Gothic Literature

Essay

From the early nineteenth century onward, Philadelphia spawned an abundance of mysterious tales starring shadowy strangers, fantastic happenings, and deadly conspiracies. Prominent genre writers including Charles Brockden Brown (1771-1810), George Lippard (1822-54), and Edgar Allan Poe (1809-49) made the City of Brotherly Love the birthplace of American gothic literature.

Although the gothic arguably reached its first literary high point in the works of Charles Brockden Brown in the early 1800s, its prehistory in Philadelphia dates to the 1790s. Books such as Charlotte Temple (1791) and Rebecca (1792) by Susanna Rowson (1762-1824), though not considered gothic per se, already presented readers with many characteristic themes of the genre (such as vivid depictions of madness and adultery). Even William Bartram (1739-1823) in his famous travelogue of 1791 often lapsed from scientific verbiage into a much darker style, casting, for instance, Floridian crocodiles as lurking monsters with smoke bellowing from their nostrils.

Although the 1796 St. Herbert (published and taking place in New York) is generally considered to be the first gothic novel of the early American republic, Philadelphian Charles Brockden Brown’s Wieland (1798) was undoubtedly the most influential. While novels like Julia and the Illuminated Baron (1800), by Sally Barrell Keating Wood (1759-1855)—allegedly penned before Wieland—adopted European-style gothic plots, Brown proclaimed his novel to be an “American tale” and rooted the genre firmly in the United States. Wieland set the stage for what the gothic in the New World would be about: the perils of wilderness, the problematic indebtedness of the young democracy to old Europe, and the repressed legacies of war, colonization, and slavery.

Wieland tells the story of members of a German family living on a large estate by the Schuylkill River who—after the spontaneous combustion of the father—are haunted by ghostly voices that drive them to insanity, murder and, ultimately, flight to Europe. The tensions that the characters embody between European culture and American lands, violent past and republican present, and bucolic enclosure and untamed wildness remain unsettled—even after the novel’s convoluted plot is resolved. While the colonial past of Pennsylvania only plays a subliminal role in Brown’s first book, his later Edgar Huntly (1799) addresses it head-on: The spectral hints about the dispossession of native peoples that appeared Wieland become fully materialized. In trying to resolve a vicious murder, the eponymous narrator discovers a system of dark caves (a trope that Poe’s 1842 story “The Pit and the Pendulum” revisited) below Philadelphia. Becoming lost in this rocky subconscious, Huntly discovers bands of native peoples intent on getting revenge for the injustices of the past. In the violent conflicts that ensue, the novel again and again returns to a fundamental question: How can one inherit land if it was acquired through crime?

Orphans and Malicious Parent Figures

In the decades after Benjamin Franklin’s death in 1790, the Philadelphia gothic of Brown and his contemporaries negotiated the conflicting legacy of Republican values and the monarchic cultures of Europe. Rivaled perhaps only by the Disney movies of much later times, these novels are largely populated by either orphans or malicious parent figures. Many of Brown’s characters lose or have lost their guardians: The title character in Laura (1809) by Leonora Sansay (1773-?) succumbs to seduction after her parents’ death while the main protagonist in Kelroy (1812) by Rebecca Rush (1779-1850) is ultimately driven to illness and death by an evil, scheming mother. In the shadow of the influential image of American independence as akin to a child breaking away from tyrannical parents created by Thomas Paine (1737-1809) in Common Sense (1776), gothic authors began to expose how frail and conflicting these lines of separation could be. In the age of industrial capitalism and urban squalor, they seem to sense a resurgence of a monarchical past that the young republic hoped to leave behind—and what better place to examine this than in the birthplace of the Continental Congress?

