Bank of the United States (First)

Essay

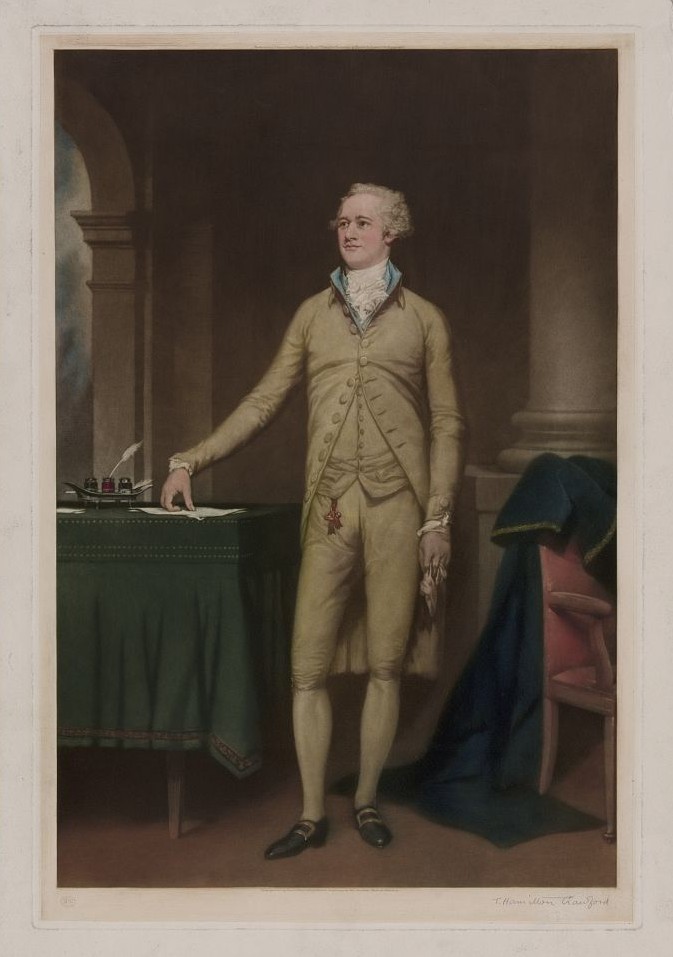

Chartered in 1791 as part of the financial and economic reform plans of Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804), the first secretary of the Treasury, the first Bank of the United States played an instrumental role in establishing the nation’s credit. Based in Philadelphia, then the national capital, the bank drew many principal investors from the region and augmented the city’s role as a center of business. The bank proved to be politically controversial and a foundational point of disagreement between developing political parties.

Hamilton’s nationally-chartered bank followed a Philadelphia precedent, the Bank of North America, established in 1781 to meet the economic challenges facing Americans during the Revolutionary War. Proposed by Philadelphia financier and superintendent of finance for Congress Robert Morris (1734-1806), the Bank of North America received a charter from Congress that provided incorporated status. Private citizens, including Philadelphia merchants and financiers, bought shares in the bank with hard money, providing the initial capital reserve for the bank to print notes and provide loans.

When Hamilton took office as Treasury secretary in 1789, economic instability and the Revolutionary War debt threatened the nation and the individual state governments. Capitalizing on those circumstances and using powers he believed the new U.S. Constitution granted, Hamilton put forth a plan that included the Bank of the United States, chartered by Congress. The bank would stabilize currency, act as a depository for and lender to the government, and raise money for the nation to pay down the war debts. Hamilton also recommended that the federal government assume the outstanding war debts of the states. By consistently paying down this debt, the nation would reestablish good faith for future loans. As an organ of the national government, the bank would also tie private citizens financially to the well-being of the United States, and those who held a stake in the war loans would likewise want to see the nation prosper to ensure their repayment.

The First Rival Political Parties

The bank immediately ignited controversy and, together with other early disputes, fueled a developing political divide that led to the first rival political parties, the Federalists and the Democratic-Republicans. Each side argued that failure to follow their policies was tantamount to abandoning the Revolution, to the ruin of the nation. Federalists, who supported the bank, tended to be urban merchants and lawyers. They supported the bank, deeming it necessary for strengthening the nation’s economy and the union in general. They believed that the Articles of Confederation had failed on both of those counts, and that the Constitution was adopted to enact just the types of vigorous national programs that Hamilton suggested. Their rivals, who often lived in rural areas and were often debtors rather than creditors, argued that the bank was unconstitutional. It would be a tool to further enrich urban elites who had stockpiled wealth during the Revolution, and increase the emphasis on volatile financial markets. Furthermore, it would do little to aid destitute veterans requiring immediate debt relief. These opponents, led by Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) in the cabinet, and James Madison (1751-1836) in the House of Representatives, also argued that by encouraging speculation and financiers, the bank would run counter to the Revolutionary principles and the virtuous agrarian ideal that best suited a republican form of government. Despite the controversy, Congress passed the legislation necessary to establish the bank, and President George Washington (1732-99) signed the bill into law, granting it a twenty-year charter to 1811.

