iron pressure pipe used by the construction industry until 2009.

Immediately adjacent to Florence emerged the town of Roebling, named for the company founded by John Roebling (1806-1869) that designed and built the Brooklyn Bridge, among other structures. Based in Trenton for a number of years, the family enterprise, seeking cheaper land to build a new wire rope plant and its own steel mill, bought a 115-acre farm fronting the Delaware River in 1904 in the small village of Kinkora. There it laid out a model company town consisting of 750 homes for its workers as well a hospital, school, post office, and other facilities for their use. The company sold the mill to Colorado Fuel in 1953, which ran the plant until it closed in 1974. Although the mill was declared a federal Superfund site in 1983, the community of some eight thousand residents remained in place as part of Florence Township.

Changing Identity

Closer to Philadelphia, at the confluence of the Delaware River and Rancocas Creek, steamboat and rail connections spurred development over time. A scattered group of squatter farms in the mid-nineteenth century, the area known originally as Goat Town attracted the interest of Philadelphia investors who conceived a resort area at the location. When new rail connections diverted vacationers to the Jersey shore instead, manufacturing took over with the introduction of woolen and worsted textiles, led by the German-American William F. Taubel (1863-1957) whose company ultimately extended to thirty-three locations in the eastern United States. The area was absorbed first into Cinnaminson, then Delran Township before emerging as independent Riverside Township in 1895. Two years later the area gained a new identity when the Swiss-German immigrant Theophilus Zurbrugg (1861-1912) moved his Keystore Watchcase Company from Philadelphia to Riverside, where he set up his factory in the town’s first resort hotel. The company soon added a metal work facility, and the construction of low-cost housing further put the company’s mark on the town. In 1908 the company relocated to the Watch Case Building, which remained a local landmark. In contrast, the Township of Riverton, which also split from Cinnaminson, became the location of prime Victorian homes constructed by wealthy Philadelphians, whose settlement there as early as the 1850s fostered one of the nation’s first yacht clubs, known for its stunning Victorian clubhouse.

Farther inland along the Rancocas emerged another company town under the direction of Hezekiah B. Smith (1816-87), whose walled compound included factory buildings and worker housing as well as Smith’s mansion. Originally a cotton and textile plant, the facility known as the H.B. Smith Machine Company was converted to a woodworking plant in the 1860s. Located within what became Eastampton Township, the Smith factory was connected to Mount Holly by a one-mile wooden rail line. Following the factory’s closure during the Depression, Smithville was incorporated into the Burlington County park system.

Quite a different industry emerged in the southeastern sector of the county within the Pine Barrens in what was to become Washington Township. Drawing on an abundance of bog ore in area streams and rivers and charcoal for smelting, Charles Read (1715-74), a Philadelphia merchant who had moved to Burlington in search of a political career, established the Batsto Iron Works along the Batsto River in 1766. When Read fell into financial difficulty, he sold the plant to area investors, who oversaw iron production at more than thirty forges and furnaces throughout the Pines area. The Batsto plant prospered for nearly a century under the direction of the Richards family, which bought the works in 1784. When demand for iron ore slackened, the company tried unsuccessfully to shift to glassmaking and fell into receivership. In 1876 Philadelphia businessman and founder of Bethlehem Steel Joseph Wharton (1826-1909) purchased the plant and a number of related properties. Managed after Wharton’s death until 1954 by the Girard Trust in Philadelphia, the historic Batsto Village and associated museum subsequently became a prime visitor destination in South Jersey.

(Wikimedia Commons)

Industries Rise and Fall

The same year Charles Read launched the Batsto works, he constructed another facility, the Aetna Furnace, on nine thousand acres at the edge of the Pine Barrens in an area known as Upper Evesham, but later incorporated in 1847 as Medford. In 1766, Read followed with a second facility, the Taunton furnace and forge, which produced among other products cannon balls for the American Revolution. The collapse of Read’s iron empire forced the furnace’s closure in 1773 after which the area lay fallow until its sale in 1926 to a developer who converted it to a resort-like community of log cabin cottages in the Pines known as Medford Lakes. Although Read’s venture collapsed, other industry emerged, including glassmaking. Dating to 1825 with the formation of a farmers’ co-op that made window panes, glass remained in production in the township for ninety years.

Benefiting from its location as the port closest to the Pine Barrens and Philadelphia in the era before the Raritan Canal opened, the village of Lumberton diversified its agricultural base to incorporate textile mills and a steel furnace that remained profitable for the first decades of the nineteenth century. In anticipation of its prospects, the town authorized the layout of a city-style grid geared for residential development, but growth did not follow. Established as a township in 1860 when the population was just over 1,800, the community lacked growth until the 1950s, when its farmland began to give way to suburban development. A town of just 1,325 in 1950, Lumberton’s population climbed to 2,833 in 1960 and to 12,228 in 2020.