With Robert Montgomery Bird, a local physician turned writer, the Philadelphia gothic found its second best-selling author. Often advancing themes from Brown—such as his vivid depictions of anti-Native American violence—Bird turned from setting his novels in Mexico (Calavar, 1834; The Infidel, 1835) to writing gothic tales placed in and around Philadelphia. Among these, Sheppard Lee (1836) and Nick of the Woods (1837) remain his most successful publications. Where Brown’s fictions are somber and highly complex, Bird introduces satire into the Philadelphia gothic. From the conundrum of an Indian-killing, pacifist Quaker in Nick of the Woods to parodies of the two-party system (Whigs vs. Democrats) in Sheppard Lee, Bird playfully exposes the often self-contradictory nature of Philadelphia society in the age of Jacksonian democracy.

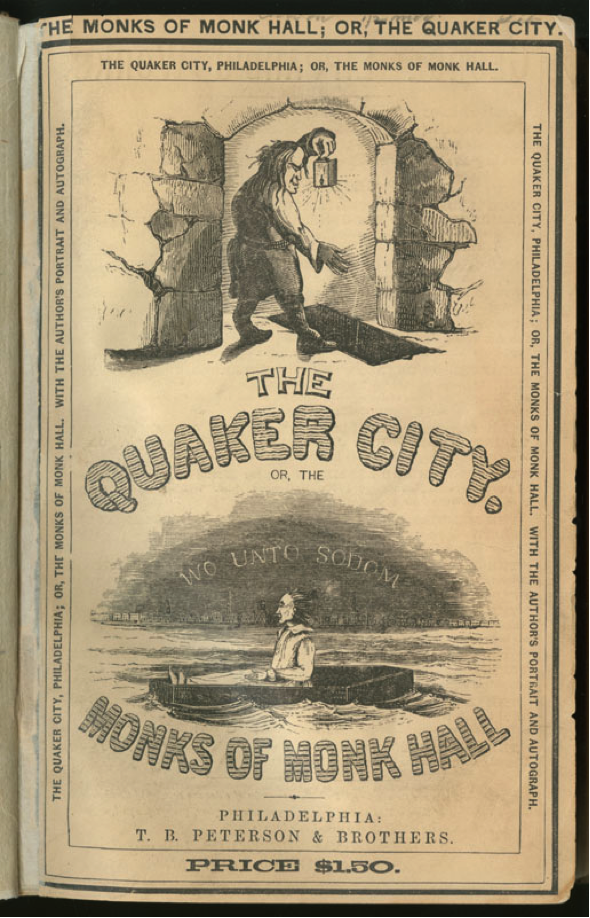

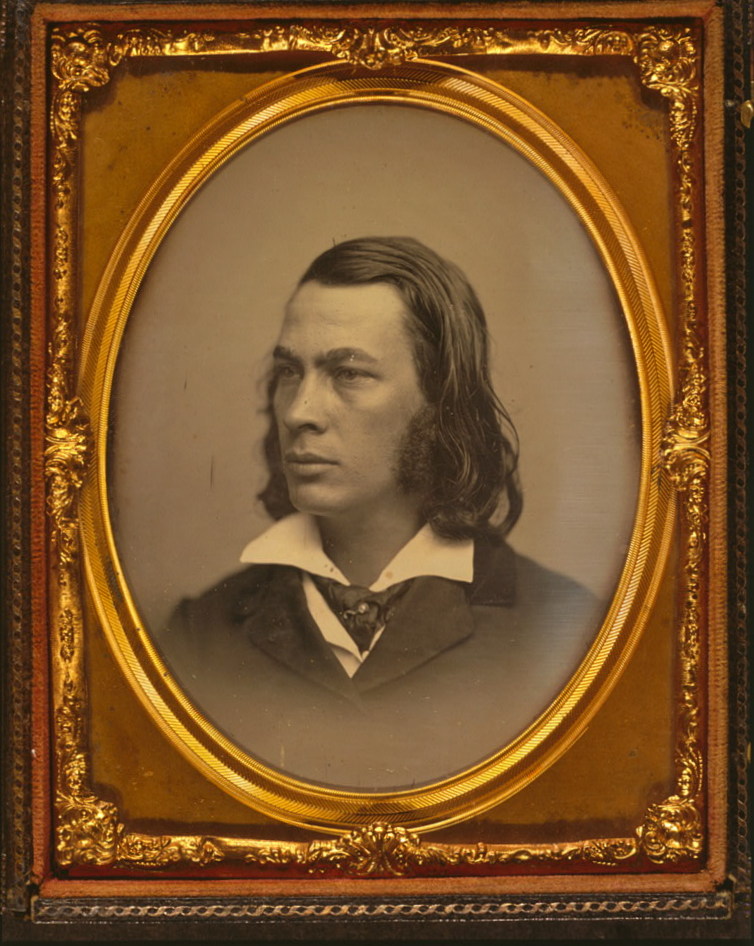

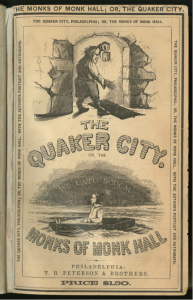

As comments on Philadelphia life, books like Bird’s Sheppard Lee or Brown’s Arthur Mervyn (1799), take their readers from the wilderness surrounding the city to the city itself. In contrast to the revolutionary past, these fictions portray the city as a metropolis of disease and crime, populated by thieves, beggars, and assassins. Bird’s fantastic tale of the body-swapping Sheppard Lee (1836) satirizes a society of empty ambition and pseudo-aristocratic pomp. George Lippard takes a step farther. His novel The Quaker City, or The Monks of Monks Hall (1845)—dedicated to Brown—depicts the city as a hotbed of sin ruled by a decadent elite who meet in an underground brothel to orchestrate their exploitation of Philadelphia. Reveling in seduction, drinking, gambling, and murder, this elite of Chestnut Street create a new Sodom behind a façade of republican morality. Lippard’s subterranean rulers of Philadelphia turn republican values on their head: Accompanied by the ringing of the bell of Independence Hall, journalism becomes blackmail, justice can be bought, and priests try to defile their own offspring.

![George Lippard, head and shoulders portrait, facing left]](https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/lippard-002-239x300.jpg)

