Lower Delaware Colonies (1609-1704)

Essay

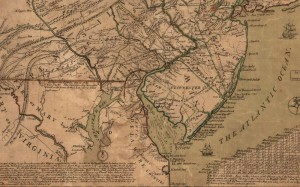

The colonies that became the state of Delaware lay in the middle of the North American Atlantic coast, extending about 120 miles north from the Atlantic Ocean along the southwestern shore of the Delaware (South) Bay and River to within 10 miles of Philadelphia. Between 1609 and 1704, the area was a contested borderland between north and south, as a dozen native and colonial political and commercial regimes sought to assert authority over the region. William Penn (1644-1718) ultimately gained control of the area as an addition to his land grant for Pennsylvania.

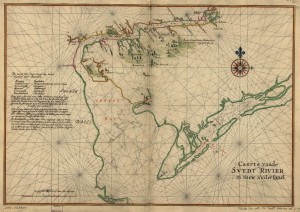

The bay and river—named in 1610 by English explorer Samuel Argall (1580-1626) in honor of Virginia’s governor, Thomas West, Lord De La Warr (1576-1618)—provided a rich, diverse estuarine environment for natives and colonists. A network of natural harbors and navigable rivers enabled trade along the coast and access into the interior. Early historic maps show extensive oyster-laden shoals in the shallow southern reaches of the bay. Shad, sturgeon, and other fish migrated annually up the river. An extensive marsh system lined the bay and river, broken by broad meadows and savannahs. Waterfowl, small mammals, fish, and salt hay abounded, and these lands proved amenable to grazing cattle. The forested coastal plain provided wild game and timber for structures, fencing, and shipbuilding, as did the Cypress Swamp in southern Sussex County. The northern Piedmont hills yielded flint for native people’s stone toolmaking and Europeans exploited the iron ore at Iron Hill, near Newark, New Castle County.

Lenape and Susquehannocks

For most of the seventeenth century, Lenape Algonquian people exerted the greatest political and economic control over the country from central New Jersey through eastern Pennsylvania and along the Delaware Bay to its mouth at Cape Henlopen (Sussex County). Led by sachems and councils of elders, they lived in unpalisaded towns and spoke Unami. Over the course of the century, these Lenape natives created with European settlers a distinctive society that valued peace over conflict, religious freedom, collaboration, respect for diverse people, and local authority. Nonetheless, desire for profits led to contention, and native traders shifted among European nations to obtain the quantity and quality of goods they sought. Exchange provided the source of the Lenapes’ power, which they used to provoke colonial rivalries.

Inland, Susquehannock (Minquas) peoples living in fortified villages along the Susquehanna River proved especially determined to maintain independence in the fur trade, and played Swedes, Dutch, and English against each other. A decade of intermittent war with Lenapes between 1626 and 1636 typified the larger contest for control over furs in the North Atlantic world. The outcome earned Susquehannock traders the right to do business in Lenape areas along Delaware Bay and instigated a trade alliance among the groups.

Dutch Republic and Sweden along the Delaware

While the Lenapes defended their homeland against the Susquehannocks and northern Iroquois, Europeans from the Dutch Republic’s West India Company, the City of Amsterdam, and Sweden established small trading colonies. Lenapes welcomed trade with Dutch sailors, who entered the bay and river by about 1615. The Dutch West India Company established Fort Nassau on the eastern side of the Delaware River in 1626 as part of its colony of New Netherland, an outpost of the Dutch commercial empire and potential source of furs for the expanding European market. Dutch activity expanded in 1629, when officials bargained with a southernmost Lenape community, Sickoneysincks, for a tract of land reaching from Cape Henlopen to the mouth of the Delaware River. By 1631 the resulting colony, Zwaanendael, consisted of about thirty colonists housed in a palisaded fort. Within a year, however, the venture ended in violence. After the Sickoneysincks determined that the Dutch intended to build an agricultural settlement, not merely a trading fort, they destroyed the fort and its occupants. Though the colony failed, its brief existence prevented the future area of Delaware, or at least southern Delaware, from being adjudged part of Maryland.

