Chemical Industry

By John Kenly Smith Jr. | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Since the eighteenth century, chemical or chemical processing industries have been an important part of the economy of Philadelphia and the Delaware Valley region and have reflected larger trends in the industry. The earliest chemical companies manufactured products such as sulfuric acid and white lead pigments for local consumption, while other manufacturers, such as tanners, brewers, and soap makers, also employed chemicals and chemical processing. During the nineteenth century, new industries, such as textiles, required many different types of chemicals, including dyes, soaps, and bleaches. Pharmaceutical production also became important. World War I led to the rapid expansion of local chemical production. Following the war, the American chemical industry thrived by developing many new products, especially synthetic materials. After 1980, however, industry innovation declined, growth rates slowed, and competition increased, leading the region’s largest chemical manufacturers to be consolidated on a national level.

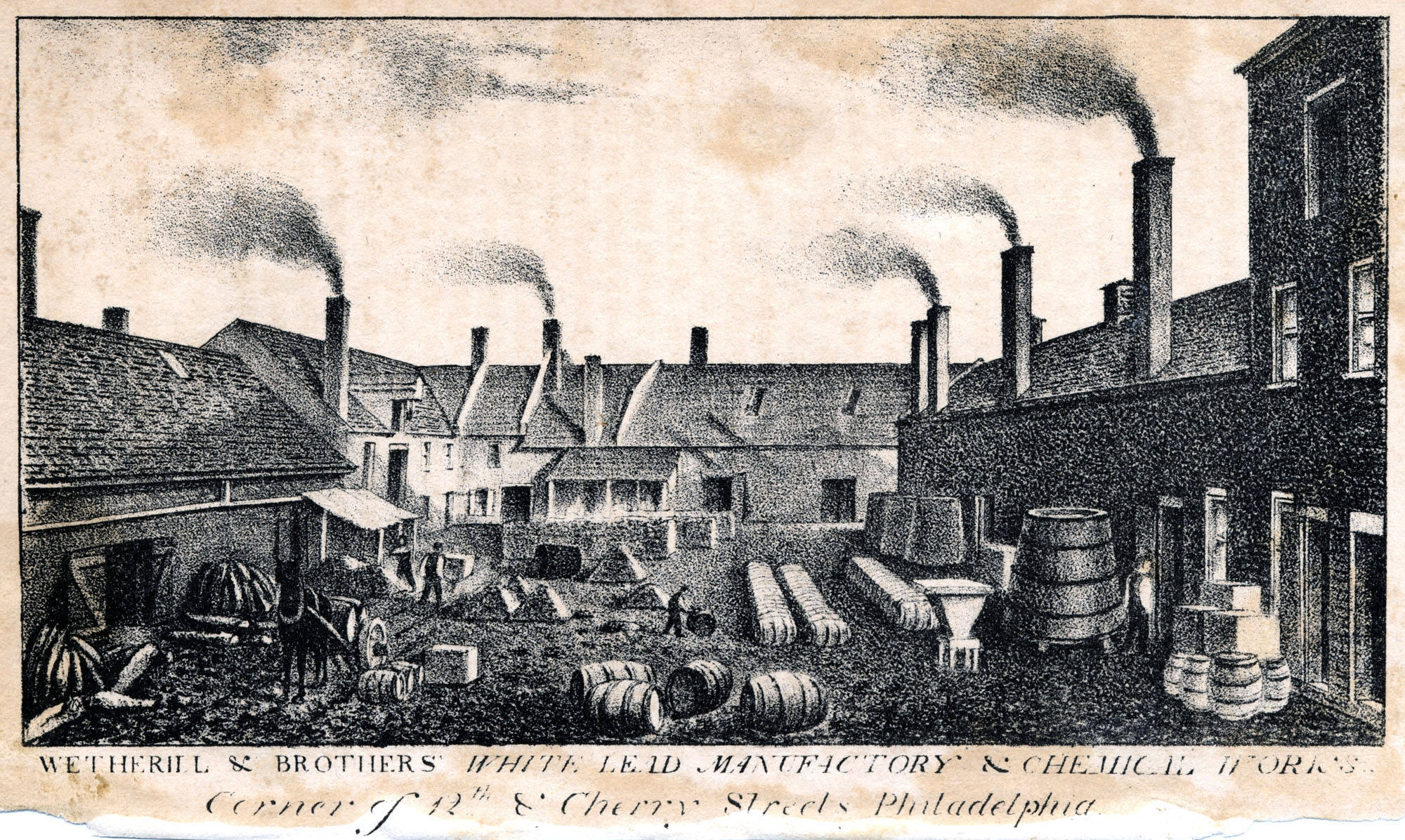

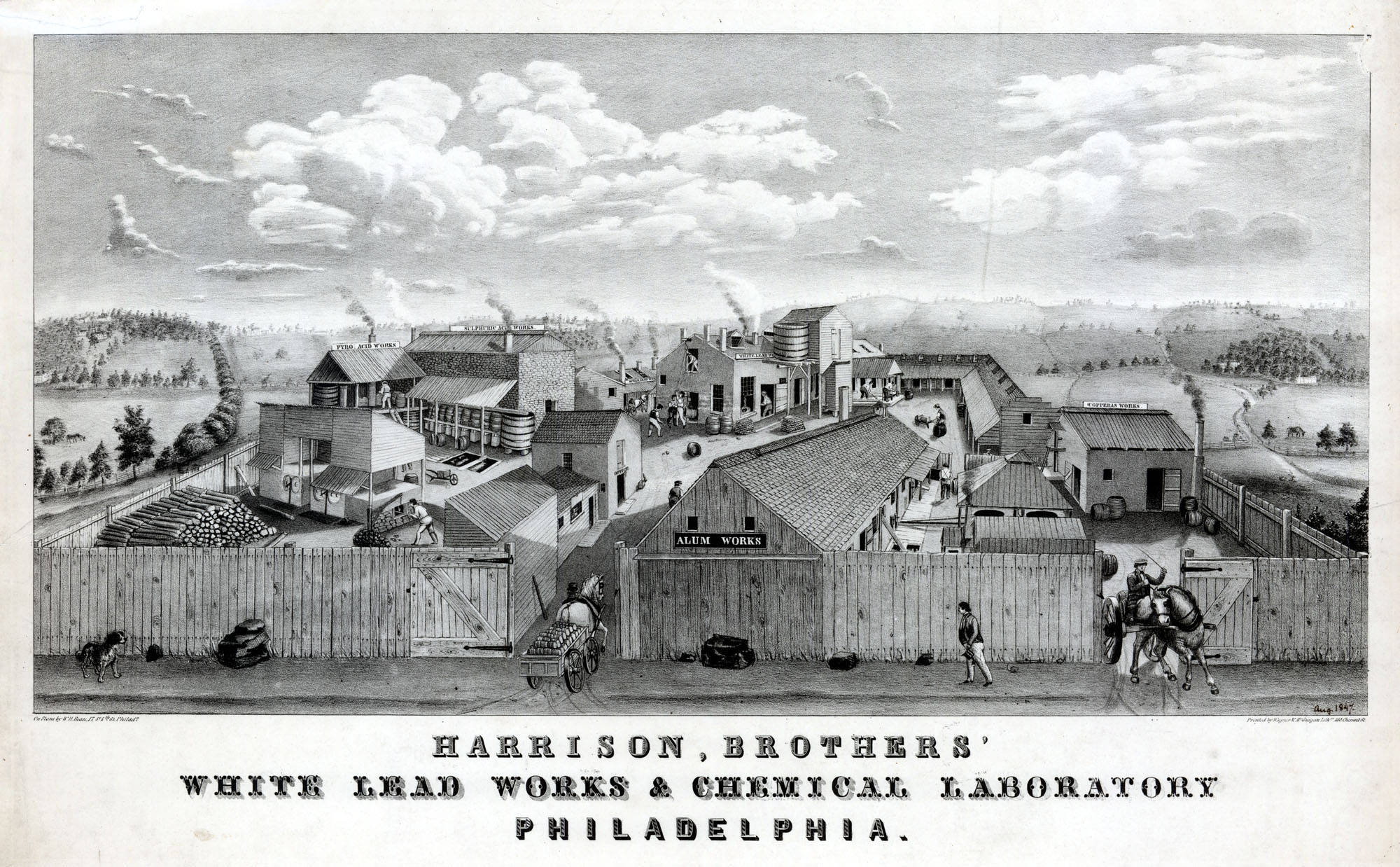

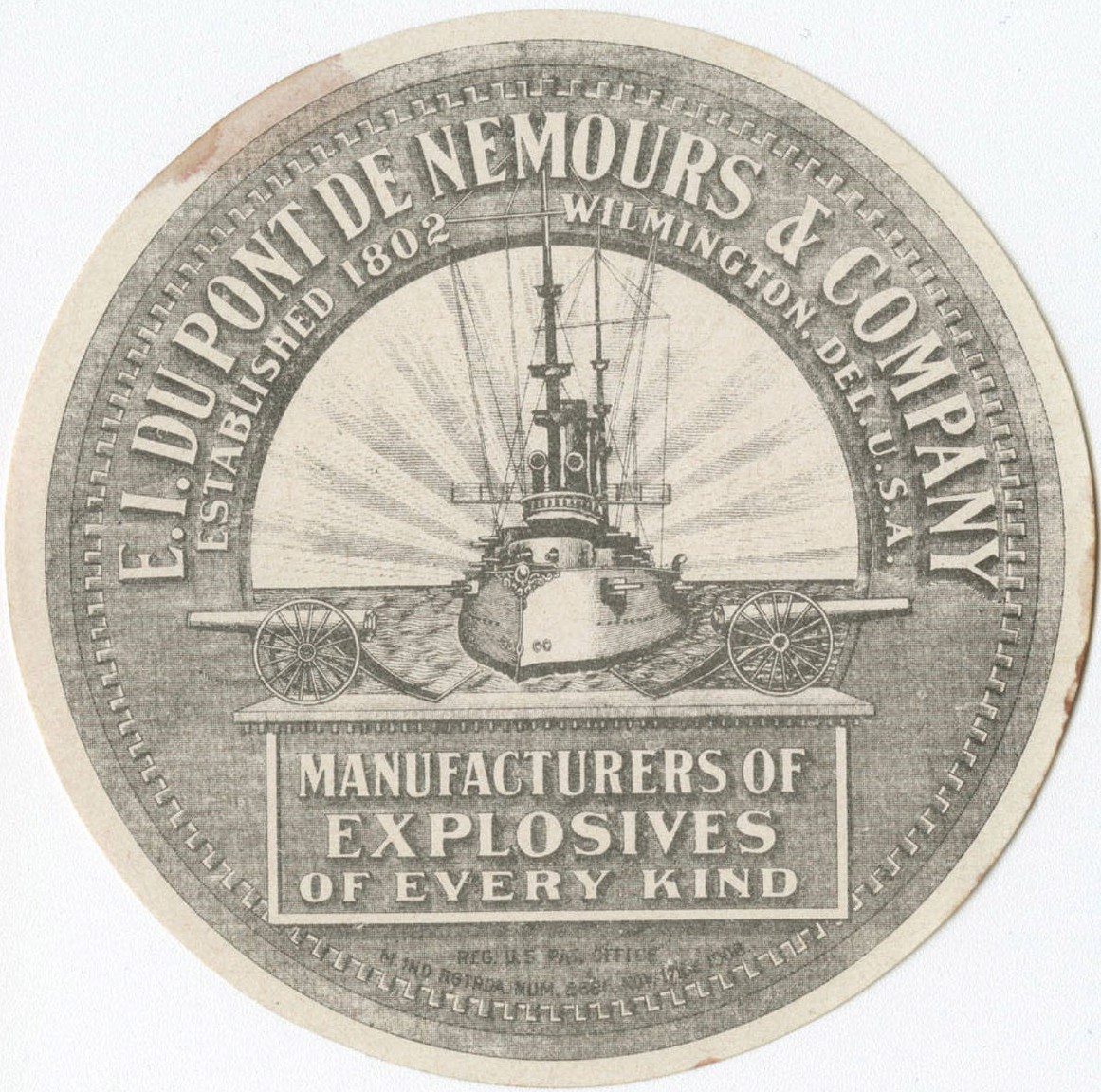

In Philadelphia, John Harrison (1773–1833) built the first chemical plant in the United States in 1793. His plant on Green Street, west of Third, produced sulfuric acid using a lead chamber process, originally developed in Europe. Sulfuric acid was the first chemical produced on an industrial scale, leading to its widespread use. In 1802, the French immigrant family led by Eleuthère Irénée duPont (1771–1834) founded the DuPont Company, which manufactured gunpowder, a mixture of charcoal, sulfur, and saltpeter, on the Brandywine River a few miles northwest of Wilmington, Delaware. Several years later, in 1804, Samuel Wetherill (1736–1816) began to make white lead pigment for paint near Harrison’s plant. When the War of 1812 disrupted trade and cut off European supplies of sulfuric acid, Wetherill began to make his own.

