Moravians

Essay

In the eighteenth century, the Moravian church grew from a small group of Protestant dissenters in Germany to a global church with its most important American center at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, about fifty miles northwest of Philadelphia. The Moravians were best known for their experiments in communal living and their global missions, including a number of missions to Native Americans. In 1762, they significantly altered the character of their communal experiment at Bethlehem and in later years modified or abandoned some of their most distinctive characteristics. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, they continued their global mission, even as the church in the United States (by then a mainline Protestant denomination) remained small.

The Moravians’ origins go back to 1722, when a German nobleman, Count Nicolaus von Zinzendorf (1700-60), allowed a small group of Protestant dissenters from Bohemia and Moravia to settle on his land in Saxony. These dissenters, called the Unitas Fratrum, drew inspiration from the Czech reformer Jan Hus (1369-1415) and other Protestants and had faced persecution from Catholic authorities. Zinzendorf became the most influential and powerful Moravian leader of the eighteenth century. Ordained as a Lutheran minister in 1735 and consecrated as a Moravian bishop in 1737, Zinzendorf and his followers believed that God wanted them to send missionaries around the world. As part of that effort, in 1741 Zinzendorf traveled to Pennsylvania, where the Moravians founded Bethlehem. The town grew rapidly from only 131 settlers in 1741 to more than 1,200 Moravians in Bethlehem and the surrounding region by 1753. Other distinctively Moravian communities followed, including Nazareth, Gnadenthal, and Christiansbrunn in Pennsylvania and Wachovia in North Carolina. Other Moravians settled in largely non-Moravian areas, including Philadelphia, New Jersey, New York, and elsewhere.

In the eighteenth century, Bethlehem served two purposes–it was designed both as a model community whose members were devoted to God and as the home base and economic support for local and global missionary efforts. The Moravians purchased thousands of acres of land and became successful farmers. They also engaged in skilled trades, including blacksmithing, carpentry, and pottery making. During the first twenty years of the settlement (1741-62), Moravian workers at Bethlehem drew no wages. The church provided their food, clothing, and housing, and they saw themselves as working for the glory of God and the support of the Moravian missionary effort.

Separation of the Sexes

During these years, the residents of Bethlehem lived in same-sex communal housing and worked in communally owned enterprises. Church members lived, prayed, and worked in a number of cohorts, or “choirs,” with others of the same sex and similar age. Moravian leaders believed that this system, which kept men and women separated at nearly all times, reduced the likelihood of sexual sin and encouraged both men and women to focus their attention on God.

Although newcomers to America in the 1740s, Moravians shared in the emotional fervor of the First Great Awakening, a series of Protestant revivals that spanned the colonies. Like other evangelicals, the Moravians emphasized conversion, moral living, and a personal and heartfelt relationship with Christ. Moravians corresponded with the Methodist leaders John Wesley (1703-91) and Charles Wesley (1707-88) and even purchased land from the itinerant evangelist George Whitefield (1714-70), although Whitefield eventually rejected the Moravians because they did not believe in predestination, the belief that God had already chosen who would be saved and who would be damned.

Although the Moravians shared many beliefs with other evangelicals, they also had distinctive ideas and customs that set them apart. Zinzendorf encouraged a simple, childlike faith and trust in God and a mystical devotion to Jesus, focusing particularly on Jesus’s love and self-sacrifice for humanity. Moravian prayers and hymns invited worshippers to contemplate the wounds of Christ and to regard themselves (men and women alike) as the brides of Christ. Moravians considered the wound in Jesus’s side particularly significant, viewing it as a mystical opening where believers could shelter and as a gate to heaven. Another distinctive characteristic was the practice of submitting important questions to “the Lot.” Moravians believed that God directed all earthly affairs, and there was therefore no such thing as chance or luck. Before making important decisions (such as those regarding marriages, church membership, and the choosing of ministers), the Moravians drew lots. In setting up the draw, one slip of paper gave an affirmative answer, a second one a negative answer, and a third one was left blank. If the blank one was drawn, no action would be taken at the time, but the question could be resubmitted at a later date.

Zinzendorf and his fellow Moravians believed that men and women of all nations and peoples could be saved. As a result, in the eighteenth century they sent missionaries to many places, including Africa, the Caribbean, the British Isles, Scandinavia, and across the British colonies in America. In America, they hoped both to encourage unity among Protestant Christians, and to convert African slaves and Native Americans.

