Civil Defense

By Sarah Robey

Essay

Because of Greater Philadelphia’s position as a political, cultural, and economic hub, the region’s residents have often found their daily lives deeply affected by times of national crisis. Civil defense, generally defined as local voluntary programs designed to protect civilian life and property during times of conflict, has taken many forms: militia, home defense, civilian defense, civil defense, and in the early twenty-first century, emergency response. As the nature of conflicts changed, so too did residents’ roles in home-front defense, from colonial-era militiamen to the sandbaggers who confronted coastal storms.

In the earliest days of European settlement in the Delaware Valley, colonists formed militias of able-bodied men to guard their settlements against other imperial powers, Native Americans, and pirates. However, by the time of Pennsylvania’s colonial charter in 1681, militia practices ran counter to the pacifist tenets of the region’s Quaker leadership, and militias mostly disbanded. Neighboring New Jersey and the Lower Counties of Delaware, however, continued to maintain permanent volunteer militias to be at the ready in times of crisis. By the middle of the eighteenth century, noting Pennsylvania’s inability to protect itself, Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) was instrumental in mobilizing Philadelphians to join “associated companies,” local voluntary defense groups. When the Revolutionary War broke out, Philadelphia’s associated companies and the Delaware Valley’s regional militias proved difficult to integrate into the Continental Army. In the first years of the war, state legislatures—including that of the formerly pacifist-minded Pennsylvania—passed legislation making militia service compulsory for all white men of fighting age, thereby streamlining military organization.

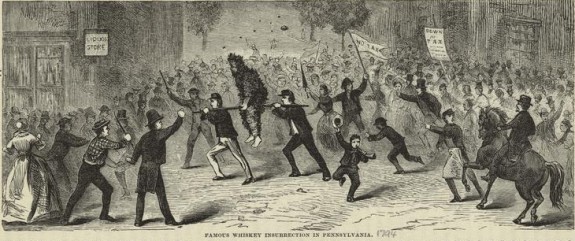

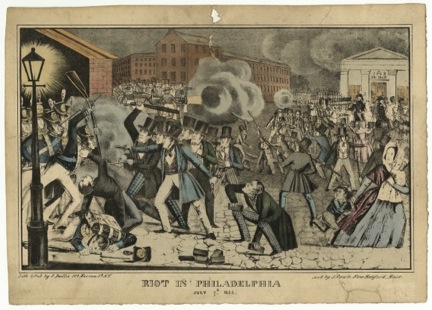

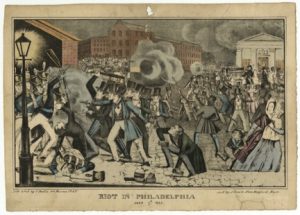

Like other states and cities in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Philadelphia region relied on local militias to preserve public safety during both peace and war. Often, the urgency of emergencies blurred the distinction between militia volunteers, police forces, and those enlisted or drafted into the armed services. As such, civil defense and active defense—or military defense—were often one in the same. In addition to participating in the Revolutionary War, Philadelphia-area militias played an integral role in smaller conflicts in the Early Republic, including the Whiskey Rebellion (1791-94), Fries’ Rebellion (1799-1800), the War of 1812, and the Nativist Riots in the Kensington and Southwark sections of Philadelphia (1844). However, in the relative peace of the antebellum years, militias also were important civic and social organizations, with individual companies frequently composed of men belonging to a particular trade, ethnicity, religion, or political party. Muster days—events held for roll-call and training—often included parades, games, and patriotic celebrations.

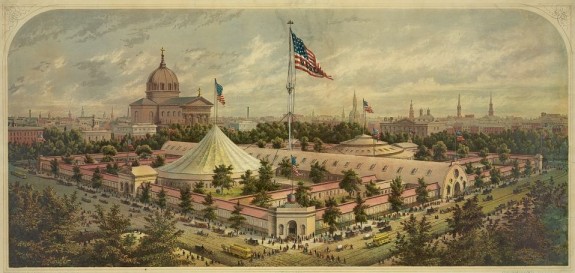

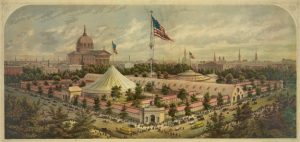

During the Civil War, Philadelphia became central to the Union’s production effort, but invasion threatened the city only briefly when the Confederate Army led by Robert E. Lee (1807-70) entered Pennsylvania in June 1863. Fearful that Lee would march to Philadelphia, volunteer groups rushed to construct physical barriers to defend the city. However, the works projects did not last long; the Union’s victory at Gettysburg ended the immediate threat to Philadelphia. Still, throughout the war, Philadelphian civic organizations such as the Union League called for participation in home guards and home defense groups as part of Philadelphians’ patriotic duty. Generally, these all-male brigades and regiments assumed similar functions to past militias. Women and families contributed to the war effort through charitable efforts, such as Philadelphia’s 1864 Sanitary Fair, or women’s auxiliaries.