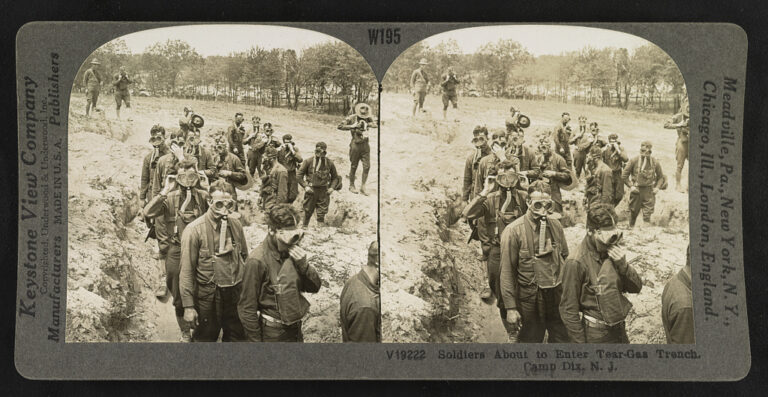

Much of the county inland from the Delaware River remained largely agricultural and rural into the twentieth century. Establishment in 1917 of a staging and training center for World War I, Fort Dix, as it was formally named in 1939, in New Hanover Township served as a base for the New Deal’s Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s. Its construction boosted area employment in Mount Holly some ten miles distant, ultimately providing consumers for town products and homes. The buildup of personnel during World War II further boosted area homebuilding.

Growth came not just from the expansion of Fort Dix, which merged with McGuire Air Force Base and the Lakehurst Naval Air Engineering Station in 2009. The completion of the New Jersey Turnpike in 1952 further boosted development, nowhere more directly than at Exit 4, in Mount Laurel. A town of only several thousand people in 1940 despite its sprawling territory over twenty-two square miles, Mount Laurel’s population grew modestly during World War II to 2,800 before witnessing accelerated growth in the 1950s and 1960s after the turnpike opened. In 1970 the population reached eleven thousand. With so much empty land, the township attracted not just tract housing but whole new communities through a new procedure for integrated land development, planned unit development. When Larchmont opened in 1970, it was only the second such development to be built in New Jersey. Spurred by construction of nearly three thousand new housing units, many of them in planned unit developments, the population climbed to 17,000 by 1980 and 30,000 in 1990. To this were added three industrial parks and a host of businesses taking advantage of easy access to the turnpike and I-295, which ran parallel and only a mile distant from the turnpike. By 2000 Mount Laurel’s population had climbed to forty thousand, transforming the once agricultural landscape into a prototypical exurban landscape tied intimately to the automobile.

Unwelcome Changes

Growth brought unwanted change to Black longtime residents of Mount Laurel. Faced with rising housing costs, they sought a change in local zoning to allow multi unit housing, only to be told that if they could not afford to stay in Mount Laurel, they could move to Camden. Ultimately the New Jersey State Supreme Court supported their cause by ruling in 1975 and 1983 that every community in the state would be responsible for providing its “fair share” of affordable housing. One result of that Mount Laurel doctrine, as it came to be called, was the construction of the Ethel Lawrence Homes, so named for a chief plaintiff in the lawsuit, a model of affordable development in Mount Laurel practically indistinguishable in quality and form from the many gated communities nearby.

The expansion of Willingboro, a community founded by Quakers dating back to 1688 from an agricultural community of less than one thousand in 1950, raised racial issues of another kind. By introducing 11,000 homes on some 4,900 acres of open land, developer William Levitt (1907-94) transformed the township between 1958 and 1972 to a community of 47,000 people, renaming it Levittown. Levitt barred African Americans from purchasing the new homes, a position that held until a Black soldier from Fort Dix successfully sued the town, challenging its right to receive federal subsidies while discriminating. Following the decision by New Jersey’s Supreme Court, Levitt adopted an active integration program, and by 1970 Willingboro’s Black population had reached 11 percent. As the numbers continued to grow, panic selling by whites ensued, so that by 2020, though the population had fallen to thirty-one thousand, whites represented only 13 percent of that total. By referendum in 1963, the township reverted to its original name of Willingboro.

