General Strike of 1910

Essay

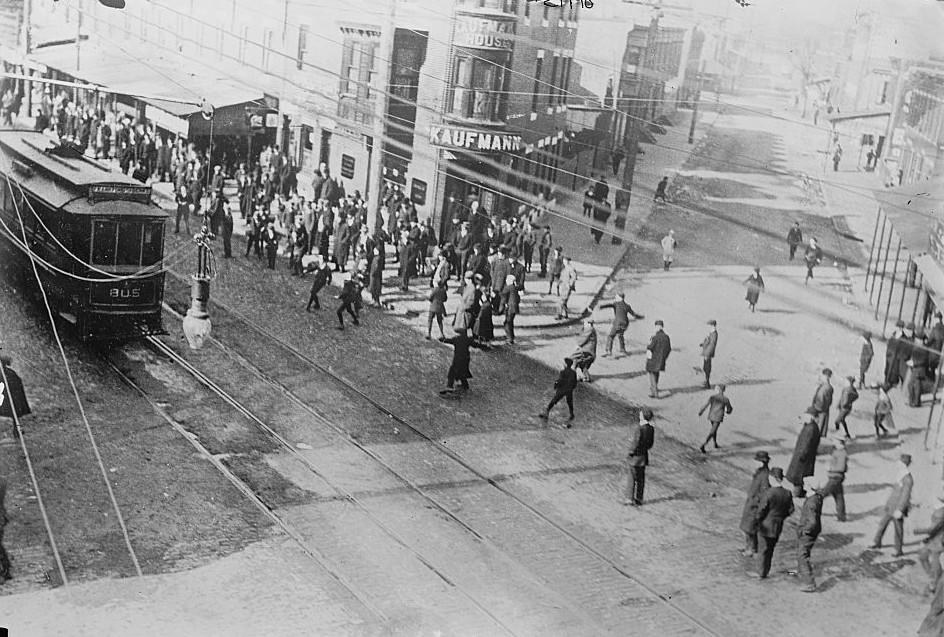

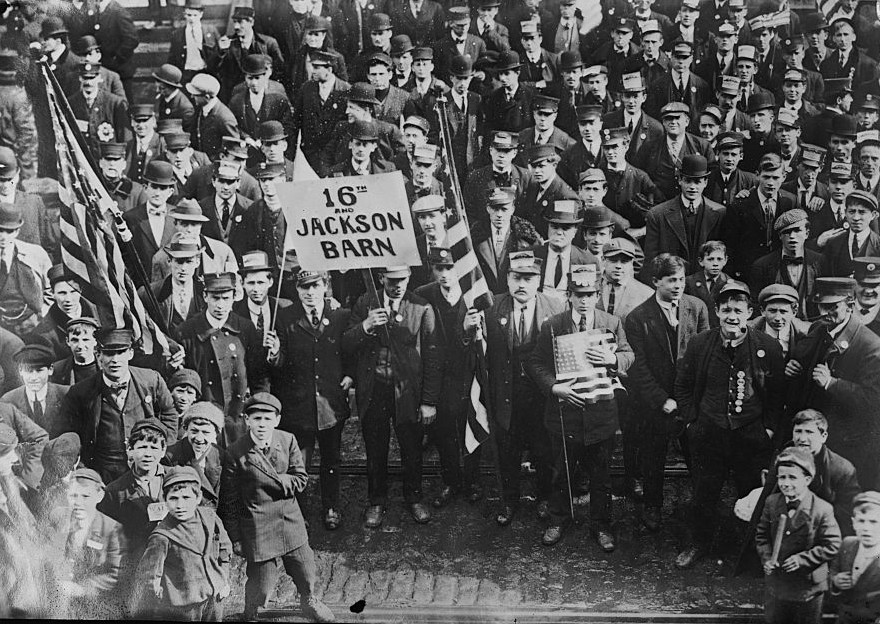

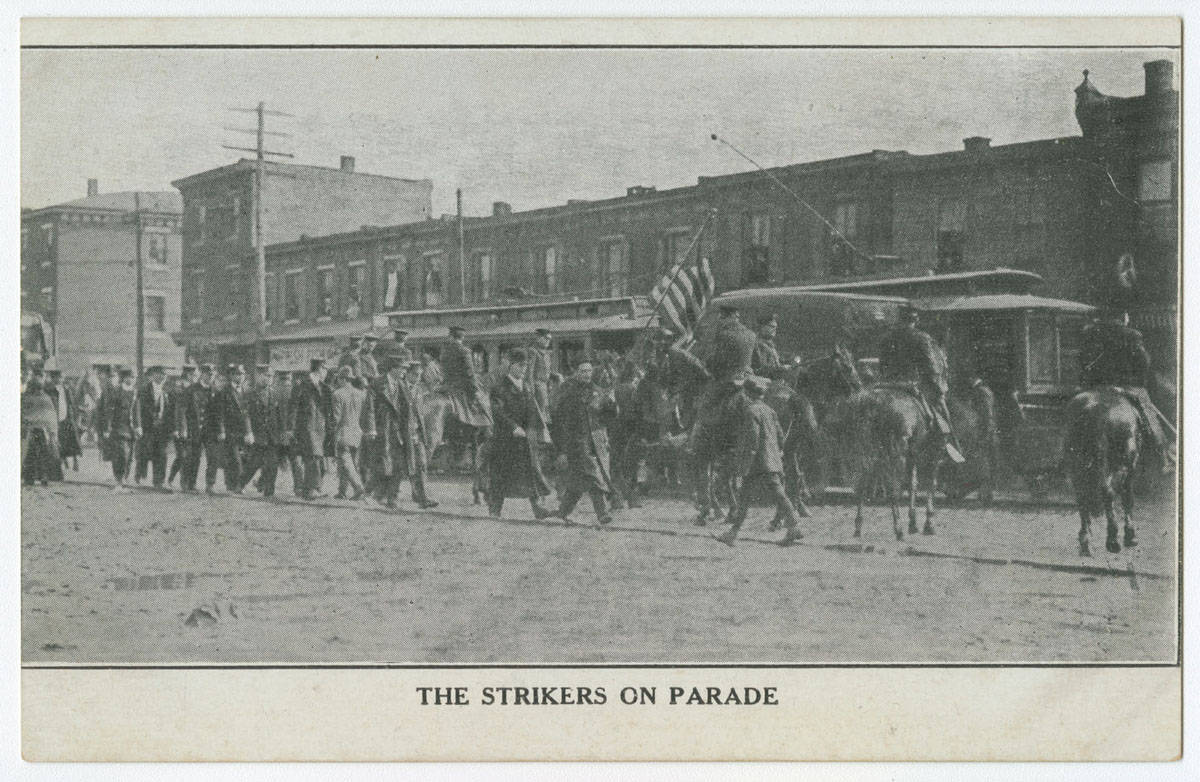

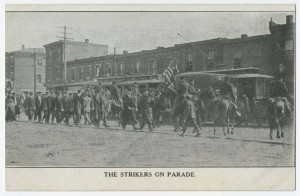

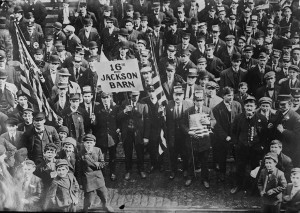

On March 5, 1910, between 60,000 and 75,000 workers complied with the Central Federated Union’s call for a general strike in solidarity with the striking streetcar workers employed by Philadelphia’s Rapid Transit Company (RTC). Business and political elites feared that the strike would spread to other parts of Pennsylvania and to cities where workers had pledged their support, including Newark, San Francisco, and New York. The general strike, which lasted until March 27, grew to an estimated 140,000 people. The strike saw loss of life and property in violent standoffs between strikers, strikebreakers, and police officers, and spoke to widespread dissatisfaction with labor conditions and municipal corruption in Philadelphia.

The general strike was precipitated by an escalating dispute with RTC. The company had laid off 173 organized workers (who had unionized under Local 477 of the Amalgamated Association of Street and Electric Railway Employees of America) in anticipation of the February municipal elections—thus delaying a strike and helping Republicans sweep the municipal elections. RTC admitted to discriminating against Amalgamated members in favor of “loyal” workers, and, in response, 6,000 workers called a strike for January 18.