Twentieth-Century Civilian Defense

The United States’ early twentieth-century conflicts placed the Delaware Valley in an integral position in war industry and national transportation networks. As the Philadelphia home front became deeply involved in both World Wars I and II, the changing nature of war made new demands on Philadelphia’s civilian defense. New military technologies from both wars, including airplanes, submarines, and missiles, expanded the reach of a potential enemy attack to include the American mainland, beyond the geographic boundaries that once offered Philadelphia protection during ground or naval war. As modern war increasingly threatened the homeland, many Philadelphians grew concerned that the region could be a target.

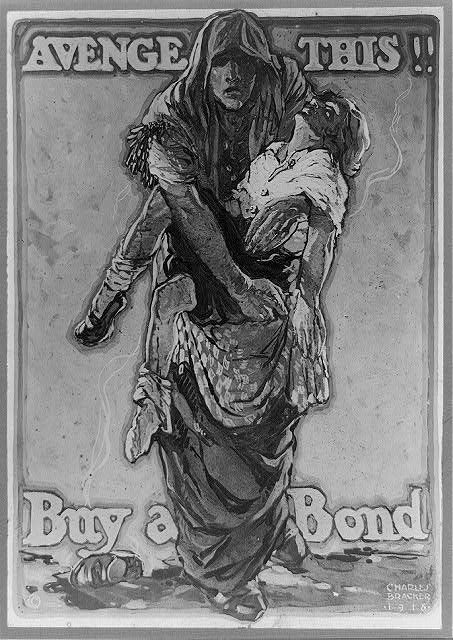

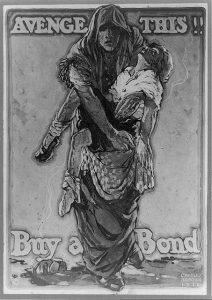

During World War I, some Philadelphian civilians joined anti-sabotage programs designed to maintain a watchful eye on suspicious activity, especially in military industrial plants. But civilian defense during the Great War was primarily a mobilization effort to support the military, including bond drives for Liberty Loans and draft rallies. Echoing Civil War home guards, citizens enlisted in organizations such as the Philadelphia Home Defense Reserve to assist local officials in the event of a home-front crisis. But the United States’ brief involvement in the war cut short the tenure of civilian defense activities, and most programs were dismantled shortly after the war concluded.

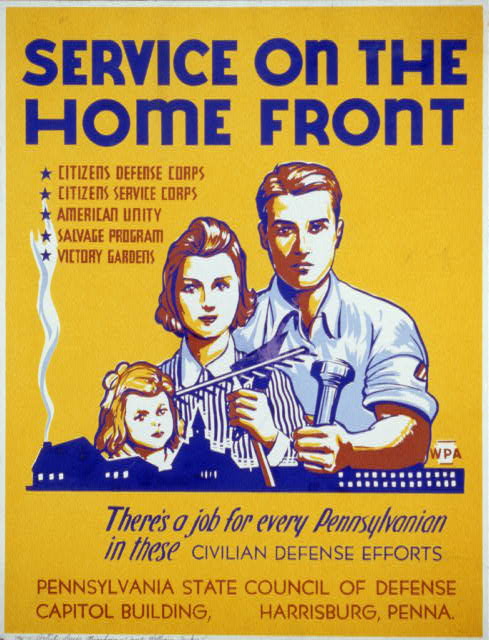

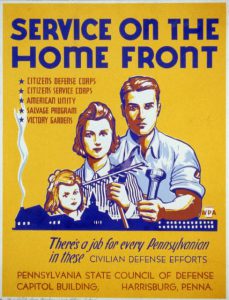

After the United States entered World War II, however, the region revived and strengthened many of its earlier civilian defense programs. While residents of the Delaware Valley once again participated in bond rallies, food rationing, and anti-sabotage campaigns, the preparations for an attack took on a more militarized focus. The Philadelphia city government, newspapers, and civic organizations printed millions of informational pamphlets that included air raid information, instructions for building shelters, and basic first aid techniques. Periodic blackout drills required residents to turn off outdoor lighting, cover building windows with dark curtains, and dim automobile lights in order to disguise the city from potential attacking aircraft. Citizens across the region learned to identify enemy planes, and along the region’s rivers and coastlines, residents volunteered to take shifts as submarine spotters.