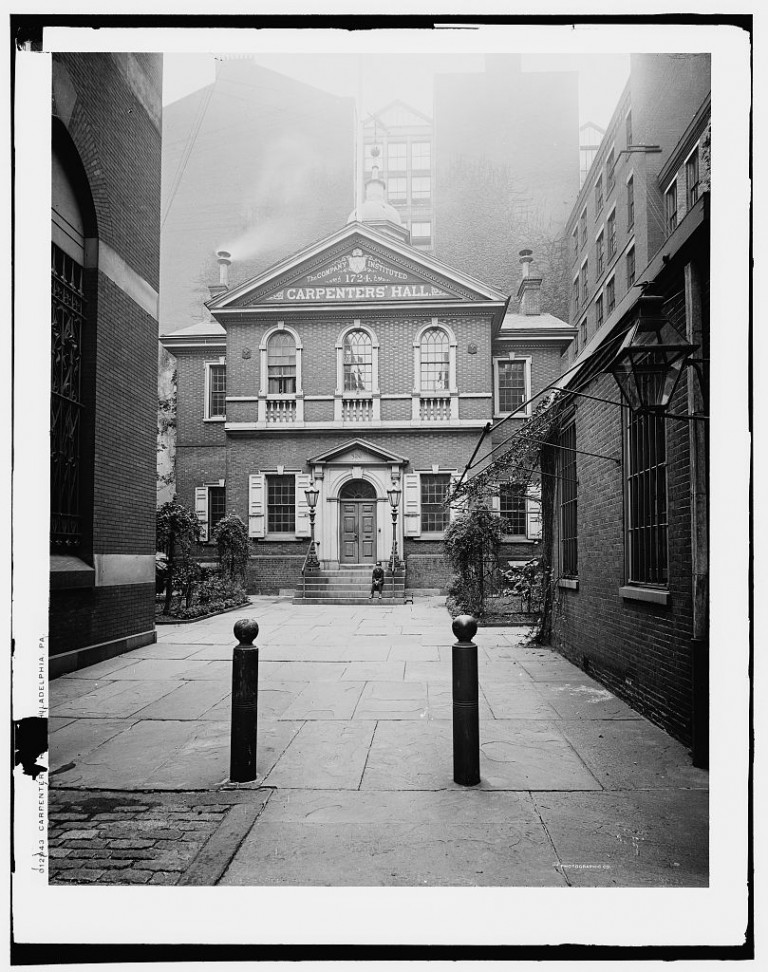

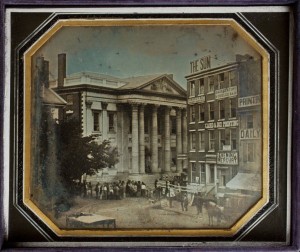

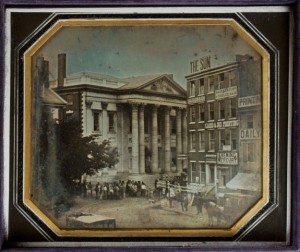

Originally headquartered in Carpenters’ Hall, the meeting place of the First Continental Congress, after 1797 the Bank of the United States moved to its own building on Third Street (later part of Independence National Historical Park). The building, an example of neo-classical architecture emulating Greece and Rome, featured a colonnaded, marble façade alluding to the ancient republican ideals that the new nation espoused.

As with the Bank of North America, the Bank of the United States drew many of its major stockholders from the Philadelphia region. Thomas Willing (1731-1821), formerly president of the Bank of North America and business partner to Robert Morris, became the national bank’s first president. Willing, Samuel Howell (1723-1807), and David Rittenhouse (1732-96), all Philadelphians, served as the bank’s first appointed commissioners. Another of Hamilton’s initiatives, the United States Mint, also located in Philadelphia, assisted the bank with its capacity to regulate the money supply. In addition to its local presence, the Bank of the United States connected Philadelphia to the nation through its branches in Boston, Baltimore, New York, and Charleston (opened in 1792); Norfolk, Va. (1800); Washington, D.C., and Savannah, Ga. (1802); and New Orleans (1805). Despite the difficulty of coordinating the far-flung branches, they assured the bank’s opponents, especially those in the South where most of the branches were established, that it would be truly national and serve more than simply Philadelphia’s merchant class.

The national controversy surrounding the Bank of the United States abated after its creation, but the partisanship it engendered continued. Within months of its incorporation, the bank, through its initial branch in Philadelphia, played a hand in the credit bubble and restriction that set off the Panic of 1792, seemingly confirming fears about economic volatility held by the bank’s opponents. In spite of that incident, by the end of the bank’s twenty-year charter in 1811, national credit was largely established and the Democratic-Republicans controlling Congress allowed the charter to expire with the assets liquidated relatively peacefully, at least in Philadelphia. The Philadelphia branch’s shares were primarily bought out by Philadelphian Stephen Girard (1750-1831), who operated the institution as a private concern, the Girard Bank. Only five years later, in the midst of depressed trade after the War of 1812 and European Napoleonic Wars, Congress instituted a Second Bank of the United States (also headquartered in Philadelphia).

The First Bank of the United States played a pivotal role in establishing the nation’s credit. It drew from the traditions of banking already present in Philadelphia during the Revolution, was supported by Philadelphia’s merchant class, and set a precedent of national banking. It contributed to the growing partisanship of the early Federal period and helped the Philadelphia region and its wealthy elite remain at the epicenter of national finance and the economy into the nineteenth century, even after the seat of government shifted to Washington, D.C.

Jordan AP Fansler grew up in Pennsylvania, is a graduate of Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, and has worked at multiple museums in Greater Philadelphia. His doctoral thesis and scholarly work focus on the relationship of citizens to their state, national, and imperial governments in the early-modern Atlantic World.

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University