Eminent Domain

Essay

Eminent domain refers to the right of the government to take private property and convert it into a public use. Across the Greater Philadelphia region, state and local governments have used this power to spur economic growth by attracting capital investment. However, governments across the region enacted new laws to provide greater protections for property owners as well as promote economic development in the wake of the Supreme Court decision Kelo v. New London (2005). That case prompted local and national backlash as the court ruled in favor of taking private property for private use, authorizing a broader interpretation of government’s ability to condemn property.

The power of eminent domain has its foundation in the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which specifies that in order for the government to take private property, two conditions must be met: first, taking property must be done for a “public use,” and secondly, the government must provide “just compensation” to owners of condemned land. While the topic of eminent domain received little attention during the Constitutional Convention and ratification debates, legislators and judges subsequently saw it as a necessary power for achieving important national goals. Although governments in the Philadelphia region did not exercise eminent domain in the nineteenth century, the answer to how the Supreme Court would interpret the Takings Clause came in Kohl v. United States (1876). In Kohl, the court ruled that the federal government could take private property in Cincinnati, Ohio, for the construction of a post office, courthouse, and other public offices. These projects had a direct and immediate public benefit, and such appropriations would enable the government to execute legitimate functions. However, over the course of the twentieth century, the line between public and private interests became increasingly blurred, as legislators and judges sought broader interpretations of eminent domain’s “public use” provision.

Beginning in the 1940s, officials in Philadelphia seeking to combat economic underdevelopment or “blighted” land began pursuing redevelopment efforts by enticing investors to bring private investment dollars into decaying neighborhoods. This strategy gained support in 1954 when the Supreme Court ruled in Berman v. Parker in favor of the District of Columbia Redevelopment Act (1945), which—in contrast to Kohl—involved the transfer of private land to developers for private use. Moreover, the Pennsylvania legislature granted extensive authority to the state’s local governments to alleviate blight by enacting the Urban Redevelopment Law (1945) and the Housing and Redevelopment Assistance Law (1949).

In Philadelphia, with insufficient funds to accomplish neighborhood renewal by itself, planners had to convince private investors they would not be alone in taking a chance on a revitalizing area. If developers chose to buy and improve properties in a neighborhood, their investments would be protected by a broader pattern of reinvestment that would improve surrounding properties as well. Hence, use of eminent domain was considered integral to economic development. Beginning in the 1940s, it became commonplace for city officials to invoke eminent domain to clear blight in an effort to attract much-needed capital. Over the next several decades, policymakers used their authority to take residential and commercial property and transfer it to private developers to advance long-term redevelopment strategies. In the 1950s, acquisitions were instrumental in inaugurating Independence Mall, a plaza extending three blocks north of Independence Hall. The 1960s saw large-scale redevelopment campaigns undertaken in Society Hill and in the “Black Bottom” district of West Philadelphia, followed by Market Street East and Chinatown in the 1970s.

(Wikimedia Commons)

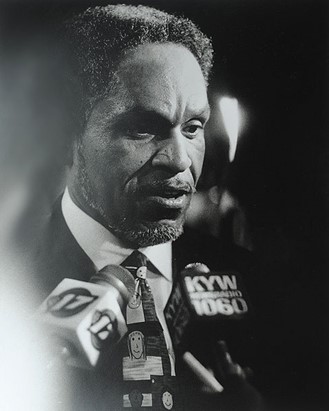

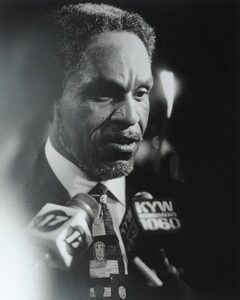

Between 1992 and 2007, Philadelphia officials invoked eminent domain over four thousand times, with most of the takings for private reuse. In the 1990s, Mayor Edward Rendell (b. 1944) used eminent domain to complete a multidecade effort to build the Pennsylvania Convention Center, and the administration under Mayor John F. Street (b.1943) launched the controversial Neighborhood Transformation Initiative in 2001, which focused redevelopment efforts on Brewerytown in North Philadelphia and Mill Creek in West Philadelphia.