Cold War Civil Defense

After the end of World War II, the region’s civilian defense underwent another transformation. Nuclear weapons, used by the United States against Japan at the end of the war and soon after acquired by the Soviet Union, presented a new threat to public safety. The power of nuclear weapons exceeded the destructive capabilities of earlier weapons of war by several orders of magnitude, endangering more civilians than ever before. Because of the Philadelphia area’s importance in industrial production, its critical transportation infrastructure, and its large metropolitan population, the region rushed to find ways to prepare and defend itself from attack. While postwar Americans looked to civilian defense methods from earlier eras, many saw activities such as victory gardens and bond rallies as anachronistic and ineffective for the Atomic Age. In Philadelphia and across the country, Cold War civilian defense became known as “civil defense” in part to distance new strategies from the legacy of outmoded programs.

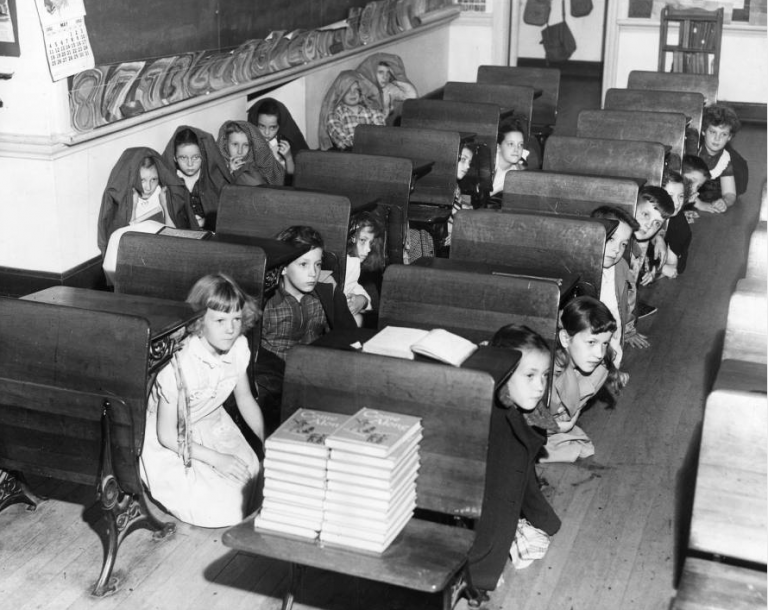

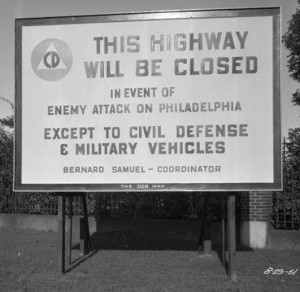

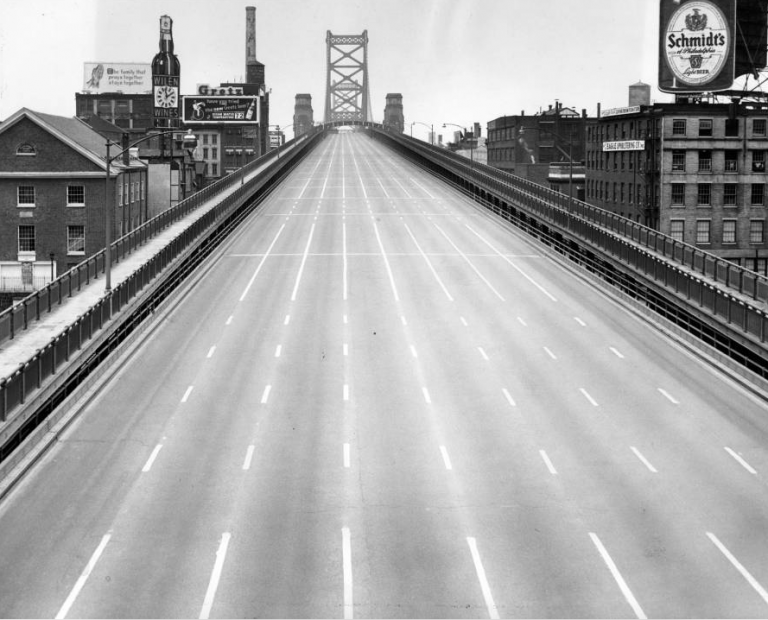

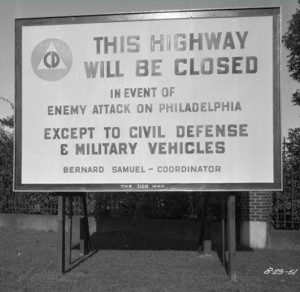

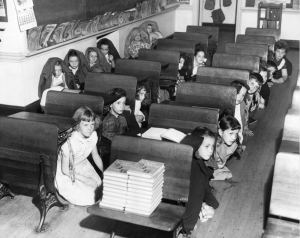

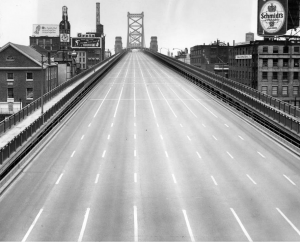

As in many threatened American cities, Philadelphia’s leadership took an early active role in local civil defense planning. In 1951, Mayor Bernard Samuel (1880-1954) established the Philadelphia County Civil Defense Council, responsible for hosting educational programs and organizing a military-style chain of command to connect city residents with block wardens, neighborhood coordinators, city offices, and civil defense officials. Throughout the 1950s, the council ran citywide drills designed to give civilians an idea of the kind of destruction they could expect, and the actions they would need to take should a real attack occur. Notably, during 1954’s Operation SCRAM (Survival of our Citizens depends on Cooperation, Alertness, and Mobility), more than twenty-five thousand Philadelphians evacuated the blocks closest to City Hall to a muster point on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. With the assistance of federal civil defense funds, cities, counties, and states built a system of fallout shelters—identified by ubiquitous yellow and black signage—in many buildings, including Philadelphia’s City Hall and public schools.

One of the most challenging aspects of the Philadelphia area’s Cold War civil defense efforts, however, was the relationship between its cities and surrounding towns and counties. Should an attack occur, the entire Delaware Valley region would need to mobilize to deliver supplies and transport millions of evacuees. Successful civil defense plans thus relied on coordination between the cities of Philadelphia; Trenton and Camden, New Jersey; and Wilmington, Delaware, as well as hundreds of towns and several counties. Because every municipality had different civil defense needs, and every state had its own civil defense legislation, regional and interstate coordination was a logistical problem that officials never fully resolved.

