Literary Societies

Essay

Philadelphia’s literary societies typically have combined the social with the intellectual and artistic, with ongoing shifts in the balance between the two. As descendants succeeded the founding members, they prized the relationships and traditions handed down over generations, perhaps more than the original literary pretext of the organization.

Philadelphia has often been described as a “clubby city,” which means that it has had a long tradition of voluntary associations. Literature has played a substantial role in the formation of those organizations since the early eighteenth century. Philadelphia, perhaps more than any other major American city, long nurtured a pragmatic, Enlightenment culture that emphasized science, medicine, engineering, and exploration that sustained a tension between writing as a form of art and writing as a means of communication.

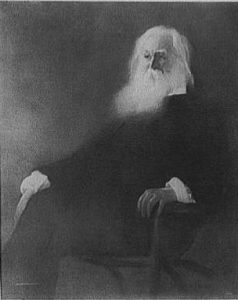

The Quakers of Philadelphia, like the Puritans of Boston, favored a plain style of writing. Benjamin Franklin (1706-90)—a product of both cities—heeded his father’s warning that poets are generally beggars. Edgar Allan Poe (1809-49), for example, struggled to earn a subsistence before the emergence of local and national publishing industry in the decades before the Civil War. Through much of the nineteenth century, groups that supported literature were primarily for social elites, and they typically encouraged admiration and imitation of European literary writers, particularly English ones, thus impeding the development of new literary forms and subject matter. In that context, poets such as Walt Whitman (1819-92) struggled against an entrenched “Genteel Tradition,” but they gradually found support among more progressive literary societies created at the end of the nineteenth century that included women and more individuals from outside the circles of Philadelphia gentlemen. The interaction between those different visions of literature and the composition of the groups that supported them, characterized the city’s literary culture well into the twentieth century.

Some members of Philadelphia’s founding generations considered themselves citizens of the international “Republic of Letters.” James Logan (1674-1751), secretary for William Penn (1644-1718), was a polymath whose books eventually made up the core collection of the Library Company of Philadelphia. Logan sought out gifted young men, like the naturalist John Bartram (1699-1777), and gave them access to his collection and sometimes introduced them to his European correspondents. One of those protégés was Benjamin Franklin, then a young printer, who in 1727 created the “Junto.” A free-thinking, mutual-aid society, the Junto met on Friday evenings to discuss politics, philosophy, science, and strategies for professional advancement. Each member had to produce an essay every three months to be critiqued by the other members. Some members had literary interests; many were bibliophiles. The Junto created the first subscription library in the colonies in 1731; it eventually became the Library Company of Philadelphia. They also helped to found the American Philosophical Society in 1743 and the College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania) in 1749. The Junto lasted for about forty years and inspired other groups like it, making Philadelphia’s ordinary citizens more literate and bookish, if not always more literary.

Expansion of Literary Writing

Until the early national period, literary writing, in general, remained the province of the highly educated, Anglophile, and typically loyalist elites. The first provost of the College of Philadelphia, William Smith (1727-1803), became the mentor for a coterie of writers and artists that included Thomas Godfrey Jr. (1736-63), Nathaniel Evans (1741-67), Francis Hopkinson (1737-91), Joseph Shippen (1732-1810), James Sterling (1701-63), and Benjamin West (1738-1820). In 1757, William Bradford (1719-91), with Smith as editor, published the American Magazine, or Monthly Chronicle for the British Colonies. Smith’s “society of gentlemen” contributed a substantial amount of poetry, as well as political and religious essays, and attempted to represent the colonies favorably to the parent country. Also in this era, Elizabeth Graeme Fergusson (1737-1801) presided over the first literary salon in the American colonies. Graeme’s “Attic Evenings” included women and men, at her family estate, Graeme Park in Horsham, beginning around 1767. Graeme had been engaged to Franklin’s son William (c. 1730-1813) and had met the Irish novelist Laurence Sterne (1713-68) as well as King George III (1738-1820). Fluent in several languages, Graeme kept travel journals and wrote poetry, translations, and satire, typically using the pseudonym “Laura.” Her gathering included writers, musicians, and political figures drawn from Philadelphia’s elite society, including Evans, Hopkinson, Rush, and West. Graeme’s salon faded with onset of the American Revolution and the confiscation of loyalist property afterward.