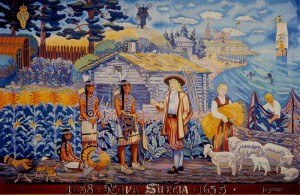

In the mid-1630s, Peter Minuit (c. 1580-1638), former director of New Netherland, negotiated with the Swedish government to establish the New Sweden colony under Swedish protection. He understood the strategic geographical importance of the lower Delaware Valley, and that the Dutch West India Company had insufficient resources to devote to its development and defense. The New Sweden Company, under leadership of Minuit and other investors, benefited from Dutch colonial experience and funding while enjoying the added advantage of patronage and the protection of the Swedish monarch. For the crown, New Sweden promised to strengthen the nation’s new position as a European power, naval experience, and imperial growth.

The New Sweden Company built Fort Christina, the first permanent European settlement in Delaware, in 1638. The fort, which became the base of one of two primary European settlements along the west side of the river in the seventeenth century, stood at the confluence of the Brandywine and Christina Creeks, later Wilmington, northern New Castle County. At its peak, the colony claimed territory along both sides of the Delaware from the mouth of the bay to the falls (later Trenton, New Jersey), and the settlers traded with Lenapes and Susquehannocks. New Sweden officials established fortifications along the river in an effort to control trade with Indian fur suppliers. Most New Sweden settlers lived along the tributaries of the Delaware River between what later became Wilmington and Philadelphia.

Despite their nations’ alliance in Europe, Dutch West India Company and New Sweden Company settlers believed the lower Delaware Valley could not accommodate them both. They maneuvered for trade advantages, particularly after Peter Stuyvesant (d. 1672) became director-general of New Netherland in 1647. By 1650, the Dutch administration on Manhattan Island and directors in Amsterdam had realized the importance of settling the lower Delaware. Stuyvesant provocatively replaced Fort Nassau in 1651 with Fort Casimir, a second principal European settlement just south of the Swedish Fort Christina. Stuyvesant was concerned not only with Swedes but with English efforts to colonize the river.

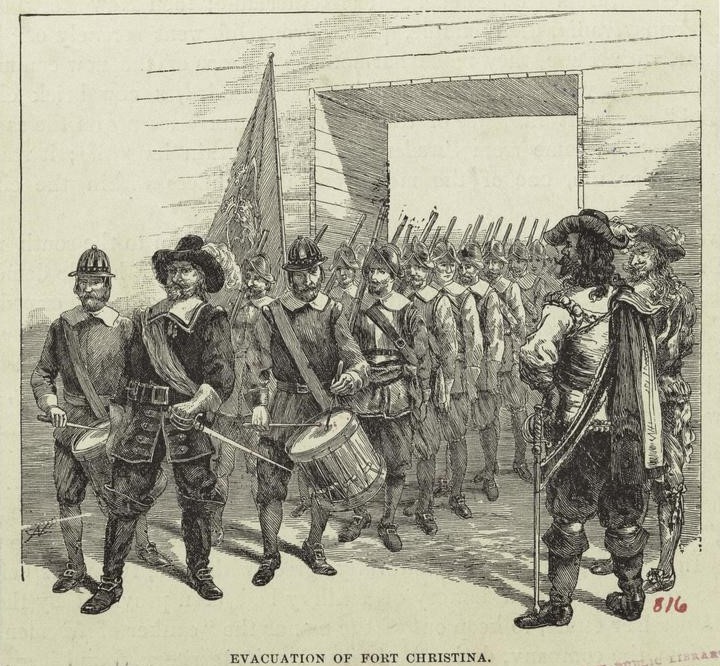

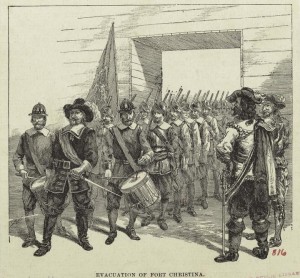

After Stuyvesant invaded New Sweden in 1655, Sweden lost its tenuous foothold in this middling borderland. The Dutch then divided the settlements on the Delaware into two colonies. The City of Amsterdam created its “City Colony” in the region surrounding Fort Casimir below the Christina River, centered on New Amstel (later New Castle). Two rows of house and garden plots extended south from the fort along the river. Purportedly 110 houses were completed within a year for Dutch administrators, soldiers, traders, and a mix of settlers from across northern Europe. Within a few years, however, political infighting and economic turmoil led to outmigration, and the population plummeted. Settlers arriving from Maryland and Virginia caused concern because Charles Calvert, Lord Baltimore (1637-1715) considered the lands between the Chesapeake Bay and Delaware River part of his proprietorship. Plans to profit from the tobacco trade with Maryland were stymied by epidemic and the inability of farmers to support the population.