The most successful American publication before Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), Lippard’s graphic indictment of Philadelphia culminates in an apocalyptic dream-vision of hordes of Black and white slaves lining the streets while the new aristocracy of the Quaker City abolishes democracy and crowns a new king for the United States. The fame of Lippard’s novel spawned a boom of “mysteries” set in Philadelphia, such as the anonymously published Mysteries of Philadelphia (1848), Aristocracy, or Life in the City (1848) by Joseph A. Nunes (c. 1820-c. 1905), Mysteries and Miseries of Philadelphia (1854) by George Thompson (1823–c. 1873), and The Homeless Heir, or, Life in Bedford Street (1856) by “John the Outcast.” All mirror Lippard’s attack on Philadelphia’s moral shortcomings, but they often miss the labor activist’s more fundamental critique of high capitalism.

The Turmoil of Slavery

While this new aristocracy of money exposed by Lippard and his followers represented one of the major contradictions in American society, slavery was certainly another. Brown informed the readers of Wieland that dark secrets lay in the exploitation of forced African labor, but both Bird and Lippard addressed Philadelphia’s problematic relationship with slavery much more directly. One of Sheppard Lee’s many narratives, for instance, takes readers into the slaveholding South, where a Philadelphia Quaker is to be lynched for alleged abolitionist activities—with the added irony that the Quaker is at best on the fence about the issue and has turned over fugitive slaves to the authorities just moments before. Lippard’s work includes frequent references to slaves “acquired” below the Mason–Dixon line who remain in bondage in Philadelphia, even though the institution had been outlawed there since 1780. In characters like the Creole slave boy “Dim” (The Quaker City), Lippard captures in gothic ornament the political climate of the years between Prigg v. Pennsylvania (an 1842 Supreme Court decision undermining local laws freeing slaves brought into the state) and the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Philadelphia’s double-faced position on the issue culminated in an 1849 race riot, which Lippard fictionalized in characteristically stark images in his novella The Bank Director’s Son (1851). Although both Bird and Lippard were by no means free from racial prejudice—indeed their depictions of slaves often rehearse overtly racist stereotypes—they nonetheless brought the issue to the center of their works, reminding Philadelphia, as one of the major hubs of trade for the South, of its duplicitous role in perpetuating human bondage.