The walkout was the latest in a succession of strikes in Philadelphia’s transit industry, including strikes in 1895 and 1909. The public transportation system had been mired in corruption that implicated both private interests and the city’s Republican political machine (the director of public safety was a large stockholder in RTC). Incorporated in 1902 as a long-term leaseholder of nearly all of Philadelphia’s railway lines, the company had renegotiated its contract with the city in 1907. RTC agreed to pay a fixed fee in return for relief from its obligation to repair roads and clear snow, while also securing a monopoly on all future railway projects through 1957. As a result, service worsened and the city took on a tremendous fiscal burden.

Widespread Dissatisfaction

By the time of the 1910 strike, press reports had documented widespread public dissatisfaction with RTC, which had discontinued transfers and discounted strip tickets and initiated fare hikes, among other service issues.

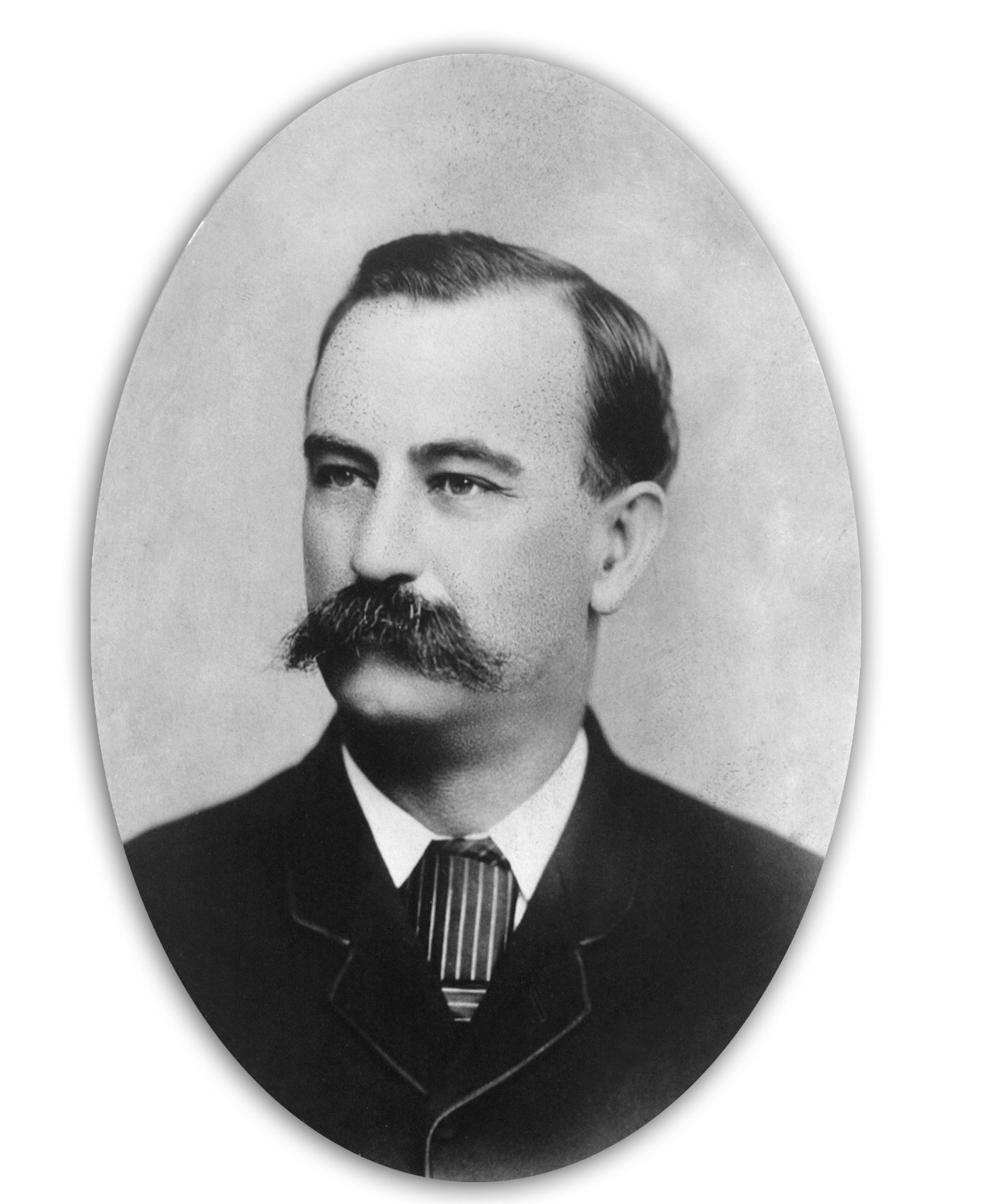

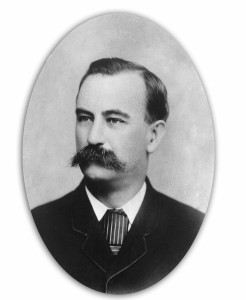

Strike organizers saw the company’s disrepute as key to the strike’s chances for success: Leaders tied RTC and the administration of Mayor John E. Reyburn (1845-1914) to lawlessness, violence, and anarchy, in opposition to justice-seeking workers and residents of Philadelphia.Organizers saw the strike as a local stage for broader conflicts between organized labor and capitalist interests. In order to appeal to nonunionized workers and the general public, leaders discouraged radical “outsiders” from infiltrating the strike and any violence other than destruction of RTC property.

The general strike was a tactical escalation in response to RTC’s unwillingness to arbitrate. The key disagreement between RTC and Local 477 was the exclusive right of the union to organize RTC workers, which would enable membership growth and bargaining power, as had been achieved by transit workers in San Francisco, Detroit, Cleveland, and Pittsburgh. RTC knew this, and was committed to maintaining an open shop to prevent a wage increase. RTC would not surrender on what it considered “fundamental and inalienable rights” as a corporation, namely: to not be subjected to any outside organization and to be able to fire employees at will.

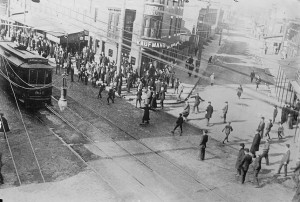

