Clothespin

Essay

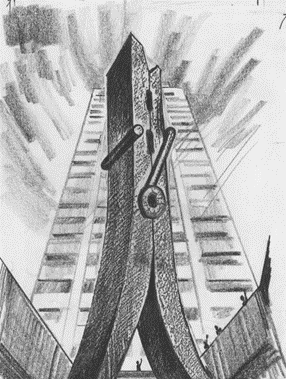

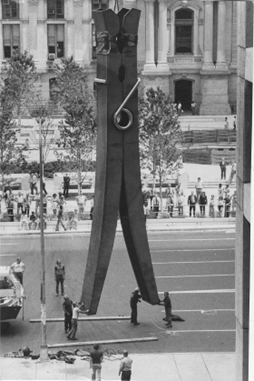

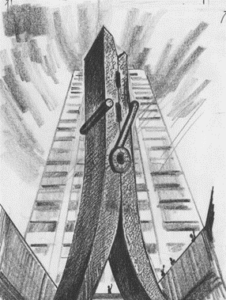

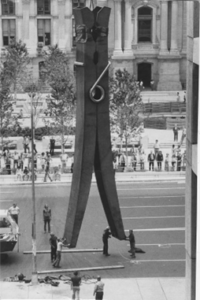

Designed by renowned Swedish-American artist Claes Oldenburg (b.1929) and unveiled during Philadelphia’s year-long Bicentennial celebration in 1976, Clothespin is a 45-foot, 10-ton Cor-Ten steel sculpture at Centre Square Plaza (Fifteenth and Market Streets). The first major public artwork by Oldenburg in Philadelphia, this one-of-a-kind sculpture transformed the downtown landscape. An undeniable Center City landmark across the street from City Hall, the monumental work of public art has been celebrated and maligned since its installation. Across the spectrum of praise and scorn, the sculpture inspired a persistent question: Is it really just a giant clothespin?

As a crane lowered Clothespin onto its pedestal on June 25, 1976, Oldenburg explained that the sculpture is indeed a giant clothespin, but, at the same time, it transcends a common clothespin. Rather than simply replicating an ordinary clothespin, Oldenburg’s design rearranged its elements, elongating its functional proportions to create a large-scale, anti-functional clothespin. It was inspired not only by common clothespins, but also by a significant work of art: The Kiss (1908) by Constantin Brancusi (1876-1957). Among the several versions of The Kiss, the fourth (1916) is housed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Considering The Kiss while observing Clothespin, the viewer might be struck by the way the two halves of the sculpture embrace. The natural shades of orange, red, and brown produced by the gradual weathering of Cor-Ten steel add a sense of warmth to the embrace. The viewer’s attention might also be drawn to the spring that joins the two halves and resembles “76,” a reference to both 1976 and 1776. With 1776 in mind, the sculpture may appear reminiscent of the Liberty Bell, with a central crack above a bell-shaped bottom.

The multiplicity of potential interpretations of this sculpture, which interrupts ordinary life while inviting reflection on the limits of the “ordinary,” has garnered praise from critics and passersby alike. The reinterpretation and reimagination of ordinary objects is a persistent theme in Oldenburg’s work. Oldenburg’s early sculptures, in the 1950s, consisted of repurposed materials, such as cardboard. In the early 1960s, he experimented with plaster to create artworks resembling everyday objects such as familiar food items, while also organizing performative “happenings.” He emerged as a leader of the Pop Arts movement with his large-scale “soft sculptures,” using materials like vinyl to reimagine common items such as a toilet (Soft Toilet, 1966), food (French Fries and Ketchup, 1963), and clothespin (Clothespin, 4-ft, Soft Version, 1975). In the late 1960s and early 1970s, he turned his attention toward public works more explicitly, creating large-scale sculptures including Giant Three-Way Plug (Cube Tap) (1970), housed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (2010), and the more controversial Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks (1969; recreated and reinstalled 1974) at Yale University.