The growth of automobile registrations in the early years of the twentieth century increased demand for river crossings between Pennsylvania and New Jersey. In 1922 businessmen in Palmyra, a borough located along the rail line and about halfway between Trenton and Philadelphia, initiated car ferry service to the growing neighborhood of Tacony in Philadelphia. Demand grew so quickly, company directors decided to follow the example of the Delaware River (later Benjamin Franklin) Bridge after it opened seven miles to the south in 1926. The Tacony-Palmyra span proved equally successful after it opened to traffic in 1929, quickly falling behind its ability to meet demand and prompting growth in the surrounding area. The bridge was privately owned and operated until 1948, when it was purchased by the Burlington Bridge Commission.

As in practically every expanding metropolitan region after World War II, shopping malls proliferated in Burlington County. Opened in 1963 in Moorestown Township, the Moorestown Mall was overshadowed from the start by South Jersey’s first mall, in Cherry Hill, built two years earlier and only three miles away. Although the Moorestown Mall counted among its early tenants the Sears Roebuck store that left Camden for the new facility, it encountered increasing difficulties over the years. Parts of the mall were renovated in 1986 to meet competition and completely remodeled in 1993 and 1994 after a serious fire damaged the northeast quarter. As bricks-and-mortar retail sales tumbled in the second decade of the twenty-first century, major stores closed or departed, including Macy’s, Lord & Taylor, and Sears. To stem losses, the Pennsylvania Real Estate Investment Trust (PREIT), after purchasing the mall from the Rouse Company, planned alternative uses on portions of the property, including three apartment buildings and a hotel.

Burlington Mall

Developers took a similar tack in Burlington Township, the 14-square-mile area that separated from Burlington City in 1894. Once the home for 600,000 square feet of retail sales, the 97-acre Burlington Mall was earmarked after its closure in 2018 for mixed-use, including as many as five hundred townhomes and multiple restaurants. Other redevelopment in the area benefited from an aggressive state program, New Jersey Grow, aimed at retaining business. When Burlington Coat threatened to move its national headquarters from Burlington Township to Pennsylvania, a $40 million state subsidy issued in 2012 enabled the company to move a few miles up Route 130 to build a new facility in Florence. In Moorestown, Lockheed Martin, the county’s largest business, with some 3,400 workers, took advantage of a $40 million state subsidy to obtain a $100 million government contract for missile research, enabling the company to retain many workers considered otherwise vulnerable to layoffs.

In Burlington City, closure of the US Pipe facility in 2008 left a prime site for redevelopment, but grand plans for restoring the former company headquarters and the surrounding facilities floundered until Amazon opened a million square foot fulfillment center on the 177 acre property in 2019. Among the possibilities for the remaining 26 acres was an indoor waterfront park and resort hotel. Both initiatives illuminated the shifting role of prime locations in the twenty-first century.

Shifting regional demographics affected several county communities in complex fashion. On the western side, the once thriving industrial township of Riverside, as it stagnated, attracted a wave of Brazilian immigrants looking for affordable housing. Their presence brought a host of new small businesses, but also clashes with established residents as their numbers reached as many as five thousand people in the town of only eight thousand. Farther east, the decline of conditions in subsidized housing in Mount Holly prompted a redevelopment initiative that spurred displacement and a prolonged court contest over the future of the site. The dispute was ultimately resolved, but not without highlighting the mixed response to redevelopment.

Other towns benefited from a different kind of investment: public transportation. The completion of NJ Transit’s River Line light rail connection between Camden and Trenton in 2004 did not make a profit, but it lifted the fortunes of towns along its route. Constructed on the former Camden-Bordentown section and Bordentown-Trenton branch of the Camden and Amboy Railroad, the line boosted population and new investment at stops along the line: Riverside, Delanco, Beverly, Burlington, Florence, and Bordentown. The county also pursued a companion reinvestment strategy to enhance commercial outlets along the parallel Route 130 corridor to attract new housing and boost population along the line even as it declined in the exurban areas to the east. Although Bordentown’s population growth lagged behind other towns along the corridor, its easy access to the New Jersey Turnpike prompted a boom in warehouse development.

(Wikimedia Commons)

As of 2020, the Burlington County population was 462,269—72 percent white, 18.7 percent Black, and 9.2 percent Hispanic—and the median household income was $90,329. Land use from west to east became less dense as older suburban areas gave way to larger developments built where farms once dominated, to smaller older towns like Medford, which retained their early roots, to more scattered housing and facilities in communities within the Pine Barrens.

Howard Gillette is Professor Emeritus of History at Rutgers-Camden and co-editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- West Jersey History Project

- Delaware River Heritage Trail

- Evicted from the American Dream: The Redevelopment of Mount Holly Gardens (NJ Division of Public Interest Advocacy)

- Roebling: A little hamlet with a whole lot of history and a growing attraction for tourists (NJ.com)

- Did you know New Jersey had a Levittown? (WHYY)