Anticipating a strike, in January RTC hired and trained nearly 1,000 on-call workers to be used as strikebreakers. During the strike, RTC officers brought in additional workers from Boston, New York, Baltimore, Washington, Norfolk, Richmond, Reading, Wilmington, Cleveland, St. Louis, and smaller towns. RTC built dormitories at its nineteen depots to house these new workers, with a commissary who directed hundreds of cooks and other staff. Further, the Philadelphia police acted as on-call private security for RTC, and emergency police stations were constructed at key RTC depots. At the height of the strike, RTC fed and housed over 7,000 strikebreakers and police officers.

Union Organizers Arrested

During the strike, Philadelphia police arrested high-ranking union organizers and sympathy strikers—fifty percent ofwhom were under the age of 18— being authorized to “storm” strikers with guns and batons. Newspapers reported violence and sabotage to render streetcars inoperable, as well as retaliation by strikebreakers who shot into crowds and accelerated along their routes, causing several bystander fatalities. Newspapers reported that at least two young children lost life and limb from the streetcars, and that as many as ten strikers and bystanders were killed by gunfire from strikebreakers and police.

Though the general strike ended on March 27, the streetcar workers remained on strike until April 19. After three months, RTC finally agreed to a wage increase, the rehiring of strikers within three months (though stripped of seniority), and mediation of the initial 173 union-targeted firings. Overall, the nine-week strike cost RTC $2,395,000 and the city millions more, and 3,400 workers returned to work having won some of their demands.

The strike had organized workers across industries in opposition to the public-private alliance between the police, the Reyburn administration, and RTC. It convinced RTC and the city that “rioting cannot be effectively suppressed except by radical measures”—namely, police officers’ liberal use of revolvers and clubs—and compelled the city and elite reformers to push for a strengthened police force and structured intervention to prevent juvenile delinquency. Though the strike did not achieve its central demand—exclusive union recognition— it paralyzed the city, garnered tremendous solidarity, and demonstrated the capacity of labor to organize across industrial lines.

Julianne Kornacki is a doctoral student in political science with an interest in the history of municipal and neighborhood politics in Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Delaware fast food workers on strike (WHYY, August 29, 2013)

- Will the clock 'strike' midnight on SEPTA service? (WHYY, March 14, 2014)

- Assessing impact of SEPTA strike on outlying suburbs (WHYY, June 13, 2014)

- No deal: SEPTA Regional Rail workers announce strike (WHYY, June 14, 2014)

- No SEPTA strike Monday (WHYY, October 24, 2014)