The first decades of the nineteenth century witnessed significant growth in the number of social groups with literary interests, and participation became more democratized as literary writing began to become an occupation as well as an avocation. Joseph Dennie (1768-1812) convened the Tuesday Club, composed of genteel amateurs dedicated to the appreciation of “polite and elegant literature,” but it also included a few of the nation’s first professional literary writers. Dennie founded the Port Folio magazine in 1801, editing it as “Oliver Oldschool” until his death in 1812. Drawing upon this group for poems, essays, satires, and translations, the Port Folio during those years was Anglophile, Federalist, and anti-populist. In later years, Walsh hosted his own high-minded soirées involving the upper crust of Philadelphia society, including Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844), president of the Second Bank of the United States; Bishops William White (1748-1836) and John Cheverus (1768-1836); and Nathaniel Chapman (1780-1853), the founding president of the American Medical Association. Conservative in politics and taste, though more Francophile than Anglophile, and Catholic, Walsh edited The American Quarterly Review, favoring regional authors drawn from his extensive social connections but also including national figures such as James Fenimore Cooper (1789-1851) and George Bancroft (1800-91). Walsh left Philadelphia in 1835 when he was appointed consul general in Paris, where he assembled a new group of American expatriates and travelers. In the 1840s, George Rex Graham (1813-94), editor of Graham’s American Monthly Magazine of Literature and Art also gathered writers around him, but he cultivated aesthetic tastes such as romanticism that were at odds with those of Dennie and Walsh.

Significantly different in the composition of its guests, and in the topics of their conversations, were the Saturday-night gatherings sponsored by Caspar Wistar (1761-1818) at his house at Fourth and Prune (now Locust) beginning around 1811. Wistar was then a famous professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania and the fourth president, after Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), of the American Philosophical Society. Originally, the group mainly consisted of his academic colleagues, but it eventually broadened to include a wider swath of Philadelphia society, including some members of the coteries of Dennie and Walsh. The latter’s partial deafness, some joked, was feigned to excuse him from conversation in such challenging company. Initially, their interests were inclined towards the sciences, but they gradually expanded to include a wider range of interests, including literature. After Wistar’s death, a group of friends continued the “Wistar Parties,” somewhat irregularly, until the Civil War when many social clubs were suspended; it was revived in 1867 as the Saturday Club. A prominent economist, the younger Carey assumed a leadership role in the intellectual life of the city, hosting what came to be called the “Carey Vespers” at his mansion at 1102 Walnut Street. His interests included music, theater, and literature, as well as vigorous round-table discussions of politics with some of the powerful figures of the Civil War era, including Archbishop William Henry Elder (1819-1904) and General (later U.S. president) Ulysses S. Grant (1822-85).

Literature as Academic Subject

By the middle of the nineteenth century, literature began to emerge as a field of academic study. Philadelphia’s Shakspere [sic] Society, perhaps the oldest continuously meeting group of its kind, was founded in 1851 during a period in which “The Bard” became a touchstone of high-cultural legitimacy in the United States. The founders, like those of nearly all such societies, were socially elite members of the professional classes. They are said to have been inspired by the dramatic readings of actress Fanny Kemble. Horace Howard Furness (1833-1912) was the founding member. He was a lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania, editor of a variorum edition of Shakespeare’s works, and son of Unitarian minister William Henry Furness and brother of the architect Frank Furness (1839-1912). H.H. Furness Jr. (1865-1930), also a Shakespearean, continued his father’s service. The society entertained visiting scholars and papers were delivered and critiqued by the members. Exclusively male, they met at the houses of members and, for a period, at the socially elite Philadelphia Club at Thirteenth and Locust. For more than 150 years, the society preserved a tradition of fellowship and, increasingly, literary appreciation as academic literary scholarship has become more specialized and less accessible to nonprofessionals.