In the end, Philadelphia’s Cold War-era civil defense fell victim to the changing city politics of the postwar period. The Civil Defense Council had difficulty defending its budget and usefulness to reform Democrats, especially as nuclear weapons technology advanced well beyond the capacity of civil defense strategies. Moreover, civil defense was a hard sell to Philadelphians, who balked at rehearsing for such catastrophic war in a time of peace. By the late 1960s, facing significant public apathy and ridicule from critics, the region’s civil defense activities had declined drastically and emergency planning energy was redirected toward preparation for peacetime crises. In 1972, Philadelphia’s Civil Defense Council merged with the Fire Department to become the Office of Emergency Preparedness (OEP). The OEP relied on regional volunteers and local relief organizations during extreme weather, industrial accidents, and other disasters to assist in preparation and recovery efforts.

Throughout its history, Greater Philadelphia has relied upon its citizens to help keep the region safe. Whether compulsory or voluntary, popular or unpopular, civil defense has shaped the region’s politics and culture. Although the nature of crises and war has changed significantly since the seventeenth century, civil defense has remained a consistent part of civic life in the Philadelphia area.

Sarah Robey is a Ph.D. candidate in History at Temple University, where she studies American nuclear culture. She has been a fellow at the Philadelphia History Museum, the National Museum of American History, and the National Air and Space Museum. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Former N.J. governor Whitman urges EPA to step up safeguards against chemical attack (WHYY, June 12, 2012)

- Can private cameras protect Delaware from a terrorist attack? (WHYY, July 28, 2015)

- Reality check on refugee panic: Suspected terrorists in America are free to buy guns (WHYY, November 20, 2015)

- No terrorist connection found in ambush of Philly cop, but FBI probe continues (WHYY, January 14, 2016)

- Exhibition of Cold War art is relevant in today’s political climate (WHYY, March 31, 2016)

- With the rise of lone-wolf attacks, N.J. aims to catch terrorists before they become radicalized (WHYY, June 13, 2016)

Links

- Nuclear Apocalypse at 12th & Arch (PhillyHistory Blog)

- When We Were Ready (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Benjamin Franklin's Plain Truth (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- Operation Scram Called Success in Philadelphia (Google News Archive)

- Civil Defense Pamphlets: An Historical Perspective (Free Library of Philadelphia)

- Philadelphia in the Civil War (LaSalle University Digital Collections)

- The Philadelphia Homefront: Rallying the Troops (Library Company of Philadelphia)

- South Philadelphia Women's Auxiliary Liberty Loan Committee records (pdf, Historical Society of Pennsylvania)