Unity Proves Elusive

The quest for unity among Protestants proved elusive. Believing that true Christians could be found in all churches, Zinzendorf hoped to dissolve denominational boundaries. His vision soon led to conflict between the Moravians and other German Christians in Pennsylvania. In 1742, Zinzendorf (an ordained Lutheran clergyman) was invited to preach to the Lutheran congregation in Philadelphia. His preaching was so powerful that the Lutherans asked him to become their pastor. He accepted, although his leadership would divide the congregation. To avoid further dissension, Zinzendorf and his followers left the congregation and Zinzendorf founded a new church near Bread and Race Streets, shared by Lutherans and Moravians. Zinzendorf also arranged a series of meetings or synods between Moravians and other German Christians. Seven synods took place between January and June 1742 in Philadelphia, Germantown, and elsewhere in Pennsylvania. Although more than a hundred representatives of various denominations attended the first synod in Germantown, the delegates found Zinzendorf overbearing and feared that he wanted to absorb the other churches into the Moravians. As a result, the later synods were poorly attended. Zinzendorf’s dream of uniting German Christians in America had failed.

The Moravians hoped for converts across the world, but those in Pennsylvania sought especially to convert Native Americans, which led to tensions between Moravians and other white settlers. Important Moravian missionaries included Johann Pyrlaeus (1713-85), David Zeisberger (1721-1808), and John Heckewelder (1743-1823). Moravian missionaries had more success than most other Protestant missionaries due to a number of factors, including their efforts to become fluent in Native American languages, their respect for Indian cultures, and their emphasis on the love of God. In evaluating potential converts, they looked more for a sense of sin and unworthiness, a love of God, and moral living rather than doctrinal precision. Moravian missionaries worked among the Mahican and Delaware Indians north of Philadelphia and in the Susquehanna Valley. They also sent missionaries to multiethnic towns, including Shamokin. In 1746, the Moravians founded a mission town called Gnadenhütten, some thirty miles from Bethlehem. By 1753, it was home to about 125 Delawares and Mahicans.

In the 1760s, however, the Moravian missions to the Indians foundered in the face of increasing hostility in the backcountry between whites and Indians. In 1763, the Delaware leader Teedyuscung (1700-63), who had once lived at Gnadenhütten, was murdered by unknown assailants. Later in the year, several Moravian Indians were killed, and this event (and others like it) set off a cycle of revenge killing among Indians and whites from Pennsylvania to Virginia. By November 1763, the colonial government feared that the Paxton Boys, vigilantes hostile toward both the Indians and the Moravians, intended to massacre backcountry Indians. The government demanded that Indians living at Bethlehem, Nazareth, and elsewhere report to Philadelphia. The Indians were imprisoned there, first on Province Island and then in disused army barracks for a year and a half. Even Moravian Indians who were full members of the Bethlehem community were forced to move. The Indians suffered from hunger and disease during their imprisonment, and by the time they were freed (in March 1765), fifty-six of the approximately 140 captives had died. After leaving Philadelphia, the survivors were not permitted to return to their homes. They were resettled near Wyalusing, in the northeast corner of Pennsylvania, where they established a town called Friedenshütten. This community, however, was short-lived, as the inhabitants were forced to move west in the 1780s under the twin threat of white and Iroquois expansion.

Complications of Pacifism

During the American Revolution, Pennsylvania Moravians faced serious difficulties. As pacifists and largely apolitical, they believed Christians should submit to legitimate authority. This made them unpopular with their patriot neighbors, who already distrusted them because of the Moravians’ good relationship with local Indians. During the war, the government of Pennsylvania forced Moravians to pay taxes and fines for their refusal to serve in the military, and the patriots demanded supplies from them. The General Hospital of the American Army was located at Bethlehem from December 1776 to March 1777 and from September 1777 to June 1778. The Americans also stored military equipment there.

By the end of the 1700s, the Moravians had lost much of their former distinctiveness. Due to debt and economic difficulties, they abandoned their communal economy at Bethlehem in 1762 and after the American Revolution grew to resemble other German Christian groups. In Philadelphia, the original congregation, located near Bread and Race Streets, began performing all services in English in 1817. (Previously, services had been held both in German and English.) In 1856, the congregation moved to a new church at Wood and Franklin Streets.