The second Dutch colony, the “Company Colony” north of the Christina River, remained under the administration of Dutch West India Company with a predominantly Swedish and Finnish population. Dutch administrators remained suspicious and distrustful of these Finnish and Swedish settlers. The Dutch renamed the Swedes’ Fort Christina as Fort Altena, but the “Swedish nation” remained strong in other settlements upriver. The Dutch depended on the Swedes’ skills as farmers, interpreters, messengers, diplomats, and soldiers.

English: Duke of York

The unstable, contested relationships among the multinational, multicultural population of the lower Delaware Valley paved the way for conquest by the English in 1664, after Charles II (1630-85) granted his brother James, Duke of York (1633-1701), proprietary rights to land extending from New England to the east side of Delaware Bay. A bloodless invasion of the west shore at Fort Casimir extended the English claim, and the Duke created New Castle County (1664). Beginning in the late 1660s, Swedes, Finns, and Dutch from the Christina Valley and New Castle moved west and south, while English settlers, including some from Maryland, moved to the west bank of the Delaware in small but increasing numbers. Often they brought enslaved Africans with them. In 1670 Governor Francis Lovelace (c. 1621-75) established the first local court in southern Delaware, at Whorekill (later Sussex County). By the mid-1670s, distinct communities of Finns, a wealthy elite, and multiethnic peasants had emerged along the west coast of the lower Delaware. The “Swedish nation” remained autonomous and resilient through alliances with Lenapes and Susquehannocks.

Under the Duke of York, the tobacco economy in Delaware flourished. By 1680, pork and corn joined tobacco as the principal agricultural exports to England, Scotland, and the West Indies. Sufficient population growth and economic development had occurred along the central Delaware coast to warrant the division of Kent County from Whorekill in that year. In some areas these new colonists and descendants of earlier settlers expanded into grain farming and milling and established commercial orchards and animal husbandry operations.

English: William Penn

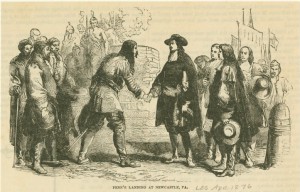

In 1681 William Penn convinced the English Crown to grant him a charter to 45,000 square miles on the western side of the Delaware River, with a southern boundary on the river twelve miles north of New Castle. Two years later, just before Penn sailed for Pennsylvania, the Duke of York deeded him possession of the three Delaware counties of New Castle, Kent, and Sussex (the Lower Counties). At the time, only about four hundred nonnative inhabitants—Swedish, Finnish, Dutch, and English settlers, and approximately one hundred enslaved Africans—shared with Lenape peoples the entire settled area from Cape Henlopen to New Castle.

In the 1690s, many Lenapes sold claims along the Delaware and moved west into former lands of Minquas-Susquehannock peoples. The borderland region remained torn by religious schism and political rivalry. An extended dispute with Lord Baltimore over the Maryland-Three Lower Counties of Delaware boundary also plagued Penn’s administration.

Penn sought to establish a predominantly Quaker colony. The ethnically, religiously diverse Lower Counties resisted efforts to incorporate them under one proprietary government for Pennsylvania based in Philadelphia. Conflicts arose over autonomy, representation, divergent economic interests, and military defense. Although the region remained Penn’s domain, beginning in 1704 a separate Assembly governed the Lower Counties of Delaware.

By the early eighteenth century, the increasingly European-American landscape of Delaware’s three counties consisted of a few small port towns like New Castle in New Castle County and Lewes in Sussex County and dispersed farmsteads where the land possessed good agricultural qualities. Farmers located their farmsteads near waterways or roads, and cleared small areas for buildings and tobacco, rye, barley, and wheat fields, orchards, and livestock grazing lands. As Philadelphia rapidly grew to be the second-largest city in English North America, Delaware became part of the city’s agricultural and commercial hinterland.

Lu Ann De Cunzo holds a Ph.D. in American Civilization with a specialization in historical archaeology. Her research has addressed diverse themes and topics of lower Delaware Valley history and cultures between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries. She is Professor and Chair of Anthropology at the University of Delaware. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History