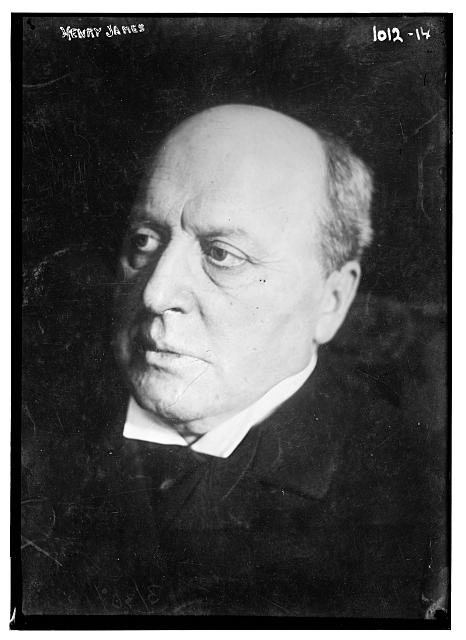

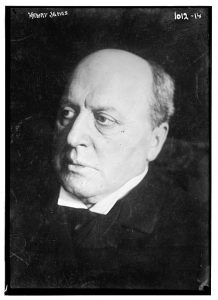

Following a similar course, the Social Art Club, begun in 1875, became primarily a Gilded Age gentleman’s society, attracting University of Pennsylvania faculty members, along with surgeons and railroad executives, when it was renamed The Rittenhouse in 1888. The novelist Henry James (1843-1916) described The Rittenhouse in The American Scene (1907) in the context of Philadelphia society’s “consanguinity,” its complex familial interconnections that were reflected, as much as by interests, in the city’s club memberships. Business talk was prohibited among the leather chairs, books, and paintings of the Beaux-Arts mansion at 1811 Walnut Street; their interests remained more literary, artistic, and antiquarian than the Philadelphia Club or the Union League on South Broad Street. In addition to James, their guests included literary luminaries such as William Dean Howells (1837-1920) and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-82). Membership declined in the twentieth century. The Rittenhouse became less exclusive, the clubhouse was sold in the 1990s (the façade remains), and members then shared a building at 1519 Locust Street, with the Acorn Club, founded in 1889, one of the oldest surviving women’s clubs in the United States with an interest in literature, music, and the arts. Similar in many ways, and likewise founded in 1875, was the exclusive Penn Club, based at 720 Locust Street. The purpose of the organization has been to bring authors, artists, politicians, and scientists of distinction into association with their members. It has hosted receptions for speakers, such as Dion Boucicault (c.1820-90), Ulysses Grant, William Pepper, Carl Schurz (1829-1906), and Bayard Taylor (1825-78).

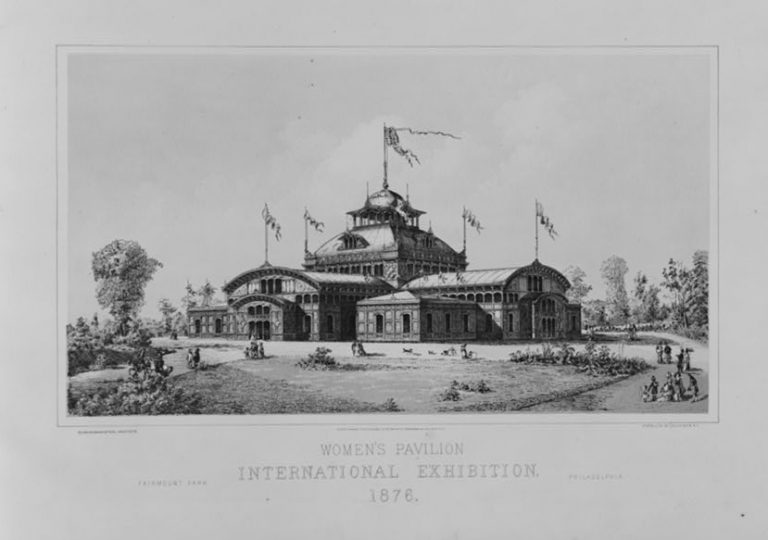

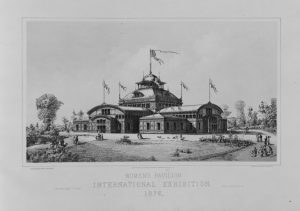

The decades after the Civil War saw a flowering of women’s literary societies that maintained a more politically progressive agenda and a venue for literary writers who were excluded from the conservative men’s clubs. The New Century Club, founded in 1877, grew out of the activities of Women’s Pavilion at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia. Sarah Catherine Fraley Hallowell (1833-1914), a journalist for the Philadelphia Public Ledger, was the founder and first president. The club’s interests were eclectic, including science, literature, and art, as well as municipal reform and women’s suffrage. Initially based at 1520 Chestnut Street, the club grew to more than four hundred members by the time it occupied an Italian Renaissance building at 124 S. Twelfth Street, designed by Minerva Parker Nichols (1860-1949); it was demolished in the 1970s. Members took a special interest in the conditions of working women, forming a second organization called New Century Guild in 1882 with a separate building standing at 1307 Locust Street. Around 1887, the New Century Club also sponsored a Browning Society, one of many in the United States, dedicated to the study and discussion of the work of Robert (1812-89) and Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-61). The organization helped to establish the status of women as literary authors worthy of study like Shakespeare.