Soap and Sulfuric Acid

The regional chemical industry grew along with the local economy. By the start of the War of 1812, Philadelphia had twenty-eight soap and candle works, eighteen distilleries, fourteen glue factories, ten sugar refineries, seven paper mills, and six drug-making concerns. By 1830 Charles Lennig (1809–91) operated the largest sulfuric acid plant in America, located in Bridesburg. He diversified into other chemicals, and by 1859 his plant was one of the most important chemical operations in the United States. During the Civil War, the DuPont Company prospered by selling gunpowder to the Union. Later, the company diversified into the new high explosive, dynamite, and military smokeless powder. DuPont was one of 105 local chemical manufacturers to mount exhibits at the 1876 Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia.

In the twentieth century, the DuPont Company and Rohm and Haas emerged as the two most important chemical enterprises in the Philadelphia area. Rohm and Haas became a Philadelphia company in 1909 when Dr. Otto Haas (1872–1960) arrived to sell a leather tanning chemical, Oropon, which had been developed by his partner Otto Rohm (1876–1939) in Germany. After World War I, Rohm and Haas began making chemicals for Philadelphia’s leather and textile industries. In 1920, it acquired the Charles Lennig Company. In the 1930s, company researchers developed a lightweight clear acrylic polymer that was trademarked Plexiglas. Plexiglas was widely used for windows in airplanes during World War II. After the war the company continued to develop important products from acrylic polymers, such as water-based paints. In the postwar decades, Rohm and Haas became a large and profitable manufacturer of specialty chemicals.

DuPont Faces Antitrust Action

By 1912, DuPont had grown so large that the U.S. government had filed an antitrust suit, which forced the company to spin off parts of its explosives business to form two new companies, Hercules and Atlas, named after popular brands of dynamite. These companies later became diversified chemical manufacturers, which were bought by other chemical companies in the second half of the twentieth century. DuPont’s assets grew tremendously during World War I, when the company supplied the Allies and the United States with explosives. DuPont used its newfound wealth to diversify into chemical manufacture, principally by buying other firms, such as the venerable Harrison Brothers Company in 1917, which by this time made chemicals and paints at Gray’s Ferry. During the war, DuPont began a major research initiative to manufacture the dyes that the Germans had supplied before the war. To make dyes, the company built a large plant on the Delaware River at Deepwater Point, New Jersey (just north of the Delaware Memorial Bridge).

After the war DuPont continued to diversify into rayon fibers, cellophane films, and plastics. Having been one of the first American companies to establish research laboratories (early in the twentieth century), DuPont called upon its chemists to improve these products, but they soon began to invent new ones. In the 1930s researchers began a decades-long investigation of polymers (long-chain) molecules that produced, among many iconic products, neoprene synthetic rubber, nylon, Teflon polymers, Lycra spandex, Tyvek spun-bonded fabric, and Kevlar fibers. These inventions helped to make DuPont an extremely prosperous company, a bulwark of the Delaware Valley economy, employing tens of thousands of people in several local plants, but mainly in management, research, and engineering.

The Philadelphia area also was well-represented at midcentury by two industries closely related to chemicals: oil refining and pharmaceuticals. There were five large refineries in the Delaware Valley, making it the second only to Houston, Texas, in output, and the city also hosted four major drug manufacturers.

Late Twentieth-Century Slowdown

Beginning in the 1980s, the chemical industry generally began to experience a decline in innovation, slowing growth, and shrinking profits. Rohm and Haas’s performance, following these trends, deteriorated significantly. In response, it sold off its Plexiglas business and acquired a company that made chemicals for the semiconductor industry. In 2008, the Michigan-based Dow Chemical acquired Rohm and Haas. DuPont survived by shifting its focus to pesticides and seeds. However, competition in this field led the company to a merger effort with Dow Chemical, its longtime competitor, in 2015. By the early decades of the twenty-first century, the chemical industry had been radically reorganized through numerous mergers and acquisitions.

Chemical production began in Philadelphia in the late eighteenth century to serve nearby manufacturers in what soon would become one of America’s major industrial cities. By the middle of the nineteenth century, Delaware Valley companies, notably DuPont, were taking advantage of railroad transportation to serve larger markets. In the twentieth century, the regional chemical industry served national and international markets, expanding to become a significant contributor to the local economy. In the last quarter of the century, however, the chemical industry globally matured, leading to a decline of its importance locally.

John Kenly Smith Jr. teaches history at Lehigh University. He specializes in the history of technology and is coauthor with David A. Hounshell of Science and Corporate Strategy: DuPont R&D, 1902–1980. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University