Art Colonies

Essay

Outside the urban core of Philadelphia, the picturesque rural landscape proved a significant draw to many artists in search of the purportedly simple, wholesome, and moral quality of countryside living. Whether planned and intentional or more organic and serendipitous, colonies like those in New Hope, Chadds Ford, and Rose Valley in Pennsylvania, and Arden and Wilmington in Delaware, provided easy access to the metropolitan centers of Philadelphia and New York, with their networks of galleries and educational institutions fostering opportunities to sell artwork, teach, and make social and professional connections. Part of a widespread growth of art colonies in Europe and elsewhere in the United States, such communities around Greater Philadelphia played a prominent role in shaping the artistic culture of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

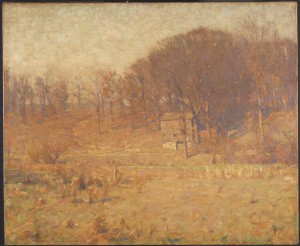

Rural or small-town art colonies arose in large part because of the increasing availability of old farmhouses and disused industrial properties. One such example was New Hope, a mill town on the Delaware River in Bucks County, north of Philadelphia, which became an important incubator of impressionist painting in Pennsylvania. The colony’s genesis is generally traced to the painter William Langson Lathrop (1859–1938), who in 1898 took up residence on the property of the abandoned Phillips’ Mill, owned by his childhood friend George Morley Marshall (1858–1935). Judging it a beautiful, accommodating home, Lathrop purchased part of the mill site from Marshall the following year and moved his family there from Ohio. Around the same time that Lathrop was discovering the area, painter Edward Willis Redfield (1869–1965) took on ownership of a family property just north of New Hope and likewise came there to work.

With the two artists becoming increasingly visible on a national level, numerous other professional artists moved to Bucks County throughout the first decades of the twentieth century, aided by the magnetic, community-oriented personality of William’s wife, Annie Lathrop (née Burt, 1865–1935), and the 1907 arrival of the prominent painter and educator Daniel Garber (1880–1958). Notable artists including Morgan Colt (1876–1926), M. Elizabeth Price (1877–1965), Charles Rosen (1878–1950), George Sotter (1879–1953), Robert Spencer (1879–1931), Rae Sloan Bredin (1880–1933), and John F. Folinsbee (1892–1972) all contributed to the distinctive artistic culture of New Hope and the well-regarded Pennsylvania Impressionism school. The colony drew attention for its residents’ successes at exhibitions in Philadelphia, New York, and as far afield as the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915.

Graphic Artists and Craftspeople Gather

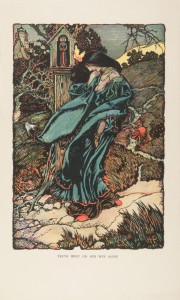

Although painters dominated the New Hope colony, graphic artists were also forming communities around Greater Philadelphia. Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, southwest of Philadelphia in the Brandywine River Valley, is perhaps most famous as the home of the Wyeth family of artists, but it was host to a colony associated with the “Brandywine School” of illustrators, centered on the influential artist and educator Howard Pyle (1853–1911). Dissatisfied with Philadelphia’s institutions of higher education, in 1898 Pyle began teaching students during the summers at Turner’s Mill in Chadds Ford. Beginning in 1900 he held more formal, extremely popular classes at his home and studio in Wilmington, Delaware, drawing another community of illustrators to that city. His strong presence continued to be felt even after his death among the artists living, working, and teaching upriver in Chadds Ford, carrying on the Brandywine School style as well as Pyle’s legacy as an educator and advocate for the illustration profession.

From the late nineteenth century, the Philadelphia area was also home to colonies associated with the Arts and Crafts movement. Unlike the New Hope artists, who placed particular emphasis on the rural landscape as a means of fostering an artist’s triumphant individuality, Arts and Crafts advocates saw the agrarian character and vernacular architecture of the area around Philadelphia as important components of their romantic, community-driven notion of life as art. Frequently active in socialist politics, they stressed communal spirit, honest labor, and the value of handicrafts such as ceramics, metalwork, and furniture-building, and their utopian colonies were designed to foster a holistic sense of artistic activity.

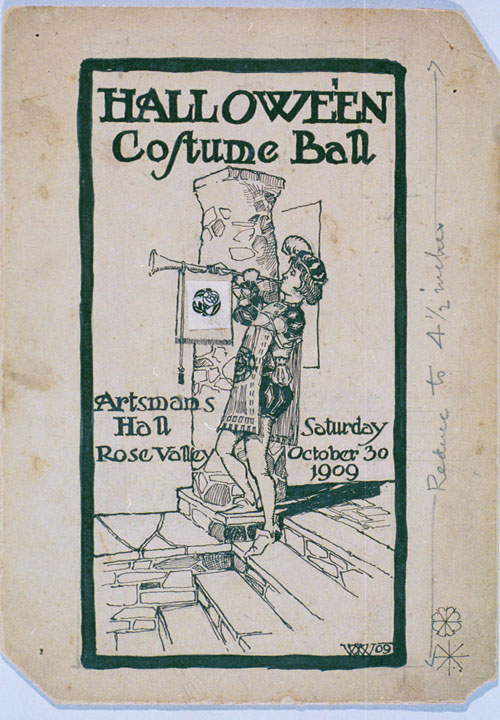

The best known of these, Rose Valley, was, like New Hope, built in and around an abandoned mill. Founded near Moylan, Pennsylvania, in 1901 by Philadelphia architect William Lightfoot Price (1861–1916), Rose Valley and its Delaware counterpart Arden—founded outside Wilmington in 1900 by Price and sculptor Frank Stephens (1859–1935)—included workshops for furniture, metalwork, ceramics, and bookmaking, as well as communal guildhalls and a number of cottages and larger houses for artists and their families. Selling work through periodical advertisements and shops in Philadelphia proper, and, in the case of the Rose Valley Association, publishing The Artsman journal from its city press, these communities and their residents made important contributions to the dissemination of Arts and Crafts ideals in the United States.

By 1910, the Rose Valley shops had been shuttered for financial reasons, but the community continued to be considered a desirable, “artistic” suburb. Arden and several imitator communities near Wilmington maintained their radical attempts at communal ownership, modeled after economist Henry George’s “single-tax” theories.

Remnants Survive

Although many art colonies eventually disbanded as coherent communities, the physical environments and traces of their organizational structures survived into the later twentieth century and beyond. For example, the Phillips’ Mill Community Association, established by New Hope–area artists in 1929, continues to exhibit art in the old mill building. Furthermore, these communities provided important precedent for the postwar studio craft movement, notably the Peters Valley colony, a community founded in a former farming village near Layton, New Jersey, in 1970 and later organized as a school of craft. Just as early twentieth-century artists tied their artistic practices to the bucolic settings and historic buildings surrounding Philadelphia, many artists and craftspeople of subsequent generations have continued to find inspiration in this landscape. The communities of New Hope, Chadds Ford, Rose Valley, and Arden, along with educational institutions like the James A. Michener Art Museum and the Brandywine River Museum of Art, carry on the artistic legacy of Greater Philadelphia and the stewardship of its important history.

Colin Fanning is Curatorial Fellow in the Department of European Decorative Arts and Sculpture at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He holds an M.A. in Decorative Arts, Design History, and Material Culture from the Bard Graduate Center. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University