(Wikimedia Commons)

The most controversial uses of eminent domain occurred when city government imposed blanket condemnation across entire neighborhoods. Debates over the constitutionality of such blanket condemnations to achieve larger development plans were reignited by Kelo vs. New London. In that case, officials in New London, Connecticut, condemned 114 properties and transferred them to Pfizer, the pharmaceutical company. Local officials justified the decision by claiming that the expected jobs and revenue generated by the project would benefit the local economy. After the high court’s ruling supporting the rationale, state governments pursued changes to mitigate the perceived abuses.

Regional Post-Kelo Changes

In the wake of Kelo, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware enacted laws restraining state and local governments’ authority to take private property. Pennsylvania lawmakers enacted the Property Rights Protection Act (2006), which barred the use of eminent domain to take private property and transfer it to a private enterprise. The law also adopted a stricter definition of what counts as blight. Before the 2006 law, the state’s Urban Redevelopment Law permitted condemnation if the land was “economically and socially undesirable.” This vague conception of blight left too much discretion in the hands of government officials to use their power to condemn properties. Although supporters saw the legislation as a net success, a perceived shortcoming was that it permitted certain counties such as Philadelphia and Delaware to continue to use existing blight designation for another seven years after its passage.

In 2007 in Delaware, Wilmington officials proposed an urban renewal project that would use eminent domain to condemn sixty-two properties, including thirty-eight businesses. To make their case for condemnation, local legislators invoked the state’s Slum Clearance Redevelopment Act, arguing that the area fit the law’s blight description of being a “social or economic liability.” As in Pennsylvania, critics contended that this standard was exceedingly vague and that the community’s conditions did not meet it. Although the properties taken were to be transferred to private enterprises, officials claimed that the higher tax revenues the project would generate would confer a public benefit. In response, in 2009, Delaware amended its eminent domain laws by sharply limiting the power of the government to take private property to execute an economic development plan. In contrast to Kelo, the legislation banned takings on the basis of potential economic benefits.

While New Jersey did not alter its eminent domain laws until eight years after Kelo, local controversies forced a statewide conversation about its effects and where to draw the boundary between public good and private gain. In 2003, the state became the center of controversy over a redevelopment project in Mount Holly. Township officials sought to condemn 325 homes in the “Gardens” section to build higher-priced housing and businesses. Threats of displacement mobilized community members to form the Mount Holly Gardens in Action. The organization contested the township’s blight designation, arguing that the condemnation had a “disparate impact” on the only largely Black and Hispanic community in Mount Holly. As part of a settlement, local officials reached a compromise, agreeing to build replacement homes for twenty of the original 325 original occupants in exchange for the proposed redevelopment plans. Similarly, in 2007, residents of Camden’s Cramer Hill neighborhood challenged an ordinance to acquire several parcels of land on the basis that the taking would increase the number of affordable housing units in the city. In response to public outcry at the local and national levels, officials passed the New Jersey Eminent Domain Act in 2013, which established “non-condemnation redevelopment areas.” These areas restricted local governments from using their eminent domain powers within designated areas, requiring them to use alternate tools such as tax incentives or subsidies to attract investment.

Nicholas Robinson is an assistant professor of Political Science at Otterbein University. His research interests include community benefits agreements, democratic theory, distributive justice, gentrification, and urban redevelopment. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- U.S. Supreme Court rules PennEast pipeline project can use eminent domain to take N.J. state land (WHYY, June 29, 2021)

- PennEast shelves plan to build pipeline on public lands in New Jersey (WHYY, September 23, 2021)

- Delco forges a process to turn massive Don Guanella property into ‘second to none’ park (WHYY, March 19, 2022)

- Remaking Sharswood: Taking a neighborhood through eminent domain in the name of ‘transformation’ (WHYY, March 7, 2016)

Links

- Cultural Landscape Report of the Independence Mall (Independence National Historical park)

- The Creation of Independence National Historical Park and Independence Mall (Thesis, University of Pennsylvania)

- Twenty-First Century Urban Renewal in Philadelphia: The Neighborhood Transformation Initiative and its Critics (Planners Network)

- History of Community Displacement in Black Bottom (The Blackbottom Project)