Expansion of Clubs

The New Century Club was politically moderate compared to the Contemporary Club founded about a decade later in 1886 partly by its own members such Emily Sartain and Florence Earle Coates (1850-1927). The University of Pennsylvania archaeologist Daniel Garrison Brinton (1837-99) served as the club’s first president. Other founders included the ophthalmologist and literary biographer George M. Gould (1848-1922) and the socialist writer Horace Traubel (1858-1919), who became the leading disciple of Walt Whitman (1819-92). The author of Leaves of Grass (1855-92) was one of the first writers invited to speak at the club in 1886. One member recalled liking Whitman, despite his plain clothes—and reputation as “the immoral author of an indecent book”—better than Henry James, who was a disappointment, apart from the introduction provided by Agnes Repplier (1858-1950), who served as the Contemporary Club’s first female president and later became the doyenne of Philadelphia’s literary society. For decades, the club hosted monthly lectures. In its time, from the 1880s to 1920s, the Contemporary Club was the leading venue for progressive literary and political conversation, but it, too, declined, as the founding members died, until it ceased meeting in 1950s.

In the wake of Whitman’s visit, members of the Contemporary Club, particularly Traubel and Brinton, sought to raise funds to support the poet who had been living in nearby Camden, New Jersey, since 1873, after suffering a stroke. Their comrades included the psychiatrist Richard Maurice Bucke (1837-1902) and lawyer Thomas Harned (1851-1921). On May 31, 1889, the group rented a hall in Camden to celebrate Whitman’s seventieth birthday, and the testimonials of the evening were published in the same year as Camden’s Compliment to Walt Whitman. After the poet’s death in 1892, they gathered in Philadelphia on his birthday and named themselves the “Walt Whitman Reunion Association.” A jeweler, John H. Johnston (1837-1919), served as chairman. The group met again in New York in 1893, and then in Philadelphia in 1894, renaming themselves the “Walt Whitman Fellowship: International” with Brinton as president. Other members included the naturalist John Burroughs (1837-1921), “The Great Agnostic” Robert Ingersoll (1833-99), and Philadelphia publisher David McKay (1860-1918). From 1895 to 1900, the fellowship alternated meetings between Boston and Philadelphia, then, from 1901 to 1919, resumed alternating with New York. The fellowship eventually had more than two hundred members; many were even more self-consciously radical and bohemian than those of the Contemporary Club. By the time of Traubel’s death in 1919, when the group ceased meeting, they had published 123 “Walt Whitman Fellowship Papers” and became the parent organization for several other Whitman-related literary societies.

If Philadelphia club society was fading by the end of the Gilded Age, there were still a few more notable organizations that emerged in its twilight. The Writeabout Club, founded in 1897, lingered until the 1950s, hosted weekly gatherings to present short stories and poems. However, Philadelphia’s most well documented literary society from that time is the Franklin Inn. Inspired by Boston’s Tavern Club, it was founded in 1902 by members of the University Club, who formerly met at 1316 Walnut Street. S. Weir Mitchell served as the Franklin Inn’s first president. Members once had to be the author of a book that was not about medicine or law, and many Philadelphia-based authors have been members up to the early twenty-first century. A formal dinner is held each year on Benjamin Franklin’s birthday, as well as regular luncheons and evening events, at the building the Franklin Inn has occupied since 1907: 205 S. Camac Street. The inn also has played host to the Philobiblon Club, founded in 1893, for bibliophiles, book collectors, and dealers.

Most of the literary societies that flourished in the nineteenth century gradually declined in the next century as new forms of entertainment came to occupy Americans’ leisure time, and as Philadelphia’s social elite became less regionally-identified. Nevertheless, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, in addition to the activities of survivors such as the Franklin Inn, frequent literary events could be found: speakers and symposia at libraries, colleges, and universities, as well as poetry slams at neighborhood bars. Even in the absence of so many literary societies, the increasing scale and diversity of Philadelphia suggested that social activity involving literature was more extensive in the twenty-first century than at any time in its history, and that that activity was more inclusive of the residents of the region. In the era of the Internet, the formation of common-interest groups became more rapid, more specialized, and more globally dispersed than ever before. But, at the same time, the desire of people to come together to express their experiences in literary ways, however that is defined, remained a characteristic feature of life in Philadelphia, not just in formally established clubs, but in any place where people gather socially.