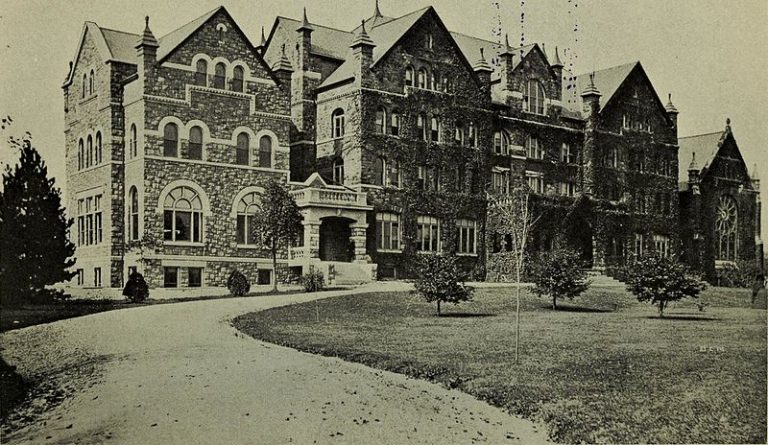

In Pennsylvania, Bethlehem remained the center of Moravian life. Nineteenth-century Moravians, like their predecessors, continued to sponsor missionary work, with missionary societies founded in 1818, 1840, and 1849. They also focused on education. The Moravians founded separate schools for boys and girls in the eighteenth century, and these gradually developed into the Moravian College and Theological Seminary (founded in Nazareth in 1807, relocated to Bethlehem in 1858) and the Bethlehem Female Seminary (1863). The men’s and women’s institutions merged in 1954 to form Moravian College.

Bethlehem’s Accessibility Grows

Nineteenth-century Moravians were also touched by events in the outside world. Economic change and the development of industry brought canals and railroads to Bethlehem, strengthening its ties to the outside world and leading to greater Americanization. In the case of warfare, for example, early Moravians had been pacifists who resisted service in the American Revolution. At the outbreak of the War of 1812, Moravians hotly debated the question of military service, but the Elders’ Conference ruled that a man who voluntarily joined the militia did not forfeit his membership in the church. During the Civil War, several students and two professors left the Moravian College and Theological Seminary to enlist.

In the twentieth century, the main developments of the church took place elsewhere, as the church expanded in the South, the Midwest, Canada, and overseas. As of 2018, the worldwide Moravian church was divided into twenty-four Provinces, nine of which were located in North America and the Caribbean. The Moravian church also evolved into a mainline Protestant denomination. Ecumenically-minded from the beginning, the Moravian church continued to teach that true Christians can be found in all denominations. In the twenty-first century, the church entered into full communion with the Evangelical Lutheran Church, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.), the Episcopal Church, and the United Methodist Church, in 2000, 2010, 2011 and 2018, respectively.

Bethlehem, which lies within the North American Northern Province, remained the home of Moravian College, a liberal arts institution, and Moravian Theological Seminary, an ecumenical seminary offering master’s degrees in Divinity, Theological Studies, Chaplaincy, and Clinical Counseling. As of 2007, Bethlehem had six Moravian churches, with an estimated total membership of about 3,300, and Moravian congregations also existed in Philadelphia and in Cinnaminson and Riverside, New Jersey.

Martha K. Robinson is an Associate Professor of History at Clarion University of Pennsylvania. Her publications include “New Worlds, New Medicines: Indian Remedies and English Medicine in Early America,” Early American Studies 3 (Spring 2005): 94-110. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Moravian Church of North America

- Our History (Moravian College)

- Redeemer Moravian Church, Philadelphia

- A Brief History of Three Religious Communities: Ephrata Cloister, Bethlehem and Harmony (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Czech Moravian Folk Music (YouTube, July 30, 2018)

- History of the Moravian Church (YouTube, April 1, 2019)

- Memoirs of Three Moravian Women, 1770s-1880 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Records of Moravian Church, York, Pennsylvania: Soul-Register of the Members of the Congregation and Society and their Children in Yorktown in the Year, 1780 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- "Collecting Carolina" Moravian Pottery (PBS, February 20, 2014)