It was rumored in local media that Oldenburg proposed a controversial design for Centre Square Plaza: a 45-foot screw, considered a political statement given the site’s proximity to City Hall. Although Clothespin appears more benign than a screw, the design spurred controversy and criticism. In 1974, after the project was publicly announced, columnists and concerned citizens sparred over Clothespin in the pages of the Philadelphia Inquirer. Some detractors pondered whether the unusual sculpture was intended to be a joke on Philadelphia; others mocked the apparent simplicity of the design and wryly suggested that a gigantic pretzel or hoagie might be more appropriate. At the time of its installation, Mayor Frank Rizzo (1920-91) critiqued the sculpture on public television, noting that it reminded him of childhood chores.

Percent for Art Program

Philadelphia’s Percent for Art program, established in 1959, helped make this hotly debated project possible and attractive. The first of its kind in the country, this program, developed through a dual Redevelopment Authority resolution and municipal ordinance, required developers to allocate a minimum of 1 percent of new construction or major renovation costs for original works of art. Clothespin was commissioned by developer Jack Wolgin (1916-2010) through Percent for Art as part of his $80 million Centre Square project. The project, built on land cleared by the Redevelopment Authority, consisted of the construction of twin high-rise office towers designed by Vincent Kling & Associates, joined by an atrium adjacent to a subway entrance.

Wolgin was not only a developer, he was also an avid art collector and former chairman of the Philadelphia Art Commission. His interest in Clothespin was piqued by Oldenburg’s drawing of a clothespin on an exhibition poster for Claes Oldenburg: Object into Monument (1972) at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Wolgin commissioned two additional artworks at Centre Square: Milord la Chamarre (1973; installed 1976) by Jean Dubuffet (1901-85), in the atrium well, and a series of banners by Alexander Calder (1898-1976), hung from the atrium roof.

Although Centre Square’s towers adhered to the local tradition of remaining beneath the height of the William Penn statue on top of neighboring City Hall, the projects supported by Percent for Art broke with the traditional, neoclassical design of City Hall’s public sculptures. Along with other modern artworks installed in 1976, including the then-temporary placement of LOVE (1976) by Robert Indiana (1928-2018) at John F. Kennedy Plaza, the sculptures at Centre Square positioned Philadelphia as a leader in the changing world of urban public art.

In 1981, Oldenburg created another large-scale public sculpture in Philadelphia with his wife and collaborator Coosje van Bruggen (1942-2009): Split Button (1981), on the University of Pennsylvania’s campus. Two years later, Clothespin appeared in the film Trading Places (1983). In 2001, Oldenburg and van Bruggen received an award from the Fairmount Park Art Association celebrating Clothespin’s transformative impact and twenty-fifth anniversary. After van Bruggen passed away, the first sculpture Oldenburg completed alone was Paint Torch (2011) at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Altogether, Philadelphia is home to four Oldenburg sculptures—more than any other city in the world.

Clothespin, the city’s first public artwork by Oldenburg, is a meeting place for Philadelphians, an iconic destination for tourists, and an inspiration for other artistic projects, such as All Power to All People (2017) by Hank Willis Thomas (b. 1976). Thomas’s sculpture, an oversized Afro pick temporarily installed on Thomas Paine Plaza (2017) and permanently housed at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (2018), invites critical reflection on representation and identity while, like Clothespin, making the ordinary extraordinary.

Kristin Hankins is a Ph.D. candidate in American Studies at Yale University. She studies urban history and geography, public space, and visual culture. (Information in this essay was current at the time of publication.)

Copyright 2021, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- After All These Years: Political, Erotical and Mystical Claes Oldenburg (Phillyhistory.org)

- Cartoons for Centre Square Philadelphia Banners

- Claes Oldenburg & Coosje van Bruggen

- Claes Oldenburg, 93, created giant sculptures that became icons of Philly (WHYY)

- Clothespin (Oldenburgvanbruggen.com)

- Clothespin, 4-foot, Soft Version

- Dueling icons: Jamie Lee Curtis and Clothespin, from Trading Places. (Philebrity.com)

- French Fries and Ketchup

- Giant Three-Way Plug

- Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks

- Milord la Chamarre

- Object into Monument

- Paint Torch

- Public Art in Philadelphia (Temple University Press)

- Sculpture by the Way

- Soft Toilet

- Split Button

- The Kiss