Notable Literary Club Members

The Junto: John Bartram (1699-1777), Joseph Breintnall (died 1746), William Coleman (1704-69), Thomas Godfrey (1704-49), Hugh Meredith (1697-1749), William Parsons (1701-57), Nicholas Scull (1687-1761), and Philip Syng (1703-89), among many others.

The Tuesday Club: Nicholas Biddle (1786-1844), Horace Binney (1780-1875), Charles Brockden Brown (1771-1810), Thomas Cadwalader (1779-1841), John Ward Fenno (1778-1802), Joseph Hopkinson (1770-1842), Charles Jared Ingersoll (1782-1862), John Blair Linn (1777-1805), Richard Rush (1780-1859), and Robert Walsh (1784-1859).

Wistar Parties: The antebellum gathering included the Bache descendants of Benjamin Franklin, William Henry Furness (1802-96), Isaac Israel Hayes (1832-81), Isaac Lea (1792-1886), Thomas Nuttall (1786-1859), Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), Thomas Say (1787-1834), and William Tilghman (1756-1827), as well as the publisher Mathew Carey (1760-1839) and his son Henry (1793-1879).

Walsh’s Circle: Willis Gaylord Clark (1808-41), Reynall Coates (1802-86), Thomas Dunn English (1819-1902), Fanny Kemble (1809-93), Morton McMichael (1807-79), Charles Jacobs Peterson (1818-87), Edgar Allan Poe (1809-49), and Richard Penn Smith (1799-1854).

The Rittenhouse: Members included George Boker (1823-90), Thomas DeWitt Cuyler (1854-1922), the Furness brothers, Henry Charles Lea (1825-1909), S. Weir Mitchell (1829-1914), William Pepper (1843-98), J. William White (1850-1916), and Owen Wister (1860-1938).

The Penn Club: Early members included the president of the Philadelphia Stock Exchange, Wharton Barker (1846-1921), George Boker (1823-90), George W. Childs (1829-94), Anthony Drexel (1826-93), and H. H. Furness (1833-1912).

The New Century Club: Early members included leading women in the arts such as Elizabeth Croasdale (1858-1935) and Emily Sartain (1841-1927), head of the School of Design for Women, as well as abolitionist Eliza Sproat Turner (1826-1903) and physician Clara Marshall (1847-1931).

The Contemporary Club: Notable speakers included H. H. Furness, Hamlin Garland (1860-1940), Brander Matthews (1852-1929), S. Weir Mitchell, Maxfield Parrish (1870-1966), Robert E. Peary (1856-1920), Joseph Pennell (1857-1926), Samuel Pennypacker (1843-1916), Margaret Sanger (1879-1966), Wu Tingfang (1842-1922), Carl Van Doren (1885-1950), Booker T. Washington (1856-1915), Talcott Williams (1849-1928), and Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924), when he was a professor at Princeton.

Walt Whitman Fellowship: Members included writers such as Max Eastman (1883-1969) and John Erskine (1879-1951) and artists such as Marsden Hartley (1877-1943) and Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946).

The Writeabout Club: Members included Francis Churchill Williams (1869-1945), Edward Robins (1862-1943), Edward W. Mumford (1868-1941), Rupert S. Holland (1878-1952), E. Lawrence Dudley (1879-1947).

The Franklin Inn: Exclusively male until 1983, the “Innmates” included Edward Bok (1863-1930), Charles Heber Clark (1841-1915), H. H. Furness, Henry Charles Lea (1825-1909), John Luther Long (1861-1927), R. Tait McKenzie (1867-1938), John Bach McMaster (1852-1932), Langdon Mitchell (1862-1935), Ellis Paxon Oberholtzer (1868-1936), Arthur Hobson Quinn (1875-1960), J. William White (1850-1916), and Owen Wister (1860-1938).

The Philobiblon Club: William Pepper (1843-98) was the first president, followed by Pennypacker. Others members included A.S.W. Rosenbach (1876-1952), the literary historian Robert Spiller (1896-1988), and Edwin Wolf II (1911-91), librarian of the Library Company of Philadelphia founded by Franklin.

William Pannapacker, who holds a Ph.D. in American Civilization from Harvard University, is the DuMez Professor of English at Hope College. He is the author of Revised Lives: Walt Whitman and Nineteenth-Century Authorship (2004) and numerous articles and reviews on American literature and culture. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University