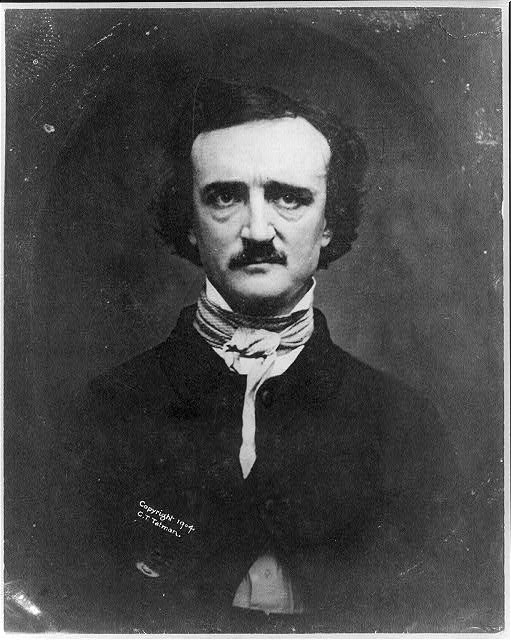

While Bird’s and Lippard’s satirical interventions into Philadelphian society were hugely successful, Edgar Allan Poe spent some of his most productive years (1838 to 1844) in the city and stands as its most influential gothic author. From “The Tell-Tale Heart” (1843) and “The Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1841) to his only completed novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket (1838), some of Poe’s most famous pieces were produced in Philadelphia. Even his renowned poem “The Raven” was originally written for a local literary journal, though it was declined and later published in a New York monthly. Well-acquainted with the local gothic tradition, Poe’s fictions show an indebtedness to Brown’s work, he positively reviewed Bird’s Sheppard Lee, and he became a personal friend of Lippard, who lent Poe financial support for his writing.

Nonetheless, Poe’s gothic differs markedly from his contemporaries. Modeling his writing on English and German high culture and reshaping it for a popular American taste, many of Poe’s tales (with the exception of his Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym) take place either in undisclosed locations or shadowy European mansions. Although certain events in Philadelphia’s history have been traced to Poe’s writings (such as a local insanity-defense trial that also inspired Lippard), none of his tales are specified as taking place in the city, and only one, the satiric “How to Write a Blackwood Article” (1838), even mentions Philadelphia. Instead of directly exposing local, social wrongs through gothic satire (as his benefactor Lippard had done) Poe’s fictions take a more psychological turn, brooding on issues of the mind, murderous urges, hallucinations, and the supernatural. Still, in Poe’s proto-modern gothic, we can sense the City of Brotherly Love lurking behind many seemingly European plots. In tales like “The Man of the Crowd” (1840), we might also hear the buzz of Philadelphia’s busy downtown streets, while pieces like “The Masque of the Red Death” (1842) seem to echo Philadelphia’s past—in this case, the yellow fever epidemic of 1793 that also inspired Brown’s Arthur Mervyn (1799).

While the era of the American gothic appeared to come to a slow close with the deaths of Poe (1849) and Lippard (1854) and the rise of literary realism, some of its central themes had a remarkably resilient afterlife. Besides the continuing presence of Poe, the criminal underbelly of Lippard’s Philadelphia reappears in 1950s noir fiction. And while the Old Philadelphia Mystery Series (1998-2000), by Mark Graham (b. 1950), revisits a gritty, murderous Philadelphia of the past, one can also hear faint echoes of the violent rioters of The Bank Director’s Son or the drug-fueled robbers of Mysteries and Miseries of Philadelphia in works set in modern-day Philadelphia such as Steve Lopez’s (b. 1953) Third and Indiana (1994) or Solomon Jones’s (b. 1967) Pipe Dream (2001). As deep as the mysterious caverns below the City of Brotherly Love may be, it appears that its lurid secrets never quite seem to stay down.

Stefan Schöberlein is a doctoral candidate at the English Department of the University of Iowa and the managing editor of the Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University